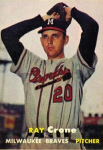

Ray Crone

“Amazing,” said Ray Crone when asked by the author to describe fan support in Milwaukee in the 1950s.[1] A tall, lanky right-handed pitching prodigy signed by the Braves in 1949, Crone debuted in 1954 and pitched a ten-inning complete game in his first start in the major leagues. However, after four inconsistent seasons and a 25-20 record with the Braves from 1954 to 1957, Crone was sent to the New York Giants at the trading deadline in 1957 in exchange for Red Schoendienst, thus missing the Braves’ historic World Series championship.

“Amazing,” said Ray Crone when asked by the author to describe fan support in Milwaukee in the 1950s.[1] A tall, lanky right-handed pitching prodigy signed by the Braves in 1949, Crone debuted in 1954 and pitched a ten-inning complete game in his first start in the major leagues. However, after four inconsistent seasons and a 25-20 record with the Braves from 1954 to 1957, Crone was sent to the New York Giants at the trading deadline in 1957 in exchange for Red Schoendienst, thus missing the Braves’ historic World Series championship.

On August 7, 1931, Raymond Hayes Crone was born to Gordon and Annie (Gunti) Crone in Memphis, Tennessee. The fifth of six children, Ray was introduced to baseball by his father, who worked for Goodyear and played in a Sunday-morning league for men over 35. In grade school he began to play shortstop and pitch on teams sponsored by the Kiwanis Club and other service organizations. “Halfway through my first year in high school in 1946,” Crone said of his high-school freshman team, coached by Hall of Famer Bill Terry, “they promoted me to the varsity team.” Over the next three years at Christian Brothers High School and in American Legion ball in the summer, Crone established his reputation as one of the best pitchers Memphis ever produced. Pitching for Lew Chandler, who coached both teams, he led his American Legion team, sponsored by Corbitt Motors, to three consecutive state championships. As a 15-year-old he pitched the title game of the American Legion regional in North Carolina. It ran 18 innings and Crone no-hit the opposition from the sixth through the 16th inning, but lost. “Lew would be put in prison nowadays for abusing kids,” Crone joked.

“I never played other positions,” said Crone, who threw five no-hitters as a prep phenom. “I pitched and batted ninth.” Scouts from the Cardinals, Red Sox, Tigers, and Braves attended his games. “I signed with Bill Maughn of the Boston Braves one day after I graduated high school in 1949, because he was more positive about my career and chances.” He was assigned to the Owensboro Oilers in the Class D Kentucky-Illinois-Tennessee (Kitty) League in 1949. Traveling and playing so many games in American Legion baseball prepared him for the physical demands of Organized Baseball and the emotional demands of being away from home for a 17-year-old, he said. “I was calm and remember no anxiety about facing anybody.” The youngest player of the team, Crone won nine games, lost three, and posted a 2.93 ERA. He did not attribute his success to any specific coach.[2] “Back then baseball got all the best athletes,” Crone said. “There were more than 50 minor leagues. The organization just threw the balls and bats out there and you played. I learned to play by watching semipro games in Memphis.”

After Crone’s successful seasons with the Evansville Braves in the Class B Illinois-Indiana-Iowa (Three-Eye) League in 1950 and with the Hartford Chiefs in the Class A Eastern League in 1951, where he won 11 and 12 games respectively, the 6-foot-2, 165-pound right-hander was assigned to the Double-A Atlanta Crackers. “In 1952 I went to spring training with Atlanta and Dixie Walker was the manager. We trained in Pensacola, Florida. I made the team and was the opening day pitcher,” Crone said. “But I began to lose it. I was just throwing the ball.” Having pitched just 19 innings and accumulated a 9.00 ERA, Crone was reassigned to Hartford, where he won 12 games again. Pleased with his development, the Braves signed him to a major-league contract at the conclusion of the season.

In 1953 the 21-year-old Crone was invited to his first spring training with the Braves in Bradenton, Florida. With 45 minor-league wins under his belt, Crone was confident in his abilities. “I thought I threw strikes and had good control when I got to spring training. But from watching guys like Vern Bickford, Warren Spahn, and Lew Burdette, I noticed that certain counts, 3-2 or 2-2, they didn’t give in and hit the corners. They threw quality strikes. That made me a better pitcher because I realized what big leaguers did.” During the last two weeks of spring training, the Braves, who had just announced their move from Boston to Milwaukee in March, visited their minor-league affiliates. When they arrived in Atlanta, Crone remained there, having been optioned to the Crackers. “I hooked up with Art Fowler and he taught me the slider,” Crone said. Despite learning a new pitch, Crone’s days in Atlanta were also frustrating. “Gene Mauch was the manager. I was there for about two weeks and he pitched me about four innings in spring training. We were about to start the season and Mauch told me that I am being sent to Jacksonville.”

Having trained with major leaguers, Crone was disappointed to be assigned to Class A ball and had serious concerns about his future and even pondered quitting. “The demotion made me upset because I had been in A ball for a couple of years,” he said. “You don’t have many options to fight the decision. But I was determined and had the only great year I ever had and the slider helped.” With a league-high 19 wins to accompany his 2.38 ERA in 253 innings pitched (all career bests), Crone and 19-year-old second baseman Hank Aaron led the Jacksonville Braves to the best regular-season record in the South Atlantic (Sally) League. He won two more games in the playoffs, including a 14-inning complete-game masterpiece over the Savannah Indians, but the Braves lost the league championship.[3]

In preparation for another shot at the big leagues, Crone, along with future Braves teammates Aaron, Bob Buhl, and Felix Mantilla, played for Caguas in the Puerto Rican Winter League in 1954 and led them to the league title. Crone had a 6-1 record in the second half of the season. “At the time I was eager to play anywhere and see the world,” Crone said. He credited his success to player-manager Mickey Owen, a former catcher with the Brooklyn Dodgers. “I never pitched to a better catcher than Owen. He really helped me. Not just with words, but with the way he handled me.”

After his most successful year pitching, Crone began his second spring training with the Braves in 1954 with more than 60 career wins in Organized Baseball and confidence in his curveball, slider, and control. “I had a changeup,” Crone said, “but in those days you didn’t throw a changeup much like today.” He earned a spot on the team and made his major-league debut in the first game of the year, pitching two-thirds of an inning of scoreless relief against the Cincinnati Reds in a 9-8 loss.

He immediately noticed the difference between the majors and minors. “It made an impression on me in the first game when our manager, Charlie Grimm, got upset because Cincinnati had scored an early run. In the minor leagues, when teams got a run or two, that was no big deal.” On May 23 in Chicago Crone notched his first major-league victory by pitching a ten-inning complete game. With two outs in the ninth inning of a scoreless game, Crone lined a single scoring Joe Adcock for his first career RBI; Aaron also scored on a throwing error by right fielder Frank Baumholtz. Up 2-0 with two outs in the bottom of the ninth inning, “Ernie Banks hit one in the seats to tie the game. I threw him a slider, up and away.” Crone recalled that it was taken for granted that he would pitch the tenth inning. “No one said anything or asked me how I was doing.” After the Braves scored two runs in the extra frame, Crone gave up a two-out single and walk before striking out Gene Baker to earn his first win.

In late July, with only limited relief action after his impressive win, Crone was optioned to the Toledo Sox of the Triple-A American Association, where he won seven of ten decisions and posted a 3.00 ERA. On August 20 against the St. Paul Saints, he pitched a seven-inning no-hitter in the first game of a doubleheader. He was recalled to Milwaukee in mid-September, had three relief appearances, and then ended the season with a start against the Cardinals and pitched nine innings of shutout ball before being replaced by Ernie Johnson. After he finished with a 1-0 record and a 2.02 ERA in 49 innings, Crone’s future appeared bright on the third-place Braves, who led the National League in attendance and became the first team in the senior circuit to draw over 2 million fans.

With Warren Spahn, Lew Burdette, Bob Buhl, and Gene Conley, the Braves had one of the strongest pitching rotations in baseball to start spring training in 1955; nonetheless The Sporting News reported that Crone had an excellent chance of winning a starting job.[4] No longer bothered by nagging arm injuries, Crone was tabbed as the team’s fifth starter. But after giving up three home runs and lasting just 3⅓ innings in his initial start, he was relegated to the bullpen, where he continued to struggle, and was soon optioned to Toledo again with an unsightly 10.12 ERA in five appearances. At Toledo he pitched spectacularly beginning with a shutout over the Louisville Colonels with Braves owner Louis Perini and general manager John Quinn in attendance. After pitching four consecutive complete-game victories and giving up just 23 hits and three runs (0.75 ERA) during the best stretch of his career, he was recalled to the Braves.[5]

Crone “has excellent stuff” wrote Braves’ beat writer Red Thisted during a stretch in which the 23-year-old right-hander gave up just two earned runs in 14 innings in June to earn another shot in the starting rotation.[6] He completed 6 of 13 starts in the second half of the season, including his only career shutout on September 5 when he threw a three-hitter against the Cubs in Chicago. He finished the season with a 10-9 record and 3.46 ERA in 140⅓ innings for the second-place Braves.

In the 1955 offseason, Ray married Joan Anne Carroll, whom he met while playing in Hartford. Like many of the Braves players, Ray lived in Milwaukee year-round and served as a representative for a local brewery in the offseason.[7] “Ray has control [and] knows how to pitch,” said new Braves pitching coach Charlie Root, who replaced Bucky Harris to start the 1956 season. He predicted that Crone might win 15 games.[8] With a poor spring and an ERA over 5.00, Crone competed for the fourth starting position with Red Murff, a 35-year-old “rookie,” who was coming off a 27-win season in the Double-A Texas League. Murff was given the job, but surrendered five runs in five innings in his only start of the season. Due to a quirky schedule and canceled games, Crone made his first start in game six of the season and pitched a complete-game victory over the Cardinals. Manager Charlie Grimm’s Big Three, Spahn, Burdette, and Buhl, started the next eight games before Crone got his second start. Not only did he pitch another complete-game victory, he also executed the first successful suicide squeeze bunt for the Braves since they moved to Milwaukee, knocking in Wes Covington, and also scored two runs in his most productive game at the plate.[9]

On May 26 against the Reds in Milwaukee, Crone was involved in one of the strangest and most memorable games of the season. Leading 1-0 through seven innings, he was locked in a pitchers’ duel with notoriously wild Johnny Klippstein, who was working on a no-hitter despite issuing seven bases on balls, hitting one batter, and surrendering one run. Reds manager Birdie Tebbetts pinch-hit for Klippstein in the eighth inning, after which Hersh Freeman and Joe Black held the Braves hitless in the eighth and ninth innings, thus completing an unprecedented three-man no-hitter through nine innings. (The MLB Committee on Statistical Accuracy changed the definition of a no-hitter in 1991, thus removing this game from the list of no-hitters.) Crone gave up a two-out game-tying double to Wally Post in the ninth inning and the game finally ended in the 11th inning when Black surrendered a run-scoring single to Frank Torre, giving Crone a complete-game, extra-inning victory.

The 11-inning outing was the longest in Crone’s major-league career. “Managers watched pitchers,” he said. “When pitchers started to tire, they finished their motion poorly and started throwing high.” Three decades before pitch counts dictated how many innings a pitcher could throw, Crone expected to pitch deep into ballgames and confessed that he did not worry about his arm. “The worst thing that happened to pitching was the radar gun,” he lamented. “When I pitched no one knew about velocity; they just said, ‘He threw hard.’ You pitched at your capability. Your arm and your control dictated how you could throw.” Never a “hard thrower,” Crone relied on his control and threw to all corners of the plate.

After their slow start to the season which resulted in Grimm being replaced by Fred Haney, the Braves were in first place, 2½ games ahead of the Dodgers entering September. Having lost his spot in the starting rotation after a string of several ineffective starts in late July and August and pitching out of the bullpen for the last month of the season, Crone resurrected his season and boasted a 1.69 ERA in 21⅓ innings over 11 appearances in September; however, the Braves struggled mightily and fell into second place. With the team heading into the final three-game series of the season against the Cardinals and in first place by a half-game, Crone was confident the Braves would win the pennant. “We went into St. Louis with the lead and my roommate Chuck Tanner and I joked that we were going to buy our wives fur coats.” The Braves lost two of three while the Dodgers swept the Pirates to win the NL pennant in dramatic fashion.

The stunning loss was traumatic for the Braves and their fans. “One thing I criticize Haney for is he started his Big Three too much at the end of the season,” Crone said. Spahn, Burdette, and Buhl started 15 of the team’s last 17 games and the final ten. “Burdette and Buhl did not pitch well down the stretch. Haney could have pitched somebody different, but played it safe,” Crone opined. Both Buhl and Burdette had their worst months of the season, winning just twice each with 6.39 and 4.46 ERAs respectively. Though he finished with career highs in wins (11) and innings pitched (169⅔), Crone suggested that Haney lacked confidence in him. Almost immediately after the conclusion of the season, rumors of a trade began to swirl involving Crone and longtime Cardinals second baseman Red Schoendienst, who had been traded to the New York Giants during the 1956 season.[10]

Crone began the 1957 season in the starting rotation and won his first start of the season, surrendering four runs in 7⅔ innings against the Reds in the third game of the season. But after an ineffective second start, he again lost his spot in the starting rotation. General manager John Quinn continually denied rumors of an imminent trade between the New York Giants and the Braves involving Crone, pitchers Gene Conley, Don McMahon, Juan Pizarro, or outfielder Wes Covington. After two rough relief outings, Crone found himself lost in the Braves’ bullpen. Manager Haney juggled his pitching rotation so that left-hander Warren Spahn did not have to pitch against the Dodgers at Ebbets Field with its short right field and gave Crone a spot start on June 11. Crone took advantage and hurled a complete-game victory that proved to be his last win as a member of the Milwaukee Braves. Four days later he was traded along with Danny O’Connell and Bobby Thomson to the Giants for the 34-year old Schoendienst.

“I was disappointed about the trade,” Crone said. “We were in Philadelphia at the time. I remembered seeing something in my hotel mailbox. We were at the trading deadline. O’Connell, Thomson, and I took the train to New York.” Crone didn’t want to leave the only organization he knew. He lived in Milwaukee year-round with his family, and felt at home in the city. After he was chased in the second inning of his Giants debut in the Polo Grounds on June 16, New York fans voiced their displeasure with the trade. Crone exacted revenge against his former club in his next outing when he relieved Johnny Antonelli and pitched six innings of three-hit shutout ball against Spahn and the Braves to earn his first victory as a Giant. His success was short-lived; he lost his next five decisions as a starter before beating the Phillies in New York on August 9 in the last complete game of his major-league career.

“I didn’t respond to the trade well,” said Crone of leaving the Braves in their magical championship season. “After the Braves I never felt comfortable.” A quiet and mild-mannered person, Ray kept to himself and never sought the bright lights of stardom. After playing with the “down-home” and relaxed Braves, he felt alienated by Giants manager Bill Rigney and his loud and sometimes self-serving personality. “Rigney was a version of Leo Durocher and was not that enamored with me.” He finished with a combined record of 7-9 (4-8 with the Giants) and a 4.36 ERA in 163 innings, Crone’s season was erratic and unpredictable; nonetheless Giants vice president Chub Feeney expressed his confidence in the 26-year-old , healthy pitcher, saying, “We still think Crone can be a very big winner for us in the future.”[11] Crone played on the last Giants team in New York and on the first in San Francisco. “The fans were excited out there,” he remembered. “They had a big banquet and a parade for us.” Despite the city’s enthusiasm for major-league baseball, Crone thought that the sportswriters and news media were relatively uninformed about the team, other than its star players like Willie Mays and Johnny Antonelli, and consequently may not have been as critical of the team, which had come off a miserable 69-85 season in 1957. Playing in Seals Stadium, so named for the San Francisco Seals of the Pacific Coast League, Crone recalled, “You’d sit in the bullpen and freeze.”

Beginning the 1958 season in the bullpen for the Giants, Crone threw four innings of one-run relief on April 24 to earn his first victory of the season and the last in his major-league career. Seeing mainly mop-up duty for the next seven weeks (he appeared in ten consecutive Giants losses), Crone was traded to the Triple-A Toronto Maple Leafs on July 15 for 31-year-old former major leaguer Don Johnson, an inconsistent pitcher with immense potential. Crone languished in Toronto, going winless in two decisions, and never made it back to the major leagues.

Crone admitted that he was affected by the pressure to succeed and pitch consistently well. “In my mind I wasn’t doing so well,” Crone explained how he thought as a major-league pitcher. “All through my career, I always wanted to do well. When I went to pro ball, I was determined to do well. When I was young, I saw guys who were signed come home with failure and I didn’t want to do that. I wanted to make my family proud.” Though he never suffered a debilitating injury or a weak or tired arm, after his trade to the Giants Crone never recaptured the fleeting moments of excellence he had with the Braves. He finished his five-year major-league career with 30 wins, an equal number of losses, and a 3.87 ERA in 546 innings.

Despite his poor 1958 season, Crone was determined to make it back to the big leagues and decided to play winter ball with Oriente in the Venezuelan League in 1958-59.[12] He started the 1959 season with Toronto, a franchise owned by Jack Kent Cooke, who specialized in acquiring former major-league players, resurrecting their careers in the International League, and then selling them back to a major-league team. “We opened up in Havana, Cuba,” Crone said. “Castro was taking over at the time. There were kids with machine guns near the dugout. The game was held up until Castro arrived.” Struggling to regain his form and winless in two decisions, Crone was sold conditionally to the Double-A Birmingham Barons, and began a frustrating odyssey that led him to five teams through 1961. Returned to Toronto after two ineffective starts, he was sold to the Double-A Chickasaws in his home town of Memphis, where he went 6-10 with a respectable 3.19 ERA in 110 innings pitched.“

By 1960 my heart was not in it anymore,” Crone said. “I didn’t have many options [for a different career] and no college background. I was sold and traded without my control.” He felt exploited by teams that viewed him as personal property to be traded or sold for profit without considering how a trade might affect his life, family, and children. Within a span of a year (from late 1959 through the 1960 season), Crone had the unenviable distinction of being the property of, and being sold by, teams in each of the three Triple-A leagues, going from Charleston in the American Association to Portland in the Pacific Coast League, and finally to Dallas-Fort Worth in the American Association. He compiled a 5-12 cumulative record.

Astonished to learn that he was again the property of the Toronto Maple Leafs, Crone reported to their spring training in 1961. Released before the beginning of the season, he signed with the Jacksonville Jets, the expansion Houston Colt .45s’ Class A affiliate in the Sally League. Splitting his time as a starter and reliever, Crone won four of nine decisions, but knew it was time to quit. Just 29 years old, he ended his professional baseball career after the 1961 season. In an 11-season minor-league career, he won 90 games and lost 77 with a 3.42 ERA.

Upon retiring, Ray moved permanently to Hartford, Connecticut, where he had been living with his wife and four children in the offseasons since his trade from the Braves. For ten years he was out of baseball, but by 1971 he wanted to become involved again in his lifelong passion. “I didn’t feel I could coach,” Crone said. “They didn’t make much money and I didn’t think it was the thing to do with young kids.” He began scouting for the Montreal Expos in 1971, moved to the Baltimore Orioles a few years later, and then was named Southwest area scout by Orioles farm director Tom Giordano in 1977. Ray and his family moved to Texas, which he used as a base for his scouting excursions throughout the state and to Louisiana and New Mexico.

At a game in Beaumont game (Texas League) in the 1980s, he noticed a young, hard-throwing pitcher, Kevin Towers, who later became a scout after his playing career ended in 1989. When Towers was named the general manager of the San Diego Padres in 1995, he hired Crone as an area and subsequently local scout, a post he still held in 2012. “I take a lot of pride in being a scout and having been part of this game for so long,” said Crone.[13] At the major-league Winter Meetings in 2006, Crone was named the Midwest Scout of the Year. His son, Ray Jr., has served as scout for the Angels, Red Sox, and Tigers.

Involved in baseball for almost his entire life, Crone still resided in Waxahachie, Texas, as of 2013 and scouted Rangers’ home games for the Padres. “I went up through the system and paid my dues,” Crone said, reflecting on his life in baseball. “I played when baseball was at its height. I look back and know I could have done better. I didn’t do that and have to live with it.”

Last revised: July 1, 2014

This biography is included in the book “Thar’s Joy in Braveland! The 1957 Milwaukee Braves” (SABR, 2014), edited by Gregory H. Wolf. To download the free e-book or purchase the paperback edition, click here.

Notes

[1] The author expresses his sincere gratitude to Ray Crone, who was interviewed on June 19, 2012, for this biography. All quotations from him are from this interview unless otherwise noted.

[2] All minor- and major-league statistics have been verified on Baseball-Reference (baseball-reference.com).

[3] The Sporting News, September 16, 1953, 36.

[4] The Sporting News, November 3, 1954, 18.

[5] The Sporting News, June 8, 1955, 40.

[6] The Sporting News, June 15, 1955, 7.

[7] The Sporting News, January 4, 1956, 17.

[8] The Sporting News, February 22, 1956, 10.

[9] The Sporting News, May 23, 1956, 24.

[10] The Sporting News, October 24, 1956, 27.

[11] The Sporting News, September 4, 1957, 16.

[12] The Sporting News, January 14, 1959, 21.

[13] Lyle Spencer, “Crone Named Midwest Scout of the Year.” sandiego.padres.mlb.com, December 5, 2006.

Full Name

Raymond Hayes Crone

Born

August 7, 1931 at Memphis, TN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.