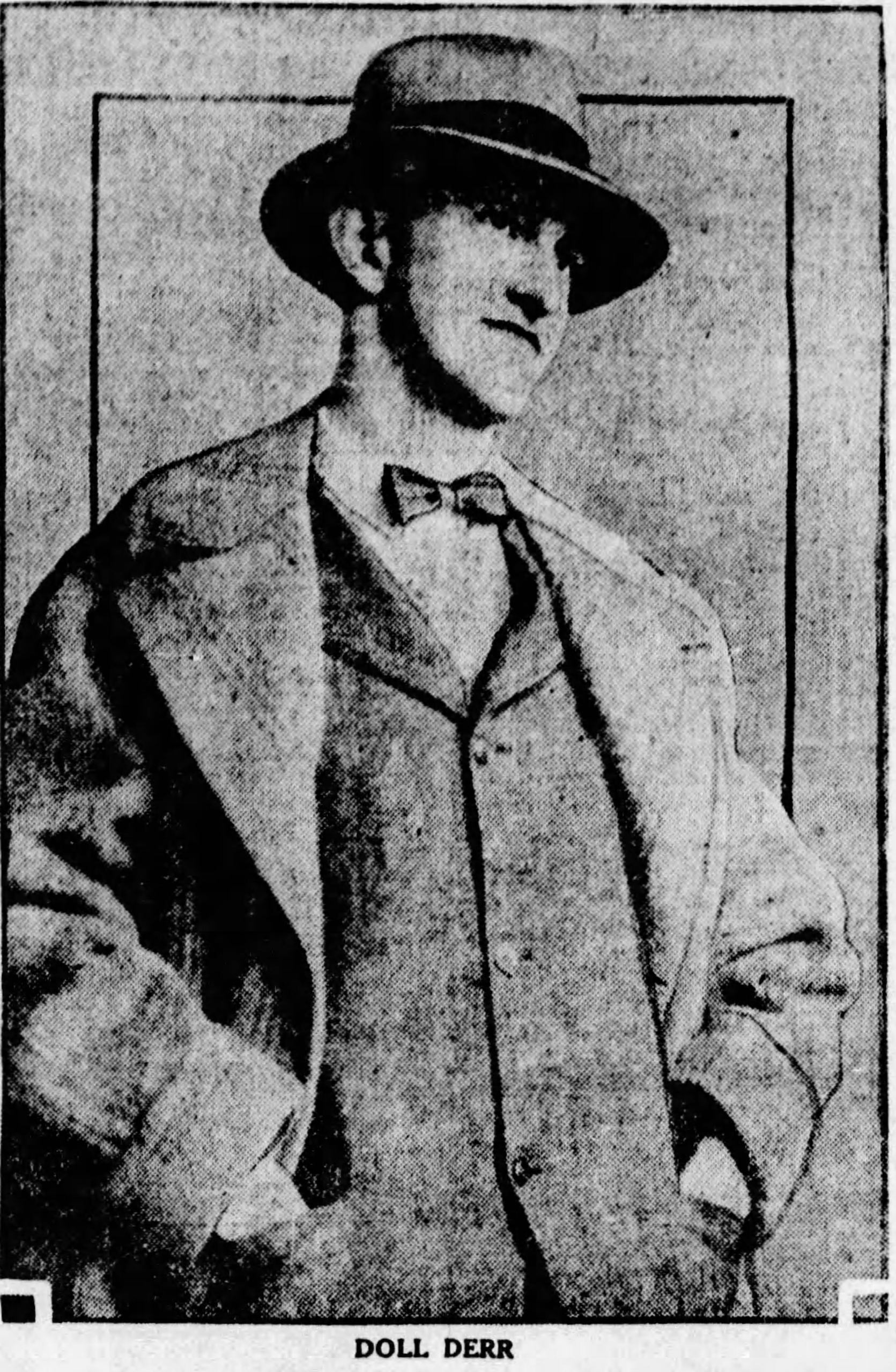

Doll Derr

From calling baserunners safe to keeping schoolchildren safe, Luther Derr Sahm had a long and eventful life – much of it spent under a professional alias. He called himself Doll Derr,1 and it is under that distinctive name that he appears in major-league records as an umpire in the National League for 28 games in April and May of 1923. The story of his umpiring career is the one of a tough, long-gone era when dodging fists and thrown bottles was as much part of an arbiter’s lot as calling balls and strikes.

From calling baserunners safe to keeping schoolchildren safe, Luther Derr Sahm had a long and eventful life – much of it spent under a professional alias. He called himself Doll Derr,1 and it is under that distinctive name that he appears in major-league records as an umpire in the National League for 28 games in April and May of 1923. The story of his umpiring career is the one of a tough, long-gone era when dodging fists and thrown bottles was as much part of an arbiter’s lot as calling balls and strikes.

Luther Derr Sahm was born on November 22, 1891, in Frederick, Maryland, about 50 miles west of Baltimore. He was the son of Harry J. Sahm and Etta G. (Derr) Sahm, who had been married in Baltimore about two years earlier.2 According to local newspapers, Harry Sahm was an engraver, also noted for pen art. At one point, he worked for a local printing company called Marken & Bielfeld, which remained in operation well into the 20th century.3

Young Luther Sahm’s maternal grandfather, Luther C. Derr, was a well-known name in Frederick. He served at various times as sheriff; chief of police; superintendent of Montevue Hospital, an asylum for the mentally ill and indigent; and assistant superintendent of the local prison. He was active in local Democratic politics and an “ardent admirer of sports” with a special fondness for baseball.4

Luther C. Derr had particular opportunity to influence his grandson and namesake. In the summer of 1894, Etta Sahm was granted a divorce from her husband and given custody of “the child,” not yet three years old.5 The 1900 and 1910 U.S. Censuses show Etta and her son living with Luther C. Derr, his wife, and Luther’s other children in Frederick.6

The first available published reference to “Doll Derr” occurred not long after the 1910 Census. On November 25, 1910, the Baltimore Sun and Evening Sun took note of a football player on the Frederick YMCA team named Doll Derr who suffered a serious chest injury in a game against the Maryland Athletic Club of Baltimore. With three doctors on hand to treat him, the evening paper reported his condition as “improved.”7

The young man continued to show up in Frederick-area news reports for several years in a variety of sporting roles – playing basketball; making “two pretty catches” for a YMCA baseball team; unexpectedly tying for first place in a high-jump competition; and, as a predictor of his future career, refereeing a college basketball game.8 Doll Derr, clearly, was capable of athletic success in whatever he tried.

As best as can be determined, Sahm never publicly explained the origin or meaning of the name “Doll Derr” – particularly the “Doll” part, which inevitably became “Dolly” or “Dollie” in the jocular hands of sportswriters.9 He never legally shed his father’s last name, and it became more prominent in his activities later in life,10 but he achieved his greatest sporting successes under his mother’s family name. His adopted nom de guerre stuck with him, and he with it: As late as 1969, if you wanted to find Luther Derr Sahm in the Baltimore phone book, you had to look under Doll Derr.11

Dozens of professional minor leagues operated across the United States in the early 1910s,12 and it was only natural that a baseball-minded young man would seek a place in one of them. Sahm, described as “one of the best semi-pros in Baltimore,”13 found his way to Raleigh, North Carolina, in July 1913 for a trial with the Raleigh Capitals of the Class D North Carolina State League. “Raleigh had a new outfielder on the job, whose name to a contract reads Doll Derr,” the Raleigh News and Observer reported, with evident skepticism.14 Sahm played four games with the Earle Mack-managed team,15 collected one hit, and was released. “Derr may be a ball player, but he has never shown any signs around this territory,” the News and Observer summarized.16

Sahm’s next recorded flirtation with professional baseball came the following year when he scouted for Jack Dunn, the celebrated owner and manager of the Baltimore Orioles of the International League, whose discoveries over the years included Maryland-born legends Babe Ruth and Lefty Grove. News reports credited Sahm with signing several players for Dunn, though 21st-century records do not list any of them as having played for Baltimore.17 Fourteen years later, Sahm joined a throng of notables attending Dunn’s funeral.18

Sahm, not yet 24, started his path to the majors in the summer of 1915. News stories in late July reported his signing as an umpire with the Class D Blue Ridge League, a six-team circuit with teams in Maryland, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia.19 His first summer appears to have been a trial by fire. At various points, newspapers criticized the young arbiter for his “inexperience and lack of backbone,” blasted him as “entirely lacking in nerve” and “a miserable failure as an umpire,” and described him as “as bad as usual, which is rancid.” He was criticized for making premature calls, and was showered with empty bottles on at least one occasion.20 On the last day of the season, he reportedly switched places with a player and played center field for the Martinsburg, West Virginia, team for several innings as part of the hijinks of a farcical game.21

The hard knocks continued, off and on, for several years. While working in the Potomac League in 1916, Sahm was punched by Frostburg (Maryland) second baseman Mike Boyle, who was fined $10 and suspended for 10 days.22 A player on the Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, team struck him the following season, drawing five days’ suspension and a $15 fine from a judge.23 In 1920, working in the International League, Sahm took several punches from Jersey City pitcher Fred Harscher and then swung on him in response; Harscher was arrested.24 And in Toronto in 1921, the umpire was spat on by players and again showered with bottles by fans.25

And yet, Sahm made progress. The papers that blasted him early in his career praised him, a year or two later, for doing well.26

World War I interrupted his forward motion. Drafted in 1917,27 he served in France in the 58th Coast Artillery.28 “The terrors of battle were a joke to him, for he has umpired hundreds of baseball games,” a reporter quipped.29 Returning to civilian life, he advanced through the New York State League and the Southern League to the International, one step below the majors, in 1920.30

The 1922 season proved to be pivotal for Sahm, off and on the diamond. In June, he married Evelyn Louise Myers in Ellicott City, Maryland.31 And at season’s end, IL President John Conway Toole selected him as the IL umpire to work the Little World Series between Baltimore and St. Paul, seen as proof that Sahm was the league’s best ump.32 After making a key call against St. Paul in the final game of the series, Sahm again had to push his way through an angry crowd to safety.33 But the Baltimore Sun – a supporter of Sahm throughout his career – predicted bright things in his future: “Derr umpired wonderful ball in this series. He’s class all the way through, and it is very likely he will be advanced to the big leagues this winter.”34

Sahm, just 31, was poised to break through in 1923, starting with seemingly wonderful news at home. On March 15, the Baltimore Sun reported the birth of a son, Luther D. Sahm, to the umpire and his wife three days earlier. “He weighs nine pounds and is feeling fine, thank you,” the Sun reported jauntily.35

Sahm, just 31, was poised to break through in 1923, starting with seemingly wonderful news at home. On March 15, the Baltimore Sun reported the birth of a son, Luther D. Sahm, to the umpire and his wife three days earlier. “He weighs nine pounds and is feeling fine, thank you,” the Sun reported jauntily.35

Unfortunately, the report proved off-base. Subsequent news articles about Sahm never again mentioned his son, and a search of cemetery listings finds the grave of an “Infant Sahm,” born and died in March 1923, in Baltimore’s Loudon Park Cemetery.36 On the verge of his biggest professional triumph, Sahm suffered a deep personal loss. He’s not known to have discussed it, but it seems possible that during the crucial months of April and May 1923 – when he was trying to convince the National League that he was big-league material – he had something much weightier on his mind than baseball. One wonders whether his personal loss affected his professional performance.

His promotion to the NL, replacing Cy Rigler,37 was announced in mid-April, a few days before the season started. Most news reports did not describe the hiring as a tryout, but Sahm sounded a cautionary note, telling the Baltimore Sun that he “hoped to stick” in the majors. He was paired with the legendary Bill Klem and assigned to begin his career on April 17 , Opening Day at Braves Field, as the Boston Braves took on the New York Giants.38

Sahm worked his first 12 games alongside Klem, umping exclusively on the basepaths while the older arbiter handled home plate. On April 29 he was reassigned to work with former Federal and American League ump Barry McCormick His 14 games with McCormick included six appearances behind the plate. Sahm worked his final two games, on May 17 and 18, on the basepaths as part of a three-man crew with Charlie Moran and Bill Finneran. That was it for Sahm’s big-league career; by June 2, he was back in the International League.39

Why? The Baltimore Sun hinted sensationally that the “most unusual” circumstances of Sahm’s departure “will probably never be made plain to the fans.”40 IL president Toole offered a clearer explanation: Sahm had been a “victim of circumstances,” his career doomed by an inability to get along with Klem.41 The Sporting News noted, but did not explain, Sahm’s departure in a brief news item with the droll headline “Doll Derr Didn’t Do.”42

Sahm was reportedly under consideration by the American League in the 1926-27 offseason but was passed over without public explanation.43 His only exposure to the majors after that came in exhibitions. In March 1929, Brooklyn Robins manager Wilbert Robinson asked Sahm to umpire his team’s spring training games.44 And in April 1930, Sahm worked behind the plate for an exhibition between the Philadelphia A’s and Baltimore Orioles – the latter, of course, still a minor-league team in the IL at that point.45

His 1929 spring-training work for the Robins produced a curious news story in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Sahm discussed a spring game in which he blew a call with Klem in the stands. He’d called a runner out on a force play because he hadn’t seen the fielder drop the ball. “To think that I pulled such a bone with the best umpire in the business looking at me,” Sahm lamented. The writer didn’t mention – presumably because Sahm didn’t tell him – that Klem and Sahm had been partners six years earlier, and that Klem’s apparent disapproval was the reason Sahm wasn’t still in the majors.46

Sahm’s minor-league career continued until 1931, marked by more ups and downs. He missed portions of the 1924 and 1925 seasons due to illnesses – his own and in his family – and was reportedly “discontented” in the IL in 1925.47 The latter issue was resolved in unusual fashion that July when the presidents of the IL and American Association arranged a straight-up umpire trade, with Sahm going to the AA in exchange for arbiter Gerald Hayes.48

Sahm was embroiled in still another fan riot while working in the AA two seasons later. In the first game of a doubleheader on September 5, 1927, Sahm called a close, game-ending play against the Toledo Mud Hens – one of several disputed calls Sahm made against Toledo that season. Toledo manager Casey Stengel raged at the ump, and several hundred fans came out of the grandstand to menace him. Sahm avoided serious injury but was confined to his hotel room after the game; a local umpire replaced him for the nightcap.49 The following spring, he requested his release from the AA and didn’t umpire at all that year, resurfacing in 1929 for a final three-season stint in the IL.50

Sahm suffered additional personal losses in the years following his brief big-league stay. His grandfather, Luther C. Derr, died in November 1925; Sahm returned to Frederick to serve as a pallbearer.51 And in November 1928, his wife was granted a divorce and custody of the couple’s four-year-old daughter, also named Evelyn. A news article quoted Mrs. Sahm as saying her husband treated her like “a housekeeper and a cook,” and provided her with little money while buying “shirts by the dozen” and “as many as four hats at a time” for himself.52

The announcement of Sahm’s divorce notably described him as a “former professional baseball umpire, now connected with the State Motor Vehicle Department.” After giving up umpiring for good, Sahm built a second career in Maryland’s motor vehicle department – one that found him finally performing for receptive crowds.

A 1937 news story described Sahm as one of three clerks working for the Commissioner of Motor Vehicles, serving as “major-domo of the rows and rows of tag storage bins in the basement” – overseeing distribution of license plates throughout the state.53 A far cry from mingling with Kenesaw Mountain Landis and Christy Mathewson on the field on Opening Day 1923, to be sure.54

But that was only part of his role. Sahm joined the safety department of the Commissioner of Motor Vehicles’ office and undertook a series of vehicle and bicycle safety lectures to community groups. The speeches took him across Maryland and, at least once, into neighboring Delaware.55 He also was involved in a successful effort to pass a statewide school bus safety law: When school buses stopped, motorists traveling in either direction were required to follow suit.56 By the mid-1940s, he was being described as “director of safety education.”57

His vehicle safety work brought out talents in Sahm that are not otherwise mentioned in the public record. A 1936 Maryland publication targeting the state’s deaf residents mentioned that Sahm was “adept in the use of the manual alphabet,” having participated in boyhood athletic events with teams of deaf boys.58

Sahm also produced a series of traffic safety movies – some, though not all, aimed at children. He incorporated the films into his lectures and distributed them for showing by schools, churches, parent-teacher organizations, and other groups.

The 45-minute “The Cavalcade of Wheels,” which outlined a well-regarded bicycle safety program in the city of Cumberland, won an award for practical filmmaking from the Amateur Cinema League in 1944.59 An earlier film, the half-hour “Safety for the Schools of Maryland,” had been shown about 100 times and seen by at least 10,000 people despite limited publicity.60 Other titles reportedly produced and shown by Sahm included “Stop, Look, and Live” and “Making Your City Safe.”61 Although one scene in “The Cavalcade of Wheels” featured a bicycle rider wearing “a monstrous and fearsome death’s head, constructed by Mr. Sahm from papier-mache,” Sahm emphasized that his movies did not seek to frighten or shock: “The public is tired of gruesome safety pictures.”62

In his spare time in the 1940s, Sahm organized and led an American Legion junior baseball league in Baltimore, with support from Jack Dunn’s widow and son.63 He also earned praise for supporting sports programs at the Cheltenham School for Boys, a reform school housing Black youth.64 A marriage certificate issued in Arlington, Virginia, indicates that Sahm remarried in November 1945 to 27-year-old clerk Helen Elizabeth Norris. The marriage appears to have been short-lived: The 1950 Census describes Sahm as married, but does not list his wife as living with him.65 Helen Sahm is listed as divorced in the same census, living with her mother and sisters elsewhere in Baltimore.66

News references to Sahm thin out in the 1950s and ‘60s. Obituaries indicate that he worked for a time as a betting clerk at two Maryland horse-racing tracks.67 In his final years, he moved to a building called the Hopkins Apartments at 3100 St. Paul Street in Baltimore68 – only about a mile from Memorial Stadium, where the major-league Orioles had become one of the AL’s most consistently competitive teams.69 There’s no firm record of Sahm making the short trip to the ballpark. But if he’d wanted to spend his silver years immersing himself in well-played baseball, he would have been hard put to find a better place to live.

Four days after the Orioles clinched victory in the 1970 World Series, Sahm’s life came to a tragic and unexpected end. According to news reports, in the early hours of October 19, 1970, Sahm was sleeping in his parked Volkswagen near the Hopkins Apartments when 15-year-old Charles R. Meadows of Baltimore entered the car to see what he could steal. Sahm awoke during the robbery attempt, and the boy – wearing rings with large metal nuts attached to them – beat him brutally, causing a broken neck and fractured larynx. Sahm’s lifeless body, missing his wallet and personal papers, was discovered at about 9 a.m. by a woman pulling into a nearby parking spot.70 He was about a month shy of 79 years old and was survived by his daughter, Evelyn, and three grandchildren.71 Meadows was convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to life in prison in April 1972.72

Sahm’s former partner Klem has been credited with developing the inside chest protector that gradually replaced outside “balloon” protectors for umpires.73 But the author of Sahm’s Baltimore Sun obituary, doubtless working from a “clip file” of old news items, gave much space to recapping a 1924 Sun story in which Sahm displayed an inside chest protector of his own devising.74 Wire-service rewrites of the obit further played up this angle75 to the point of giving Sahm a posthumous promotion – from the inventor of a chest protector for umpires, to the inventor of the chest protector for umpires.76 Klem, who had died in 1951, might not have been amused.

Sahm’s brief obituary in The Sporting News mentioned neither the chest protector nor his major-league service. Like the Baltimore obituary, it bade him farewell using the name he’d adopted 60 years earlier, before the start of most of his life’s adventures. The “Bible of Baseball” noted that Sahm had “umpired in the minors for many years under the name of Doll Derr.”77

Acknowledgments

This article was reviewed by Rory Costello and Jake Bell and fact-checked by Mark Richard. The author thanks Lynn Blumenau for assisting with research on Ancestry.com.

Notes

1 For consistency, this article refers to its subject as “Sahm” throughout, since Luther Derr Sahm remained his given name throughout his life.

2 “Sahm-Derr,” Frederick (Maryland) News, November 5, 1889: 4.

3 Engraving: “A Handsome Present,” Frederick News, December 9, 1885: 3; “A Handsome Testimonial,” Frederick News, September 16, 1886: 3. Pen art: “Handsome Pen Work,” Frederick News, June 7, 1887: 3. Marken & Bielfeld: “You and Your Friends,” Frederick News, October 10, 1887: 3; Monica Main, “Marken & Bielfeld Printers Started in a Tent in 1880s,” Frederick News, June 17, 1970: C12.

4 “Luther C. Derr, 80, Former Sheriff, Dead,” Frederick News, November 28, 1925: 5.

5 “Divorce Granted,” Frederick News, August 6, 1894: 3.

6 Author’s U.S. Census research via FamilySearch.org, December 2022. In the 1910 Census, the future Doll Derr is listed as “Derr Sahm,” and described as an 18-year-old employed laborer. The name “Derr Sahm” was also used for the young man in a few local news stories, including “Arbor Day Exercises,” Frederick News, April 12, 1901: 3.

7 “M.A.C. Beats Frederick,” Baltimore Sun, November 25, 1910: 12; “M.A.C. Has Hard Task,” Baltimore Evening Sun, November 25, 1910: 8. Football in 1910 was an altogether more primal and brutal proposition than its 21st-century equivalent.

8 Basketball: “Y.M.C.A. Wins in Slow Game,” Frederick (Maryland) Post, January 11, 1911: 7; “pretty catches”: “Locals Victorious,” Frederick News, May 15, 1911: 3; high jump: “H.S. Athletes Win,” Frederick News, May 1, 1911: 5; basketball refereeing: “Exciting Game Ends in Victory for Frederick,” Frederick Post, January 12, 1912: 2.

9 The author could not find a news story with an explanation, and at the time this biography was written, the Baseball Hall of Fame did not have a clipping file for either Doll Derr or Luther Derr Sahm. Author’s correspondence with the Giamatti Research Center at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, December 2022.

10 During his public speaking work with the Maryland Commissioner of Motor Vehicles’ office, detailed later in this story, he was often described in news stories as Luther D. Sahm or Doll Derr Sahm.

11 The Library of Congress has digitized the Baltimore white pages from November 1960 and November 1969, and both include listings for Doll Derr.

12 Baseball-Reference lists 43 major and minor professional leagues in operation in 1913. Accessed December 21, 2022.

13 “Make It Three from Hornets,” Winston-Salem (North Carolina) Journal, July 19, 1913: 7.

14 “Hornets’ Stingers Woefully Weak,” Raleigh News and Observer, July 19, 1913: 3.

15 Earle Mack had had cups of coffee as a player with his father Connie’s Philadelphia A’s in 1910 and 1911, and would have another in 1914. He managed part or all of nine seasons in the minors, then spent 26 seasons as a coach and fill-in manager with the A’s between 1924 and 1950.

16 “Diamond Dust,” Raleigh News and Observer, July 24, 1913: 3.

17 These included shortstop Warren Dean; first baseman Ira Hoch; and pitchers Hop Geohagen, Earl Howard, Karl Howard, and Bill “Shanks” King. “Reds are Full of Fight,” Baltimore Sun, August 22, 1914: 8; “Looks to Greater League Next Year,” Frederick News, September 9, 1914: 7; “Birds Sign Three Good Youngsters,” Niagara Falls (New York) Gazette, September 11, 1914: 6; “Seven Tri-City League Stars with Baltimore,” Frederick News, October 19, 1914: 7.

18 “Body of Jack Dunn Borne to Last Rest,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 26, 1928: 22. Other notables at the funeral included Connie Mack; former Orioles and Philadelphia A’s shortstop Joe Boley; Washington Senators owner Clark Griffith; International League president John Conway Toole; future National League president Warren Giles; and Theodore McKeldin, then a secretary to Baltimore Mayor William Broening, later mayor of Baltimore and governor of Maryland.

19 “Blue Ridge League Releases Umpire,” Washington Post, July 29, 1915: 9; “McAtee May Go,” Adams County News (Gettysburg, Pennsylvania), July 24, 1915: 1. The latter story indicated that Sahm had done well for himself in “the C. and G.C. circuit,” a reference to a local league called the Cumberland and George’s Creek League. “Derr Ump in Local League,” Frederick News, July 22, 1915: 3.

20 “Outrageous Hoodlumism,” Franklin Repository (Chambersburg, Pennsylvania), August 10, 1915: 4; “Hanover Rough Necks Disgust Local Fans; Umpire Has No Spine,” Chambersburg (Pennsylvania) Public Opinion, August 10, 1915: 1; “Lacerating Exhibition,” Franklin Repository, August 24, 1915: 4.

21 “Settled in the Cellar,” Franklin Repository, August 27, 1915: 1.

22 “Derr Attacked,” Adams County News, July 15, 1916: 6.

23 “Continue Losing to Martinsburg,” Gettysburg Times, July 7, 1917: 3.

24 “Derr in Fist Fight,” Frederick News, September 7, 1920: 3.

25 “Orioles Win amid Flying Pop Bottles,” Baltimore Sun, May 6, 1921: 10.

26 “Fancy Game from Raiders,” Franklin Repository, May 22, 1917: 1.

27 “Derr Drafted,” Gettysburg (Pennsylvania) Times, July 23, 1917: 1.

28 Three days after Sahm’s death, the Baltimore Memorial Barracks No. 2047 of the Veterans of World War I took out a memorial newspaper notice in his honor. Death notices, Baltimore Sun, October 22, 1970: C13.

29 Vincent de P. Fitzpatrick, “Looks Blue for F Boys,” Baltimore Sun, May 1, 1919: 3. This article reported that Sahm was considering leaving baseball for the automobile business.

30 “Seven Umps Are Lined Up,” Memphis (Tennessee) Commercial Appeal, March 10, 1919: 12; “Doll Derr Int Umpire,” Baltimore Sun, January 29, 1920: 9.

31 “Doll Derr Will Not Have to Call ‘Em Alone,” Baltimore Sun, June 19, 1922: 9.

32 “Doll Derr to Work Series,” Baltimore Evening Sun, September 26, 1922: 20.

33 “Small Riot Follows Oriole-Saint Game,” Syracuse (New York) Journal, October 16, 1922: 14.

34 Fred Turbyville, “Derr Going Up,” Baltimore Evening Sun, October 16, 1922: 18.

35 “Doll Derr is Father of Bouncing Boy,” Baltimore Sun, March 15, 1923: 15.

36 FindAGrave.com listing for Infant Sahm, accessed December 21, 2022.

37 Rigler’s retirement was temporary; he returned in 1924 and remained an NL ump through 1935. He died in Philadelphia in December 1935, fewer than three months after working his final game.

38 C. Edward Sparrow, “Doll Derr Product of the Blue Ridge,” Baltimore Sun, April 14, 1923: 11; C. Edward Sparrow, “Joe Kelley to Join the Yanks Today,” Baltimore Sun, April 15, 1923: 17. The Sun noted that Sahm’s promotion gave Frederick, Maryland, two umps in the majors: American League ump Dick Nallin, born in Pennsylvania, made Frederick his home.

39 Don Riley, “Reading Fans to Invade City,” Baltimore Sun, June 3, 1923: 18. Incidentally, Sahm ejected two people during his brief big-league tenure – Boston Braves shortstop Larry Kopf on May 15 and Pittsburgh Pirates manager Bill McKechnie on May 17, both for arguing calls on the bases.

40 Fred Turbyville, “Doll Derr Best Umps We’ve Had,” Baltimore Evening Sun, June 1, 1923: 32.

41 Fred Turbyville, “Doll Derr Back in International League,” Baltimore Evening Sun, May 30, 1923: 20. Three years later, a Delaware newspaper provided the same explanation, mentioning that Derr “had a brief experience in the National League, but didn’t seem to suit Klem, who he paired up with.” Roy Grove, “Sport A La Carte,” Wilmington News Journal, November 6, 1926: 14.

42 “Reading Basking in International Sun,” The Sporting News, June 7, 1923: 3. The “Doll Derr Didn’t Do” headline is in a subsection of this article.

43 Leo Doyle, “Sport Topics,” Baltimore Evening Sun, November 12, 1926: 35.

44 Lee Scott, “Billy Rhiel May Win Second Base Job from Jake Flowers,” Brooklyn Citizen, March 5, 1929: 8; “Robins Pick Doll Derr to Umpire Spring Game,” Baltimore Sun, March 9, 1929: 10. The stories do not explain why Robinson sought out the umpire, but multiple explanations are possible. Eleven of Sahm’s 28 major-league games involved the Brooklyn team, and perhaps Robinson admired his work. Both men were also adopted Baltimoreans, and they might have met in the city’s sporting circles.

45 “The Camera Went Click … And Caught This” (photo and caption), Baltimore Sun, April 14, 1930: 26. The Orioles became a major-league team in 1954 when the St. Louis Browns moved to Baltimore.

46 Thomas Holmes, “Poker Banned as Pastime of the Robins This Season,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, April 5, 1929: A6.

47 “Umpire Gets Vacation,” Cincinnati Enquirer, July 8, 1924: 9; C. Edward Sparrow, “Sports Gossip,” Baltimore Sun, April 14, 1925: 14; Charles Houck, “Doll Derr Likely to be Transferred to Another League,” Baltimore Evening Sun, May 26, 1925; 26.

48 “Minor League Umps Figure in Trade,” Los Angeles Evening Express, July 27, 1925: 17.

49 Associated Press, “Umpire Derr Roughly Handled by Fans at A.A. Game in Toledo,” Minneapolis Morning Tribune, September 6, 1927: 14; Robert Creamer, Stengel: His Life & Times (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1984): 176.

50 W.A. Biggs, “Here and There in Sports,” Baltimore Sun, April 17, 1929: 17.

51 “Funerals,” Frederick Daily News, November 30, 1925: 5. Sahm is listed in this item as “Derr Sahm,” a name not seen in print since his youth.

52 “Ill-Treatment Plea Brings Wife Divorce,” Baltimore Sun, November 8, 1928: 48. Whether Sahm’s absence from baseball in 1928 was related to the failure of his marriage is conjecture.

53 Lee McCardell, “Maryland’s Game of Automobile Tag,” Baltimore Evening Sun, October 15, 1937: 50. Interestingly, Sahm gave his address in the 1940 and 1950 Censuses as 2109 Guilford Avenue, Baltimore. News stories from the period give the motor vehicle department’s address as 2100 Guilford Avenue, which means the old ump had only to cross the street to report to work. In the 1940 Census, Sahm gave his occupation as “clerk;” by 1950 he had been promoted to “supervisor.”

54 The ceremonies for Opening Day at Braves Field in 1923 included Mathewson in his then-new role as president of the Braves. Massachusetts Governor Channing Cox and Boston Mayor James Michael Curley also participated in pregame ceremonies.

55 An appearance in Delaware is described in the Delmar New Century Club roundup in the Wilmington (Delaware) Journal, October 18, 1939: 15. The item misidentifies Sahm as “Doer Derr Sahm.”

56 “Auto Trade Notes,” Baltimore Sun, March 31, 1940: 10.

57 “Exhibit Promotes Cycling Safety,” Baltimore Sun, November 14, 1943: Section 1: Page 8.

58 The Maryland Bulletin, May 1936: 143. Made available online by the Maryland State Archives.

59 Award: “State-Made Film Lauded,” Baltimore Sun, February 2, 1944: 17. Background on film: “ ‘The Cavalcade of Wheels’ Portrays Perils of Cycling,” Baltimore Sun, May 20, 1942: 20; Mike Amrine, “Cycling Safety Taught with Film,” Baltimore Sun, May 31, 1942: Section 2: Page 4.

60 “Safety Film Well Received,” Baltimore Sun, April 12, 1936: 10.

61 “Meeting in Interests of Road Safety,” Worcester (Maryland) Democrat and the Ledger-Enterprise, October 6, 1939: 1. Unfortunately, online searches by the author in December 2022 found no indication that any of Sahm’s films have been digitized.

62 Amrine, “Cycling Safety Taught with Film.”

63 Paul Menton, “Orioles Setting Sharp Swat Pace,” Baltimore Evening Sun, April 27, 1940: 8; “Oriole Owner Sponsors Legion Juniors” (photo and caption), Baltimore Sun, May 7, 1940: 18.

64 “Cheltenham Gets Trophies,” Baltimore Sun, October 12, 1948: 10. As of December 2022, the facility was still open, housing young men and women of all races, and known as the Cheltenham Youth Detention Center. Information on its history from Nelson Hernandez, “Parents, Activists Demand Youth Facility’s Closure,” Washington Post, posted June 22, 2003, and accessed December 22, 2022.

65 Census research via FamilySearch.com, conducted in December 2022.

66 1950 Census record for Helen Sahm, via 1950Census.archives.gov, accessed December 30, 2022.

67 “Luther D. Sahm; Was an Umpire,” Baltimore Evening Sun, October 22, 1970: A10.

68 The December 1969 Baltimore phone book cited above lists his address as the Hopkins Apartments, as do news articles about his death.

69 The address of Memorial Stadium was 900 E. 33rd Street; distance from there to the Hopkins Apartments calculated using Google Maps.

70 George Hanst, “Youth, 17, Convicted of Slaying Ex-Umpire,” Baltimore Evening Sun, April 8, 1972: 18; “Body of Man Found Shot in Car on Lot,” Baltimore Evening Sun, October 19, 1970: C20.

71 Sahm’s daughter, Evelyn Sahm Rowland, died in Easton, Maryland, in 2020. “Evelyn S. Rowland,” Easton (Maryland) Star-Democrat, September 6, 2020: A8.

72 George Hanst, “Umpire’s Slayer Gets Life Term,” Baltimore Evening Sun, April 29, 1972: 4. At the time this article was written in December 2022, an inmate search website indicated that Charles Meadows was approaching his 68th birthday and still incarcerated in Maryland’s Jessup Correctional Institution.

73 David W. Anderson, “Bill Klem,” SABR Biography Project. Klem’s page on the Baseball Hall of Fame website also credits him as the first umpire to wear a chest protector. Both pages accessed December 22, 2022.

74 Original chest protector story: Charles Houck, “New Protector – Not an Armor Plate,” Baltimore Evening Sun, April 19, 1924: 13. Unbylined obits mentioning the chest protector: “Luther D. Sahm Services Today,” Baltimore Sun, October 22, 1970: A17; “Luther D. Sahm; Was an Umpire.”

75 A sample headline from the Bridgeport (Connecticut) Telegram of October 23, 1970, which ran an Associated Press summary of the story: “Sahm Dies; Introduced Ump Chest Protector.”

76 In his research for this biography, the author did not uncover any publicity or news coverage given to Sahm’s invention beyond the 1924 Baltimore Evening Sun article and the 1970 obituaries. While Sahm was clearly a forward thinker and might have inspired other umps to advance their own ideas, he does not appear to deserve credit as the lead developer or popularizer of the inside chest protector.

77 “Obituaries,” The Sporting News, November 7, 1970: 54.

Full Name

Luther Derr Sahm

Born

November 22, 1891 at Frederick, MD (US)

Died

October 19, 1970 at Baltimore, MD (US)

Stats

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.