Sixto Escobar Stadium (San Juan, PR)

This article was written by Rory Costello

This multi-purpose facility has been called “The Madison Square Garden of Puerto Rico.”1 Its use in boxing and basketball is a big reason, but the parallel extends to track and field, as well as political conventions. Baseball, however, forms an especially rich chapter in the history of Estadio Sixto Escobar (as it is known to its Spanish-speaking local fans). Pro ball has not been played at Escobar since February 1962, but it was the most storied ballpark of the Puerto Rican Winter League in its golden age. The San Juan Senators played there starting in 1938, when the league was founded. After the Santurce Crabbers joined the PRWL in 1939, they and the Senators shared the stadium – and an intense rivalry – for 23 seasons.

“Santurce’s fans and the old stadium were just great,” said Herman Franks, who managed the 1954-55 Crabbers – called “the greatest winter ballclub ever” by one of its members, Don Zimmer. “I don’t think the new stadiums had or will ever have the feeling of Sixto Escobar Stadium.”2

Trying to summon up that feeling in words alone is not truly possible, but in the effort to do so, one may start with the island’s fans. Author Thomas Van Hyning, who has chronicled Puerto Rican baseball in two books, devoted a whole chapter to them in the first of those books. He quoted numerous people – players, umpires, broadcasters, and more – about how “closely and religiously” those fans follow the game. At Escobar, they were close to the field, which heightened their noisy enthusiasm. The stadium officially seated 13,135 between its grandstands, box seat chairs, and the bleachers – but for big games, thousands more jammed in. Pitcher José “Palillo” Santiago, who pitched for San Juan and later for the Boston Red Sox, likened Escobar to Fenway Park.3

Another big factor was the high quality of Puerto Rican baseball. The list of stars is long: natives, other Latin Americans, plus many U.S. imports from the majors and Negro Leagues. There were a lot of dramatic moments at Escobar.

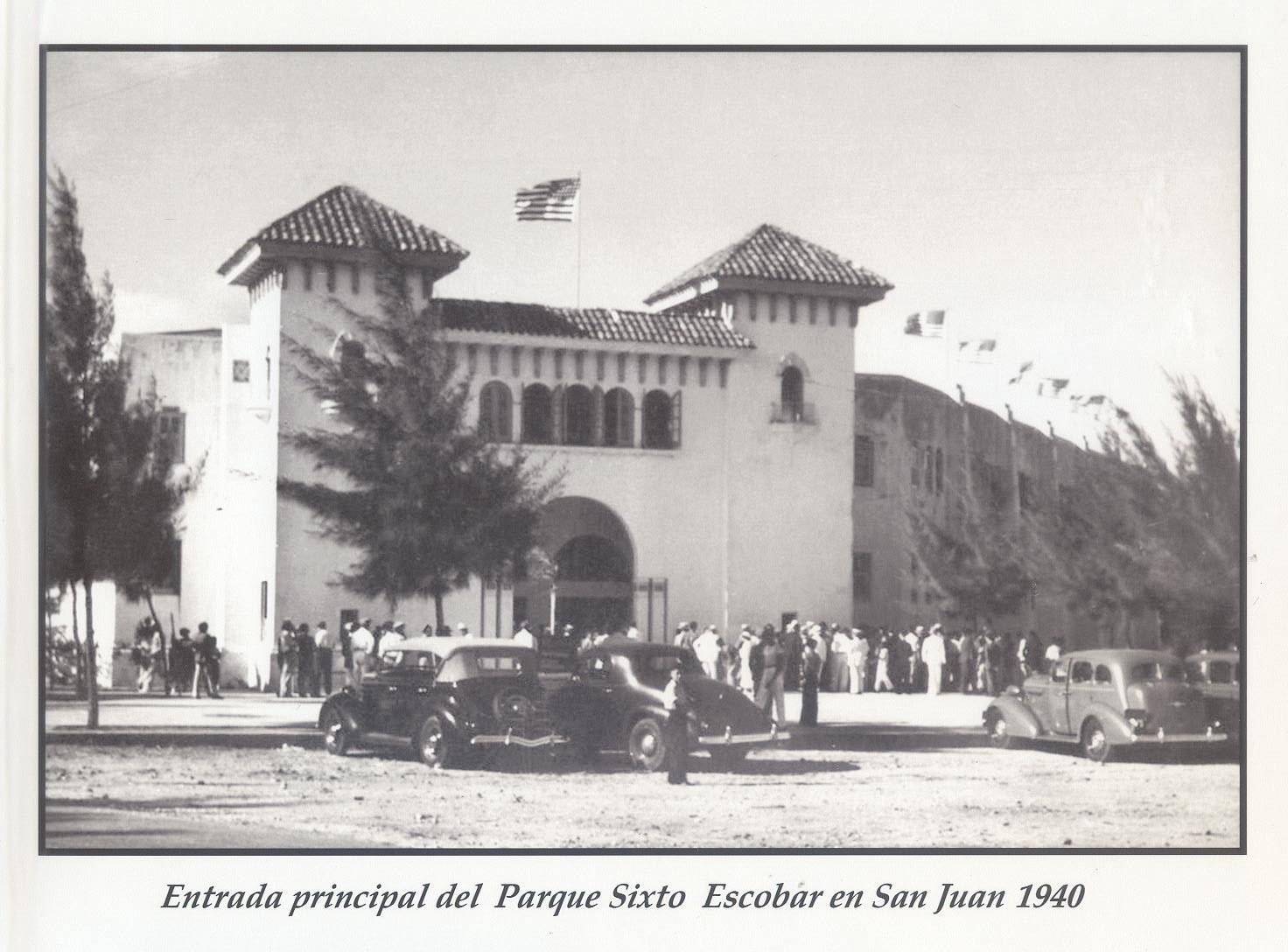

Sixto Escobar Stadium was originally called Estadio del Escambrón. It was renamed in April 1938 for star boxer Sixto Escobar, who was Puerto Rico’s first world champion in that sport. Naturally, the bantamweight – known appropriately as El Gallito (The Little Rooster) – became a big hero in a place that has produced many other great fighters and loves “the sweet science.”

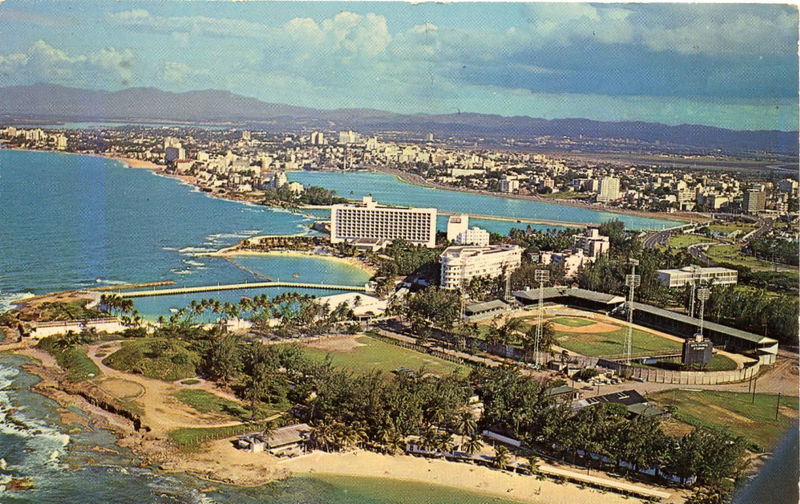

The original name of the park came from its location: Punta Escambrón, in the neighborhood called Puerta de Tierra, in the vicinity of Old San Juan. Nearby is one of San Juan’s public beaches, El Escambrón, which is known for its splendid views. Thomas Van Hyning wrote, “It was a comfortable stadium where one could feel the presence of the Caribbean trade winds.”4

Those swirling winds could also make outfield play tricky.5 Plus, they both gave and took away, as author Lou Hernández recounted. Félix Mantilla told Hernández that the ocean breeze would carry high fly balls, but Nino Escalera said that the winds tended to blow in from the beach. However, pitcher Jack Harshman said, “Sixto Escobar was a good ballpark, and it was a fair one. If you hit the ball real hard, you could get it out there. If you pitched real good, you had a chance to win. They did not get any cheap home runs there.”6

The geology of Puerto Rico and Punta Escambrón was beneficial. Tito Stevens, a longtime fan of the Crabbers, heard about it from his childhood hero (and later a good friend), pitcher Rubén Gómez. Gómez noted that it could rain in the afternoon but a game could be played the same night because the drainage was so good. The ballpark, like other structures along the island’s north coast, was built atop a coral reef.7

Just south of the stadium is Luis Muñoz Rivera Park, which opened in 1929. Luis Muñoz Rivera (1859-1916) was a poet who turned to journalism, with a focus on politics – in particular the issue of Puerto Rico’s autonomy. Muñoz Rivera entered politics himself, serving as resident Commissioner of Puerto Rico from 1911 until his death. In 1948, his son, Luis Muñoz Marín, became the territory’s first democratically elected governor. The Muñoz connection took on greater significance in view of Escobar Stadium’s role in Puerto Rican politics.

With the development of such a favorable spot, and given Puerto Rico’s love of baseball, it’s easy to see why the San Juan city fathers chose to locate a ballpark there. Plus, as authors Michael and Mary Oleksak observed, after the Great Depression struck, “baseball provided a diversion for the people. In 1930, to encourage this interest, the strapped local government nevertheless voted to build a new stadium.”8 Construction began in 1931. The architect was Rafael Carmoega, one of Puerto Rico’s most prominent people ever in that profession.9

The stadium opened on November 12, 1932.10 In December 1933, J. Francis Edwards, sports editor of the San Juan newspaper El Imparcial, wrote a letter to the Pittsburgh Courier. Edwards described the thriving baseball scene at Escambrón (he noted that a quarter-mile running track encircled the field). Games took place on Saturday and Sunday afternoons and on Sunday mornings. Edwards said, “The Islanders take their baseball seriously and even the amateur teams attract thousands to their games.” Those fans got to see many outstanding players of African descent, from both the U.S. and Latin America.11 The man responsible for this scene was a local operator named Tony Luciano, who won the rights at auction.12

Author Jane Allen Quevedo described attending baseball games in Puerto Rico as being “as much a social event as a sporting event. . .in El Escambrón, local fans filled the benches and even climbed into the trees outside the ballpark to secure a good vantage point.”13 One of the attractions was Hiram Bithorn, who became the first Puerto Rican in the major leagues in 1942.

On January 9, 1936, Powel Crosley, president and owner of the Cincinnati Reds, announced that his team would conduct part of its spring training in Puerto Rico. It was the first time that a major-league team visited the island.14 The club’s fast-talking general manager, Larry MacPhail, boasted, “We’re the most streamlined, modern major league outfit in baseball history.”15

The team’s trainer, Dr. Richard Rhode, gave MacPhail a positive advance report. “I was very much surprised to find the ballpark, known as Escambron Baseball Park, to be such an excellent layout. It compares favorably with anything in the American Association except that it has a skinned infield.”16

Managed by Chuck Dressen, the Reds started training at Escambrón on February 10, though many of the players were so badly seasick after their ocean voyage that they could not practice for several days. Another contingent arrived by air, which also proved to be an adventure. Games began on February 27. The lineup for the opponents, Ponce, included such talent as the early Dominican star Tetelo Vargas, as well as local heroes Pancho Coimbre and Perucho Cepeda, father of Orlando Cepeda.17

Early March brought interesting reports of the Reds’ action from the Virgin Islands Daily News. One notable game took place on March 1, when the Almendares club of Cuba beat Cincinnati 5-1. “One-man team” Martín Dihigo was back on the mound after going three innings the previous day. He defeated Paul Derringer. The following day, the Reds returned to Escambrón for a doubleheader against a Negro League team, the Brooklyn Eagles. In the morning’s game, Brooklyn started Hiram Bithorn, who got the call after Leon Day was sick – Bithorn had impressed the Eagles in practice games.18 The 19-year-old allowed just one run in his first seven innings but got no decision after giving up three in the eighth. Brooklyn won the opener, 5-4, but Cincinnati got a split when Tony Freitas won in the afternoon, 3-2.19

The story of how the stadium came to bear Sixto Escobar’s name began in the mid-1930s as El Gallito became a prime contender in his weight class. On August 31, 1936, he became the undisputed bantamweight champion of the world. Later that year, he lost two non-title bouts to Harry Jeffra, sandwiched around one successful defense of his title at Madison Square Garden.

Escobar’s next outing – the first championship bout ever to take place in San Juan – came at Estadio del Escambrón, on February 21, 1937. He won a unanimous decision over Lou Salica, another of his main rivals, before a crowd of 26,000 (for boxing, it was possible to install thousands of temporary seats on the field around the ring). The referee was former heavyweight champ Jack Dempsey, who “kept the little men at it hammer and tongs throughout.”20

Escobar lost his title to Jeffra at the Polo Grounds in September 1937 – but regained it at Escambrón on February 20, 1938. He won a unanimous decision after knocking Jeffra down three times in the 11th round and once in the 14th. Again, capacity was boosted, this time to an estimated 18,000.21 That April, the Legislative Assembly of Puerto Rico voted to name the stadium and surrounding park in honor of Sixto Escobar.

In the winter of 1938-39, the Puerto Rican Winter League began operations. For its first three seasons, it was a semi-professional circuit, in affiliation with the National Baseball Congress on the mainland. The league’s first champion was the Guayama Brujos. Several months later, in September 1939, Escobar was the scene as Guayama faced the U.S. semi-pro champions, the Duncan Cementers from Oklahoma. Seating was again expanded for the series (although details are lacking).22 Guayama won, four games to two. Before facing Duncan, Pancho Coimbre said, “If I can hit Satchel Paige and Raymond Brown, why would this be any different?”23

Santurce entered the league for the 1939-40 season. This sparked a long-running tradition: the city championship of San Juan. A local baseball figure named Heriberto Ramírez de Arellano – a.k.a. “Don Guindo” – hatched the idea that awarding a banner to the winner of the “battle for the city’s supremacy would stimulate fan interest and attendance.”24 In the 23 years that they shared Escobar, the Crabbers won the regular-season series 14 times and the Senators eight, with just one year ending in a split. Overall in that period, the Crabbers won 188 games and the Senators 148.

The honor of most league championships for Escobar’s home teams also went to the Crabbers:

- Santurce won five times (1950-51, 1952-53, 1954-55, 1958-59, and 1961-62).

- San Juan won thrice (1945-46, 1951-52, and 1960-61).

Various imported stars came to Puerto Rico in the winter of 1939-40. At their head were Paige (whom Coimbre had previously faced elsewhere) and slugger Josh Gibson, who joined Santurce. However, Guayama repeated as Puerto Rican champion. In addition to Paige, the team featured Tetelo Vargas and Perucho Cepeda.

Sixto Escobar Stadium assumed its role in Puerto Rican politics when a convention was held there on June 21, 1940, officially creating the Democratic Popular Party (Spanish acronym PPD) with Luis Muñoz Marín as president. A Republican Union Assembly followed that August 18, and there would be more rallies to come over the course of the 1940s and 1950s.

A few months later in 1940 (late September and early October), the semi-pro “world championship” was held again at Escobar. This time the U.S. champion – the Enid Refiners, another Oklahoma-based team – beat Guayama, despite the batting of Vargas, who went 16-for-24.25 It must have been crushing for the Puerto Rican fans, because Enid won the seventh and final game, 7-5, with a four-run rally in the ninth inning.26

Josh Gibson wasn’t there in 1940-41, but at least three Hall of Famers came to Escobar as visiting players that winter: Buck Leonard (Mayagüez), Leon Day (Aguadilla), and Roy Campanella (Caguas). Gibson came back for the winter of 1941-42. He hit 13 home runs, including a number of the prodigious blasts that formed his legend. By some accounts, his last that season (and last in Puerto Rico) was the longest ever at Sixto Escobar Stadium – “a 600-foot rocket that sailed over Escobar’s pine trees on its way to the Escambrón beach.”27

As is the case with many reports of Josh Gibson homers, though, the distance may have been exaggerated. According to José “Pantalones” Santiago (no relation to Palillo), Gibson “played when there was no outfield fencing at Sixto Escobar. Gibson’s home run distances were helped by their bounces.”28

The PRWL became fully professional with the 1941-42 season. Charlie García de Quevedo, who later served as the league’s president, pushed for the upgrade, citing Escobar as an important model for the game locally. García put it this way: “Baseball will not have matured until the other towns and cities that participate in it have a park like Sixto Escobar.”29

Another Hall of Famer made his first appearance in Puerto Rico that winter: Willard Brown, who would later dazzle Escobar fans with his batting for Santurce. Brown played second base for Humacao and batted .409, second behind Gibson’s .480. Despite this auspicious season, though, Brown would not return to the island for another five years.

The 1945-46 Senators became Escobar’s first champion home team. They featured an outfield of homegrown stars: Luis Olmo, Freddie Thon Sr. (grandfather of future big-leaguer Dickie Thon), and Félix “Fellé” Delgado (who later became a notable scout). They were led, however, by the league’s MVP that year – Monte Irvin, who was playing out of position at second base to help the team. The pitching staff was anchored by two other very capable Negro Leaguers, Johnny Davis and Roy Partlow.

Willard Brown became a Crabber starting with the 1946-47 season. He led the league in batting that winter at .390, edging out Irvin (.387). Shortly after the season ended, Puerto Rico again welcomed a major-league team. This time the New York Yankees started their spring training on the island, as part of a Caribbean swing that also included Venezuela and Cuba. Again Larry MacPhail was responsible; by this point he was president of the Yankees (Charlie Dressen was one of the team’s coaches as well). The sponsor was Don Q Rum, the leading Puerto Rican brand whose name adorned Escobar’s big scoreboard.

The Bronx Bombers played five games in Puerto Rico against all-star teams and won three of them. All the games (as well as practice sessions) took place in Escobar. During that trip, Joe DiMaggio was still recovering from an operation on his heel; the incision had become badly infected. Nonetheless, he insisted on accompanying his team. The Yankees were staying in the Normandie Hotel, the noted art deco structure across the street from Escobar. Even for that short a distance, DiMaggio “could only drag himself to the ballpark,” and because he was “besieged by excited fans,” he needed a police escort.30

Later that year, Escobar’s political atmosphere reached fever pitch. As far back as 1919, an independence movement had formed in Puerto Rico. One of its leading figures was Pedro Albizu Campos, a Harvard-educated attorney. In December 1947, Albizu returned to Puerto Rico after 11 years in the United States (for much of that time he was either in prison or the hospital). On December 15, he addressed a standing-room-only crowd of 14,000 at Escobar. As author Nelson Denis described it, “For over an hour he thundered about independence. The stadium shook as the crowd members stomped and chanted and cheered and pumped their fists in the air.”31

Meanwhile, during the PRWL’s 1947-48 season, Willard Brown was at his best. Brown felt that he had something to prove after that summer, in which he’d gotten what proved to be his one opportunity in the majors, a disappointing one-month stint. It may have been that winter when sportswriter Rafael Pont Flores coined Brown’s nickname Ese Hombre (“That Man”). Brown won the Triple Crown with staggering statistics: .432-27-86 in just 60 games. Of his 27 homers, 22 came at Escobar.

Another of the PRWL’s all-time stars began his career in the island with Santurce in 1947-48. That was Bob Thurman, who earned the nickname El Múcaro (“The Owl”) because of his performance in night games. In 11 seasons as a Crabber, Thurman hit 117 home runs. He finished with 120 in Puerto Rico, topping the league’s career list. According to Puerto Rican author Edgardo Rodríguez Juliá, Thurman was also known for his remarkably long foul balls – one of which supposedly struck a solitary crocodile in Muñoz Rivera Park.32

On March 12, 1948, a big-league club played at Escobar again. This time it was the Brooklyn Dodgers, with Jackie Robinson, who beat a Puerto Rican all-star team, 5-2. Actress Laraine Day, then married to Dodgers manager Leo Durocher, threw out the first ball.33

Sixto Escobar Stadium remained a crucible of Puerto Rican politics. The island’s independence movement had prompted the formation of another party, the Puerto Rican Independence Party (PIP), in 1946. During its first General Assembly, on July 25, 1948, some 20,000 people were said to have been present at Escobar.34

Willard Brown had another big season for Santurce in 1948-49, and Tito Stevens remembered a funny episode. “My dad took me to one of many games and we sat in the box over the Santurce first-base dugout. Box seat holders had to present their ticket to a person at a door in the lobby area under the grandstand and be given a folding chair they then took to the box. While there, I started playing with a Coke bottle with my foot and it started rolling over the dugout roof. Just as Willard Brown stepped out to the on-deck circle, the bottle fell at his feet. ‘Who threw that @#$%ing bottle at me?’ shouted Brown. I explained what had happened and he smiled and said, ‘OK, kid. I’ll hit a home run for you.’ Well, true to his word, Brown blasted one of his 18 homers that season.”35

The Caribbean Series, which pitted the region’s winter-league champions against each other in a round-robin tournament, started in 1949. In the first era of the series, which ran through 1960, Escobar hosted the event three times: in 1950, 1954, and 1958. In 1950, Puerto Rico (represented by the Caguas Criollos) came in second behind the upset winner, Panama’s Carta Vieja Yankees. The most exciting moment for the home crowd came on February 23. Venezuela’s Magallanes Navigators took a 1-0 lead into the bottom of the ninth, but Caguas pinch-hitter Wilmer Fields – called in from the coaching lines – hit a two-run homer.36

A separate movement in Puerto Rican politics at the time focused on statehood for the island. On August 19-20, 1950, a special assembly of the Statehood Party was held at Escobar to settle the question of the party’s position toward Law 600 of 1950. That law authorized Puerto Ricans to enact their own Constitution, subject to approval by the U.S. President and Congress. According to author Robert William Anderson, the assembly “was marked by fistfights and catcalls.”37

It should not be forgotten how deadly serious many Puerto Rican nationalists were at that time. Two of them, Óscar Collazo and Griselio Torresola, sought to assassinate President Harry S Truman on November 1, 1950. Secret Service agents killed Torresola during the attempt; inside Torresola’s jacket was found a letter from Pedro Albizu.

The biggest baseball crowd ever at Escobar was 16,713, on February 17, 1951. It was the seventh game of the PRWL finals between Santurce and Caguas. A two-out home run in the bottom of the ninth by José St. Clair, better known as Pepe Lucas, gave the Crabbers their first league title. The Dominican’s blow went down in history as the Pepelucazo. The crowd – which had started filing into the stadium at 7 A.M. – “hoisted their heroes to their shoulders for a parade through the streets of Santurce. . .an all-night demonstration was staged.”38

One of the most momentous baseball events at Escobar was not a game. It was the tryout in 1952 that brought Roberto Clemente to the attention of the major leagues. Pedrín Zorrilla, owner of the Crabbers, and the Brooklyn Dodgers organized the clinic. The teenaged Clemente made a powerful impression on Brooklyn scout Al Campanis. Eventually, in early 1954, Clemente signed with the Dodgers – but his pro career began for Santurce in the 1952-53 season.

In the winters of 1952, 1953, and 1954, something unusual was visible on the field at Escobar: snow. The mayor of San Juan, Felisa Rincón de Gautier, had become friends with Eddie Rickenbacker, the World War I flying ace who had become chairman of Eastern Airlines. Planeloads of the white stuff were flown down from New England so that Puerto Rican children could enjoy playing in it – though it melted very quickly – as a treat for the major Latin American holiday, Three Kings’ Day. Doña Fela (as the mayor was known) also viewed it as an educational experience for the kids.

In February 1954, Puerto Rico (again represented by Caguas) won the Caribbean Series for the only time in the three times it was held at Escobar. The team was led by series MVP “Jungle Jim” Rivera. After the victory, player-manager Mickey Owen rode through the stadium on a filly – yegüita in Spanish, the longtime symbol of the Caguas club. Owen, his steed, and the joyful Puerto Rican in front were all wearing straw hats.

The 1954-55 Crabbers were indeed a potent team. In addition to Clemente, the lineup boasted Willie Mays and George Crowe; Bob Thurman was also still with the club, hitting and occasionally pitching – his play finally got him to the majors in 1955, at the age of 37. The staff was led by Sam Jones, who won the Triple Crown of pitching, Rubén Gómez, and Bill Greason.

The Caribbean Series returned to Escobar in 1958. That year victory went to Cuba and its champion, the Marianao Tigres. Puerto Rico finished tied for second at 3-3. Vic Power and Clemente were the home team’s leading batters. On February 8, Juan Pizarro fired 17 strikeouts in an 8-0, two-hit win over Panama, shattering the tournament record. A big turning point in the series came two days later, with Pizarro on as a fireman in the ninth inning. The bases were loaded with nobody out, and the tying run would have scored anyway on a long fly to right field, but when an umpire ruled that the ball had been dropped, the irate crowd at Escobar started “a small-scale riot.” The game was suspended and completed the following night.39

Also during that tournament, syndicated columnist Red Smith depicted Escobar and one of its salient features for the benefit of U.S. newspaper readers. In a passage called “Baseball, Southern Fried”, he wrote, “In Sixto Escobar Stadium the scoreboard plugs Don Q rum instead of Ballantine’s or Schaefer’s or Chesterfield, and outlined against the sky beyond right field are palm trees instead of the steelwork of the East Side subway. Otherwise this could be a small Yankee Stadium or Polo Grounds gone daft.”

Smith continued, “These are twi-night doubleheaders; they start at 6:30 p.m. after dark has fallen and go on to the edge of endurance. Around midnight the fans are still there, maybe 15,000 of them, which is all the park can hold, though their voices have left them innings earlier. Apparently San Juan neither dines nor sleeps during the series.”40

Sixto Escobar Stadium also hosted American football on occasion. Tito Stevens said, “I witnessed a couple of football games there in 1958 when the Antilles Command team played. One of the teams they faced – and by the way, they were wiped out by them –was the team from Mitchel Air Force Base on Long Island. The Antilles team was made up of MPs from Fort San Cristóbal and personnel from Fort Buchanan.”41

In late 1958, the Continental League – the would-be third major league – germinated as an idea. On July 27, 1959, the league was formally announced. Bill Shea, the prime mover, listed five founding franchises and 11 cities that had showed interest in joining. One of them was San Juan.42 The following month, though, it was turned down because its population and Escobar’s capacity were deemed inadequate. That same story also noted that Escobar had hosted the Latin American Little League Baseball championship. Puerto Rico beat Venezuela and advanced to the Little League World Series, the first team from the island to do so.43

On April 1-3, 1960, the Philadelphia Phillies and the defending American League pennant winner, the Chicago White Sox, played a three-game exhibition series at Escobar. Originally, there were plans to go to Caracas, Venezuela before San Juan, but that leg of the trip did not happen.44 Alas, attendance was poor (just 8,834 total), despite much advance PR work. Those who made it were treated to the entertainment of Jim Rivera, who joined the Navy band and did calypso dances. However, players complained about the travel time, “Class C” lighting, and uneven, concrete-hard infield.45

The Senators won the PRWL championship in the 1960-61 season, beating Caguas in the playoffs, five games to three. One memorable moment came in Game One, when the enormously powerful Frank Howard hit a home run that an engineer measured at 536 feet, giving Caguas a 2-1 win.46 Depending on one’s view regarding Josh Gibson’s shot in March 1942, Howard’s homer ranks as the longest in PRWL history.47 The opposing pitcher, Jack Fisher, told Lou Hernández, “Frank hit it over two centerfield fences, over some logs and barrels and out on the beach. . .I sure remember that one.”48

Sixto Escobar Stadium briefly hosted Triple-A ball in 1961. Ahead of that season, the Miami Marlins of the International League were transferred to San Juan. They played at Escobar, which was spruced up (capacity was listed at just 9,400). Meanwhile, San Juan’s new ballpark – Hiram Bithorn Stadium – was under construction. The Marlins’ roster included three Puerto Ricans: Julio Gotay, Ed Olivares, and player-coach Reynaldo Oliver.

Despite high hopes, however, the Marlins’ attendance in San Juan was poor – an average of just 1,000 a game for the first 12 home dates after the opener, which drew 6,627. IL president Tommy Richardson said that the Cuban crisis had caused an economic squeeze in Puerto Rico, making admission unaffordable for most people. As a result, visiting clubs’ share of the gate receipts was not enough to meet the costs of travel to San Juan.49 Yet even a children’s night, in which kids got in free, could not get the turnstiles spinning.50 Contrary to Richardson’s theory, the locals may simply have preferred homegrown players. On May 17, 1961 – even though the team was only half a game out of first place – the Marlins announced that they were moving to Charleston, West Virginia.51

The PRWL’s final regular-season game at Escobar took place on January 23, 1962. It was a one-game tiebreaker between San Juan and Arecibo to decide which team would get the fourth and final spot in the playoffs. Roberto Clemente did not play for much of the season, but after he joined San Juan, the Senators won 18 of their last 24 games to draw even with the Wolves. Arecibo won the tiebreaker, though, by a score of 7-5. The game featured a big rhubarb in the second inning when Clemente was called out at first with the bases loaded and the score tied 3-3. Police had to break up the fistfight between San Juan manager Napoleón Reyes and umpire Mel Steiner.52

Santurce won the playoffs, and the last professional ballgames of any kind held at Escobar took place shortly thereafter. They came during the Inter-American Series, another intra-regional tournament held for four years starting in 1961. (Cuba’s withdrawal ended the first era of the Caribbean Series after the 1960 edition.) Puerto Rico, represented in part by the Crabbers, won in 1962, led by two wins from Bob Gibson and four home runs by Mike de la Hoz. The fourth of the Cuban infielder’s homers – and the last at Escobar – came on Valentine’s Day 1962. It was a game-winner in the bottom of the 11th inning against his countryman Luis Tiant, pitching for Mayagüez, the other Puerto Rican entry in the series.53

Hiram Bithorn Stadium opened in October 1962. However, lower-level baseball was played at Escobar after that. Tom Van Hyning, who lived much of his early life in Puerto Rico, said, “I had a Pony League tryout at Sixto Escobar Stadium in 1967. It was used for youth baseball and I recall the seating was in need of repairs and renovations.” Van Hyning also noted that Escobar served as the home field for the eight-man American football team of Santurce’s Robinson School from 1963 through 1969.54

Basketball is also a popular sport in Puerto Rico. For many years, Escobar hosted various teams in the island’s top hoops league, BSN (Baloncesto Superior Nacional). They included another club named the Santurce Crabbers – which is actually older than the baseball team – the Rio Piedras Cardinals, and the San Juan Saints.55 BSN competition shifted to Bithorn Stadium in 1963.

In addition, notable track and field competition has taken place at Escobar:

- Many events of the 1979 Pan American Games were held there, after extensive renovations – it was then that Escobar’s baseball configuration was removed.

- In September 1985, trials took place to select the Americas team for the fourth World Cup in Athletics.

- On July 29, 1989, at the Caribbean amateur athletic championships, the great Cuban athlete Javier Sotomayor became the first human to clear eight feet in the high jump. His coach said that conditions at the stadium were “marvelous for the jump.”56

In early 2011, further repairs and improvements on Sixto Escobar Stadium were completed in order to welcome a new tenant from a different sport: soccer. The new home team was Club Atlético River Plate Puerto Rico, a franchise in the Puerto Rico Soccer League.57

The Museum and Library of the Hall of Fame of Puerto Rican Sports was located in Sixto Escobar Park on March 18, 2010. In August 2014, the structure was declared a National Historic Monument. To celebrate the first anniversary of this status, the U.S. Postal Service issued a commemorative stamp.

Sixto Escobar Stadium’s lifespan as a professional baseball venue was less than three decades. It became antiquated rather rapidly. Yet while it flowered, it was as pretty and quaint and lively a place to watch a game as one could imagine.

Originally posted in February 2016. Updated in February 2017.

Acknowledgments

With continued thanks to SABR colleagues Jorge Colón Delgado, Tom Van Hyning, Lou Hernández, and Tito Stevens for their input.

Images courtesy of Jorge Colón Delgado’s collection.

Additional sources

José A. Crescioni Benítez, El Béisbol Profesional Boricua, San Juan, Puerto Rico: Aurora Comunicación Integral, Inc., 1997.

Notes

1 “Parque Sixto Escobar, Monumento Histórico Nacional” official proclamation, August 5, 2014 (http://pr.microjuris.com/ConnectorPanel/ImagenServlet?reference=/images/file/L_130_14.pdf)

2 Thomas E. Van Hyning, The Santurce Crabbers: Sixty Seasons of Puerto Rican Winter League Baseball, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 1999: 1.

3 Thomas E. Van Hyning, Puerto Rico’s Winter League: A History of Major League Baseball’s Launching Pad, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 1995: 11, 47. Van Hyning, The Santurce Crabbers, 9-10.

4 Van Hyning, The Santurce Crabbers, 10.

5 Van Hyning, Puerto Rico’s Winter League, 57. Lou Hernández, Memories of Winter Ball, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2013: 197.

6 Hernández, Memories of Winter Ball, 171, 166, 189.

7 E-mail from Tito Stevens to Rory Costello, February 15, 2017 (hereafter Stevens e-mail).

8 Michael M. Oleksak and Mary Adams Oleksak, Béisbol: Latin Americans and the Grand Old Game, Grand rapids, Michigan: Masters Press, 1991: 62.

9 “Parque Sixto Escobar, Monumento Histórico Nacional”

10 Carlos Uriarte González, “Los 80 años del Estadio Sixto Escobar”, El Nuevo Día (San Juan, Puerto Rico), November 8, 2012

11 Letter excerpt quoted in William McNeil, Black Baseball Out of Season, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2007: 114.

12 Johnny Torres Rivera, “Estadio Sixto Escobar”, Puerta de Tierra website (http://www.puertadetierra.info/edificios/escobar/escobar.htm)

13 Jane Allen Quevedo, “Hiram Bithorn”, SABR BioProject.

14 “Reds to Visit Puerto Rico”, Associated Press, January 9, 1936.

15 “Cincinnati’s Redlegs Head to Puerto Rico”, Virgin Islands Daily News, February 17, 1936, 1.

16 Ronald T. Waldo, Hazen “Kiki” Cuyler, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2012: 200.

17 Waldo, Hazen “Kiki” Cuyler, 200. Tom Swope, “Dressen Puts Hobbles on Reds, Fearing Squad Will Go Stale”, The Sporting News, February 20, 1936, 1. “Exhibition Games”, The Sporting News, March 5, 1936, 2.

18 Allen Quevedo, “Hiram Bithorn”

19 Fernando Corneiro, “With the Cincinnati Reds”, Virgin Islands Daily News, March 3, 1936, 1. Corneiro played a vital role in the history of baseball in the Virgin Islands, as may be seen in the story of Joe Christopher.

20 “Sixto Escobar Retains Title”, United Press, February 22, 1937.

21 “Jeffra, Escobar to Meet Sunday in Title Battle”, Associated Press, February 14, 1938.

22 Eddie Brietz, “Sports Roundup”, Associated Press, September 8, 1939.

23 Van Hyning, Puerto Rico’s Winter League, 233, via El Mundo (San Juan, Puerto Rico), September 6, 1939. Coimbre played for Ponce in the regular season; he joined Guayama as a reinforcement for the series against Duncan (a common practice in winter-league postseason competition).

24 Van Hyning, The Santurce Crabbers, 10.

25 Van Hyning, Puerto Rico’s Winter League, 233.

26 “Oklahoma Nine Wins Semi-Pro Title”, Associated Press, October 2, 1940.

27 Van Hyning, The Santurce Crabbers, 16.

28 Hernandez, Memories of Winter Ball, 208.

29 Rafael Costas, Enciclopedia Béisbol Ponce Leones, 1938-87, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic: Editora Corripio, 1989: 84.

30 Richard Ben Cramer, Joe DiMaggio: The Hero’s Life, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2000: 226.

31 Nelson A. Denis, War Against All Puerto Ricans, New York: Nation Books, 2015.

32 Edgardo Rodríguez Juliá, San Juan: Memoir of a City, Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press, 2007: 65.

33 The Sporting News, March 24, 1948, 22.

34 Robert William Anderson, Party Politics in Puerto Rico, Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 1965: 133.

35 Stevens e-mail. Brown and Bob Thurman tied for the league lead in homers that season.

36 Santiago Llorens, “Panama Wins the Caribbean Pennant in Special Playoff”, The Sporting News, March 8, 1950, 25.

37 Anderson, Party Politics in Puerto Rico, 85.

38 Santiago Llorens, “16,713 See Homer Clinch Playoff Title for Santurce”, The Sporting News, February 28, 1951, 25.

39 “Latin Tempers Explode,” “Ump’s Ruling Provokes Fan Riot; Series Game Halted”, The Sporting News, February 19, 1958, 30.

40 Red Smith, “Views of Sport”, syndicated column, February 11, 1958.

41 Stevens e-mail.

42 “Continental League Plans to Be in Operation by ‘61”, Associated Press, July 28, 1959.

43 “Veto San Juan as Team in New Major League”, Virgin Islands Daily News, August 24, 1959, 1.

44 Jerry Holtzman, “Pale Hose, Phils Complete Plans for Latin Junket”, The Sporting News, February 3, 1960, 9.

45 Jerry Holtzman, “Pale Hose-Philly Puerto Rico Trip 10-G Flopperoo”, The Sporting News, April 13, 1960, 11.

46 Miguel J. Frau, “Stock, Fisher Hurl Gems in San Juan’s Drive to Loop Flag”, The Sporting News, February 15, 1961, 17.

47 Van Hyning, Puerto Rico’s Winter League, 15.

48 Hernández, Memories of Winter Ball, 170.

49 “Marlins Will Quit San Juan”, Associated Press, May 4, 1961. “San Juan ‘Move’ Talk Hit”, Associated Press, May 5, 1961.

50 “Moford Blanks Marlins for 1-0 Victory”, Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, April 29, 1961, 24.

51 “Charleston Gets San Juan Club”, Associated Press, May 18, 1961.

52 Van Hyning, Puerto Rico’s Winter League, 64. Miguel J. Frau, “Cepeda Sparks Wallopers to Record HR Total of 271”, The Sporting News, January 31, 1962, 31.

53 Miguel J. Frau, “Crabbers Cop Latin Title Fourth Time in 14 Years”, The Sporting News, February 21, 1962, 37-38.

54 E-mails from Tom Van Hyning to Rory Costello, January 27 and January 28, 2016.

55 Uriarte González, “Los 80 años del Estadio Sixto Escobar”

56 Luis R. Varela, “Sotomayor first to high jump 8 feet”, Associated Press, July 31, 1989. Even in 2016, Sotomayor remains the only person in history to clear eight feet. His record, which has endured since 1993, is just short of 8 feet, 0.5 inches.

57 “Petter Villegas se une al River Plate PR”, El Nuevo Día, August 24, 2010.