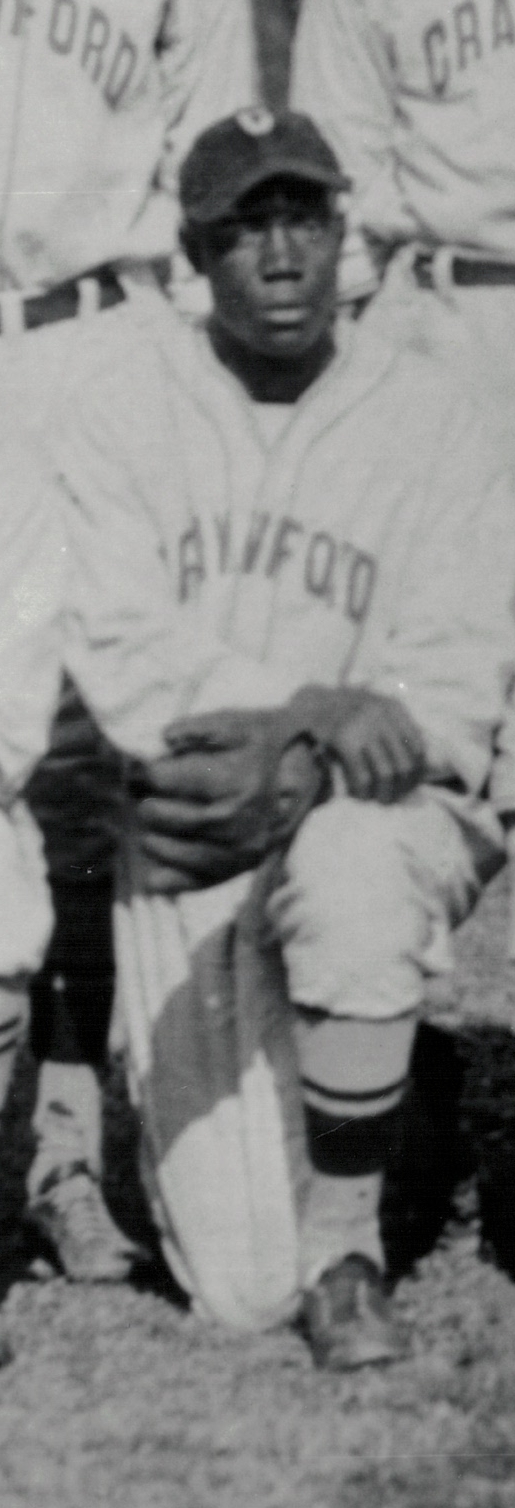

Chester Williams

Over the years, the Pittsburgh Courier, one of the nation’s leading African-American newspapers, used the following superlatives to describe Pittsburgh Crawfords infielder Chester Williams: Peppy, snappy, aggressive, hustling, scrappy, flashy. He was also referred to as sure-fielding, hard-hitting, a sparkplug, and even an inspired devil. From 1931 through the team’s demise in 1938, Williams was a fixture, mostly at shortstop, and an instrumental cog in the finely tuned machine that was the Crawfords. For good measure, Williams also spent time with Smoketown’s other Negro League powerhouse, the Homestead Grays, in 1932-33 and 1941-42.

Over the years, the Pittsburgh Courier, one of the nation’s leading African-American newspapers, used the following superlatives to describe Pittsburgh Crawfords infielder Chester Williams: Peppy, snappy, aggressive, hustling, scrappy, flashy. He was also referred to as sure-fielding, hard-hitting, a sparkplug, and even an inspired devil. From 1931 through the team’s demise in 1938, Williams was a fixture, mostly at shortstop, and an instrumental cog in the finely tuned machine that was the Crawfords. For good measure, Williams also spent time with Smoketown’s other Negro League powerhouse, the Homestead Grays, in 1932-33 and 1941-42.

Chester Arthur Williams was born on May 25, 1906, in Beaumont, Texas.1 The identity of his parents and how and where he spent his childhood remain shrouded in mystery, but it appears likely that Williams’s family must have moved to Lake Charles, Louisiana, when he was young and that he grew up there, since much of his life centered on that area.

Evidence of Williams appearing on a ball field pops up in 1929 with an independent team called the Shreveport Black Sports.2 He may have also played for the Houston Black Buffaloes before beginning his Negro League career with the Chicago American Giants in 1930.3 Williams played only a handful of games with the Giants before moving on to legendary manager and 32-year Negro League veteran Candy Jim Taylor’s Memphis Red Sox. There, Williams showed that he belonged. In statistics found from 63 games in 1930, Williams batted .297 in 219 recorded at-bats. He followed Taylor to the Indianapolis ABCs for the 1931 season before finally settling in with Gus Greenlee’s Pittsburgh Crawford Giants later in the year.

Pittsburgh racketeer, promoter, and baseball man Gus Greenlee’s dream was to field a championship baseball team, and he began this quest in earnest in 1931. Williams was one of the first players he signed, along with Sam “Lefty” Streeter, Pistol Johnny Russell, Jimmie Crutchfield, and Bill Perkins. A late-season acquisition of Satchel Paige from the failing Cleveland Cubs for a paltry $250 had Greenlee’s team headed in the right direction.4 Interestingly, at one point during the 1931 season, Chester joined an all-Williams infield, playing alongside Bobby, Bucky, and Harry Williams.5

Cum Posey, the owner of the Homestead Grays, who also played in Pittsburgh, had an ongoing battle with Greenlee for local supremacy that resulted in many players moving back and forth between the Grays and the Crawfords.6 Williams spent part of 1932 with the Crawfords, hitting .296 in limited action, but the bulk of his season had him as a member of the Homestead Grays. An early-season matchup against the New York Black Yankees shows the Grays’ shortstop rapping out three hits, including a double and a triple, in a 2-1 victory. In another contest, played in late September, Williams managed four hits while leading off in the Grays’ 10-0 drubbing of the Fort Wayne All-Stars.7

Williams started the 1933 campaign with the Homestead Grays and, in a May 25 matchup against the Pittsburgh Crawfords, he expressed his dissatisfaction with the way they had transferred him to the Grays the previous season. The Pittsburgh Courier’s John L. Clark wrote of Williams’s desire for revenge: “Chester has already served notice that the Decoration Day series, or any series with the Crawfords, for that matter, will find him at his best. That is saying something for the Texas star can play when he wants to.”8 Ironically, Williams found himself back with the Crawfords again by mid-July, but this time he stayed for a while, remaining a Crawford through the 1938 season.9

The 1933 Crawfords won a disputed Negro National League championship when Greenlee, president of the league at the time, declared them champs after the league failed to finish the second half of the season. The Chicago American Giants, winners of the first half, also laid claim to the title.10 After adding four future Hall of Famers – Josh Gibson, Oscar Charleston, Cool Papa Bell, and Judy Johnson – to go along with returning members Satchel Paige, and the slick-fielding Williams, the Crawfords had built the foundation of one of the greatest teams in baseball history.

The 1934 season was a good one for the Crawfords. They finished 52-29-3, but they were unable to win either the first or second half of the season and thus were left out of the championship series. Williams had a stellar season as the starting shortstop, stroking .321 with 75 hits in 234 discovered at-bats. He played so well that he was voted to his first of four consecutive East-West All-Star Games.

Sportswriter Nat Trammell wrote of Williams and his exceptional fielding ability after a 1934 contest against the Philadelphia Stars:

“Williams turned in several beautiful fielding plays. He dived on his eyebrows to stop (Biz) Mackey’s hit going across second base. Williams then somersaulted and threw perfect to (Leroy) Morney to force (Jud) Wilson at second and rob Mackey of a sure single, Williams again electrified the fans when he went back of (Oscar) Charleston to spear Chaney White’s drive and tossed him out at first as well.”11

The East-West All-Star Game was an extremely popular contest, first played the previous year, and its players were voted on by the fans and readers of the nation’s leading African-American newspapers. Williams’s first game was also his best as he smacked three hits and earned the batting honors of the day.12

Play-by-play announcer Lester Roberts described Williams’s big day:

“Back to the action I now return you, with one out on the East and one player who stands at first base, Chester Williams, who hit a single that jumped past Mule Suttles’ mitt.13

“Now Chester Williams is up next to face Foster and he singles just past first base on the first pitch, leaving no base free.”14

“… but that still leaves Williams holding the bat in the box with a count of two and two because that last pitch came in straight and true to serve up a strike, but now Foster sends a changeup to Williams as he swings on and bends past second base into shallow left field, putting Williams on base, and folks, he has a feel for the bat today because now he has three hits in the game from swinging so free.15

“… the next pitch from Satch is one Parnell likes as he swings and shoots a groundball to Chester Williams at second, who flashes the leather by making the catch with a backhand grab to his right, then turns to make the tag on Suttles off base, but Williams isn’t done – he spins and throws to first, and Charleston stretches to beat Parnell on the run. A great double play for outs two and three from Williams, who made it look so easy, ends the inning and ends the game, meaning today the East will be named champions of this East-West Classic in a game that was indeed a classic.”16

Although Williams excelled on the field, he was known to spend his spare time with heavy drinkers, like Josh Gibson and Sam Bankhead, and would often find himself in off-the-field trouble.17 He and catcher Curtis Harris were both suspended at one point during the 1934 season for “conduct unbecoming ball players and gentlemen,” tainting what was otherwise a stellar season for Chester Williams.18

Williams joined teammates Cool Papa Bell and Satchel Paige in the integrated California Winter League for its 1934-1935 season, playing for Tom Wilson’s Elite Giants. The Giants dismantled the competition with a 34-5-1 record. Williams got into seven games at second base and shined with a .483 average. He played sporadically in the league, but seemed to enjoy some success, last playing in the 1942-1943 season for the Royal Giants.19

The 1935 Pittsburgh Crawfords were a legendary team, sometimes compared to the 1927 New York Yankees, and finished the season 51-26-3, winning the NNL Championship Series in a nailbiter, four games to three over the New York Cubans. While Williams slumped to a .237 average during the regular season, he managed to come through when it most mattered in the final series. Williams pounded out three hits in the final game, two doubles and a triple, to help lead the Craws to an 8-7 Series-clinching victory.20

In 1936 Williams was voted to his third straight East-West All-Star Game, narrowly beating out future Hall of Famer Willie Wells for the starting nod at shortstop. Although he went 0-for-4 in the game, he did manage an RBI in his team’s 10-2 walloping of the West.21 Pittsburgh Courier city editor William G. Nunn praised Williams after the matchup: “We saw speed, dash and class. Oodles of it. We know that Chester Williams as he performed today is better than several major league shortstops.”22

The 1936 Crawfords were once again crowned champions of the NNL, winning the first half of the season and having a far superior record than the second-half winner, the Washington Elite Giants, but no championship series was scheduled. Instead, a team of all-stars, including Crawford teammates Josh Gibson, Cool Papa Bell, Satchel Paige, Sam Streeter, and Chester Williams, played in the prestigious Denver Post Tournament. The All-Stars swept the seven-game competition and took home the $5,000 prize.23

The year 1937 began with Gus Greenlee proclaiming to the Chicago Defender that Williams “will be the nation’s outstanding shortstop this season” and that he “wouldn’t trade Chester for any two infielders in baseball.”24 But Williams and the Crawfords disappointed that season, mostly due to the trades of Gibson and Judy Johnson and the movement of players to the Dominican Republic. Players like Satchel Paige and Cool Papa Bell, fed up with low salaries and poor conditions, were happy to travel south of the border in search of much larger paychecks. Williams spent the bulk of the season with the Crawfords but eventually took $1,000 to head south and play for dictator Rafael Trujillo’s all-star team in the Dominican Republic.25 Under extreme conditions and the threat of bodily harm, Ciudad Trujillo took the championship game and helped the dictator gain re-election. Williams played second base and chipped in with two RBIs in the final game.26 Meanwhile, back home, the Crawfords finished dead last in the six-team Negro National League.

Once the defectors had returned stateside, Williams suited up for an exhibition game against a team called the Dominican Stars, made up mostly of the Trujillo team, which included Bell, Paige, and Sam Bankhead. On September 23 at the Polo Grounds in New York, young New York Cubans pitcher Johnny Taylor led the Negro National League All-Stars against Paige and his Dominican Stars. Taylor pitched the game of his life, hurling a no-hitter and defeating Paige, 2-0. Chester Williams received much of the credit in helping limit the Stars to no hits. Pittsburgh Courier writer John Clark described his sparkling play: “Chester Williams, brilliant sparkplug of the Pittsburgh Crawfords, was the shining star in the finest and sweetest fielding combinations ever to show in the Big City. Working with Hughes at second, the pair guarded and patrolled the infield like Texas Rangers rounding up horse thieves. Not a single pellet got past them.”27

Always a popular player, Williams played in his fourth and final East-West All-Star Game in 1937 with the third most votes overall.28 Strangely, he led all shortstops in voting in 1938 and came in second to Willie Wells in 1939 but not play in either game. He also showed up in the voting in 1941, but once again did not play.29

Unlike his teammates Bell and Paige, Williams returned to the Crawfords for the 1938 season to witness the end of the once-mighty franchise. Williams had a fine season, hitting .308, but his team finished in the middle of the pack. After two consecutive poor seasons, owner Gus Greenlee sold the team after the 1938 season and new owner Hank Rigney move the Crawfords to Toledo, Ohio.30

It is unknown when Williams and his wife, Nellie Laffnette, were married, but they welcomed their first child, Deloris Jean, into the world on June 8, 1938.31 Deloris was followed by a second daughter, Chester Lee; a son, Leonard, who was born in March of 1943; daughter Patsy; and son Leroy Williams, who was named after Leroy “Satchel” Paige.32

Williams latched on with Philadelphia in 1939, hitting second and playing shortstop for the underachieving Stars.33 He had been expected to join Oscar Charleston and the Crawfords in their move to Toledo, but instead decided to jump ship.34 The 1939 season marked Williams’s last productive Negro League campaign as he batted .338 for the Stars.

His time with Philadelphia was short-lived, and Williams spent the rest of 1939 through much of 1941 splitting his time between Cuba and Mexico. His two winter seasons in Cuba were almost identical. He hit .298 in 188 at-bats for Santa Clara in 1939-40 and .299 in 174 at-bats for Cienfuegos in the winter of 1940-41.35 Williams also packed his glove and headed to Mexico to play for the 1940 Torreon team, for whom he tore the cover off the ball by cracking 107 hits in 311 at-bats for a .344 average. In his only foray into managing, Williams also skippered the 1940 Torreon team and led the club to a 45-41 record and a fifth-place finish. Hall of Famers Cool Papa Bell and Hilton Smith also played for Torreon that year. Williams returned to Torreon the following season, but he hit only .254 in 71 at-bats over 16 games.36

Hall of Fame third baseman Judy Johnson called Williams “a real holler guy” and Williams was known as a free spirit and someone who could get riled up easily. Two stories from his last two seasons in the Negro Leagues, when he again played for the Homestead Grays, show this side of him.37 Just before the 1942 Negro World Series between the Grays and the Kansas City Monarchs, Satchel Paige told Williams, then playing shortstop for the Grays, that Monarchs owner J.L. Wilkinson would give all the profits from the Series to his players. Williams knew that Grays owner Cum Posey would never match this offer, and Paige had managed to upset Williams and get in every Grays player’s head. Buck O’Neil commented, “These guys, they were stirred up. They were only getting a percentage of the money. That upset them. We had more to play for than they had to play for.”38 The Grays were swept in the Series, with Satchel Paige pitching in all four games for the victorious Monarchs.

A more humorous story was told by Memphis Red Sox lefty Verdell Mathis:

“I remember one time in Allentown, Pennsylvania, we were playing the Washington Homestead Grays – Josh Gibson, Buck Leonard, and those guys. They had a shortstop, a good one, named Chester Williams. He said, ‘Come on in here, we’re gonna run you to death.’ I wasn’t supposed to pitch that day, but Chester Williams kept ‘woofin’,’ you know, kidding you, trying to get a rise out of you. I didn’t like that. I didn’t like no team to start woofin’ about they were gonna do this or that. So our pitcher was warming up, and Chester Williams kept beefing and going on, so I got up off the bench, said, ‘Give me that ball.’ I went and took the ball away from Evans and warmed up four or five pitches. They got one run off me, and that was a home run Buck Leonard hit in the first inning. I wasn’t quite warm. But by the bottom of the ninth, when the game was over, we beat ’em 7-1. Chester Williams cried all the way to the dressing room. He said, ‘This just ain’t fair. How can you do this?’ I stopped him from woofin’, though.39

After Chester Williams finished his Negro League career with two lackluster seasons for the powerhouse 1941 and 1942 Homestead Grays, he had a lifetime batting average of .285 and was compared favorably to New York Yankees shortstop Mark Koenig of Murderers’ Row fame.40 In 14 games against teams made up of white major leaguers, Williams had 17 hits in 52 at-bats for a .327 average.41

Chester Williams returned home to Lake Charles, Louisiana, after his playing days were through and was drafted into the Army on October 9, 1943. He was honorably discharged on August 8, 1944, after hurting his arm.42 At the age of 46, Williams was shot and killed in a scuffle at his own establishment, the Cotton Club, in Lake Charles on Christmas day in 1952. According to news accounts of the incident, Williams was shot five times with a .25-caliber pistol and died almost instantly from his wounds.43 The man who shot him, Tom Scott, was taken to the hospital with ice-pick wounds inflicted by Williams in their scuffle. News accounts failed to report the further disposition of the case.44 Williams was buried with a military headstone at Hi-Mount Cemetery in Lake Charles.45

The 5-foot-9, 180-pound, speedy, sure-handed dynamo certainly deserved a chance to play in the major leagues, but his career was over before the integration of the game began. It is certain that much of the storied Pittsburgh Crawfords’ success from 1932 to 1936 can be attributed to Williams’ presence in the middle of the team’s infield.

Acknowledgments

Frederick C. Bush, co-editor of this book, spoke briefly with Mrs. Chester Lee Moses, Chester Williams’s second-born daughter, by phone on February 1, 2020, and then made contact with her daughter, Monique Jeffers. Bush’s conversation with Mrs. Moses was brief, though a few family details now included in this biography emerged, because she was scheduled to visit her daughter in March and planned to bring additional information and photographs to be given to Bush at that time. As readers assuredly know, this turned out to be the time when the worldwide COVID-19 pandemic began to hit the United States full force. Bush was unsuccessful in making further contact during that time, and both this author and the editors fervently hope that Chester Lee Moses and Monique Jeffers fared well through the ordeal. We hope to reconnect with them to obtain additional information that would expand this biography for future printings of this book and/or the SABR Biography Project website.

Sources

Unless otherwise noted, all statistics were taken from seamheads.com or baseballreference.com.

Notes

1 Ancestry.com, US Headstone Applications for Military Veterans, 1925-1963. Chester Lee Moses, Williams’s second daughter, confirmed that Williams was born in Beaumont, Texas, during a phone conversation with co-editor Frederick C. Bush on February 1, 2020.

2 Larry Lester and Wayne Stivers, The Negro Leagues Book, Volume 2: The Players, 1862-1960 (Raytown, Missouri: NoirTech Research Inc., 2020), loc. 6926.

3 Ryan Whirty, “Lake Charles Link to Negro League History,” American Press (Lake Charles, Louisiana), August 2, 2013. https://facebook.com/notes/negro-leagues-baseball-museum/lake-charles-link-to-negro-leagues-history/10151780555945236/.

4 Jim Bankes, The Pittsburgh Crawfords (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company Inc., 2001), 21.

5 Baseballreference.com. baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Chester_Williams.

6 Bankes, 16.

7 Pittsburgh Courier, May 7, 1932: 15, and October 1, 1932: 14.

8 Pittsburgh Courier, May 27, 1933: 7.

9 Pittsburgh Courier, July 15, 1933: 14.

10 James A. Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers Inc., 1994), 629.

11 Phil Dixon and Patrick J. Hannigan, The Negro Baseball Leagues: A Photographic History (Mattituck, New York: Amereon House, 1992), 236.

12 Pittsburgh Courier, September 8, 1934. 15.

13 Chester R. Smith Jr., Stars in the Shadows: The Negro League All-Star Game of 1934 (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2012) 59.

14 Smith, 14.

15 Smith, 15.

16 Smith, 16.

17 William Brashler, Josh Gibson: A Life in the Negro Leagues (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2000), 68. See also Riley, 847.

18 Whirty.

19 William F. McNeil, The California Winter Leagues (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company Inc., 2002), 171.

20 John Holway, The Complete Book of Baseball’s Negro Leagues: The Other Half of Baseball History (Fern Park, Florida: Hastings House Publishers, 2001), 321.

21 Larry Lester, Black Baseball’s National Showcase: The East-West All-Star Game, 1933-1953 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2001), 91-93.

22 Lester, 89.

23 Lester, 82-83.

24 Chicago Defender, April 10, 1937: 13.

25 Lester, 97.

26 Averell “Ace” Smith, The Pitcher and the Dictator (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2018), 114-115.

27 Pittsburgh Courier, September 25, 1937: 17.

28 Lester, 106.

29 Lester, 119, 139, 171.

30 Riley, 629.

31 Ancestry.com, US Social Security Applications and Claims Index, 1936-2007. Chester Lee Moses confirmed that her mother’s maiden name was spelled Laffnette rather than any of the variations, such as Lafaynette, found in some census records.

32 Pittsburgh Courier, March 20, 1943: 9, mentioned Leonard’s birth, though it did not provide his name. Chester Lee Moses provided the names and birth order of all of Chester and Nellie (Laffnette) Williams’s children.

33 Riley, 847.

34 Pittsburgh Courier, April 22, 1939: 17.

35 Jorge S. Figueredo, Who’s Who in Cuban Baseball: 1878-1961 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company Inc., 2003), 385.

36 Pedro Treto Cisneros, The Mexican League: Comprehensive Player Statistics, 1937-2001 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company Inc., 2002), 279.

37 Bankes, 68.

38 Brad Snyder, Beyond the Shadow of the Senators: The Untold Story of the Homestead Grays and the Integration of Baseball (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2003), 143.

39 John B. Holway, Black Diamonds: Life in the Negro Leagues from the Men Who Lived It (New York: Stadium Books, 1991), 149-150.

40 Bankes, 151.

41 Todd Peterson, The Negro Leagues Were Major Leagues: Historians Reappraise Black Baseball (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company Inc., 2020), 242. Seamheads.com says that in six games against teams made up of white major leaguers, Williams had 5 hits in 17 at-bats for a .294 average.

42 Whirty.

43 “Five Pistol Shots Fatal to Negro,” Beaumont Journal, December 26, 1952: 5.

44 “Ex-Baseball Great Slain,” Pittsburgh Courier, January 10, 1953: 14.

45 Whirty.

Full Name

Chester Arthur Williams

Born

May 25, 1906 at Beaumont, TX (US)

Died

December 25, 1952 at Lake Charles, LA (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.