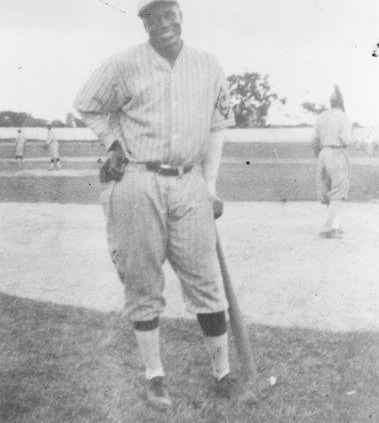

Chaney White

Outfielder Chaney White had a 17-year career in the Negro major leagues from 1920 through 1936. During that time, he was a member of numerous championship teams that included squads in various Negro Leagues, the Cuban Winter League, the Florida Hotel League, and the California Winter League. In 1934, at age 40, he was still a major contributor to his last championship squad, the Philadelphia Stars of the Negro National League II. Chaney, whom a World War I draft registrar described as “tall” and “stout” – he was listed as 5-feet-10 and 196 pounds during his playing days – compiled Negro League career totals that included a .312 batting average, a .375 on-base percentage, and 1,057 hits in 887 games against league or top-caliber independent opponents. Additionally, he batted .347 in three seasons in Cuba1 and .316 in two seasons in the California Winter League.2 His accomplishments were more than enough for him to make it onto the preliminary ballot of the National Baseball Hall of Fame’s 2006 Special Committee on the Negro Leagues, although he was not selected for enshrinement.

Outfielder Chaney White had a 17-year career in the Negro major leagues from 1920 through 1936. During that time, he was a member of numerous championship teams that included squads in various Negro Leagues, the Cuban Winter League, the Florida Hotel League, and the California Winter League. In 1934, at age 40, he was still a major contributor to his last championship squad, the Philadelphia Stars of the Negro National League II. Chaney, whom a World War I draft registrar described as “tall” and “stout” – he was listed as 5-feet-10 and 196 pounds during his playing days – compiled Negro League career totals that included a .312 batting average, a .375 on-base percentage, and 1,057 hits in 887 games against league or top-caliber independent opponents. Additionally, he batted .347 in three seasons in Cuba1 and .316 in two seasons in the California Winter League.2 His accomplishments were more than enough for him to make it onto the preliminary ballot of the National Baseball Hall of Fame’s 2006 Special Committee on the Negro Leagues, although he was not selected for enshrinement.

Chaney Leonard White was born on April 15, 1894, in Longview, Texas, the ninth of Alfred and Minda White’s 11 children.3 Alfred was a farm laborer while Minda tended to the home and children. At the time of the 1900 US Census, the White family was living in rural Kaufman County, Texas. By 1910 the family had moved to the town of Terrell, also in Kaufman County, which is 98 miles west of Longview and 32 miles east of Dallas.

Kaufman County was an unlikely place for the family to settle as it was extremely inhospitable to African American residents. In fact, on July 16, 1892 – slightly less than two years before Chaney White’s birth – the White citizens of Elmo, six miles east of Terrell, adopted several resolutions “[w]ith a view of discouraging the immigration of negroes into the settlement and removing the obnoxious citizens of color already in the precinct.”4 One of the resolutions expressed the concern that “[n]egro immigrants are pouring in upon us with an increase of ratio, which, if not stopped, will result in ruin to our schools and society. …”5 Amid such virulent racism, it was only a matter of time before the White family moved to Dallas, a city with no less segregation but with a much larger Black community in which they could feel more at home. The 1920 Census shows that Alfred and Minda White, along with their youngest daughter, Lottie, and granddaughter, Beulah Evans, lived on Golden Gate Avenue in the Western Heights section of Dallas. However, after Alfred’s death, Minda moved back to Terrell, and the 1940 Census shows she was living there with her daughter Lizzie (White) Johnson.

As for Chaney, nothing is known about his youth or how he first came to play baseball. What is definite is that he was playing professionally by 1917 (and perhaps earlier) as his World War I draft registration card from that year lists his profession as “Ball player” and his employer as Enos Whittaker, owner of the Dallas Black Giants. The Dallas team was a member franchise of the Texas Colored League, and White was in fast company on the 1917 squad that included fellow future stars like Dave Brown, Jim Brown, and Oliver “Ghost” Marcell. White’s early career was interrupted when Uncle Sam came calling. He served in the US Army in World War I, and was discharged on August 9, 1919.

At the outset of the 1920 season, the Dallas Express, which had been “made the official organ of the Texas Colored League,” reported that “Johnson Hill and Chaney White, one fleet-footed out fielder [sic] are slated to be sold to Detroit.”6 White was not sold to Detroit, but, in an April 10 news article, was reported to be a member of the Fort Worth Black Panthers as that team prepared to face the Black Giants.7 The same article noted, “Lewis Lofton, better known as ‘San Top’ a former Texas Leaguer and ex-Royal Giant was in Dallas Monday. … This year San Top will be a member of the famous Hilldale Club of Philadelphia.”8

San Top was Fort Worth-born Louis Santop Loftin, a catcher who was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 2006, and he stayed around his hometown long enough to play the early months of the season with Chaney and the Black Panthers. The box score from the April 11 matchup between the Dallas and Fort Worth teams shows that White started in left field and batted leadoff (his speed garnered him the nickname Reindeer) and that he went 2-for-4 with a double, a triple, and three runs scored in a 13-3 triumph for Fort Worth. “Sand Top” [sic] was Fort Worth’s starting catcher and had a 2-for-3 day at the plate with a double and two runs scored.9

White made such a great impression on Santop that the catcher, who also served as a scout/recruiter for Hilldale, took him north to Philadelphia when he left Texas to rejoin Ed Bolden’s Hilldale Club.10 White’s widow, Helena, confirmed this sequence of events 20 years after his death, relating, “My husband told me that ‘Sandtop’ brought him to Philadelphia from Texas. Now, ‘Sandtop’ was one of the greatest Negro catchers that there ever was. I guess that was in about 1920 or 21. I’m not sure. That’s how my husband broke into baseball.”11 Since White had already been playing professionally, it is more accurate to state that his journey to the Northeast is how he set out on the road to stardom and a Hall of Fame-caliber career.

Santop and White joined Hilldale in July 1920, but White scuffled in his first season up North. There was no organized Negro League in the Northeast at that time, so Hilldale played against fellow top Black independent squads and faced off against many White semipro teams and even occasional White major-league aggregations. Although White fared well enough against the semipros,12 in 14 games against the top Black clubs, he batted only .160 (8-for-50) and had a .222 on-base percentage. In three games (all losses) against White major leaguers, he batted .091 (1-for-11). Hilldale had a 9-9-2 record against its fellow Eastern Independent clubs, while the Brooklyn Royal Giants (13-7-2) and Atlantic City Bacharach Giants (22-16-2) played superior ball. Hilldale played as far into the fall as possible, and, on October 16, defeated a semipro team from Upland, Pennsylvania, for what the Philadelphia Inquirer identified as “the championship of Delaware County.”13 White had two hits, stole two bases, and scored a run in Hilldale’s 3-2 triumph.

Both White and the Hilldale Club made dramatic improvements in 1921, so that the team could boast of more than a mere county championship. White became the team’s starting left fielder and in 40 games against top Black teams, he batted .300 for the first time as he rapped out 45 hits in 150 at-bats. Hilldale finished with a 28-18-1 record that gave the squad a .609 winning percentage. Hilldale’s closest competition, the Atlantic City Bacharach Giants, played a far greater number of games and compiled 16 more victories, but the team’s 44-36-2 mark resulted in only a .550 winning percentage. Thus, Hilldale claimed superiority over its six top competitors in the East for the season.

The 1922 season brought about different results, however. For one thing, there were four new top-caliber Black clubs in the East, a circumstance that caused a bidding war for available players. Apart from Phil Cockrell, Hilldale’s pitching staff was thin and posted an 85 ERA+, denoting that – as a staff – they were 15 percent below the average of all Eastern teams. White remained Hilldale’s starting left fielder, but his batting average dipped to .285, though he was still a productive player. His team’s record fell to 20-26-2 against the other Black independent clubs, and the Richmond Giants ruled with a 31-17-3 ledger.

At the season’s conclusion, Bolden called a meeting with several of his fellow team owners, and the group founded the Eastern Colored League that was to begin play in 1923. Now, the Eastern clubs truly had a championship to play for, and the new circuit also provided competition for Rube Foster’s Western loop, the Negro National League. In fact, from 1924 to 1927, the champions of the two leagues were to clash in the Negro World Series for supremacy over all Black baseball.

Prior to the 1923 season, Bolden cleaned house to assemble an improved squad that might make Hilldale the ECL’s first champion. He released several players who had filled only minor roles or whose performance had declined in 1922. White fell into the latter category and, though he had certainly not performed poorly, he found himself looking for new employment. He did not have to wait long for a new team to come calling, as the press soon reported that the Atlantic City Bacharach Giants, an ECL member franchise, had “grabbed Chaney White, the crack outfielder.”14 Both Hilldale and Atlantic City participated in two Negro World Series before the ECL’s demise during the 1928 season; however, only Hilldale, in 1925, emerged triumphant from Black baseball’s championship tilts between its Eastern and Western circuits.

The Bacharachs finished in fourth place in the ECL’s 1923 inaugural campaign, but White contributed the sterling defense for which he was known and a .304 batting average in 47 league games played. In 1924, when Atlantic City again finished fourth, White was batting .344 in 21 ECL games before he abruptly switched teams to the Washington Potomacs, another ECL member. The reason for White’s move is unknown; in fact, there is uncertainty as to whether he jumped teams or was released by Atlantic City because of a series of minor injuries he was reported to have suffered during the first half of the season.15 In any case, White manned center field and batted .288 in 19 games for the seventh-place Potomacs, which gave him a cumulative .318 batting average for the season. That year, White’s former team, Hilldale, lost the first Negro World Series, five games to four, to the NNL’s Kansas City Monarchs.

In 1925 the owner of the Potomacs, George Robinson, moved the franchise to Wilmington, Delaware, in the hope that his team would fare better financially. White moved from Washington to Wilmington with the club and from center to right field on the diamond. He smashed the ball to the tune of a .377 batting average in 32 games played, but the Potomacs fared miserably and finished 10-21-2 in a half-season. On July 23, with the franchise’s bottom line still bleeding red, it was announced, “George Robinson, sole owner of the Wilmington Potomacs, has quit. The Eastern officials have been notified by him that he is out of the game and that his players are now at liberty to sign with any other outfit.”16 Oddly, White was signed by his previous employer, the Atlantic City Bacharach Giants.

Back in New Jersey, White played 30 games in left field and batted .328 (for a .353 cumulative BA) for a Bacharachs team that finished in fourth place for the third consecutive year. Meanwhile, Hilldale became the first ECL team to be crowned king of Black baseball as it defeated the Monarchs, five games to one, in a rematch of the previous season’s Negro World Series. Soon, the Bacharachs were to take their shot at the title.

Dick Lundy took over Atlantic City’s managerial reins in 1926 and piloted a squad with an excellent pitching staff (117 ERA+), led by Rats Henderson and Claude Grier, to the ECL title.17 The Bacharachs faced the Chicago American Giants in a World Series that was to go to a maximum of nine games, if necessary, but 11 games were played as Games One and Four ended in ties. Grier threw a no-hitter in Game Three, a 10-0 drubbing of Chicago. After Atlantic City won Game Eight, 3-0, with White’s three-run triple providing the winning margin, the team had a four-games to two lead. The Baseball Fates, however, decreed that Chicago was to pull off a miracle, and the American Giants won the next three games to capture the Series. Future Hall of Famer Willie “Bill” Foster, Rube’s younger brother, stymied the Bacharachs in a tightly contested finale, 1-0. As for White, he had hit .283 in 56 games during the regular season; however, despite his Game Eight heroics, he batted only .231 in the World Series.

Lundy and his team were determined to defend their ECL title in 1927 and to have another shot at a Negro World Series championship. The ECL had adopted the split-season format for the first time, which created the possibility that there might be a league championship series to play to determine the loop’s World Series representative. The Bacharachs avoided such a scenario by winning both halves of the season. In fact, the squad overcame all obstacles thrown its way, including financial instability – the team’s parent corporation entered bankruptcy proceedings in April – and being temporarily thrown out of its home venue, Bacharach Park, in mid-June.18

White patrolled center field and batted .328 with a .398 on-base percentage while leading the ECL in hits (115), runs scored (79), and games played (89). Lundy, Oliver Marcell, and Clarence Smith also hit over .300 to pace Atlantic City’s offensive attack, and the pitching staff, led now by Luther “Red” Farrell, alongside Henderson and Jesse “Mountain” Hubbard, was as strong as the previous year (107 ERA+). The Bacharachs breezed to a return engagement against the same foe, the Chicago American Giants, in the World Series.

This time around, Chicago took a commanding lead by capturing the first four games, none of which was even close; the American Giants won 6-2, 11-1, 7-0, and 9-1. Amazingly, an Atlantic City pitcher again hurled a no-hitter, but this time it gave the team only its first triumph in the Series. Farrell tossed seven no-hit innings in Game Five, although five walks and four errors resulted in a slim 3-2 victory; the game was shortened by nightfall but it nonetheless counted as a win and gave the Bacharachs continued life. A Bacharachs pitcher throwing a no-hitter was not the only event that harkened back to the 1926 Series. After Game Six ended in a tie, Atlantic City won the next two games to make it a 4-3 series; however, Willie Foster again prevailed for Chicago in Game Nine and handed Atlantic City its second consecutive World Series loss. White struggled mightily against Chicago’s pitching staff and batted only .152 in the Series.

Despite White’s postseason struggles, he was now hitting his stride as a star player. First, he played for the Royal Poinciana squad in the Florida Hotel League. (He had been a member of the Breakers team in 1925.) Then he participated in his first winter league outside of the United States as he ventured to Cuba, where he joined the Almendares team during the 1927-28 winter season. White led his team with a .363 batting average, but it did not prevent the squad from finishing last. Things got so bad that “[w]hen Habana devastated Almendares 18 to 4 on January 21, the Blues withdrew from the league in shame and the season was terminated after one last victory of the [Habana] Reds over Cuba.”19

White returned to Atlantic City for the 1928 season and continued his run of stellar center field defense and powerhouse hitting. His batting average climbed to .371 and led the team, and his .424 on-base percentage contributed to his leading the league in runs (54) for the second consecutive year. White’s performance had not gone unnoticed, and, in June, the Pittsburgh Courier extolled his abilities:

One can’t mention the great outfielders of all time and leave out the name of Chaney White. …

There is no team in the country which could not bench a man in order to make room for this Texas speedboy who has burned up the base paths and the back lawn grass with his fleetness since he came North and East seven or eight years ago.

Observers rate him the peer of Oscar Charleston in the middle garden, and certainly he does everything as well as the Hoosier hustler. …20

Not only the press, but also White’s peers, had taken notice. His rare combination of size and speed led one opponent to declare that he was “built like King Kong but runs like Jesse Owens.”21 Added to that combination was a “hard-nosed approach” to the game that “earned him a reputation as a ‘dirty’ ballplayer, and he made no distinction about who was on the receiving end of his flashing spikes.”22 His rough and rugged personality on the diamond “contrasted with his demeanor off the field, where he was quiet and slow-talking, with a girlish laugh … and was described as a gentleman and a scholar.”23

As big a star as White had become, neither he nor his teammates could do anything more to solve the Bacharachs’ financial dilemma other than to play their best baseball. Finances were an issue for every ECL team, and the league disbanded in June. White remained with the Bacharachs, which played out the season as an independent club.

In the winter, White returned to Cuba and played for Cienfuegos. Although he was part of a different team, it was a season of déjà vu. White hit the cover off the ball at a .394 clip, but Cienfuegos and Cuba withdrew from the league after Almendares had taken a 10½-game lead in the standings. Cienfuegos finished in last place.24

The 1929 season marked White’s last year with Atlantic City. The franchise folded after the season. The Bacharachs were now members of the new American Negro League, which included five teams from the ECL along with the Homestead Grays; the ill-fated league also disbanded at the conclusion of its only season. Once again White played outstanding ball and batted .346, but the Bacharachs went backward and finished in fifth place ahead of only the Cuban Stars East team. White summarized the Bacharachs’ struggles that year succinctly, when he explained, “When we’re hitting the pitchers are going bad. When the pitchers [sic] settin’ ’em down we’re not hitting.”25

In September White played a few games for Hilldale and then joined Danny McClellan’s All-Stars for a brief tour of exhibition games; the only available box scores show him with a 4-for-7 batting line for a .571 average in two games. Next, he traveled south for his last round of winter ball in Florida. White was the hero of the championship game “when his base hit drove in … the winning run and captured the ‘league’ title for the Royal Poinciana squad.”26 Afterward, he went to Cuba, where he again played for Cienfuegos, for what also became his last winter season on the island. Cienfuegos’ fortunes were completely reversed, and, while White batted a more modest .310, the team captured the championship by 6½ games over second-place Santa Clara.27

Upon his return stateside, White briefly roamed the outfield for the Homestead Grays28 before he once again joined the Hilldale Club in May. Hilldale played as an independent team in 1930 and struggled mightily. In spite of talent including White and catcher Biz Mackey, and a pitching staff that included Cockrell, Hubbard, and Webster McDonald, the team managed only an 8-30-1 record.

Like the Potomacs and the Bacharachs before, the Hilldale franchise experienced serious financial problems in 1930, and White left the team in July to rejoin the Homestead Grays, for whom he batted .348 in 45 games as the team finished 45-15-1, the best record of all the Eastern Independent Clubs. In the season’s most notable game, White smashed a 12th-inning, game-winning RBI double against the Kansas City Monarchs at Muehlebach Field on August 1 to end a remarkable pitchers’ duel. The Monarchs’ Chet Brewer went the distance and struck out 19 Grays batters, but Homestead’s starting pitcher, Smokey Joe Williams, outdid him by fanning 27 Monarchs as he completed the shutout.29

When the time for winter league play arrived, White headed west to California – rather than returning to Cuba – to play in what was the only integrated league in the United States at that time. The 1930-31 winter season in the Golden State was an unusual one as “there were two competing integrated winter leagues, the ‘official’ California Winter League, whose Negro league entry played out of White Sox Park, and whose primary competition was Pirrone’s All-Stars, and the ‘other’ Winter League, whose Negro league team played out of Wrigley Field.”30 White was a member of the Philadelphia Royal Giants that played at Wrigley Field, where they dominated the competition. Statistics for the league are incomplete, but available information shows that White played center field and batted .328 in 16 games for the Royal Giants while the team compiled a 28-2-1 record.31

In 1931 John Drew took over the ownership of the Hilldale Club, and he signed many of the team’s former stars, including White, to try to resurrect the once great and proud franchise. The team again played an independent schedule but performed much better than it had in 1930, finishing with the best record of the Eastern Independents at 38-14-1. Mackey led the squad in hitting with a .362 batting average while White slumped a bit to .296, fifth among the team’s starting batters. At the end of the year, White headed West to play his last season of winter league ball in California. The league was back to normal – only one circuit consisting of four teams – and White and the Philadelphia Royal Giants again dominated the competition. Available articles and box scores show that White batted .294 in seven games while the Royal Giants won 20 games and lost only 2.32

The following season, Hilldale joined the new East-West League that was formed by Grays owner Cumberland Posey. The league consisted of eight full-fledged member franchises and two associate members, but it was doomed to financial failure from the outset. On March 31 Drew announced that he was “slashing the team budget to $2,200 per month,” which spurred immediate player defections by numerous stars, including Mackey, Rap Dixon, and Martín Dihigo.33 Player-manager Judy Johnson defected to the Pittsburgh Crawfords in June, adding another nail to the team’s coffin. White made his move in July when he signed with the Baltimore Black Sox, which finished in first place in the EWL’s brief season. White had hit only .257 in 29 games with Hilldale, but he was rejuvenated in Baltimore and improved to .358 in 15 games with the Black Sox to give him a cumulative .292 batting average for the season.

In 1933 Ed Bolden formed a new team called the Philadelphia Stars and, unsurprisingly, filled the squad’s roster with many of his former Hilldale players, including White. The Stars played as an independent team that year and finished with a 22-13 record against other top Black clubs in the East. At 39 years old, White still started in left field but batted only .265 in 28 games.

The Stars gained admission to the Negro National League II in 1934. The new league also had been founded the previous year after a one-year gap since Rube Foster’s first NNL had folded at the conclusion of the 1931 season. Now entering his 40s, White showed he still had one last burst of energy left in his baseball tank. He played in 67 NNL2 games in which he batted .302, led the team in runs scored (52), and was second in hits (77) to Jud Wilson; Wilson was the only other starter to bat over .300 (.358) and had 78 hits. Outside of White and Wilson, the Stars were no offensive juggernaut, so they relied on their stellar pitching staff. Philadelphia’s primary starters for league games – Slim Jones, Rocky Ellis, Webster McDonald, and Frank “Lefty” Holmes – all had seasons in which they were well above the league average in ERA+. The Stars were locked in a three-way battle with the Chicago American Giants and intrastate-rival Pittsburgh Crawfords for supremacy in the NNL2. Chicago claimed the league’s first-half title, but the Stars prevailed in the second half.

White and his new team, the Stars, now faced his old Bacharachs nemesis, the Chicago American Giants, in a playoff series to decide the NNL2 champion. On September 11, the two teams met for Game One at Passon Field in Philadelphia. Ellis started for the Stars and held a 3-2 lead when he gave way to Jones at the top of the ninth inning, but Jones surrendered two runs to hand the American Giants a 4-3 victory.34 Games Two and Three were part of a doubleheader at Cole’s Park in Chicago on September 16. Jones started Game Two but lost a tough 3-0 game to Chicago’s Ted Trent, who stymied the Stars with a four-hitter.35 Philadelphia salvaged the nightcap by a 5-3 score, but lost Game Four the next day by a 2-1 tally to find itself in a three-games-to-one hole.36

The series now moved back to Passon Field for the final three games. Ellis kept the Stars alive with a tough-as-nails 1-0 shutout in Game Five on September 27, and Paul Carter followed with a complete-game four-hitter in a 4-1 triumph on September 29 that knotted the series at three games apiece.37 Game Seven, on October 1, ended in a 4-4 tie when the game had to be called after nine innings because of darkness.38 The game was replayed the next day, and Jones not only “twirled the Ed Bolden crew to the loop diadem with his speedball and baffling cross-fire to turn in six strikeouts, but he also put the game on the proverbial ice when he blasted in the final run with a sharp single to left in the seventh.”39 He finished the championship clincher with a five-hit, 2-0 triumph. White, who had played a big role in helping the Stars to reach the championship series, played in only two of the games but batted .286 with a double and an RBI; he also stole a base, showing that he still had his speed as well as his bat.

White returned to the Stars in 1935, and the team was expected to contend for a second consecutive championship. An article in the Chicago Defender declared that the Stars’ pitching staff was “rated with the best in baseball.”40 Philadelphia’s offense was vastly improved, but the vaunted pitching staff’s ERA climbed from 2.61 in 1934 to 5.28 in 1935 and the team finished in fourth place in the NNL2 with 37-31-4 record. After one last hurrah in 1934, White again began to show signs of age as he batted .287 for the season in 55 league games; it was a respectable mark but placed him only sixth among the batters in Philadelphia’s starting lineup.

The Stars did not re-sign White for the 1936 season, but the New York Cubans, another NNL2 franchise, decided to see how much he had left to contribute. The Cubans used White primarily as a backup outfielder,41 and he batted .308 in 17 league games. Despite his production when given an opportunity, the Cubans released White in late July. He signed with the Brooklyn Royal Giants, where he again saw limited duty, and then retired quietly at the end of the season.42

At some point in the early 1940s – most likely in 194343 – White married Helena Louise Pringle and started a family in Philadelphia. White worked as a bartender while his wife raised the children and tended to their home. Their first son, Leonard, was born in 1944. Their second son, Darryl, died of pneumonia just 11 days after his birth in December 1947. Chaney and Helena overcame this tragedy and had two additional children, daughters Chanette and Beverly.44 Chaney White died of acute renal failure on February 23, 1967, and was buried at Mount Lawn Cemetery in Sharon Hill, Pennsylvania. Helena outlived Chaney by 38 years, and she became a Philadelphia institution herself as a health-care union activist.45

In a 1987 interview Helena gave about her husband, she showed both his gentlemanly side and how he had remained involved with baseball even though he had not been an active participant in any way. She related that “[h]e used to give the ballplayers, the younger fellows who came in to play with the Stars, a place to stay if they spent all their money. We had a large rooming house[,] so we used to keep them during the summer. If they’d spent their money, he would buy them a bus ticket so they could get back home.”46 She also noted that White “[w]as never bitter about only being able to play in the Negro Leagues, though. He was glad when Jackie Robinson broke in. He said that now the younger men would have a chance to do what they couldn’t do.”47

At the conclusion of her interview, Helena added about Chaney White, “My husband was a center fielder. Different people I’ve talked to said that he was one of the greatest that they had at the time. … They were just too late in giving the black ballplayers their share.”48 Considering White’s statistics, longevity, and championships won, perhaps he will yet have a share in the National Baseball Hall of Fame with his own plaque.

Photo credit

National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

Sources

Except where otherwise indicated, Negro League player statistics and team records were taken from Seamheads.com.

All Cuban Winter League player statistics and team records were taken from the two books by Jorge S. Figueredo that are cited in the Notes. In some instances, there are minor variations between Figueredo’s statistics and the CWL statistics found on Seamheads.com.

Ancestry.com was consulted for US Census information as well as birth, marriage, military, and death records.

McNary, Kyle, Black Baseball: A History of African-Americans & the National Game (New York: Sterling Publishing Co., Inc., 2003).

Revel, Dr. Layton. “Forgotten Heroes: Chaney White,” Center for Negro League Baseball Research, http://www.cnlbr.org/Portals/0/Hero/429409%20Chaney%20White%20Serie.pdf, accessed January 4, 2023. (Dr. Revel’s extensive research also includes statistics for as many exhibition games as he could locate in newspapers, which differentiates his career totals for White from the statistics found on Seamheads.com’s Negro League database that include only games against teams of Negro major-league caliber. This author has chosen to use the statistics from Seamheads since the quality of semipro teams and other exhibition opponents varied dramatically; however, it must be conceded that Dr. Revel’s findings give a more complete picture of White’s career statistics and especially highlight the great number of games he played beyond league contests.)

Notes

1 Jorge S. Figueredo, Who’s Who in Cuban Baseball, 1878-1961 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2003), 360-61.

2 William F. McNeil, The California Winter League: America’s First Integrated Professional Baseball League (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2002), 263.

3 Two items regarding White’s birth information and genealogy must be addressed. 1) White always cited 1894 as his birth year; however, his death certificate, for which his wife provided information, lists 1895; since White always provided 1894 and all other official records list the same, it appears to be the correct year. 2) As a child, White’s name was never listed as Chaney in any US Census but rather was given as some misspelled version (“Lenton” or “Lenard”) of his middle name Leonard – it is possible that his family called him by his middle name; as an adult, by the time of the 1950 Census, his name was rendered as “Chaney L White.” Considering the misspellings of his name and the inconsistencies about his birth year between the 1900 and 1910 Censuses (the latter of which still lists “Lenard” in proper birth order among the children in the house but gives the wildly incorrect birth year of 1909), White’s death certificate, which indicates that his mother had the uncommon first name Minda, was vital in determining that this author had discovered the correct White family; although her name was also misspelled as “Lindia” or “Menda” at times, in other instances it was correctly rendered as “Minda.”

4 “Color Line at Elmo/A Movement on Foot to Rid That Community of Worthless Negroes/Thrifty White Laborers Are Desired,” San Saba County (Texas) News, July 22, 1892: 2.

5 “Color Line at Elmo.”

6 J. Alba Austin, “Local Happenings/Everything Fit to Print,” Dallas Express, March 27, 1920: 9.

7 J.A. Austin, “Baseball,” Dallas Express, April 10, 1920: 11.

8 J.A. Austin, “Baseball.”

9 “Baseball,” Dallas Express, April 17, 1920: 3.

10 Santop also took pitcher Cornelius “Connie” Rector – another Black Panther and ex-Black Giant – along with White to join the Hilldale Club. For evidence of Rector’s play for both Fort Worth and Hilldale, see: J.A. Austin, “Baseball,” and Frank H. Ryan, “Hilldale Beats Paterson Stars in Great Finish,” Camden Courier-Post,” September 2, 1920: 19.

11 Renee V. Lucas, “Her Husband Was a Center Fielder in Negro League/Helena White, 67,” Philadelphia Daily News, February 3, 1987: 35. Seamheads.com shows that White played in 17 games for Hilldale in 1920; thus, Helena White was correct when she initially stated that 1920 was his first season in Philadelphia.

12 See, for instance: “Hilldale Colored Club Trounces Harlan, 11 to 3,” Wilmington (Delaware) Morning News, August 24, 1920: 8, and Frank H. Ryan, “Hilldale Beats Paterson Stars in Great Finish.”

13 “Hilldale Beats Upland Before 7000 Rooters,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 17, 1920: 22.

14 “Bushwicks in Double Header Sunday,” Brooklyn Standard Union, April 27, 1923: 19.

15 Dr. Layton Revel, “Forgotten Heroes: Chaney White,” Center for Negro League Baseball Research, http://www.cnlbr.org/Portals/0/Hero/429409%20Chaney%20White%20Serie.pdf, 14, accessed January 4, 2023.

16 “Wilmington Potomacs Throw Up the Sponge/Robinson Gives Up; Players Go,” Pittsburgh Courier, July 25, 1925: 13.

17 As of January 2023, Seamheads shows Hilldale with a 53-33-2 (.616) record and Atlantic City at 43-28-1 (.606), which would lead a person to believe that Hilldale should have been the ECL champion in 1926. An imbalanced schedule, poor reporting, and various other circumstances resulted in Atlantic City claiming the ECL title that year. For explanations about how the Bacharachs became the champion, see: James Overmyer, Black Ball and the Boardwalk: The Bacharach Giants of Atlantic City, 1916-1929 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2014), 144-46, and Revel, “Forgotten Heroes: Chaney White,” 17.

18 Overmyer, 161.

19 Jorge S. Figueredo, Cuban Baseball: A Statistical History, 1878-1960 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2003), 174-77.

20 “A Warrior Bold,” Pittsburgh Courier, June 23, 1928: 16.

21 James A. Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, Inc., 1994), 833-34.

22 Riley, 834.

23 Riley, 834.

24 Figueredo, Cuban Baseball, 177-81.

25 Overmyer, 182.

26 Revel, 38.

27 Figueredo, Cuban Baseball, 182-83.

28 “Grays Defeat Saints by 4 to 1 Margin,” Chicago Defender (National Edition), April 26, 1930: 9.

29 “Grays Win 1-0 as ‘Smokey Joe’ Fans 27 K.C. Players,” Chicago Defender (National Edition), August 9, 1930: 8.

30 McNeil, 143.

31 McNeil, 152-53.

32 McNeil, 156.

33 Revel, 30-31.

34 Christopher Hauser, The Negro Leagues Chronology: Events in Organized Black Baseball, 1920-1948 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2006), 84.

35 “Giants Lead Philly in World’s Series 3 to 1,” Chicago Defender, September 22, 1934: 16.

36 “Giants Lead Philly in World’s Series 3 to 1.”

37 “Phila. Stars Triumph,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 28, 1934: 22; “Stars Jolt Giants and Tie Up Series,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 30, 1934: 51.

38 Hauser, 85.

39 “Stars Upset Giants Win National Title/‘Slim’ Jones Hurls Phila. Negro Team to 2-0 Win Over Chicago Rival,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 3, 1934: 22.

40 “Plenty of Pitching Class Here,” Chicago Defender (National Edition), July 20, 1935: 15. The caption to a photo of the Stars’ pitching staff that was included here erroneously gave Holmes’s first name as “Sam.”

41 Revel, 36.

42 Revel, 37.

43 White appears still to have been single in 1942. He listed a friend as his contact person on his World War II draft registration card that year, and his first son, Leonard, was born in 1944; thus, 1943 makes sense as the year of his and Helena’s marriage (although the year remains uncertain).

44 Yvonne Latty, “Deaths: Helena Pringle-White, Ex-Union Activist,” Philadelphia Daily News, January 5, 2005: 22. The obituary states that Helena White was also survived by an adopted daughter, Clarice Pierce, but does not indicate whether Clarice was adopted by both Whites or by Helena alone after Chaney White was dead.

45 Latty.

46 Lucas.

47 Lucas.

48 Lucas.

Full Name

Chaney Leonard White

Born

April 15, 1894 at Longview, TX (USA)

Died

February 23, 1967 at Philadelphia, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.