Passon Field (Philadelphia, PA)

This article was written by Rebecca Alpert

The first half of the twentieth century featured the proliferation of amateur and professional sports teams, including baseball, softball, football, basketball, soccer, and hockey. Baseball, Black and White, was far and away the most popular, and flourished in the city of Philadelphia beginning in the mid-nineteenth century. Philadelphia was home to hundreds of baseball teams.1

Amateur, semipro, and professional games were played at several dozen ballparks and athletic fields throughout the city, mostly by men and boys but also by women.2 Some of the parks and fields were in the burgeoning neighborhood of West Philadelphia. Beginning at the turn of the last century, the population of West Philadelphia tripled in number as it became home to new immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe, primarily Italians and Jews. As part of the Great Migration, Southern Blacks also began to make “West Philly” their home during this time.3 Among these groups were many sports enthusiasts. One of those West Philadelphia spaces where they came to watch games was Passon Field, at 48th and Spruce Streets. It was there that the 1934 championship series between the Philadelphia Stars and the Chicago American Giants took place. The park was known as Passon Field from 1929 to 1942 but was called by many other names before and after.4

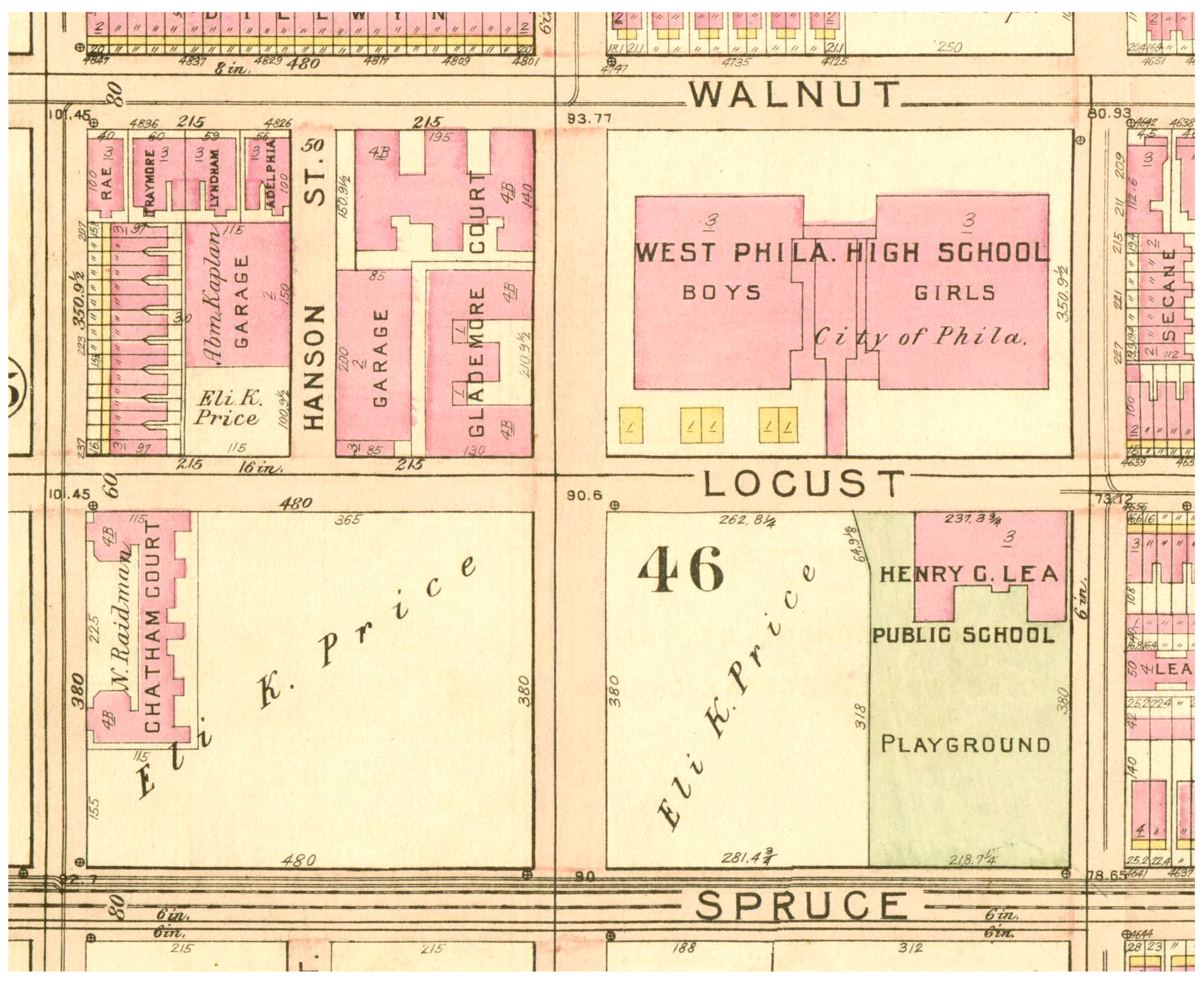

Beginning in 1923 the athletic field at the northwest corner of 48th and Spruce Streets received attention in the Black and White press. It was occasionally referred to as Lit Brothers Field or Elks Field, but most often it was just called the athletic field at 48th and Spruce, or simply 48th and Spruce and occasionally Spruce Field.5 The 1927 Bromley atlas of Philadelphia map of the block between Spruce and Locust and 48th and 49th Streets shows a small apartment complex, Chatham Court, at the corner of 49th and Locust. The rest of the block is an open space, with the name Eli K. Price printed across it.6

Price (1797-1884) was a Pennsylvania state senator and a prominent Philadelphia lawyer and civic leader. He purchased many parcels of land in West Philadelphia that were passed down through his estate.7 48th and Spruce was one of those properties, purchased in 1852. The estate maintained ownership until 1948, when Price’s great-grandchildren, as trustees, sold it to the City of Philadelphia’s Department of Recreation for use as a public playground and recreation center for $259,000.8 The property was used by the School District of Philadelphia starting in 1950 and it became the home field of West Philadelphia High School’s Speedboys football team, while it continued for many years to be used as a public playground and recreation center.9

The Philadelphia Inquirer first mentions the field in 1923, calling it the athletic field at 48th and Spruce, and describes it as a site for high-school games.10 Between 1923 and 1929 the Black press reported frequently on games played, mostly by semipro Black teams playing against White teams. The Inquirer featured stories about games played by the (White) Lit Brothers team, made up primarily of employees from that department store, against Black teams including Ed Bolden’s Hilldale Daisies at “Forty-eighth and Spruce” in 1925.11 The Lit boys, as they were known, also played “at their home field” against the Black Wilmington Potomacs that year.12 In 1926 the local Black weekly, the Philadelphia Tribune, reported that the Newton Coal Athletic Association team had exclusive use of Lit Brothers’ Field.13 In 1927 the (White) Philadelphia Elks, managed by sports promoter and booking agent Ed Gottlieb (1898-1979), called 48th and Spruce home.14

In 1928 Hilldale played several games at Spruce Field or Elks Park as it was also called in the press.15 After July 4, the Daisies played their Thursday home games there, although they scheduled a lucrative meeting with the House of David in Darby, the park they generally called home, which had a larger capacity.16 The Homestead Grays came to town to play Hilldale at Passon Field at the end of the season. The Pennsylvania Giants also called Elks Park their home field on Tuesdays and Fridays.17

Harry Passon, the Jewish owner of a sporting goods store, played a strategic role in promoting both black and white semi-pro baseball in Philadelphia. (Courtesy of the Passon Family)

By the end of the 1928 season, it was obvious to Harry Passon (1897-1954) that this field had become a popular place to play semipro baseball games, especially for Black teams that were growing both in number and in popularity as the Black population in that area also grew, and he came up with a plan to lease the field and rename it Passon Field. Passon was the owner of the leading sporting goods store in Philadelphia. The store, originally known as PGB Sporting Goods, opened in 1920. It was the joint project of Passon, Ed Gottlieb, and Hughie Black, hence the name featuring their initials. Passon (and his brothers) played baseball and basketball in their youth, but Harry soon realized that his main interest and personal strength was in the business side of sports. He bought out Gottlieb and Black, renamed the store Passon’s Sporting Goods, and employed family members to help him run the store, which supplied high quality equipment and uniforms to local teams. But the store at 507 Market Street not only sold goods – it also became the hub of the Philadelphia sports world. It was the home for the Passon Athletic Association and all the Passon clubs the Association sponsored – baseball, basketball, boxing, track and field, and soccer. Ed Gottlieb, former business partner and then leading promoter and booking agent, and owner of the Philadelphia SPHAS teams, maintained his agency in the building until 1944.

Gottlieb was responsible for most of the bookings in the greater Philadelphia area, and later extended his reach more broadly in the Northeast corridor.18 The store, and Gottlieb’s adjacent office, were where anyone involved in sports in Philadelphia came to meet, buy equipment, make deals, and schedule games.

Passon leased the field at 48th and Spruce from the Price estate. There were many reasons he decided to do this. The field would become a regular source of income from scheduling fees from the games held there that would be arranged and promoted by Ed Gottlieb. Making sure the arena would be known as Passon Field created a real opportunity to advertise the Passon brand, which was becoming a household word in the Philadelphia sports community.19 Since the short-staffed weekly newspapers usually printed whatever information promoters and managers sent them to fill their sports pages, Passon made sure the new name was well advertised. 48th and Spruce officially became Passon Field in April 1929 when the Tribune announced that the Homestead Grays, Baltimore Black Sox, and Bacharach Giants would be playing there that summer.20 The (White) Passon club team that the store sponsored also played its home games there.21

The grounds needed improvements. By May, Passon had added 1,500 new seats in hopes of making the location an even more popular attraction for Black and White audiences.22 In August the Pittsburgh Courier’s W. Rollo Wilson wrote that “the largest crowd ever at Passon Field” came to see the illustrious Homestead Grays.23 In his new role as proprietor of the field, Passon got involved in the legal struggle against the 1794 Pennsylvania blue law that prohibited the playing of baseball on Sundays.24 He and other team owners in Philadelphia understood that not being able to play on Sundays, when people had time to attend games, was causing a serious loss of revenue and opportunity. Most other states had abolished blue laws, or never enforced their centuries-old laws. The law in Pennsylvania was particularly irksome, as it specifically prohibited playing games on the Christian Sabbath. Connie Mack’s Philadelphia Athletics team made the first major challenge to the law in 1926. The Athletics lost a long legal battle, and Sunday baseball remained prohibited.

The Tribune regularly protested the prohibition25 as did teams and their owners who understood baseball as a leisure activity that in no way dishonored the Sabbath and were enraged by the hypocrisy of the state permitting other leisure activities, like miniature golf, while baseball was targeted. On Sunday, September 1, 1929, the (White) Passon club played a game against the Negro League star Louis Santop’s Broncos at Passon Field in defiance of the law. Both managers (Santop and Malcolm McGowan) were arrested and fined. They paid the $10 fine and the incident received only scant attention.26

The following August, however, another Passon Field challenge to the Sunday laws became national news. This time two White teams, the Passons and the North Penn Athletic Club, held a contest on August 3, 1930. The two managers (Malcolm McGowan and Edward Sherman) went into the stands to pass the hat, which Passon believed challenged the commercial aspect of the Sunday law. Three policemen arrested the managers and the umpire (Todd Voorhees) and charged them with disorderly conduct. This time they refused to pay the fines and they were sentenced to 30 days in jail. Passon and his lawyer, Michael Saxe, also filed a complaint against the arresting officers, claiming they were in violation of another old Pennsylvania law that prohibited police from making arrests on the Sabbath without a warrant. The local newspapers, Black and White, followed the story closely. Although the defendants were initially found guilty, a sympathetic appeals judge, Edwin O. Lewis, overturned the judgment, ruling:

“The evidence produced before us as to the conduct of the baseball game on August 3 does not establish that disorderly conduct amounting to a breach of the peace was committed by all or any one of the defendants. Their arrest on Sunday without a warrant was therefore unlawful, the whole proceeding being without effect and void.”27

Lewis’s extensive and well-publicized ruling28 also supported legalizing Sunday baseball as an opportunity to reduce crime. However, the ruling only supported amateur Sunday baseball in nonresidential areas. He allowed the teams to take up a collection in the stands, but not if it was a “subterfuge” for paid admission. He further stipulated that since Passon Field was in a residential area and near a hospital, apartment house, and a miniature golf course, baseball games on Sunday would be considered a disturbance of the peace even if acceptable on other days. Police could therefore stop games and disperse Sunday crowds at Passon Field, but not make arrests without a warrant.29

By drawing attention to the law and clarifying its scope, Passon made an important contribution to the effort to keep the law in the news. Using the courts to overturn the law, as Connie Mack discovered before him, would not be a successful strategy. However, both efforts drew public attention to the need to change the law and encouraged the governor and the legislature to act. It would take a major legislative battle and ultimately a public referendum for Sunday baseball (at least between the hours of 2 and 6 P.M.) to become legal in 1934.

At the beginning of the 1930 season, the Tribune reported that plans were underway for Ed Bolden (1881-1950), who was no longer involved with the Hilldale team that he had built and managed, to start a new team, the Hillsdales, and that they would make Passon Field their home park. He shipped the team’s equipment he had stored in Darby to 48th and Spruce.30 An article in the Chicago Defender called Passon’s “rebuilt park … one of the best semipro diamonds in this city” and a logical place for Bolden to start over since the Hilldale team had been playing there regularly the year before.31 The Baltimore Afro-American claimed that Ed Gottlieb had been hired as the business manager.32 But when Bolden learned that the Lincoln Giants also planned to make Passon Field their home base that year,33 fearing that there would be too much local competition and hence insufficient revenue, he changed his mind about fielding the team for that season. Dick Sun reported in the Tribune that another reason this plan never materialized was that most of Hilldale’s players stayed with the Darby team, and Randy Dixon maintained that it was Bolden’s reliance on the “Nordic” support of Gottlieb and Passon that made Bolden’s efforts less appealing to the players and fans.34

Although Bolden’s plan to develop a new team with Gottlieb and Passon’s help did not come to pass, rumors continued to surface in the winter of 1931 about Bolden’s new team. Speculation was that it would be operated by former Hilldale star John Henry “Pop” Lloyd and sponsored by “the Passon interests.”35 Perhaps inspired by these possibilities, Passon decided to field his own independent Black team, which he called the Bacharach Giants after the Eastern Colored League team that had been playing in Atlantic City (and occasionally at Passon Field) but that had folded in 1929 due to financial difficulties. Passon had installed arc lights to his newly refurbished field, and they would play there on Monday evenings, traveling on Wednesdays and Saturdays. He hired former Hilldale star Otto Briggs as the manager, and other former Hilldale greats, including Turkey Stearnes and Pop Lloyd, also joined the team.36 They did well in 1931 and 1932, when they played against topflight opponents including the Pittsburgh Crawfords, Homestead Grays, and New York Black Yankees.37

After their strong season in 1932, Passon planned to field the “Bees” (as they came to be known) again in 1933. Given their success, Passon made more improvements to his field, adding a grandstand, clubhouse, and a more sophisticated lighting system.38 Malcolm McGowan, the Bacharachs’ general manager, commented in the Tribune:

“After the improvements are finished the park aside from being the most convenient one, will be the most beautiful one in the city. The admission prices are going to be in reach of everyone even a small girl or boy will be able to get in.”39

Ed Bolden, meanwhile, started a new independent Black team, the Philadelphia Stars. Instead of working with Passon as had been rumored, Bolden enlisted Ed Gottlieb to run the business side of the Stars. Bolden and Gottlieb would own the Stars together, with Gottlieb remaining the financial power and silent partner, until Bolden’s death in 1950, when Gottlieb took control, with Bolden’s daughter Hilda becoming the nominal owner. For the 1933 season Bolden and Gottlieb made the newly refurbished Passon Field the Stars’ home, and it remained home field for the Bacharachs as well. The Tribune highlighted the Stars’ practices at Passon Field before the season began.40 The Bacharachs and Stars were the top two Black teams in the area, and played their games against each other at Passon Field, including a five-game series in June. (The Stars took three out of the five games.)41 The Black press built it up as a rivalry, probably at Bolden and Gottlieb’s urging, to encourage fan interest.42 In addition to games against each other, both teams played against Passon’s White team.43 Both teams also held contests against Gottlieb’s White Jewish team, the SPHAS, as well as popular traveling teams that Gottlieb booked, like the House of David.44 At the end of the season the Stars also played against teams from the newly formed Negro National League, but those contests were held at Penmar Park and the Hilldale Stadium, not Passon Field.45 It therefore did not come as a surprise in February of 1934 that Ed Bolden announced that the Stars would have a new home field the following season, Penmar Park, located at 44th and Parkside, owned and operated by the Pennsylvania Railroad.46

The winter of 1934 proved to be eventful. As a result of Connie Mack and Harry Passon’s earlier efforts and with other sports magnates putting additional pressure on the governor and legislature, a voter referendum was passed that finally allowed Sunday afternoon baseball in Philadelphia, creating new possibilities for games at Passon Field.47 Although in February Bolden had stated publicly that the Stars would be playing elsewhere, in March he announced that the Stars would, in fact, play all their Saturday night and Sunday home games at Passon Field. At Bolden’s urging, Passon agreed to add 4,000 seats, renovate the field, and upgrade the lighting for night games.48

This turn of events was surprising given the tensions between Bolden and Passon over the entry of the Stars and Bacharachs into the Negro National League. Gus Greenlee’s new league was started in 1933, but neither Philadelphia team was interested in applying for membership at that time despite Greenlee’s invitation to the Stars that Bolden turned down, citing his difficult experiences with league play when he operated the Hilldale team.49 But Bolden was persuaded by the new circumstances available in 1934: Sunday afternoon games in Philadelphia, Passon’s upgrading of the lighting and capacity at Passon Field (and better lighting in many parks), and the overall economic climate that seemed to be improving, finally, after the 1929 stock market crash, all of which would encourage better attendance at games and improve the financial viability of league play.50

Passon was also eager for his Bacharachs to join the league. He was interested in putting his players on salary rather than using the “co-op system” that had proved difficult to manage in prior years, and that he believed to be unfair to the players.51 But Bolden and presumably Gottlieb were not enthusiastic about including the Bacharachs. He told Gus Greenlee and the other team owners that the Stars would not join the league if the Bacharachs were included. The reason he gave publicly was that he did not believe Philadelphia could support two league teams economically, a reason he had given in 1930 when he folded his new Hillsdale team at the beginning of the season. Several of the other owners argued that the competition would be good for the league, and Cum Posey, owner of the Homestead Grays, noted that it would work if they didn’t play in Philadelphia on the same day.52

Bolden and Gottlieb, however, were looking to elevate the Stars and did not want the Bacharachs cutting into their profit margin or public attention. Passon graciously withdrew his application for full membership, although Tribune reporter Randy Dixon described Passon as “shocked.”53 Since Gottlieb was in business with both Passon and Bolden, the hard position Bolden and Gottlieb took on membership, and their interest in playing in other venues surely must have distressed Passon. Ultimately, the Bacharachs would be welcomed by the league as associate members for the first half of the season,54 and would become full members in the second half.

The Passon Field Negro National League season began on May 12, 1934, a game between Ed Bolden’s Philadelphia Stars and Dick Lundy’s Newark Dodgers. League Commissioner and sportswriter W. Rollo Wilson described Lundy in his “Sports Shots” column in the Pittsburgh Courier as “baseball’s greatest shortstop” and lauded the new league for its quality.55 There was a celebratory opening ceremony with the Octavius V. Catto Band playing and Commissioner Robert Nelson of the Pennsylvania State Athletic Commission tossing the first ball. The advertisement in the Tribune noted the 4,000 new seats and admission prices of 25 cents for those seats and 35 cents for the newly refurbished grandstand.56 The Stars won, 12-0, behind the pitching of Stewart “Slim” Jones, who would be their star and main attraction in this banner year for the team. Some 5,000 fans were in attendance and appreciated the new features of the field.57

The first half of the season ended in early July. The Stars were in second place. The Bacharachs had done well in league competition and Bolden did not raise objections when they became full members.58 To keep enthusiasm high for the second half, the Bacharachs and Stars initiated a competition, a five-game series at Passon Field to determine the city championship. A “well-known downtown sportsman” (probably Passon himself) donated a trophy for the winners, and the Tribune reported that Bolden and Passon made a wager on the games, with Gottlieb as the “stakeholder.”59 The Stars won four out of five games, with Slim Jones the winning pitcher in two of the contests.60

The second half of the season went well for the Stars, but not for the Bacharachs. Passon Field also experienced some difficulties. Racial tensions were rising in the neighborhood.61 In August Passon hired an attendant to keep the peace and collect balls that a “gang of hoodlums” hanging out near left field all summer had been taking. The attendant was beaten by the “gang.” When a detective from the local precinct who was attending the game pursued them, he too was hit, but managed to apprehend two of the alleged assailants.62 This situation caused Passon to consider ending night games at the field. Passon was also criticized by visiting league teams for the low admission prices, and he was persuaded to make admission prices comparable to those in other cities, raising Sunday prices from 40 to 55 cents.63

While the Bacharachs faded (and would not rejoin league play in years that followed), the Stars were the NNL winners of the second half and went on to play in a championship series against the first-half winners, the Chicago American Giants. The Stars’ four home games were played at Passon Field to crowds that numbered from 2,000 to 5,000. They lost the first game at home. Three were planned but could not take place because of inclement weather.64 They won only one of three games in Chicago.65 The series was then interrupted by a series of exhibition games, held at Yankee Stadium, with 25,000 spectators. In a doubleheader, the Giants beat the New York Black Yankees and the Stars tied the Pittsburgh Crawfords.66 The large size of the mixed-race crowd was probably the result of Satchel Paige pitching for the Crawfords. Slim Jones held his own against Paige for the Stars. The championship series could not compete with the money to be made in New York.67

Ed Gottlieb claimed responsibility for the interruption of the series. As Gottlieb recalled in a later interview:

“That was the first four-team doubleheader in Yankee Stadium. We came in with the Pittsburgh Crawfords in the first game against the Philadelphia Stars, and in the second game it was the New York Black Yankees against the Chicago American Giants. It rained the whole night before the game and really didn’t stop until just before the first game started, but we had 25,000 there, and the concessions were treemendous [sic]. Slim Jones – he died of pneumonia when he was still very young – he was pitching for the Stars. Oh, he was fast! And we had Satchel pitching for the Crawfords. It was a 1-1 tie, so we called it in the 10th inning with the idea in mind that we could repeat the whole damn game a few weeks later, which we did. And you know, we got just about the same gate all over, even though, just like the first time, it rained right up until the game started.”68

The Stars went on to win the last games at Passon Field when play was resumed. They had to play four games because what would have been the seventh and final game could not be completed before the 6 P.M. curfew required by the revised Sunday blue law. The series was also marred by violence, not by “rowdy fans” but by players physically attacking umpires and each other; clearly the outcome mattered to them. Slim Jones won the eighth game with both his pitching and hitting, but since they were playing on a weekday because of the attenuated game seven, the crowd was only 2,000 and the series gathered little press.69

After that year Bolden and Gottlieb would no longer make Passon Field their home ballpark. Gottlieb took out a lease at Penmar Park at 44th and Parkside in 1935, which boasted more seating accompanied by much soot and dust as the result of its location near the Pennsylvania Railroad roundhouse.70 The Stars did continue to play some games at Passon Field in 1935.71 In the first half of the 1936 season they played regularly at Passon Field on Sundays.72

In July of 1936, Passon Field’s stands were condemned, and no baseball games were played there for the rest of the season.73 That fall football, soccer, and boxing matches were held there,74 and baseball games started again in 1937 although few were noted in the press.75 Unlike Gottlieb, who stayed busy promoting the NNL and the Stars, Passon had lost interest in the goings on at the field and often failed to inform the Tribune about what was happening there. The Bacharachs and the White Passon team (often called the “storeboys”), under the guidance of Malcolm McGowan, continued to play independent semipro ball, often against Negro League teams. In 1937 Passon’s employee at the store and former Negro League player Tom Dixon was the Bacharach manager who discovered 15-year-old Roy Campanella. Campy played with the Bacharachs in May and June that year. There is no record of his playing at Passon Field during his time with the Bacharachs.76

In 1937 Passon Field again gained notoriety when world heavyweight champion Joe Louis brought his softball team, the Brown Bombers, to play against Chickie Passon’s (White) Philadelphia All-Stars in a game arranged by Harry Passon. The crowd was estimated by police at 20,000, obviously beyond the capacity of the field. When Louis arrived for batting practice and hit a few balls out of the park, the enthusiastic crowd stormed the field, and the newly rebuilt grandstand collapsed, injuring five people. The game was played the next day at Municipal Stadium.77

The Philadelphia Inquirer’s regular coverage of games at Passon Field, which included baseball teams from industrial leagues, softball, high-school football, and soccer, continued through the 1939 season. In 1941 the “old” Passon Field was only mentioned as the location for parades for British War Relief. In 1942 the stands had been torn down and the field was vacant, although a 1942 land-use map still calls the area Passon Field.78 The students at neighboring West Philadelphia High School, whose baseball and football Speedboys teams had played there in years past, requested that the School District buy the land for their school.79 Before that would come to pass, in 1943 the Price estate permitted the field to be repurposed as 200 World War II Victory Gardens.80 A Philadelphia Evening Bulletin photograph from March 1944 had this caption: “Some 200 gardens measuring 25 by 25 feet are laid out across this tract (formerly Passon Field) for victory gardens.”81 The field at 48th and Spruce was Passon Field no more. The Price estate attempted to sell the field for commercial use in 1947, but the City Council would not rezone the property because the Welfare and Recreation Department had other plans for it.82

In 1948 the Price estate sold the field to the City of Philadelphia’s Department of Recreation. In 1950 the School District obtained the title. From then on it would be known as the West Philadelphia High School Athletic Field. In addition to the Speedboys, many high-school and amateur football, soccer, and baseball teams played their games there and it was the location for track and field meets as well. The Recreation Department continued to use it as a community center and a playground that was open for the public during summers in the 1960s.83

In 2002 the field was renamed Pollock Field in honor of the West Philadelphia High School alumnus and Alumni Association head Joseph L. Pollock. Pollock, who graduated in 1940, grew up poor in West Philadelphia and credited West Philly High with enabling him to get a good education and ultimately a good life. It is likely that he was among those students and recent alums who petitioned to turn Passon Field into his school’s athletic field in 1942.84 In 2014 the field received an upgrade with new lighting,85 and the West Philadelphia High School Speedboys (and Speedgirls) football, soccer, and lacrosse teams continue to use the field. Although the baseball team no longer plays there, their presence is commemorated in a “Speedboy” mural.86

Notes

1 Sections adapted from Rebecca T. Alpert, “Harry Passon: Philadelphia Baseball Entrepreneur,” in Morris Levine, ed., The National Pastime: From Swampoodle to South Philly (Phoenix: SABR, 2013), 64-68. I also relied on John L. Puckett, “A Storied Athletic Venue in West Philadelphia: From Passon Field to Pollock Field,” West Philadelphia Collaborative History website, accessed July 1, 2022; Courtney M. Smith, Ed Bolden and Black Baseball in Philadelphia (Jefferson North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2016), and Neil Lanctot, Negro League Baseball: The Rise and Ruin of a Black Institution (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004), as well as the ProQuest Historical Newspaper Digital Collection. I am grateful to Lynn Alpert, who helped with research and photography.

2 Philip Lowry, Green Cathedrals: The Ultimate Celebration of All 271 Major League and Negro League Ballparks Past and Present (Reading, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley Publishing, 1992).

3 See Douglas Ewbank, “Migration and Immigration,” West Philadelphia Collaborative History website, https://collaborativehistory.gse.upenn.edu/stories/migration-and-immigration, accessed July 24, 2022.

4 From 1923 to 1929 the field was known as Elks Field, Lit Brothers Field, or Spruce Field. From 1929 to 1942 it was called Passon Field. From 1943 to 1945 it served as a World War II Victory Garden. From 1950 to 2001 it was known as the West Philadelphia High School Athletic Field. In 2002 it was renamed Pollock Field to honor a celebrated alumnus. Throughout its history it has often been referred to simply as “48th and Spruce.”

5 The Lit Brothers department store’s team often played there, as did the team known as the Philadelphia Elks that was managed by Ed Gottlieb. I found no reference to any legal or special relationship either to the department store or to the team. It could have been called Elks after the fraternal organization, which wanted an Elks Field in every town where there was a chapter. “Elks Start Big Move to Start Playgrounds,” Washington Post, June 6, 1922: 8.

6 George W. Bromley and Walter S. Bromley, “Atlas of the City of Philadelphia, wards 24, 27, 34, 40, 44 & 46, West Philadelphia, from actual surveys and official plans,” published by G.W. Bromley, Philadelphia, 1927, plate 24; Free Library of Philadelphia Digital Map Collection.

7 Eli K. Price was also described as a “speculator in West Philadelphia real estate.” https://collaborativehistory.gse.upenn.edu/media/eli-k-price.

8 Price family papers (Collection 4163), Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Box 27, folders 6-7. The finding aid for the collection details the family history. http://www2.hsp.org/collections/manuscripts/p/Price4163.html, accessed August 5, 2022.

9 Ordinances of the City of Philadelphia from January 1 to December 31, 1948 (Philadelphia: Dunlap Printing Company, 1949), 220-221. The ordinance refers to the property as a playground and recreation center. The trustees (J. Sergeant Price, Philip Price, and E. Gwen Martin) were cultural leaders in Philadelphia.

10 The Philadelphia Inquirer, May 24, 1923: 21, called it Lit Brothers Field when describing one high-school game that was played there, but most of that summer the field was referred to as 48th and Spruce in reference to games played there.

11 “Washington’s Double Wins for Hilldale,” Philadelphia Inquirer,July 18, 1925: 11 .

12 “Hampton Causes Potomacs Downfall,” Baltimore Afro-American, May 2, 1925: A14.

13 “Newton Team Gets Lit Brothers Field,” Philadelphia Tribune, April 17, 1926: 10.

14 “Elks Down Wilmington Potomacs By 5-3 Score,” Philadelphia Tribune, September 15, 1927: 10. Other teams also called 48th and Spruce home in 1927, including the Philadelphia White Socks. There were 2,000 fans at their opening game. The field was booked by W.A. Ringold, who could be reached at 4513 Wallace Street, or by phone, Baring 8687, if a team wanted to book a game. “White Sox Open Season With Victory,” Philadelphia Tribune, May 19, 1927: 11. See also Rich Westcott, The Mogul: Eddie Gottlieb, Philadelphia Sports Legend and Pro Basketball Pioneer (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2008), 67.

15 “Hilldale Secures Local Grounds,” Philadelphia Tribune, March 22,1928: 11. Rollo Wilson, “Sports Shots,” Pittsburgh Courier, April 7, 1928: A4.

16 “Hilldale Club Battles House of David,” Philadelphia Tribune, June 28, 1928: 11.

17 “Homestead Grays to Meet Daisies Here,” Philadelphia Tribune, September 6, 1928: 11. “Pennsy Giants See Games in Balto.,” Baltimore Afro-American, June 30, 1928: 12.

18 Gottlieb kept his offices above Passon’s store at 507 Market until 1944, when he moved the office to 1537 Chestnut Street. Letter from Ed Gottlieb to Effa Manley, January 24, 1944, Newark Eagles Papers.

19 There were at least two other fields that Passon named “Passon Field,” one in the Germantown section at Chelten and Magnolia (“SPHAS Turn Back Hilldale Foemen,” Philadelphia Inquirer Public Ledger, May 27, 1925: 25) and another in the Northeast at Kensington and Torresdale Avenue (“North Catholic Blanks Mastbaum at Soccer,” Philadelphia Inquirer, November 6, 1940: 34).

20 “Prof. Leslie Pinckney Hill to Throw Out First Ball,” Philadelphia Tribune, April 18, 1929: 11.

21 “Atlanta Giants in Win Over Passons,” Philadelphia Tribune, May 23, 1929: 10.

22 “Hilldale Clan All Set for Baltimore,” Philadelphia Tribune, May 2, 1929: 10.

23 Rollo Wilson, “Sport Shots,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 3, 1929: A5.

24 John A. Lucas, “The Unholy Experiment – Professional Baseball’s Struggle Against Pennsylvania Sunday Blue Laws 1926-1934,” in Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies, 38:2 (April 1971), 163-175.

25 See for example, “Blue Sunday Laws,” Philadelphia Tribune, July 25, 1929: 16.

26 “Broncos Leading by One Run When Police Break Up Game,” Philadelphia Tribune, September 5,1929: 10.

27 “Free Donations at Sunday Games Upheld by Lewis,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 23, 1930: 1.

28 Three Sentenced for Sunday Ball Game in Philly,” Syracuse Herald, August 5, 1930; “3 Men Get 30 Days for Sunday Ball,” Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, August 4, 1930.

29 “Free Donations at Sunday Games Upheld by Lewis, ”Philadelphia Inquirer, August 23, 1930: 3.

30 “Ed Bolden to Organize New Ball Outfit,” Philadelphia Tribune, April 10, 1930: 10.

31 “Ed Bolden Is Head of New Ball Outfit,” Chicago Defender, April 19, 1930: 8.

32 “Name Briggs Leader,” Baltimore Afro-American, April 19, 1930: 14.

33 “Lincoln Giants Open as Philly Home Team,” Philadelphia Tribune, May 15, 1930: 10.

34 Dick Sun, “Bolden Gesture Fades,” and Randy Dixon, “Sport Sidelights,” Philadelphia Tribune, April 24, 1930: 11.

35 Randy Dixon, “Money Man Aligns with Hilldale Team,” Philadelphia Tribune, February 26, 1931: 10. The following section is adapted from Alpert, “Harry Passon,” The National Pastime.

36 “New Bacharach Giants Test Mettle with Camden Sunday,” Philadelphia Tribune, June 18, 1931: 10.

37 “Bacharachs Execute Triple Play,” Philadelphia Tribune, May 19, 1932: 11; “Bacharachs String of Eight Victories Snapped,” Philadelphia Tribune, July 7, 1932: 11; “Bacharachs Meet Acid Test in Game with Crawfords,” Philadelphia Tribune, August 25, 1932: 9.

38 “Quaker Team to Open Soon,” New York Amsterdam News, April 5, 1933: 9.

39 “Bacharachs to Keep Stars for Coming Season,” Philadelphia Tribune, April 6, 1933: 11.

40 Smith, Ed Bolden, 70; “Daily Practice Sessions for Phila. Stars,” Philadelphia Tribune, April 13, 1933: 11.

41 “Bolden’s Stars and Bacharachs Start Five Game Series,” Philadelphia Tribune, June 22, 1933: 11. Smith, Ed Bolden, 73.

42 “Boldenmen at Passon’s Wed.” Philadelphia Tribune, August 17, 1933: 10; “Bacharachs and Boldenmen Settle Dispute Saturday,” Philadelphia Tribune, August 24, 1933: 10; “Passon Nine to Meet Bacharachs and Boldenmen,” Philadelphia Tribune, August 31, 1933: 10.

43 “Negro Clubs to Oppose Passon ‘9,’” Philadelphia Tribune, July 13, 1933: 12.

44 “Bolden’s Nine Trims Bearded Clan by 5 to 1,” Chicago Defender, May 13, 1933: 9; “Passon Outfit Set to Check Bolden’s Stars,” Philadelphia Tribune, July 6, 1933: 10.

45 “Boldenmen Succumb to Smoky City Nine,” Philadelphia Tribune, September 7, 1933: 11.

46 “Ed Bolden Announces New Base Ball Plans,” Philadelphia Tribune, February 1, 1934: 11.

47 Lucas, “Unholy Experiment.”

48 “Bolden’s Team to Play All Games at New Passon Field,” Chicago Defender, March 24, 1934: A5.

49 Lanctot, Negro League Baseball, 27-28.

50 Lanctot, Negro League Baseball, 27-28.

51 Rollo Wilson, “Sports Shots,” Pittsburgh Courier, December 9, 1933: A4.

52 Cum Posey, “Cum Posey’s Pointed Paragraphs,” Pittsburgh Courier, March 3, 1934: A5.

53 Randy Dixon, “Baseball Magnates Convene in Parley,” Philadephia Tribune, February 15, 1934: 10; “Blacksox, Grays Not Included,” Pittsburgh Courier, February 17, 1934: A4.

54 Randy Dixon, “Wilson Named Landis of Negro Baseball,” Philadelphia Tribune, March 15, 1934.

55 W. Rollo Wilson, “Sports Shots,” Pittsburgh Courier, May 12, 1934: A4.

56 “Display ad 21,” Philadelphia Tribune, May 10, 1934: 20.

57 “Stars Topple Newark 12-0,” Philadelphia Tribune, May 17, 1934: 12; W. Rollo Wilson, “Phila Stars Win Opener,” Pittsburgh Courier, May 19, 1934: 14.

58 Pittsburgh Courier, July 7, 1934: A5.

59 “Bacharachs and Stars to Play Series,” Philadelphia Tribune, July 26, 1934: 12.

60 “Stars Drub Bees,” Philadelphia Tribune, August 2, 1934: 12; “Stars Down Passon,” Philadelphia Tribune, August 16, 1934: 12.

61 Smith, Ed Bolden, 80.

62 “Crack Detective Is Hurt,” Baltimore Afro-American, August 18, 1934: 19.

63 “Craws-Yanks Play Tonite; Stars Sunday,” Philadelphia Tribune, September 20, 1934: 11.

64 “Chicago Stops Stars in Playoff Start,” Philadelphia Tribune, September 13, 1934: 14.

65 “McDonald Wins,” Philadelphia Tribune, September 20, 1934: 11.

66 Ed Harris, “Points and Errors,” Philadelphia Tribune, September 13, 1934: 14.

67 Ed Harris, “Jones and Paige Duel to 1-1 Tie,” Philadelphia Tribune, September 13, 1934: 14.

68 Frank Deford, “Eddie Is the Mogul,” Sports Illustrated, https://vault.si.com/vault/1968/01/22/eddie-is-the-mogul, accessed July 30, 2022.

69 Ed Harris, “Stars Clip Giant for 2 Runs,” Philadelphia Tribune, October 4, 1934: 11. The headline read “Jones Hurls Boldens to Championship.”

70 Lanctot, Negro League Baseball, 201.

71 “Stars Tag Brooklyn,” Philadelphia Tribune, May16, 1935: 11; “Evans Hurls Mates to Win,” Philadelphia Tribune, May 23, 1935: 11; “Stars Drop Two Games,” Philadelphia Tribune, June 27, 1935: 12; “Casey Breaks Leg,” Philadelphia Tribune, July 18, 1935: 11; “Bill Yancey Honored at Career Peak,” Philadelphia Tribune, August 22, 1935: 9.

72 “Phila. Stars Start Practice,” Philadelphia Tribune, April 16, 1936: 12.

73 Ed Harris, “The Gossip Post!!!,” Philadelphia Tribune, July 23, 1936: 10.

74 “Wilmot Lions Tackle Lincoln,” Philadelphia Tribune, November 12, 1936: 11.

75 “Display Ad 13,” Philadelphia Tribune, June 17, 1937: 12. This advertisement for a Newark Eagles-Washington Elite Giants game was an exception.

76 Neil Lanctot, Campy: The Two Lives of Roy Campanella (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2011), 21-26. In June Campanella signed with the NNL’s Washington Elite Giants and began to work with his new mentor, Biz Mackey.

77 “Fourteen Hurt in Crash of Two Grandstands,” Philadelphia Inquirer Public Ledger, September 21, 1937: 2; “Five Hurt Treated at Louis Ball Game” Philadelphia Tribune, September 23, 1937: 3; “Fans Nearly Mob Joe Louis in Baltimore,” Baltimore Afro-American, September 25, 1937: 24; “Joe Louis Mobbed by Crowd of 30,000 in Philly,” Pittsburgh Courier, September 25, 1937: 1; “Louis Fans Wreck Stands,” Cleveland Call and Post, September 30, 1937: 10.

78 Philadelphia Land Use Map, 1942, Plate 4A-1 (Land-Use Zoning Project 18313, Plans and Registry Division, Bureau of Engineering Surveys and Zoning, Department of Public Works, Federal Works Progress Administration for Pennsylvania, Free Library of Philadelphia Digital Map Collection)

https://www.philageohistory.org/tiles/viewer/, Accessed August 10, 2022.

79 “West Phila. Students Petition to Take Over Passon Field,” Philadelphia Inquirer Public Ledger, March 18, 1942: 35.

80 “Corn Grows High in Phila. Too,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 11, 1943: 68.

81 “Row on Row,” Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, March 21, 1944. George D. McDowell Evening Bulletin Photographs Collection, SCRC, Temple University. https://digital.library.temple.edu/digital/search/searchterm/passon%20field/order/nosort accessed July 20, 2022.

82 Price Family Papers, Box 27, Folder 7.

83 “Playgrounds Open on July 1,” Philadelphia Tribune, June 18, 1963: 15; “Eighty-three Playgrounds Will Open on July 6,” Philadelphia Tribune, June13, 1964: 9; “School Playgrounds to Open July 1,” Philadelphia Tribune, July 1, 1969: 5.

84 Gayle Ronan Sims, “Joseph L. Pollock, 82, W. Phila. High Booster,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 9, 2004.

85 Aaron Carter, “Speedboys Are Stars Under the Lights,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 7, 2004. https://www.inquirer.com/philly/sports/high_school/pennsylvania/20140907_Speedboys_are_stars_under_the_lights.html. Accessed October 18, 2022.

86 In the early 2020s the field was upgraded with new equipment. There was a new football coach, and local alumni provided concession stands. The coach was unaware that the field had been renamed Pollock Field, and no marker to indicate the name was visible. (“Koach Bubb,” Personal interview with author, August 11, 2022).