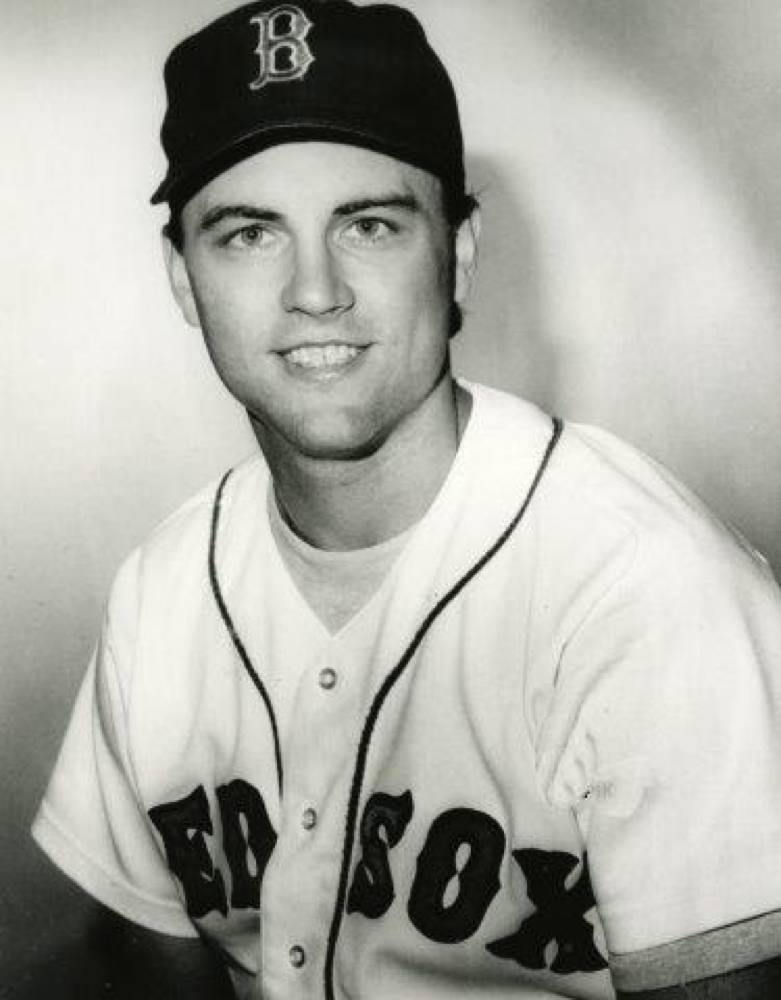

Spike Owen

The list of major-league record-holders contains names familiar to all baseball fans — Hank Aaron, Babe Ruth, Nolan Ryan, Spike Owen … wait a minute! Spike Owen?

Yep. While his name won’t roll as easily off the casual fan’s tongue as some others would, Spike Owen was indeed a record-setter during a steady 13-year career, primarily as a switch-hitting shortstop, with the Mariners, Red Sox, Expos, Yankees, and Angels.

Spike Dee Owens was born in Cleburne, Texas, on April 19, 1961 to Don Owen, who owned a used car dealership, and Margie (nee Spikes, and yes, that’s how he got his name) Owen, a homemaker. He and his older brother, Dave, who had a brief career with the Cubs and Royals, were always playing sports with the strong support of his mom and dad.

“I don’t recall (his parents) ever missing a Little League game we played in,” Owen recalled. “And Dad was always out in the backyard throwing balls to me and Dave, whatever season it was.”1

Owen developed his skills first at Cleburne High School, where he was voted to the Class 3A All-State tournament team at shortstop in 1979. After graduating, he began a decorated career with the University of Texas, where he played for a powerhouse team that went to the College World Series in 1981 and 1982.2 Although the Longhorns didn’t win the championship in either season, Owen distinguished himself in the field and at the plate. He had 10 assists in a 1981 CWS game and tied a career record, which still stood as of 2015, for most triples, with three. He also led the 1982 tournament with a .529 batting average. Owen’s accomplishments were honored in 2010 when he was named shortstop on the NCAA CWS Legends Team chosen to commemorate the closing of Johnny Rosenblatt Stadium, home of the College World Series since 1950.

Owen’s junior year at Texas in 1982 was one for the ages. He hit .336 with a .478 on-base percentage and 39 stolen bases. The honors rolled in that year; he was a first team All-American (after being a third team All-American in 1981), was voted to the All Southwest Conference All-Star Team by the Associated Press, and was named the Longhorns’ team captain.

That combination of skill and leadership made Owen an attractive commodity to major-league teams. After finishing his junior year, Owen decided to make himself available for the 1982 amateur draft. The Seattle Mariners chose him in the first round and sent him to the Lynn Sailors of the Double-A Eastern League, where he batted .266 with one home run and 27 RBIs in 78 games. The Mariners were impressed enough with Owen’s performance at Lynn to promote him to Triple A with the Pacific Coast League’s Salt Lake City Gulls for 1983.

Even before he reported to the Gulls, Owen took a big step forward in his life when he married Gail Lockhart on New Year’s Day 1983. The couple have four children.

Owen was showing similar numbers in Salt Lake City (.266, one home run, 32 RBIs in 72 games) when he became the beneficiary of a major shakeup by the parent team. After winning no more than 67 games in any season during their first five years of existence, the Mariners showed some promise in 1982 when they finished with a 76-86 record, good enough for fourth place in the American League West Division. The 1983 edition wasn’t living up to expectations and on June 25 manager Rene Lachemann was fired and replaced by Del Crandall. The Mariners also designated incumbent shortstop Todd Cruz (as well as pitcher Gaylord Perry) for assignment and brought Owen up to replace Cruz. He got a hit in his first at-bat as the Mariners ended an eight-game losing skid with a 5-2 victory over the Toronto Blue Jays. Owens was thrilled to finally arrive in the majors, but it is fair to say that the circumstances and his timing on arriving in a big-league locker room could have been better because he showed up just after the team found out about the changes.

“I was in the room for five minutes and was so happy at being here,” he said. “I didn’t realize I was the only one acting happy.”3

That awkward moment aside, player development director Hal Keller, the man who picked him in the draft, saw qualities in Owen’s play that he felt could help the Mariners. “I don’t expect him to hit .350,” Keller said, “but he’s doing everything the way we expected. We looked at his lifestyle, his enthusiasm, and his hard-nosed approach to the game and we liked what we saw.”4

As it seldom does, changing managers didn’t improve the team, and Seattle went on to a 60-102 record. But Owen made the shortstop position his own, despite hitting only .196 in 80 games. The Mariners were a young team, with 11 players 25 or younger on their 25-man roster, and growing pains were to be expected.

The Mariners began the 1984 season with a scorched-opponent policy, winning six of their first seven games, including a walk-off 3-2 victory over Toronto in the home opener in which Owen scored the deciding run. They even swept the eventual World Series champion Detroit Tigers in a three-game Memorial Day weekend series in Seattle. Owen’s season also started well; he had an 11-game hitting streak between May 5 and 16 that pushed his batting average up to .309.

“It’s just one of those things,” Owen said at the time. “I worked hard on my swing during the offseason, and I’m really feeling good up there now.”5

As well as Owens was playing — Keller, who became the general manager in 1984, put the brakes on a deal that would have brought U.L. Washington over from Kansas City — both he and the team cooled off. By August 31 the Mariners had a 59-76 record and Crandall got the boot because he wasn’t getting the most from his players. Chuck Cottier was named interim manager despite never having managed above Class A, and his relaxed managing style propelled the Mariners to a 15-12 record the rest of the way. It’s hard to tell whether Crandall’s more authoritarian style affected Owen’s play. His batting average fell to .245 for the year, but he did have career highs with 16 stolen bases, 130 hits, and 67 runs scored. He also finished third among American League shortstops with a .977 fielding percentage.

As the 1985 season approached, it was clear that the Mariners were counting on young, home-grown players like Owen, because they didn’t make any significant moves in the offseason. “We think one of the problems the Mariners have had in the past is not having continuity,” said club president Chuck Armstrong. “We have striven hard to maintain continuity and not trade away our stars. I’d rather go with Alvin Davis, Mark Langston, Jim Beattie, Spike Owen — what I think are going to be big names for us — as opposed to guys on the decline, which is what this franchise has done time and time again.”6

In “the best laid plans …” department, the 1985 season was full of highs and lows for Owen and the Mariners. Again the team was hot out of the gate, winning its first six. But 12 losses in the next 13 games killed any momentum the Mariners might have had, and they ended up duplicating their 74-88 record. For his part, Owen started off poorly at the plate; on May 29 he was hitting .193. He went through some highs and lows after that. He enjoyed the high of being named American League Player of the Week for the week of June 23-30, when he hit .500 with two triples and two home runs. He then missed the last two weeks of July with a pulled hamstring, an injury that recurred throughout his career. He was back for one game on August 2, then didn’t play until August 10, missing 19 games in that stretch. Owen managed to haul his average over the Mendoza Line for the season to a respectable .259, with 6 home runs and 37 RBIs. His .975 fielding percentage was third in the league.

Owen’s 1986 season could have been made into an Andrew Lloyd Webber musical because it began with disappointment, rose to a euphoric crescendo, then came crashing down like a chandelier in an opera house. Prior to the season, The Sporting News said that the 1986 edition of the Mariners was the best in team history — on paper. Maybe if the team’s grounds crew replaced the Astroturf in the Kingdome with papyrus, the Mariners would have had a better season; instead they were a disaster from the get-go. They didn’t even bother teasing their fans with a hot start, going 7-14 in April and continuing downhill from there. Talented young players like Owen, Harold Reynolds, Alvin Davis (1984 Rookie of the Year), and Mark Langston (1984 Rookie of the Year runner-up) were not jelling as a team, even after the nomadic Dick Williams became manager on May 9.

Owen did his part as a team leader right from spring training, welcoming new teammate Steve Yeager by giving him his number 7, which Yeager wore with the Dodgers. He was also at his shortstop position on Opening Day despite having missed 10 Cactus League games due to his chronic hamstring problem. But just as the rest of the team wasn’t performing, Owen’s main strength, his defense, was also falling off. After committing 14 errors in all of 1985, he made his 15th miscue of 1986 on July 4, and ended up with a career-high 21 for the season. Owen typified how the Mariners’ season went when he became the answer to a baseball trivia question on April 29. On that night former Texas teammate Roger Clemens, now pitching for Boston, struck out 20 Mariners to set a new single-game record, breaking the old mark of 19 shared by several pitchers. Owen was the record-tying whiff in the top of the ninth.

As optimism turned into the calamity that ended up as a 67-95 season, Mariners management opted to unload some players. On August 19, Owen and Dave Henderson were traded to the Red Sox for rookie shortstop Rey Quiñones and three players to be named later.7 After that year’s World Series, this is how Phil Elderkin of the Christian Science Monitor assessed the acquisition of Owen:

“What Boston saw in Owen was a steadying influence at shortstop, a guy with soft hands who could consistently make the routine plays every team needs to become a contender. Even if his throwing arm wasn’t registered with the National Rifle Association, it was plenty good enough.”8

For his part, Dick Williams thought that Owen’s leg problems had diminished his ability. “I’m not taking anything away from Spike, Spike’s legs are gone,” he said in spring training 1987. “He’s very, very shaky as a shortstop. He’s a great competitor, but his legs were going on him before I joined the ballclub.”9

Owens’ legs were just fine, thank you, in his third game with Boston. In a 24-5 pasting of the Cleveland Indians on August 21, he went 4-for-5 with a home run and a major-league record-tying six runs scored. His tootsies were a little tender after it was over. “My feet are a little sore,” he said. “I did a whole lot of running, but it was well worth it.”10

The Red Sox won the American League pennant by 5½ games over the Yankees in a tough division in which five of the seven teams finished above .500. Owen’s hitting stats for the regular season were typical (.231 batting average, one home run, 45 RBIs), but he batted .429 in the American League Championship Series against the California Angels and scored five runs in seven games — although his defensive prowess disappeared as he committed five errors — to help propel the Red Sox to their first World Series since 1975.

Owen’s first — and only — taste of World Series play was like the Bizarro world of the old Superman comics, where everything happened in reverse. The normally light-hitting shortstop batted .300 in the fall classic. As well, he, along with his teammates and all of Red Sox Nation, had to endure a crushing Series loss to the New York Mets; Boston was one out away from winning it all in the infamous (from the Red Sox’ point of view) Game Six, before blowing a two-run lead in the 10th inning. Owen went 3-for-4 in that game with a run scored. The Mets won Game Seven to become world champions.

A tough postseason series loss can affect a team the next season, and such was the case with the 1987 Red Sox. They never really got on track and finished 78-84 for the year. After winning the starting job in spring training, Owen started horrendously, getting only five hits in his first 35 at-bats, and was benched for more than a month. He came back on May 24 and hit more consistently upon his return, finishing with a .259 batting average — despite an 0-for-29 slump in late August — with 2 homers and a career high 48 RBIs. He got more than half of those RBIs in a total of 11 games; he had six games with three RBIs and another five games in which he drove in two.

Owen must have felt like the old gunslinger from the Wild West forced to contend with a young hotshot when he arrived at spring training in 1988. Jody Reed, who hit .296 at Triple-A Pawtucket, was the latest threat to his job. If this had been a movie gunfight, it would have looked more like Laurel against Hardy than John Wayne against Gary Cooper. Manager John McNamara penciled Owen in the Opening Day lineup, then benched him after he started 3-for-27, in favor of Reed. Reed went 1-for-17, so Owen went back in.

“Both played excellent defensive shortstop, and I’m waiting for one to get hot at the plate,” said McNamara.11

The plate was actually cold for the entire team early in the season, as the Red Sox faced such a total lack of home-run power that their total of nine home runs after 24 games was one more than the number hit by Oakland’s José Canseco. Owen was tied for the team lead in home runs, with two, which was amazing for a roster that included Jim Rice, Dwight Evans, and Wade Boggs. It was only a matter of time before the front office made some changes.

Those changes began during the All-Star break, when McNamara was fired and replaced by baseball lifer Joe Morgan. The Red Sox went on a tear, winning 19 of their next 20 games, and Owen watched 16 of those games from the bench. He was also the cause of a dugout shoving match between Morgan and team captain Rice, after Morgan sent Owen in to pinch-hit for Rice during a July 20 game, which, let’s face it, was like replacing Michelangelo with a house painter. Rice was suspended for three games, Morgan’s authority was asserted, and Owen’s fate with the Red Sox was sealed. Owen played sporadically as Captain Morgan led the Red Sox to the American League East title. Oakland swept the Red Sox in four straight in the ALCS — there must have been something in the juice — with Owen having only one plate appearance, in the top of the ninth in Game Four, as the Red Sox desperately and unsuccessfully tried to extend the series. That was Owen’s last game in a Red Sox uniform. He had wanted to be traded after Reed got the starting job, and got his wish on December 8, 1988, when he was sent to the Montreal Expos along with minor leaguer Dan Gakeler for pitcher John Dopson and infielder Luis Rivera.

In his prognostications for the 1989 National League season, Peter Pascarelli of The Sporting News predicted that the Mets would win 100 games, the San Francisco Giants would finish fifth in the NL West and the Expos would do likewise in the NL East, citing Owen as “an average filler for the Expos’ gap at shortstop…”12 Pascarelli was wrong on all counts; the Mets finished second to the Cubs, the Giants went to the World Series and Owen provided solid fielding and leadership as the Expos finished fourth with an 81-81 record. He led the National League in fielding percentage (.979) and committed 13 errors in 633 chances. His offensive numbers were typical for him, a .233 average, 6 home runs, and 41 RBIs. The Expos were pleased enough with Owen’s performance to give him a three-year contract extension during the season.

For a player relied on more for his defense than his offensive contribution, Owen’s 1990 season couldn’t have gotten off to a better start, as he set a National League record for consecutive errorless games with 63, breaking the previous mark of 60 set by the Mets’ Kevin Elster in 1988. Game 61 was a piece of cake — he didn’t have any groundballs hit to him, no putouts, and only one assist in a 2-1 loss to the Cubs on June 19. That record propelled him to a career-high .989 fielding percentage (again tops in the league) and a career-best six errors. Owen’s defense contributed to a competitive 85-77 season for Montreal; the team was 4½ games out on September 20, but a 1-9 stretch knocked them out of the race.

The 1991 season collapsed on the Expos — literally. A 55-ton slab of Olympic Stadium concrete fell in early September, forcing the team to play its last 13 home games on the road. And while no one was hurt as a result, the event only added insult to the injury of a 71-90 season. Owen’s numbers were typical — .255 batting average, 3 home runs, and 26 RBIs, along with a .986 fielding percentage (second in the league) — but the media were already talking about Owen being on the way out. Montreal had a rising star shortstop named Wilfredo Cordero playing at Triple A and projected to take the starting job at shortstop in 1992.

To borrow an old cliché, if Owen had a nickel every time someone was taking his job, blah, blah, blah, and 1992 was no different. Once the season started, Owen was at shortstop and Cordero was back in the minors. There was a bit of a difference this time, as Owen was 31, and again had problems with his hamstring; he was on the 15-day disabled list in July. He was also in the $1 million salary range, which was a lot for a cash-strapped team like the Expos at the time. Even though he had a career high seven home runs and the highest batting average of his career to date at .269, the Expos wanted to get younger and cheaper.

Owen became a free agent after the season, and signed a three-year, $7 million contract with the Yankees. He loved playing in New York, and he knew that playing in the 1993 home opener wearing pinstripes was a special memory. “The atmosphere in parks like Yankee Stadium is so unique and hard to beat with the history and all the great players and all the ghosts,” he said. To see the stadium jam-packed for a beautiful day game, even when I talk about it now it still gives me goosebumps to think I was out there and part of that game.”13

The feeling, however, was not mutual. Owen started off very well, hitting .419 in his first 12 games. The adrenaline rush of playing in Yankee Stadium soon went away, as did Owen’s starting job. He was benched in favor of Mike Gallego after the All-Star Game, and had only nine starts in the last two months of the season. He played in 103 games and had only two home runs and 20 RBIs along with 14 errors. After the season, New York traded him to the California Angels, and assumed a substantial part of the remaining $4.25 million of his contract.14

Owen spent the final two years of his major-league career as a part-time player with the Angels. He played 82 games in each of the 1994 and 1995 seasons. For the two seasons combined, he batted .274 with 4 home runs and 65 RBIs. He called it a career in April 1996, 2½ weeks after signing a minor-league contract with the Texas Rangers.

After his playing career ended, Owen went back to his alma mater at age 37 to obtain his degree in applied learning and development with an emphasis on sports management. In 2002 he started the first of two stints as a coach with the Round Rock Express, the Houston Astros’ affiliate in the Double-A Texas League, and had two stints with them. The first lasted until 2006; he then returned from 2011-2014. As of 2015, he was manager of the High Desert Mavericks, the Rangers’ affiliate in the Class-A California League.

Sources

In addition to the sources listed in the Notes, the author also used the following:

Thebaseballcube.com.

Baseballpilgrimages.com.

Galveston (Texas) Daily News.

Index Journal (Greenwood, South Carolina).

Ludington (Michigan) Daily News.

Mocavo.ca.

New York Times.

Omaha.net.

Oursportscentral.com.

Orlando Sentinel.

Paris (Texas) News.

San Bernardino County (California) Sun.

NCAA.org.

Special thanks to Shane Phillips of the High Desert Mavericks for his assistance.

Notes

1 Kurt Kragthorpe, “Owen-Reynolds Combination Clicks,” Deseret News (Salt Lake City, Utah), June 15, 1983.

2 The 1981 team included pitcher Calvin Schiraldi while the 1982 team included Schiraldi and Roger Clemens. Both later played with Owen on the Red Sox.

3 “Mariners’ Owen adds lift to troubled team,” Evening Journal (Lubbock, Texas), July 5, 1983.

4 Ibid.

5 Bill Plaschke, “Thomas Accepts Shoulder Surgery,” The Sporting News, May 28, 1984: 20.

6 “Mariners Stood Pat During Off-Season,” Los Angeles Times, February 24, 1985.

7 The players to be named were Mike Brown, Mike Trujillo, and John Christensen.

8 Phil Elderkin, “Seattle-to-Boston trade definitely agreed with two Sox stars,” Christian Science Monitor, October 28, 1986.

9 Dan Weaver, “Mariners’ manager has mellowed … just a little bit,” Spokane Chronicle, January 29, 1987.

10 “Swindell’s debut includes 24-5 shellacking,” Baytown (Texas) Sun, August 22, 1986.

11 “A.L. East,” The Sporting News, May 2, 1988: 21.

12 Peter Pascarelli, “Best Bets: Phils and Braves as Cellar Dwellars,” The Sporting News, March 6, 1989: 14.

13 Ed Randall, More Tales From the Yankee Dugout (New York: Sports Publishing LLC, 2002), 84.

14 The New York Times on December 10, 1993, said it was unlikely the Angels would have agreed to the trade if the Yankees did not assume at least $2 million of Owen’s salary.

Full Name

Spike Dee Owen

Born

April 19, 1961 at Cleburne, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.