Frank Saucier

At age 25, after becoming the best hitter in three different minor leagues – preceded by two-years’ service as an officer in the US Navy – Frank Saucier was the St. Louis Browns’ most sought-after and anticipated post-World War II rookie since the club signed future 20-game-winning pitcher Ned Garver and slugger Roy Sievers, the American League’s first Rookie of the Year, in 1949.1

At age 25, after becoming the best hitter in three different minor leagues – preceded by two-years’ service as an officer in the US Navy – Frank Saucier was the St. Louis Browns’ most sought-after and anticipated post-World War II rookie since the club signed future 20-game-winning pitcher Ned Garver and slugger Roy Sievers, the American League’s first Rookie of the Year, in 1949.1

On August 19, 1951, against the visiting Detroit Tigers, the left-hand-hitting Saucier, starting in right field, was headed to home plate in the bottom of the first inning in the second game of a doubleheader in Sportsman’s Park, when his and baseball’s world came to a shocking standstill. Why? The phenom outfielder, suffering from an injured shoulder and severely blistered hands, had suddenly been removed from the game by the public-address announcer, making the 6-foot-1, 180-pound Saucier the most famous major-league leadoff batter never to step into the batter’s box for one unprecedented reason: his replacement was 3-foot-7, 26-year-old showman Eddie Gaedel, the most famous and shortest-lived Brownie rookie never to swing a bat.2

Their walks of fame past each other became one of the most storied strolls ever in a big-league game. The result for Saucier was a laughable few minutes from the bench, and for Gaedel, a statuesque squat in the right-hand batter’s box that led to an unforgettable photograph and zany free pass to first base. Only Little Eddie’s boss-for-a-day, Browns owner Bill Veeck, could conjure the wacky scheme he needed to excite the Sunday afternoon crowd of 20,299 (18,369 paid), the largest of the year.3 No ballpark gag was ever too extreme for Veeck, baseball’s sideshow impresario, whose Browns were wading through another lackluster season, buried in the American League basement and on their way to losing 102 games. Veeck’s bit of “dog days” theatrics was a dandy, despite his Browns losing both games, 5-2 and 6-2.4

Gaedel’s one official plate appearance was more a speed bump than a milestone along baseball’s endless highway of significant events. Veeck’s circus act in the second game is one of the twentieth century’s most laughable sports comedic moments, eventually resulting in a major-league rules change prohibiting midgets, contract or no.5 Years later, an online story in bleacherreport.com listed Gaedel’s official at-bat as number 98 in its list of 200 events that “defined, shaped and changed major-league baseball.” Saucier’s reaction: “Maybe, or maybe not. It might have cost me a time at bat,” Saucier recalled in his memoir, “but Eddie’s antic remains the funniest thing I ever saw, in or out of baseball.”

Crouching in front of Detroit catcher Bob Swift to further shrink his strike zone, Gaedel drew a walk on four straight pitches from amused and confused right-handed pitcher Bob Cain.6 Hard as he tried, Cain never sniffed the strike zone, becoming part of an asterisk incident never to be repeated in a major-league game. Gaedel made it to first base, gave way to pinch-runner Jim Delsing and tipped his hat to the crowd. When the laughter died, so did Veeck’s last-ditch effort to elevate the Browns to any level of respectability. American and National League club owners, both league presidents and the commissioner’s office railed at Veeck’s production that afternoon, banning Gaedel from the game and warning Veeck never again to make a mockery of professional baseball.7

Unknown to Veeck, his stunt meant the beginning of the end of the St. Louis Browns. American League owners began to apply every pressure possible to get Veeck out of baseball. They succeeded. Under duress, Veeck sold the club, and after the 1953 season, the Browns moved to Baltimore and became the Orioles. The Veeck-Gaedel “Midget Caper” was, however, neither the beginning nor end of Francis Field “Frank” Saucier, born on May 28, 1926, on a 160-acre farm outside Leslie, Missouri, 60 miles southwest of St. Louis. Much more defines his professional baseball, business, and private lives than one crazy afternoon in the westernmost (at the time) major-league ballpark that, like its owners, no longer exists.

Frank was the last-born child of Alexander Von Steuben Saucier and Margaret Isabel (McGee) Saucier, a family with roots reaching back to French pioneers who had been in North America since 1660. A youthful Frank studied the rudiments of baseball by watching his four brothers and sister play the game. Living near to St. Louis later brought both National League Cardinals and American League Browns games on radio into the Sauciers’ farmhouse. They were the only big-league clubs at the time to play all home games in the same ballpark, obviously on different days.

When Frank was 5, the Sauciers moved 15 miles north to own and work a larger farm near the Missouri River town of Washington. There, his much older brother Clay taught him to throw, catch, and hit a ball, immediately becoming his full-time mentor and longtime adviser. “Clay treated me like I was his boy long after my adolescent years,” Saucier recalled. “He was a superb tutor and cared for me greatly. As a teenager, Frank became an accomplished sandlot catcher and all-positions fielder, playing with grown men for several town baseball and softball teams. “When Adolf Hitler marched into Poland on September 1, 1939, I marched into Washington High School, knowing that before I graduated, America would likely be drawn into war,” Saucier wrote in his memoirs.

Washington High had no baseball team, so Saucier became a basketball star. His play and academic accomplishments fetched the attention of Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri, where he accepted a partial scholarship. Without sufficient funds for a full ride, Saucier entered Westminster in 1943 via a different route – the US Navy’s V-12 officer training program. Completing the Navy’s accelerated study and training curriculum, he was able to forgo the college’s undergraduate math and physics curriculum and was commissioned an ensign as World War II in the Pacific wound down. Saucier became a star varsity basketball player and a catcher-outfielder on Westminster’s baseball team. Before leaving campus for his final V-12 program semesters at Notre Dame University in 1944, he batted .519, a Missouri College Athletic Union record. Long after Saucier’s half-season with the Browns, Westminster renamed its ballfield Saucier Field.

After leaving Notre Dame only weeks before his 19th birthday, Saucier volunteered to join Scouts and Rangers, a combat duty group that was a forerunner to the Navy Seals. He sought command and was assigned to train and lead a beach party that would land on Japanese soil. In August 1945, halfway to the Philippines, the group learned that Army Air Force bombers had dropped two atomic bombs on Japan, effectively ending the war. There was still duty to perform. After an uncontested landing on Wakayama Beach, a few miles south of Hiroshima, Saucier made his way there to view the devastation created by the first A-bomb blast on August 6, 1945. He recalled, “I could hardly believe what I saw as my Jeep driver and I approached the bridge leading into the ashes of a city that would become powerfully engrained in history.” Saucier’s postwar duty ended in China as a lieutenant (j.g.) aboard the USS Mount Olympus, an amphibious force command ship. After four months’ service, he returned to America, eager to resume his senior year at Westminster and enjoy a final baseball season. He also hoped for a tryout in Sportsman’s Park, owned by the Browns and leased to the Cardinals. As did Ted Williams and thousands of veterans, Saucier left the Navy with a reserve officer obligation for six years, plus a new and powerful credential: The GI Bill of Rights. Passed by Congress and signed by another Missourian, President Harry S. Truman, the legislation among other things guaranteed veterans funding to pursue a college education; Frank could now complete, tuition-fee, a degree in physics and math.

Years before entering Westminster, Saucier had a business career goal to play professional baseball and accumulate enough capital to become an oil wildcatter somewhere in America’s Southwest. He firmly believed that baseball would be a stepping stone to successful drilling ventures. A construction job supplemented his meager savings, but a roommate’s father, a successful oilman, offered counsel about what it took to find and produce oil at a profit. Until he could make a buck, the aspiring entrepreneur banked the advice. In the spring of 1948, Saucier finished his collegiate baseball season batting .500. Scouts from the Philadelphia Athletics and Browns had been watching, and began calling. St. Louis sent chief scout and management confidant Jack Fournier to arrange a visit, talk about a contract and deliver Frank to Sportsman’s Park and a tryout for Browns manager Zack Taylor and club owners, brothers Bill and Charlie DeWitt. An impressive workout led to a contract offer, which Saucier turned down, explaining that his degree came first, but that he would consider signing after graduating.

Diploma in hand a few weeks later, Saucier agreed to DeWitt’s contract terms to catch for the Belleville Stags of the Class-D Illinois State League. As he returned home to sign his contract, the car in which he was a passenger ran off the road, injuring both the driver and Frank, whose right knee banged into the dashboard. His pal suffered severe facial cuts from broken glass, Shaken, but undeterred, the pair finished the slow trip home to Washington without further incident. Saucier did not tell Charlie DeWitt about the crash and his deep bruise.

After convalescing for several days, the Browns’ newest phenom took a bus to St. Louis with his clothes, spikes, catcher’s mitt, and outfielder’s glove stuffed into one suitcase. Signed and ready for delivery to Belleville by Jack Fournier, they crossed the Mississippi River. En route, Saucier learned that a new young batterymate would soon arrive. Charlie DeWitt had also snagged a 17-year-old local high school phenom for $600 – a flamethrowing righty named Bob Turley.

The five-year age difference between Saucier and Turley benefited both rookies. Turley had never worked with a collegiate catcher, and Frank now had a willing student. At 6-feet-2 and 200 pounds, Turley was raw and wild, according to Saucier, but went the distance in his first start. As the Stags advanced toward the playoffs. Saucier had become the league’s top hitter, aided by 20/10 vision and a reliable swing. He was batting .357 with fewer than 20 regular-season games left and catching righty Mike Blyzka when a foul tip broke his right thumb: Season over.8

“Too bad for Frank, a terrific hitter,” recalled another Illinois State League rookie, scrappy 17-year-old second baseman Earl Weaver, signed by the St. Louis Cardinals to play for the West Frankfort (Illinois) Cardinals. The future Hall of Fame manager would later give Bill Veeck’s extant club the stature Bill so sorely wanted. “(Frank) was hittin’ the hell out of everything and leading the league in batting when he got injured. Broken thumb, I believe.”9 What a memory, without being prompted during an interview nearly 60 years later. Saucier’s thumb healed over the winter to the obvious delight of the DeWitts, who sent him to Florida for spring training as a catcher with its Triple-A Baltimore Orioles club, where he would start the 1949 International League season. Saucier didn’t like early spring East Coast weather and demanded to play in Texas, where the Browns had two teams, the Double-A San Antonio Missions and the Class-B Wichita Falls Spudders. He insisted that his Baltimore salary of some $6,000 also travel to the Lone Star State. The DeWitts agreed to pay the sum, which was far above the organization’s average and $1,000 more than the major-league minimum at the time. With veteran catcher and second-year manager Gus Mancuso already in place at San Antonio, the Missions’ roster was full, so Frank reported to Wichita Falls, close to the oil patches of his dreams.

At Wichita Falls, Saucier dazzled his teammates, winning the Big State League batting title with a .446 average, then the highest-ever mark in the history of Organized Baseball. He had 141 hits in 316-at bats, earning him the Hillerich & Bradsby Silver Slugger Award as the minor leagues’ top hitter. Saucier’s astonishing season landed him at Double-A San Antonio as a full-time left fielder in 1950, despite the DeWitts’ pleas to come to St. Louis. Saucier’s three-part response to their urging in early September settled the issue: San Antonio had a shot at the Dixie Series, the Texas League offered more lucrative contacts with owners in the oil business, and it had better hotels than where the Browns stayed. Frank’s biggest advocates promoting his status quo were Charlie DeWitt and Frank’s skipper, former Browns infielder Don Heffner, “the best manager I ever had.”

Throughout the 1950 season, Saucier was locked in a three-way race for the batting title, finishing with a league-leading .343 average, edging out Fort Worth’s future Hall of Famer Dick Williams and Beaumont’s Gil McDougald, a Yankees farm phenom and soon-to-be American League Rookie of the Year. San Antonio won the Texas League Shaughnessy Playoffs, first sweeping Rogers Hornsby’s Beaumont club in the best-of-seven first round and defeating Tulsa four games to two, earning the right to face Nashville in the Dixie Series. Saucier led his team to that seven-game championship, was named MVP and promptly drove to Niagara Falls, New York, for a honeymoon vacation with Virginia Pullen, whom he’d met while playing in Wichita Falls. Now married, the Sauciers were satisfied through the winter that baseball was in their rear-view mirror, especially when their Oklahoma oil wells were producing high quality crude worth a steady $2.38 a barrel.

Oil and baseball aside in 2020 at age 94, Saucier greatly praised Charlie DeWitt and defended both owner-brothers with regard to spending money where and when they needed it most. “The DeWitts were not cheapskates, as many during my career wrongly described them. They were shrewd, honest business operators, just not with the wealth of the Yankees, Red Sox, and other perennial first division teams. Charlie changed a lot of little things during and after the 1950 season and often traveled with us. We used to carry our own bags from trains and hotels, and Charlie put a stop to that. He didn’t have to, but thought it only right, even when the club was losing money and going South.” By Christmas 1950, still under contract to the Browns, Saucier voluntarily retired from baseball. A week later, he read that The Sporting News had named him Minor League Player of the Year; front-page coverage with his illustrated likeness along that of the Major League Player of the Year, Yankees shortstop Phil Rizzuto. Three weeks later, the Associated Press wrote of Frank, “Saucier, pronounced Sow-Shay, is like a figure in a dime novel. His batting feats during his three years of organized baseball are truly amazing. If he can come anywhere near his minor league marks with the Browns, they may come up with the greatest individual drawing card they’ve had since George Sisler.”10

Despite the notoriety and press focus on the Browns, Saucier declined the DeWitts’ pleas for him to reconsider retirement and report to Browns’ spring training in California. His oil wells were running smoothly and the price per barrel rising. A frustrated Bill DeWitt said that because Saucier would neither renew his contract nor report to camp, he would ask the American League to place him on the ineligible player list.

Saucier explained, “I told Harry Mitauer of the (St. Louis) Globe-Democrat that I’d mortgaged everything I owned and had borrowed considerable money to buy an interest in a wildcat oil well. I’m getting a tidy sum now,” he wrote on April 15, and added that the well was producing about 150 barrels a day. Two days later, Commissioner Happy Chandler wired Saucier that he was ineligible to play for St. Louis. Two months later, North Korea invaded South Korea, beginning a two-year-long war that would take Saucier from spring training into active service in the Navy through 1954.

The route to Saucier’s eventual end as a major leaguer began in July 1951, two days after Bill Veeck bought the club from the DeWitt brothers and a handful of other shareholders. “Shirtsleeve Bill,” so labeled by baseball writers, was desperate to resurrect his fast-fading enterprise. The day before he took over the Browns ownership, St. Louis had dropped an Independence Day doubleheader to the Yankees, leaving baseball’s most flamboyant operator with a fire-sale acquisition, a 21-49 won-lost record and sole possession of the American League basement. Veeck never doubted that Saucier wouldn’t remedy his team’s biggest problem: lack of hitters.

Through much pleading, and knowing that Saucier had missed spring training, Veeck made a wild midnight dash from St. Louis to Washington, Missouri, to persuade him to sign a contract his new boss admitted he couldn’t afford. Saucier waited a day to unretire, agreeing to bring a sorely needed spark to the Browns’ impotent offense. Veeck’s price to accommodate them both was $10,000 and two IOUs, the latter a handsome reserve amount for Saucier while his oil interest continued to flourish. Pitcher Ned Garver, third baseman-outfielder Roy Sievers, and right-handed pitching legend Leroy “Satchel” Paige were the only Browns to earn more money that season.

With the Browns on a road trip, Saucier reported to Sportsman’s Park bringing a badly-injured right shoulder, hurt the previous season in San Antonio. Veeck and manager Zack Taylor rushed him into catch-up batting practice regimes that produced constantly bleeding and scabbed hand blisters. “After the first week in pain, and unable to swing the bat that had brought me back-to-back batting titles, I was never really the same. Having 20/10 vision simply wasn’t enough.” On July 21 he appeared in his first game at home, against the Yankees. After a few more games mainly as a pinch-hitter and pinch-runner, Saucier was in right field on August 19, unaware that he was a half-inning away from his most extraordinary appearance as a professional. His only action afield occurred in the opening frame, when he snagged a chest-high line drive roped by Detroit right fielder Vic Wertz. Then came the Gaedel star appearance. Amid the clamor of such opening-frame antics, not even a well-orchestrated comedy could save the Browns, who lost, 6-2.

Saucier’s hands and right shoulder never healed. He played in eight more games, starting one, and having spot roles in others. His lone big-league hit, a long pinch-hit double in Cleveland’s cavernous Municipal Stadium off Mike Garcia, came on August 7. After his last outfield start, on August 26, 1951, Saucier watched 33 more games from his own and three visitors’ dugouts, a brief but historic time as a Brownie: 18 games, three starts, one hit, four runs scored, one RBI, two pinch-hit walks, one HBP, four strikeouts, and two errors made in the first game he started against the Yankees. Nonetheless, Frank Saucier had accomplished an aspiration to be a major leaguer.

When the New York Yankees and Giants squared off in the World Series, Saucier’s and Veeck’s sights were already on the 1952 season under new manager and St. Louis favorite, Hall of Famer Rogers Hornsby. Frank was familiar with the Beaumont and Texas League All-Star game manager, after a celebratory 1951 season as pilot of the Pacific Coast League champion Seattle Rainiers. The great right-hand hitter, and the last National Leaguer to bat over .400, telephoned Saucier after New Year’s Day and asked him to report early to spring camp in El Centro, California. Hornsby knew Saucier’s batting skills, telling him three days later, “You’re my left fielder.” As Veeck later told Saucier, “If a professional baseball player couldn’t hit at least .300, Rogers – who’d compiled a .358 average over 23 years – wasn’t all that interested in him. I knew that after that first week, he was salivating to begin the season with you in the daily lineup.”

The Browns moved to Burbank to finish preseason work with Saucier and newly acquired slugger Jim Rivera already composing two-thirds of Hornsby’s outfield. Rivera had been Hornsby’s all-everything star at Seattle and hands-down Pacific Coast League MVP and batting champ (.352, 231 hits, 135 runs scored). Hornsby especially needed Saucier and Rivera to carry the Browns offense after former AL Rookie of the Year and Veeck’s only other legitimate .300 hitter, Roy Sievers, went down in El Centro with a shoulder injury, his second since batting .306 in his rookie season, and was never well enough to regain his third-base position. Frank remained confident that he would be in Hornsby’s starting lineup if one looming cloud of doubt was removed: the prospect that as a former active-duty Navy officer with a reserve-duty obligation, he could be recalled at any time during the lengthening and grueling Korean War.

At Burbank and St. Louis in 1951, Saucier unknowingly had been sent orders to report to active duty a month before his 27th birthday. It wasn’t his first notice from Uncle Sam. A locker-room attendant handed him a second telegram from the Navy, forcing Veeck to reveal that he had received and destroyed Saucier’s first recall orders. Frank’s future was cast, and pro baseball would become a thing of the past. When Saucier cleaned out his locker to leave Burbank, Veeck stopped by to explain his peculiar action to hide the Navy’s quest to locate their reservist. Saucier told Veeck, a Marine disabled by accident during World War II service in the Pacific, that his misconduct could have been a prosecutable federal crime. To cover his transgression and without blinking, Veeck told Frank, “I needed you more than the Navy. I needed to protect my investment, especially after Roy’s injury.”

Saucier said goodbye to an embarrassed Veeck, a dejected Hornsby, and his locker mate from the ’51 season, Satchel Paige. He reported to Pensacola Naval Air Station, and for the next two years was put in charge of all preflight administration protocols at Base Headquarters Cadet Battalion. He also played left field for the preflight Goslings, leading them to the Sixth Naval District championship and batting over .500. His final game at Memphis Naval Air Station was also his last ever in flannels. Three months later, as a newly promoted lieutenant, Frank had a visit from Veeck, who in midseason had shed himself of Hornsby, choosing another St. Louis favorite, Marty Marion, to manage the club to the finish line. Veeck came to Pensacola for one reason: to make a hat-in-hand appeal to Navy brass to release Saucier – still his official American League contract player – from active duty to play in 1953.

Saucier said he was shocked at Veeck’s brazen suggestion, reminding him that the Sauciers belonged to the Navy, and halfway through their hitch were still celebrating the birth of their first child, Sara. Again, Frank declared that his baseball career was over. Veeck resisted, saying that if Saucier wouldn’t reconsider going to spring training, he would fly to Washington to meet with Saucier’s “fellow” Missourian, President Harry S. Truman. “Bill was adamant, saying he would stop at nothing to ask the soon retiring commander-in-chief to have me discharged in order to ‘protect my interest.’ I laughed and told Bill that his effort would be wasted time. Truman had six weeks left in office before former five-star General Dwight D. Eisenhower was inaugurated as the 34th president.

“I suggested to Veeck that Truman probably had other things on his mind,” Saucier later wrote. “I thanked Bill, told him I appreciated everything he had done for me and handed him back the two IOUs that he gave me in July of 1951. Bill was surprised, but we both knew he needed the money a lot more than I did. If he ever made good on his effort to see President Truman, I never knew about it. I could only hope that he didn’t.”

Saucier and Veeck never met again. Saucier was released from active duty in April 1954 and, with family in tow, left Pensacola for Texas. The next 38 years were spent in the oil, gas, and chemical industries in Tyler, where son John was born; Pampa; and Amarillo. Virginia died in 2009. She remains the answer to decades-long inquiries about Frank’s greatest thrill in baseball. “Meeting Virginia Pullen in 1949 in Wichita Falls,” he responded unhesitatingly about his baseball, business, and life partner. “The night she said ‘yes’ was the biggest thrill of my life.”

On his 94th birthday, May 26, 2020, Frank Saucier was the lone surviving player in Bill Veeck’s 1951 “Midget Caper.” When the 2019 World Series ended in Houston on October 30, Saucier was one of only 26 living former major leaguers to have served in World War II. Still in Amarillo as of August 2020, he said he looked forward to signing autographs from fans of all ages. Regrets? “None,” he said. “I got to be a major leaguer and invested my Browns money, which fueled my business future. I’m always proud to credit the DeWitt brothers, whose generosity and faith in me led to a good baseball and business life, shared with a wonderful wife, two loving and educated children, and always peace of mind. My cap is always off to those men, the St. Louis Browns, little Eddie Gaedel and of course Bill Veeck, who gave me a second chance to become a big leaguer.”

Postscript

Frank Saucier died at the age of 98 on March 3, 2025.

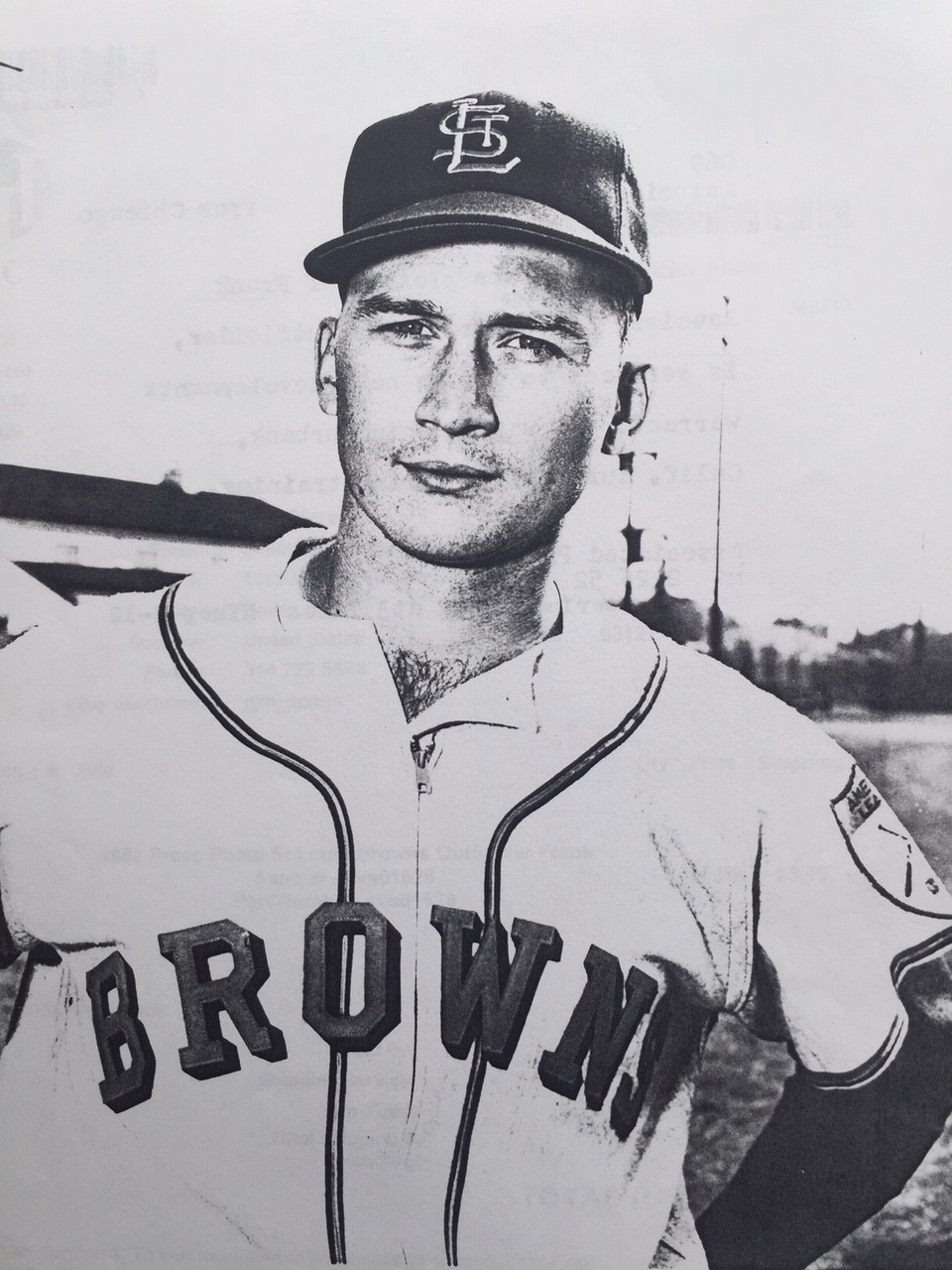

Photo credit

Courtesy of Frank Saucier.

Sources

All direct quotes not otherwise attributed are from interviews with Frank Saucier by the author and from Saucier’s memoirs. In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted Baseball-Reference.com and the following:

Saucier, Frank. My Story (60-page memoir typed in 1997, containing personal recollections, photos and press clippings (many publication datelines and page numbers missing) from the Dallas Times-Herald, Fort Worth Star-Telegram, San Antonio Express-News, Fort Worth Press, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, The Sporting News, Waco Tribune, Wichita Falls Record-News, and Washington Missourian, April 1948-March 1952).

O’Neal, Bill. The Texas League (Austin, Texas: Eakin Press, 1987).

Rapoport, Ron. Let’s Play Two (New York: Hachette Books, 2019).

Interviews

Garver, Ned, October 8, 2009, St. Louis.

Saucier, Frank, multiple from 2006 to 2020.

Sievers, Roy, October 8, 2009, St. Louis.

Weaver, Earl. November 9, 2007, Fort Worth, Texas.

Broeg, Bob, July 28, 2007, St. Louis (SABR 37).

Notes

1 Miles Wolff, ed., The Baseball Encyclopedia, 9th ed. (New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., 1993).

2 Frank Saucier, My Story, memoir, 1997. See also Frank Saucier and Jim Ball, It Wasn’t All About Eddie (unpublished manuscript, 2020).

3 Author interview with Bob Broeg, July 28, 2007.

4 St. Louis Globe-Democrat, August 20, 1951: C3.

5 Bob Broeg, Bob Broeg: Memories of a Hall of Fame Sportswriter (Champaign, Illinois: Sagamore Publishing, 1995).

6 St. Louis Globe-Democrat, August 20, 1951: C3.

7 Bill Rogers, ed., Pop Flies: The Official Magazine of the St. Louis Browns Historical Society, St. Louis, issues from 2009-2015.

8 News-Democrat (Belleville, Illinois), August 4, 1948. At season’s end, he finished second in batting average to Richie Martz’s .361.

9 Earl Weaver interview, Fort Worth, Texas, November 9, 2007.

10 Associated Press, “Browns Have Another Sisler on Way Up from Texas League in Francis Saucier,” Washington Post, January 25, 1951: 18.

Full Name

Francis Field Saucier

Born

May 28, 1926 at Leslie, MO (USA)

Died

March 3, 2025 at Amarillo, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.