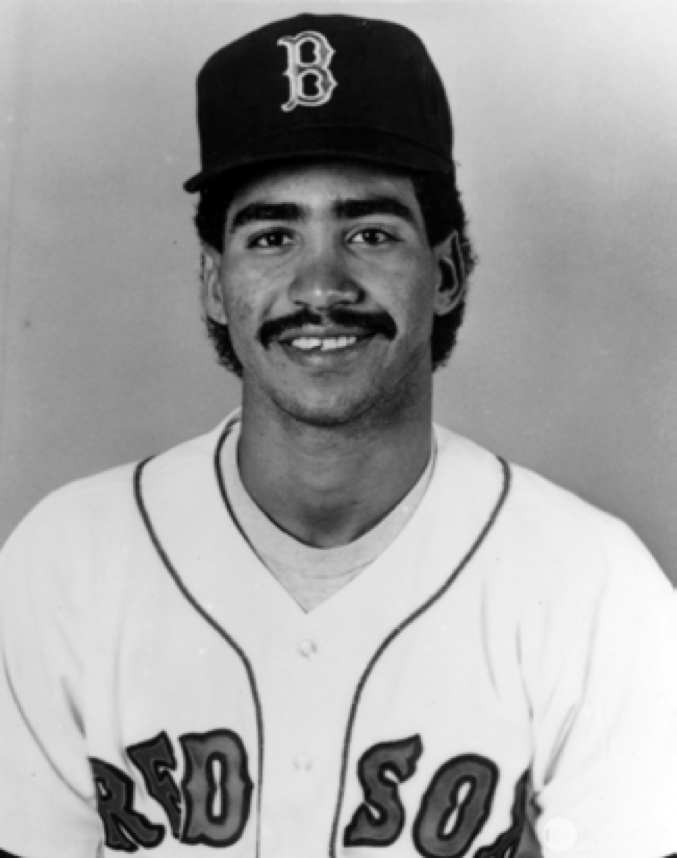

Rey Quiñones

Some baseball players have the luck of being in the right place at the right time. Many others never do. A few, however, momentarily have this kind of good fortune in their grasp, then see it taken away. Shortstop Rey Quiñones was a May call-up for the 1986 Boston Red Sox, a team destined to finish a single strike away from winning it all; but a celebrated midseason trade sent him away to last-place Seattle, and he missed out on being part of the postseason thrill (and ultimately the heartbreak) of being on this AL pennant winner.

Rey Francisco (Santiago) Quiñones, born on November 11, 1963, was raised in the Rio Piedras area of San Juan, which is home to the main campus of the University of Puerto Rico. Despite that distinction, Seattle Mariners scout Roger Jongewaard later called the neighborhood Rey lived in, “a very, very bad part of Puerto Rico.”1

He was signed by local Red Sox scout Felix Maldonado in 1982 as an amateur free agent, at a time when the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico was not yet subject to the annual amateur draft. A right-hander, he was of about average height for a professional shortstop, reaching an eventual 5-feet-11, and was of slender build, topping out at around 160 pounds. These are not vital statistics that suggest a power hitter; nonetheless, power turned out to be one of his tools.

Quiñones began his professional career at Elmira in the short-season New York-Penn League. Teammate Dana Kiecker later was quoted as saying of the 19-year-old Quiñones, along with two other Latin teammates on the Pioneers, that “[none of them spoke a word of English.”2 Command of the English language did not come up as an issue for Quiñones during the rest of his career, however. He acquitted himself very well in his first taste of minor-league ball, not only batting .295 but showing very good power with 11 doubles and 12 home runs in only 261 plate appearances. Not surprisingly for a young shortstop, he was error-prone and ended up with a .925 fielding percentage on 27 errors in 360 chances. He certainly was gaining the attention of others outside the Red Sox organization as well; Baseball America named him Boston’s number 2 prospect during the following offseason.3

Rewarded with a promotion to Winston-Salem in the full-season Carolina League in 1984, Quiñones continued showing good results. He batted .279, and again showed unusual power for a middle infielder, chipping in with 30 doubles, 6 triples, and 11 home runs. His fielding percentage while playing for the Spirits was marginally better than the year before, at .930.

Quiñones continued his climb toward the American League, with 1985 spent on the Double-A New Britain Red Sox squad in the Eastern League. Anointed by Baseball America as the top Red Sox prospect4 that previous offseason, he posted satisfactory numbers at the plate, batting .257 with 19 doubles, 5 triples and 9 homers against this tougher level of competition. His fielding percentage showed some further improvement, ending at .947.

Retaining his number-1 BA prospect ranking, Quiñones in 1986 had reached the brink of the majors, as he started in Pawtucket of the International League. During spring training, his swing had impressed Ted Williams, who dubbed him “a pup out of Frank Robinson.”5 (It is hard to guess exactly what Williams may have meant by the analogy, since physically it would be hard to match up the slightly built shortstop and the muscular outfielder. But Williams likely saw something reminiscent in the swing, and the youngster certainly sported home-run power, rare in a legitimate shortstop prospect.) Veteran Boston Globe sportswriter Peter Gammons perhaps heard this remark and phrased it this way: “The prize apparently is 18-year-old Puerto Rican shortstop Rey Quiñones, a 6-foot-1 Frank Robinson lookalike, who is leading the club in homers (4) and has exceptional defensive tools.”6 Sports cartoonist Eddie Germano recorded his spring-training thoughts that year, and in a cartoon titled “Winter Haven Sketchbook” he captioned under a rough drawing of a fielder taking a groundball: “Young Rey Quinonez sic … still learning, quick hands at short … good release.”7 Apparently this was not an uncommon rendering of the player’s name during his early career.8

In 24 games for the Triple-A PawSox, Quiñones batted .267 with two doubles and four homers in 98 plate appearances. His fielding percentage was up to .962, and the parent club deemed him ready. He was called up to Boston and was assigned uniform 51, a number he wore throughout his major-league career. He made his major-league debut on May 17, 1986, an 8-2 win over the Texas Rangers in which he got two hits and a walk in four plate appearances.

That victory was no isolated experience. Winning became a welcome habit during the first weeks Quiñones was in the majors. The Red Sox won 15 of the first 17 games after his promotion, May 17 to June 4. In that span he contributed greatly, with a .275 batting average in 65 plate appearances, with three doubles and a homer plus an impressive 12 walks.

But defense remained a bugaboo. No one doubted Quiñones’ talent and potential with the glove, but a .940 fielding percentage for his total time with the Red Sox attests to what were considered lapses in concentration. His hitting also came back to earth after that early success, with a batting average of .228, few walks, and only modest power. He was basically benched after being lifted for a pinch-hitter in the bottom of the eighth on August 5, in favor of Ed Romero, and played in only two more games for Boston. The team as a whole had also run into a bad slump (5-13) immediately after the All-Star break, coinciding partly with the July 10 suspension of pitcher Dennis “Oil Can” Boyd. Quiñones came in for a large share of the blame for the slide. Reviewing the 1986 season, Boston Globe journalist Dan Shaughnessy wrote, “[the Sox] were a mess. Baylor had only 2 homers in 6 weeks, Quiñones was erroring sic all over the place. …”9

Quiñones was traded to the Seattle Mariners on August 19, 1986. The Red Sox received shortstop Spike Owen and outfielder Dave Henderson in return for Quiñones, starting pitchers Mike Brown and Mike Trujillo, and outfielder John Christensen. However, it was actually a little more complicated than that. On Sunday, August 17, Red Sox general manager Lou Gorman had agreed to the trade with his Seattle counterpart Dick Balderson, and it was announced to the public.10 But, as Shaughnessy revealed, “[league officials had discovered a problem with the trade Monday afternoon. Gorman had failed to ask for waivers on Brown and Trujillo. Though only a technicality, the Sox GM had illegally traded two players and the deal was put on hold until it could be restructured.”11 The trade was finally closed on the 19th, with Quiñones going to Seattle immediately, Brown and Trujillo being sent on the 22nd after clearing waivers, and Christensen not going to the Mariners until late September as a player to be named later. The swap was generally well received by Boston fans. The trade was portrayed as giving up youth for experience in order to make a pennant push, although only Quiñones could be considered a young prospect among the players Boston gave up, while both of the Seattle players, even though established as major leaguers, were still in their mid-20s. Gorman later remembered, “It was a good ballclub when I took over. The nucleus was there, and I knew there were only a few things I needed to do to make the club a contender. … I decided that we could use another bat or two, with some pop, and a steadier shortstop.”12 This explanation left the implication that the team, going all-out for the pennant, wasn’t willing to ride out some growing pains at this critical infield position.

It turned out that there were underlying reasons for the trade. Quiñones had somehow become tainted by his association with Boyd.13 He had been renting a room in the Chelsea condominium owned and occupied by Boyd,14 and the relationship was apparently close enough that Boyd had lent Quiñones his Chevrolet Monte Carlo.15 When Boyd got into his July scuffle with police, both Quiñones and Boyd’s wife were nearby and were questioned about the incident by the police. No charges were filed against either of them, and charges were eventually dropped against Boyd too.16 But apparently Quiñones was in the wrong place at the wrong time, and it cost him in his professional life, or at least that is the interpretation offered by some.17

Moreover, the on-field staff and even the players had become less than enamored with the shortstop’s work habits, a view that was to follow him for the rest of his baseball career. Sportswriter Shaughnessy quoted manager John McNamara immediately after the trade was announced: “‘Spike Owen is the type of ballplayer that fits right into a ballclub. He fits into the chemistry of this ballclub. He and [Marty] Barrett are going to work well together. They complement each other,’ McNamara said. McNamara had started to say that Owen fit into the Sox system better than Quiñones, but stopped himself short.”18 Even if he didn’t say it, the implication was clear, and the core of the team seemed to agree with McNamara. Teammate Don Baylor was later quoted as saying, “You never know all there is to know about hitting. But Rey, he told Walter [Hriniak], the batting coach, ‘I’ll let you know when I need you.’”19 Shaughnessy also noted, “There was some fear in the Sox camp that Quiñones might develop into the next Dave Concepción, but [Baltimore manager] Earl Weaver shook his head and said, ‘In five years, he’ll be the same player he is now.’”20

In fairness, Quiñones’ teammates found him generally likeable. Shaughnessy found it worth remarking that when Quiñones was informed of the potential for a trade a day or so beforehand, he “was unfazed. He was joshing with his teammates as they readied for the flight to Minnesota.”21 Decades later, catcher Rich Gedman could recall no negative issues with him during the short time they played together.22

So Rey Quiñones’ short career with the Boston Red Sox was over, but he moved on to the Mariners with high expectations by his new team. “He could stand at home plate in the Kingdome and throw the ball into the second deck in center field,” [Seattle trainer] Rick Griffin said. “He had the best arm of an infielder that I’ve ever seen.”23 Sports Illustrated apparently revived the Ted Williams observation, by saying Quiñones ”has a classic hitting style and might be a Frank Robinson at shortstop.”24 His arrival in Seattle paid immediate dividends, not only for his new team but for the Red Sox as well, as he batted leadoff in Yankee Stadium and went 2-for-4, knocking in two runs plus making a sparkling defensive play, in Seattle’s victory over Boston’s chief rival, New York.

But just as with his multi-hit debut for Boston, this strong start did not signal lasting success at the plate or in the field. Indeed, Quiñones’ batting statistics for Seattle during the rest of 1986 were even worse than they had been for Boston. His batting average was only .189, with few walks and little power. And his glove work remained erratic, as he compiled a fielding percentage of only .945, which is not made better by looking at modern fielding statistics.25 In short, Quiñones was costing his team runs both with his bat and with his glove. Still, the Mariners stuck with him through the rest of their dreary 95-loss season, likely from an absence of better alternatives, and possibly also from an aversion to benching so quickly the centerpiece of their big trade.

Spring 1987 rolled around, and Quiñones again found himself at the center of controversy, this time entirely of his own making. Sportswriter Kirby Arnold chronicled some of the troubles in his book Tales from the Mariners Dugout: “He showed up late for spring training, telling the Mariners he had visa problems. ‘Uh, Rey,’ team president Chuck Armstrong told him, ‘you’re from Puerto Rico. You don’t need a visa.’”26 The Mariners press had reason to remember the day Quiñones finally arrived. “ ‘Rey was lying on his back, flat on the floor the whole time,’ [Larry] LaRue [of the News Tribune of Tacoma] said. ‘We conducted the interview that way, the three of us and [PR director] Dave Aust standing above him. Among other things, Quiñones told the writers that he didn’t need baseball, saying he owned a liquor store in Puerto Rico and could live off that.’”27 This attitude toward money would show up again with the player.

But when Opening Day 1987 arrived, Quiñones began to exhibit signs of becoming the hitter that observers had always been saying he could be. He started a little slowly, with just one hit in his first three games, but quickly brought his batting average above .300. Even though he tailed off a bit, his month of April was robust, with a .296 batting average and enough power to accumulate an OPS of .725, a highly acceptable rate of production from a starting shortstop, especially one who was still only 23 years old. His month of May was also good, with a slightly lower batting average compensated by four home runs and more walks. The team was also playing better, posting (barely) winning records in both April and May. Quiñones missed 11 games in early June due to an injury, but when he came back he went on an absolute tear for almost a month, batting .356 from June 17 to July 10, with three more home runs. On July 7, skipper Dick Williams trotted out the year-old scouting report yet again: “Ted Williams said, don’t mess with his stroke, and we haven’t.”28 Of course, in light of the remark made later by Don Baylor regarding an unwillingness to be coached, it is possible there was a veiled message behind the crusty manager’s comment.

Mariners trainer Rick Griffin was struck by Quiñones’ competitive spirit. As Kirby Arnold related it, “Griffin remembers two games, one in Detroit and one in New York, when Quiñones announced in the dugout, ‘This game is over, I’m going to hit a home run.’ Then he went to the plate and did it.”29 Griffin probably was referring to the May 5, 1987, game in Detroit, which was won 7-5 on the strength of a two-run blast by Quiñones in the top of the ninth off Willie Hernández. In his career Quiñones never hit a home run against the Yankees, so it is unclear what other game Griffin may have been thinking of. But the anecdote speaks to Quiñones’ presence as a teammate.

The remainder of Quiñones’ season at bat, mid-July through September, was more pedestrian, with only three home runs in 243 plate appearances, and a batting average of .257. Still, a seasonal batting average of .276 with an OPS of .715 seemed to mark his arrival as a major-league shortstop.

Consistency on defense continued to be the visible weak spot in Quiñones’ game. His league-average range was partially undone by the 25 errors he committed during the course of the season for a lackluster .959 fielding percentage.

Less visible, at least to the public at large, was the continuing dismay by the front office and manager at Quiñones’ approach to the game. There was an often-repeated story about the time in 1987 he angered his manager by making himself unavailable late in a game for pinch-hitting duty, because he was already in the clubhouse, busy reaching the seventh level of Super Mario Brothers on his Nintendo.30

Kirby Arnold documented an exchange as told by club president Chuck Armstrong before one game, among Quiñones, manager Williams, and general manager Dick Balderson. “’I’m a good shortstop, right?’ Quiñones said. ‘You’re a very good shortstop, Rey,’ Armstrong told him. ‘I could be the best shortstop in the American League,’ Quiñones said. ‘Yes you could,’ Armstrong replied. ‘I’m so good,’ Quiñones continued, ‘that I don’t need to play every day.’ Armstrong was stunned as Quiñones continued. ‘I don’t need to play every day, and you have other guys who should play so they can get better,’ Quiñones said. ‘So I don’t need to play tonight.’ Williams reworked the lineup, replacing Quiñones at shortstop with Domingo Ramos. … Other players on the team began calling Quiñones “Wally Pipp,” and he had only one question. ‘Who’s Wally Pipp?’ he asked.”31 Of course, Domingo Ramos was no Lou Gehrig, either.

The next year, 1988, Quiñones arguably had his finest season, even while his team sank back into 90-loss territory. He set a personal best in games played and increased his doubles production while matching his 1987 total of 12 home runs. Although his batting average declined to .248, the league as a whole had a lower offensive level. And his defense, while never airtight, was markedly more consistent, with fewer errors and good range, resulting in a slightly above average zone rating as a shortstop. By the numbers, Quiñones was a demonstrable plus for his team.

And yet the odd stories regarding the personal side of the player accumulated. He had been late to spring training again and had remained uncommunicative; “(T)here are telephones in Puerto Rico,”32 GM Balderson observed. He was “the subject of controversy when he left the Mariners without consulting the team to attend the funeral of a relative in Puerto Rico. He also demonstrated an unwillingness to play with a series of minor injuries that failed to reveal anything in X-ray examinations.”33 Tacoma sportswriter Larry LaRue wrote humorously in 1997, “Long before the Mariners had winning seasons, they had characters. Rey Quiñones once threatened to kill me until a teammate pointed out that the story that had so enraged him had been written by another writer for another newspaper. ‘They all look alike,’ Rey said.”34

Indeed, that 1988 spring holdout left lasting hard feelings with the front office. Notwithstanding his dryly humorous comment about telephones, Balderson did have a conversation with Quiñones before the latter came to camp, and it did not go well. “He alluded to his contract when I asked why he wasn’t here,” said Balderson, “and at one point he said he didn’t like my tone of voice. I told him I didn’t like the attitude, the tone this sets.”35 Quiñones did receive a pay raise, playing for either $120,000 or $150,000 that season, according to varying sources, up from the $85,000 he received in 1987 and the $60,000 he had been paid as a rookie.36 Balderson himself was replaced as general manager by Woody Woodward in July of that year, which may have earned Quiñones somewhat of a clean slate with the front office, coupled with the fact that Dick Williams had been succeeded as manager in June by Jim Snyder. Snyder in turn was replaced by Jim Lefebvre during the offseason.

But if Quiñones had been handed a chance for a fresh start in 1989 with the new management crew, he seemingly took little advantage of it. He again delayed his arrival at spring camp, despite the prospect of receiving another pay raise. The local press seemed to take the side of management, with, for example, one writer leading a day’s story, “The Seattle Mariners are missing a key player, but it’s (hardly) been noticeable,”37 after a spring win brought the team to a 5-0 record. The article went on to provide some background: “The Mariners announced they have sent top scout Roger Jongewaard and instructor Marty Martínez to Puerto Rico to search for Quiñones, who was unhappy with his contract last season. The club said it hoped Jongewaard and Martínez would return with Quiñones to their Tempe, Arizona, training camp by the end of the week. Meanwhile, General Manager Woody Woodward renewed Quiñones’ contract. Though terms weren’t announced, Quiñones probably won’t be happy with them. He made $150,000 last season, wanted $300,000 this year, and now faces the prospect of coming to camp to pay a healthy fine — $1,000 a day since March 1 — and a base salary the same as in 1988.”38 Sources later stated that Quiñones earned $215,000 that year, but the fines for arriving late may have eaten into that figure.39

The story of tracking Quiñones down became even stranger as further details came out. He was literally hiding, in a house across the street from his home, when Jongewaard reached his neighborhood, but Quiñones’ girlfriend helped get the parties together. Jongewaard later related, “We finally got to talk to Rey for a just a couple of minutes. I told him that if he reported to camp and played this one year, he could very well earn himself a million-dollar contract the next year. Rey said he didn’t need the money because he had $30,000 in the bank. A week or so later, he finally showed up at spring training.”40

If Quiñones thought he could redeem his season with good play after a rough spring, the way he had done the previous two years, he was mistaken this time. He missed the first eight games of the regular season, then played in only seven, batting a measly .105 and making three errors at short. Rookie manager Lefebvre had already seen enough. GM Woodward later remembered, “He told me, ‘Woody, you gotta get this guy out of here, he’s driving me crazy.’ I told him I had one shot and I’d give it a try.”41 The Mariners abruptly traded him to the Pittsburgh Pirates along with pitcher Bill Wilkinson, for outfielder Mark Merchant (a first-round draft pick in 1987), starting pitcher Mike Dunne, and starting pitching prospect Mike Walker. (As an irrelevant side note, this brought to four the number of players named Mike included in trades involving Rey Quiñones.)

The Pirates clearly were hoping to succeed with a reclamation project, but it didn’t go that way. Quiñones remained in the same batting funk as with the Mariners that season, hitting just .209, and with only a little power and a few walks. His defense was judged to be subpar as well. After 71 games in a Pirates uniform, at age 25, Quiñones was released outright on July 22, 1989.

Quiñones never played in the major leagues again. There was a report that after the 1989 season he “was playing well in winter ball, had a number of teams interested in him and then started being late for games. Finally, he stopped showing up altogether.”42 Very likely he has played afterward, here and there, in leagues where official records do not reach the major media sources. Unexpectedly, after a long hiatus from the US spotlight, he showed up in 1999 in the independent Atlantic League, playing shortstop for the Atlantic City Surf, with a low batting average, a few extra-base hits, and unimpressive fielding statistics.

In 2012 the name Rey Quiñones showed up again in the news, once more in a way that was just a little off-kilter. According to Sports Collectors Digest, “An aggressive bidder from New York stepped up to the plate and slammed one out of the park by purchasing an actual 1996 New York Yankees World Series ring once owned by former ballplayer Rey Quiñones for $15,600. The sale took place during the 20th annual Cabin Fever Auction held March 25, 2012, by Tim’s, Inc. Quiñones was a shortstop who played for three teams from 1986-1989 (the Boston Red Sox, Seattle Mariners and Pittsburgh Pirates). He held an administrative position with the Yankees in the 1996 season, entitling him to a ring. It was a beauty, featuring 1.5 ounces of gold, 23 brilliant round cut diamonds (one for each Yankee championship team) plus a faux sapphire.”43

When contacted in 2015, the Yankees media relations office was unable to confirm either that Quiñones had ever worked for the team, or that he had received a World Series ring from them.44

What Quiñones has been doing to earn a living in recent years might not bear close scrutiny. A former ballplayer from Puerto Rico confided in December 2015 that Quiñones was operating in a “dangerous area,” and said further, “Hopefully, one day we don’t see him in jail.”45

In the career of Rey Quiñones there is an element of classic tragic drama — where the factors of both success and failure are contained within the nature of one character and cannot be separated. The ingredients for a successful baseball career were apparent to many knowledgeable people in the game during his rise. But the comments of other knowledgeable people after the fact are tinged with great regret. Mariners trainer Rick Griffin, who was mentioned earlier from Kirby Arnold’s book as attesting to the strength of Quiñones’ arm, said further of the player, “[to this day, I think he is one of the most talented guys I’ve ever seen. But he didn’t really care about playing the game. He enjoyed being there, but he didn’t want to play.”46 He also remarked, “[it’s a sad deal. You always wondered what kind of a player he could have been, but he just didn’t have his priorities in order.”47

“‘Oh, Quinones,’ [Seattle GM Balderson said in 1991. ‘He broke my heart. He had the potential to be the best in the game, but what a strange guy.’”48

Jim Leyland, Quiñones’ last major-league manager, was even more pointed in a 1989 interview with New York Times writer Murray Chass, and his up-close view, as summarized by Chass, deserves to be quoted at length. ”I thought we were getting someone who wasn’t the best of guys but had talent,” the Pittsburgh manager said. “[Instead, we got a guy who was a good guy but didn’t show talent. I can put up with errors, but not errors with no effort. It was performance No. 1, approach to performance No. 2. He wasn’t getting balls and he wasn’t making an effort to get balls. He has a good arm, but he was lollipopping the ball over to first. I tried everything with him; I encouraged him. One day I said something to him about throwing the ball and that night he went out and flipped it underhand to first. He and his wife have a baby, and my wife is going to have a baby for the first time, and we’d kid about that. Then the game would start and he’d nonchalant the ball. I don’t know why. I’d like to be inside his mind three games in a row to understand the way he thinks. He was not a problem off the field, only on the field. He’s a personable guy, a good kid. He jokes around. He never caused any problems. From what we had heard, we thought maybe he’d get to the park late. But we never saw any of that. He was always on time. We traded three guys for him. That should’ve told him something. We rolled out the red carpet for him. He had a reputation with Boston and Seattle of being a lackadaisical player. I went to bat for him. I defended him. But he kept playing lackadaisically. We evidently made a mistake getting him. He had problems in Boston, Seattle and here. That was why we decided not even to make the attempt to send him down. We just wanted to cut the cord.”49

Mariners teammate and fellow Puerto Rican Henry Cotto expressed his view more simply. “Rey Quiñones is hard to understand.”50

Sources

In preparing this biography the author relied greatly on the biographical and career information provided online at baseball-reference.com and is very grateful for the existence of this resource. Additional sources are referenced in the text and the Notes.

Notes

1 Bart Wright, Remember Rey Quiñones? Those Were the Days (web.kitsapsun.com/archive/1998/03-31/0002_bart_wright__remember_rey_quinone.html, 1998).

2 David Laurila, Interviews From Red Sox Nation (Hanover, Massachusetts: Maple Street Press, 2006), 98.

3 Baseball America, “1983-2000 Top 10 Prospect Rankings Archives.” baseballamerica.com/majors/top-10-prospect-rankings-archives/.

4 Ibid.

5 Dan Shaughnessy, One Strike Away (New York: Beaufort Books, 1987), 141.

6 Chad Finn, Top 50 Red Sox Prospects of Past 50 Years, (boston.com/sports/touching_all_the_bases/2014/04/20-11.html, 2014).

7 Eddie Germano, Red Sox drawing board: 25 years of cartoons (Lexington, Massachusetts: The Stephen Greene Press, 1989), 119.

8 Finn; Baseball America, “1983-2000 Top 10 Prospect Rankings Archives.”

9 Shaughnessy, 117.

10 Glenn Stout and Richard A. Johnson, Red Sox Century — the Definitive History of Baseball’s Most Storied Franchise (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2000), 400.

11 Shaughnessy, 117.

12 Laurila, 242.

13 Stout and Johnson, 400.

14 Michael Madden, Boston Globe, July 12, 1986.

15 Shaughnessy, 108.

16 Kevin Cullen, Boston Globe, July 17, 1986.

17 Finn.

18 Shaughnessy, 141.

19 Ibid.

20 Shaughnessy, 142.

21 Shaughnessy, 137.

22 Rich Gedman, personal interview with author, November 28, 2015.

23 Kirby Arnold, Tales From the Mariners Dugout (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing, 2007), Chapter Eight.

24 Sports Illustrated, September 1, 1986.

25 fangraphs.com/statss.aspx?playerid=1010615&position=SS#fielding.

26 Arnold, 63.

27 Ibid.

28 Associated Press “With Ted’s Advice, Quinones May Gain Clout of ‘Sugar Rey,’ ” Spokane Chronicle, July 7, 1987.

29 Arnold, 62.

30 Art Thiel, Out of Left Field (Seattle: Sasquatch Books, 2003), 21.

31 Arnold, 63-64.

32 Larry Larue, “Quiñones Missing From Seattle Camp,” Tacoma News-Tribune, February 29, 1988.

33 Mike Shatzkin, ed., The Ballplayers (New York: William Morrow and Company, 1990), 888.

34 Tacoma News-Tribune, July 8, 1997.

35 Larue, Tacoma News-Tribune, February 29, 1988.

36 baseball-reference.com/players/q/quinore01.shtml.

37 Associated Press, “Marines Don’t Miss Holdout Quinones, March 8, 1989.

38 Ibid.

39 baseball-reference.com/players/q/quinore01.shtml.

40 Wright, Remember Rey Quiñones? Those were the days.

41 Ibid.

42 Bob Finnigan, “Reynolds Looks Like a Million; Presley Looks Like a Red Sock,” Seattle Times, January 14, 1990.

43 Tom Bartsch, “1996 N.Y. Yankees Ring Tips Scales at $15,600,” Sports Collectors Digest, May 29, 2012.

44 Yankees Media Relations office, telephone interview with author, December 1, 2015.

45 Bill Nowlin interview with former Puerto Rican ballplayer. December 20, 2015.

46 Arnold, 61.

47 Arnold, 63.

48 Bob Finnigan, “Argyros’ Discards Shine Elsewhere,” Seattle Times, July 9, 1991.

49 Murray Chass, “Release of Quiñones Explained by Leyland,” New York Times, July 27, 1989.

50 pitchersandpoets.com/2012/04/24/rey-quinones-a-hard-man-to-understand/.

Full Name

Rey Francisco Quinones Santiago

Born

November 11, 1963 at Rio Piedras, (P.R.)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.