Tom Dolan

Who was the only player to play for major league clubs in St. Louis in three different leagues in three successive years? The answer is Tom Dolan, who played for the St. Louis Browns in the American Association in 1883 and 1884, jumped to the St. Louis Maroons in the Union Association in 1884, and then stayed with the Maroons when they moved to the National League in 1885 and 1886. Add in his time with the St. Louis Whites of the Western Association in 1888, and he played for St. Louis clubs in four different leagues over five seasons.

Who was the only player to play for major league clubs in St. Louis in three different leagues in three successive years? The answer is Tom Dolan, who played for the St. Louis Browns in the American Association in 1883 and 1884, jumped to the St. Louis Maroons in the Union Association in 1884, and then stayed with the Maroons when they moved to the National League in 1885 and 1886. Add in his time with the St. Louis Whites of the Western Association in 1888, and he played for St. Louis clubs in four different leagues over five seasons.

Thomas J. Dolan was born in New York on January 10, 1855, to John (born ca. 1820) and Delia (Wheeler) Dolan (born ca. 1827), both immigrants from Ireland.1 Delia (also identified as Bridget in some records, for which Delia is a diminutive) arrived in the United States around 1846. Their first son was born in 1851, and their last in 1859, all in New York. The family (John, Delia and sons Michael, Thomas, Joseph and John Jr.) moved to St. Louis around 1867, when John Sr. begins showing up intermittently in city street directories as a teamster or drayman until his death in 1885. Tom is identified as a porter in 1875, a teamster in 1876, and finally as “base ball” in the 1877 street directory.

Dolan started playing baseball for St. Louis amateur clubs at least as early as 1873, playing center field and catching for a club called the Rivals. By late 1874, he was playing with a new club in St. Louis, the Niagara, where he first became a teammate of Jim “Pud” Galvin. Dolan would catch Galvin over the next few years as both players established a reputation in baseball circles. In 1875, they both returned to the Niagara, but in mid-May, Galvin joined the St. Louis Brown Stockings in the National Association, By the end of the summer, Dolan was playing for a club called the Empire.

In 1876, Dolan and Galvin joined the St. Louis Red Stockings, also known as the Reds. The Reds had played as a professional club in the National Association in 1875 for a couple of months before dropping out. After the National League formed over the winter of 1875-1876, the Reds remained in a looser organization of professional clubs, where they were one of the top teams. According to statistics published in the St. Louis Globe-Democrat after the season, the Reds played 91 games in 1876, winning 67, losing 23 and finishing one in a tie. They won 12 “Chicagos” and were “Chicagoed” six times. (The term “Chicago” was used for a shutout from the early days of professional baseball into the early twentieth century.) Dolan was reported to have played in 83 of those games, scoring 98 runs and getting 139 hits in 388 at bats for a .363 average. His fielding wasn’t as good, as he made 136 errors. His position was given solely as catcher, although it is likely he played elsewhere at times.2

Dolan and Galvin took their show on the road in 1877, signing with the Pittsburgh Allegheny of the International Association.3 The Allegheny played 19 out of a scheduled 24 games in the Association, finishing with a record of 13-6. Dolan played in all of them and finished with a batting average of .154. The club also played against other teams outside their league. Overall, the Allegheny had a record of 29-56.4 Dolan batted .227 and made 130 errors.5 Allegheny originally intended to bring both Galvin and Dolan back for 1878, but in late October they released both players so that the pair could sign with the Buffalo, New York, club (also in the International Association). The Buffalo Sunday Morning News praised the signing: “He [Dolan] has an excellent record as a catcher and also stands high as a batsman, and is to be considered one of the best and most reliable men in the nine.”6

The 1878 Buffalo Bisons were a powerhouse club, winning the International Association championship, and finishing with a winning record against every National League club except league champion Boston.7 Their final record was 85-28-3.8 Twelve of the thirteen players on the roster that season played in the major leagues at some point, most notably Pud Galvin, Davy Force, and Denny Mack In 83 games Dolan batted .159 and fielded .776 behind the plate, worst on the club.. 9Dolan was not retained for the 1879 season, when Buffalo joined the National League. This ended the association with Galvin that had made his reputation as a catcher.

The Buffalo Morning Express wrote about the change in March 1879. “In the constitution of a first-class base-ball nine — a nine that can win pennants, etc. — it is of vital importance, not only that the pitcher and catcher shall be each in his place a scientist of eminent attainments, but that they shall work together in entire union, each thoroughly understanding the other’s peculiarities, habits and temperament, seeing into each other’s souls as it were. In short, the pitcher and catcher should be as the two parts of a perfect machine, automatic in the precision of its action, but inspired with an intelligence which ordinary machinery does not possess.” Then, in the context of an interview with Galvin, the paper wrote, “He was with Dolan five years. Dolan had no head. The latter worthy knew how to stop a ball, but he didn’t know what to do with it after he got it.” 10

Even though Dolan left the Buffalo club, he didn’t leave Buffalo. In February 1879, he married Tillie O’Laughlin at the St. Patrick’s Church in Buffalo. At the time of the 1880 US Census, Tom and Tillie were living in Buffalo with six-month old daughter Jenny, the first of ten kids for the Dolans. The family remained in Buffalo until late 1882, when Dolan would sign with the St. Louis Browns.

Following three years of relative stability, Dolan became a nomad in 1879. He started the season with Utica, an independent professional club, where he caught Tim Keefe in his first professional season. When that club disbanded in July, he signed with Springfield, Massachusetts. He was released at the end of the month and returned to Buffalo, which led to his major league debut. On September 30, the National League Chicago White Stockings were in Buffalo for the final game of their season. Silver Flint, their regular catcher, had returned to Chicago to get married, and Tom Dolan was called upon to catch for Chicago.11 Dolan threw out Chick Fulmer attempting to steal third in the second inning. He finished the game with six putouts, two assists, and one passed ball. At the plate he went 0-for-4. “Considering the fact that Dolan had not played in a long time, he did very creditably,” wrote the Chicago Inter Ocean.12

As a catcher, Dolan played with what was considered an older style. “[Dolan] is of a school of catchers of an older day, he catching as [Bill] Craver did, that is, facing the ball with unyielding hands, and not with the spring-like movement of catchers like Jim [Deacon] White. The result is that he gets a great deal of punishment, and his hands, tough as they are, necessarily give out.”13 As a testament to how tough catching was at that time, while with Utica in May and June of 1879 alone, Dolan suffered a dislocated finger, was hit in the mouth by a foul ball, and then broke a finger.

Over the winter of 1880, the San Francisco Athletics courted Dolan and former battery mate Galvin. Galvin went out to California, but Dolan remained in Buffalo playing in scrimmages during spring training. Finally, Dolan signed with San Francisco, arriving in California at the end of April, just as Galvin was leaving to go back east. Dolan stayed in California for the summer, returning to Buffalo at the end of October. In April 1881, now the father of two, he took a job as a fireman.14

A year later local newspapers campaigned for him to be signed by Buffalo’s National League club for the 1882 season. “He is a far different man in his habits from what he used to be and if given a trial would probably do more brilliant work than ever.”15 Dolan made his season debut catching Hugh “One Arm” Daily, who was making his major league debut at the age of 34 years, 288 days. Daily had lost a hand in a gun accident as a child, and despite this became a professional pitcher with a strong curve and fastball, such that catchers had trouble catching him.

As a third-string catcher, Dolan batted .157 and had a fielding average of .926. Despite that, the St. Louis Browns signed him for 1883, prompting the St. Louis Globe Democrat to comment, “Dolan is a live, wide-awake player, who does some brilliant things, and who will always be a prime favorite, but Dolan has a bad habit of throwing the ball around too freely for his own good, and the long list of errors chalked to his credit is due to an overindulgence of his hobby.”16 Splitting his playing time in 1883 between catching and the outfield, he actually led all catchers with a .957 FA, but his BA of .214 was the third worst in the league.

The Dolan family had moved to St. Louis in November 1882. In January 1884, a handball court was built at Sportsman’s Park. Offseason reports in St. Louis throughout the decade often mentioned ball players playing handball as part of their routine of staying in shape. Dolan, considered one of the best handball players among major leaguers, was made the superintendent of the court.17

Back with the Browns in 1884, he was enjoying his best season to date offensively, hitting .263, but defensively was significantly worse, making 35 errors in 36 games when, in late August, he got into a dispute with Browns owner Chris Von der Ahe over playing time. Dolan was upset he was getting much less time catching than Pat Deasley and was being paid much less than Deasley ($1,600 to Deasley’s $2,500), despite doing “as good work behind the bat and with the stick as Deasley.”18 On August 23, he walked out of Sportsman’s Park after a meeting with Von der Ahe, went over to Union Park, and caught that day for the St. Louis Maroons in the Union Association.19

Henry Lucas, owner of the Maroons, said Dolan told him he had been expelled from the Browns, and thus was not jumping his contract. Von der Ahe denied that Dolan had been expelled, claiming instead that Dolan had left the Browns and refused to play for them anymore, but that the Browns had not given him a release to sign with the Maroons. While the dispute continued, Dolan did not play again until September 1, again with the Unions. He remained with the Maroons the remainder of the season. On September 28, he was given a gold watch, chain, and locket before the game by the Clerk of the House of Delegates as a token of the “friendship and esteem” of his fans.20 Their esteem notwithstanding, Dolan hit just .188 with the Maroons in 19 games.

Following the 1884 season, the Union Association collapsed as the Maroons transferred to the National League. Dolan’s status for 1885, as a contract jumper (along with several other players from the Union Association, including Dave Rowe and Jack Gleason from the Maroons), was subject to the approval of all the clubs in both of the remaining major leagues.

“The case of Tom Dolan, while it will necessarily contain an admission of contract-breaking and an appeal for mercy, has a backing that is influential and powerful, and reveals the fact that base ball affairs exercise even political circles. Tom is very popular in the wards which roll up big majorities for the Hon. John J. O’Neill, and it is now asserted that the latter, who has now an apparently indefinite control of the Eighth Congressional District, will never again be a candidate from that district unless he votes and causes Mr. Von der Ahe to vote, for the reinstatement of Dolan.21

Even with the support of Von der Ahe, these three Maroons remained blacklisted by the American Association for most of the season.22 They received considerable support from the city; between 5,000 and 6,000 people attended a benefit game on June 28 at the Union Grounds between a team of locals organized by the trio (including Joe Murphy pitching) and the local Prickley Ash club. The Blacklisted Nine (as the team was called) won by a score of 8-2. The three played exhibition games under the Blacklisted name for much of the summer against local and area clubs. Rowe was reinstated in mid-September 1885, returning to the Maroons, while Dolan and Gleason were not reinstated until early October.23 Dolan managed to appear in three games for the Maroons as the season wound to an end, barely accomplishing his trifecta of appearing with a major league club for St. Louis in three different leagues in three successive seasons. Ironically, in his first game back, his opposite for the New York Giants was Pat Deasley.

Dolan returned to the Maroons in 1886. He played in just fifteen games through the first two months of the season before being released on June 28 along with Charlie Sweeney. The two players were “guying” one another in loud and abusive language at the park and offended the people in the stands around them. They were both fined $50 and released. Sweeney had been playing poorly, so his release was not a surprise. “The release of Dolan, however, was something of a surprise. He is a fair ball player, and his catching this season had greatly improved.”24 Dolan was hitting .250 at the time of his release. He was signed by Baltimore of the American Association ten days after his release by the Maroons (the minimum time required before a player could be signed after being released). With Baltimore, he was teamed up with Jumbo McGinnis, whom he had caught previously with the Browns in 1883 and 1884. Dolan hit just .152 in 38 games for Baltimore. His fielding was mixed for the season. In 1883 and 1884 he had 87 passed balls in 90 games combined. In 1886 (after missing most of 1885), he had 61 passed balls in 50 games. However, his fielding percentage (.912 across both clubs) was his first season over .900 since 1883.

In March 1887, Dolan was formally released by the Baltimore club. The manager for the Leavenworth (Kansas) club in the Western League offered Dolan and McGinnis $1,800 each for the season, but the two players held out for $2,500 each and did not sign. Shortly afterwards, Dolan was signed by former Maroons teammate Dave Rowe to play for Lincoln (Nebraska) in the Western League. On May 11, Dolan was involved in what may have been the most remarkable game of his career, against Denver in Lincoln. Lincoln fell behind, 3-0, before scoring nineteen runs in the sixth inning. Dolan scored three runs in that inning.25 That same inning, he and Patsy Tebeau (playing third base for Denver) “engaged in an angry brogue and exchanged blows” after Tebeau struck Dolan while putting him out, resulting in a $5 fine for each, according to the Sioux City Journal.26 The Lincoln papers downplayed the incident in the game stories, mostly mentioning Tebeau’s language. “The sluggers slugged Hogan out of the box yesterday in the sixth inning and broke Capt. Tebeau’s heart or hurt something else as it ran out of his mouth in a not very gentlemanly manner.”27 The Sporting News reported on the incident a few days later.

“Tom Dolan, the catcher of the Lincolns became involved in a dispute with Pat Tebeau of Denver. After many loose compliments had been offered by both parties, they fell to blows and both proceeded to pummel each other vigorously. As a result of their pugilistic exhibition they were fined five dollars each, in addition to whatever bruises they may have received in their encounter.”28

This note in the Sporting News prompted a response from the Nebraska State Journal (Lincoln).

“The St. Louis Sporting Life [sic] contains a very unfair account of the alleged fight between Dolan and Tebeau. In the first place, The Journal wishes it distinctly understood that there was no scrimmage, although the Denver man richly deserved a pounding and a heavy fine in addition. In putting Dolan out with the ball he took pains to strike him a terrific blow on the arm. Lincoln’s giant catcher turned to pulverize the little bully, but stopped himself before returning the blow. Dolan had too much respect for himself and the people of this city to engage in a fight on the ball grounds, although the provocation was great. His conduct during the affair was highly satisfactory to our people, albeit there were dozens of men who would have cheerfully paid his fine had he taken Tebeau a mile or so out of the city and given him a sound drubbing.”29

The truth of the incident probably lies somewhere in the middle. Based on reports of Dolan receiving a fine, it seems likely a fight of some type did occur, despite the attempts of the Lincoln papers to downplay Dolan’s role in the incident.

At age 32, Dolan had the best season of his career at the plate with Lincoln. He hit .404 (in a season in which walks counted as hits) in 95 games, third on the club behind Orator Shafer and Jake Beckley. He also hit 10 home runs during the season, his first homers since he had hit a single home run with the Browns in 1883, along with 25 doubles and 17 triples.30 The Lincoln club disbanded in late September. Dolan left for St. Louis “with a hand so badly broken that he will not play again for some time, and he may never find himself able to do his former fine work behind the bat.”31

Over the offseason, Dolan and Lincoln teammates Beckley and Joe Herr signed to play for the St. Louis Whites, Chris Von der Ahe’s new club in the Western Association. While there was speculation during the spring that Dolan would wind up on the Browns, he started the season with the Whites.32 He caught Harry Staley through early June, then moved to the outfield until the Whites disbanded in late June. He was transferred to the Browns, where he played 11 games in his final stint in the majors.

Dolan played for two more seasons in the minors. He signed with the Denver in the Western Association under Dave Rowe for 1889. The western air was good for his hitting, as he again showed power, with 16 doubles (only his second season in double digits), five triples and four home runs and a .263 average in 78 games. In 1890, after getting his release from Denver in February, Dolan signed with Des Moines in the Western Association. He appeared in only 13 games, hitting .288, for the Prohibitionists before he left the club in late June and retired from baseball at the age of 35.33 It is likely that his retirement was hastened by the death of one of his sons (Thomas, Jr., age 2) in early 1890.34 Dolan had a large family by that time; the St. Louis Post-Dispatch described him just one year earlier as “the happiest man on earth when surrounded by his children at his cheerful fireside.”35 By July Dolan had joined the St. Louis Fire Department.36

Dolan remained visible in the baseball scene in St. Louis after retiring as a player. He umpired a few games for the Browns in 1890 and 1891. During the summer of 1892 he played for The Fat Men of St. Louis, a club of players over 200 lbs., against other such clubs from Missouri and Chicago. Dolan’s last reported appearance with the Fat Men was July 3, 1892, playing against the fat men of St. Charles, Missouri. On April 18, 1894, Tom Dolan was back in the headlines of the St. Louis newspapers, but not for his accomplishments as a ball player. While responding to a fire at a stable behind 2737 Thomas Street, Dolan stepped on a live wire and was electrocuted. His crew rescued him after throwing a rubber coat over him to protect themselves from the shock. Shortly after his rescue, another fireman, William Gannon, was killed by the same wires. It was thought that Dolan would die, but he recovered, although not to full health.37

Dolan continued his career as a fireman after the accident, ultimately spending 21 years associated with Engine Company No. 22 in St. Louis. His youngest daughter, Florence, was born in 1899. He fell ill in late 1912, suffering from complications of cirrhosis and pulmonary issues, and after three months he died on January 16, 1913, just days after his 58th birthday. He was survived by his wife Tillie, six daughters, and two sons. Thomas Dolan was buried in Calvary Cemetery in St. Louis, Missouri, sharing a plot with his wife (Tillie died in 1929), young son Thomas, and parents (mother Delia died in 1902).

Afterword

Baseball-Reference identifies Dolan as playing for the Portland Webfeet in the Pacific Northwest League (one game) and Oakland Morans in the California Central League in 1892. The name Dolan appears in the box scores for three games (July 31, August 7 and August 14) for the Morans, catching and playing center field in the first, and playing center field only in the other two. On August 16, 1892, a Dolan caught for Portland against Salem in the Pacific Northwest League, going 2-for-5 with a double and a stolen base. There is no record indicating that any of these instances are our Tom Dolan. In particular, it is likely that the St. Louis newspapers of the time would have had a note if Tom Dolan had gone to the West Coast to resume playing professional baseball. It seems more likely that these games were played by other players named Dolan.

There are several other errors in the minor league record for Tom Dolan on Baseball-Reference as of January 2021. He is listed as playing for Omaha in the Northwestern League in 1879. The Quad-City Times reported “The Omaha club has engaged a new catcher named Dolan, from Chicago” in June 1879.38 Tom Dolan was with the Utica club at that time. Baseball-Reference also credits Dolan with playing in 1881 for the San Francisco Knickerbockers in the California League. The player with the Knickerbockers was likely Jeff Dolan, who played for that club in 1880. 39

There is no evidence that Tom Dolan went west again in 1881. (It is possible Jeff Dolan was also the player for Omaha in 1879. Playing with Dolan in Omaha was Julius Willigrod, who appears in a box score for the San Francisco Knickerbockers playing against the Chicago club on December 8, 1879, along with a Dolan, catching and playing second base.) Baseball-Reference identifies Tom Dolan as playing for the New York Yorks in the Eastern Championship Association in 1881. The player for the Yorks was an infielder, and Dolan was known primarily as a catcher. Finally, Tom Dolan is credited for playing with Brooklyn in the Interstate Association in 1883, but he spent the entire 1883 season with the Browns.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Bill Lamb and Norman Macht and checked for accuracy by SABR’s fact-cheecking team.

Sources

US Census data was accessed through Geneology.com and Ancestry.com, and other family information was found at Ancestry.com and FindAGrave.com. Stats and records were collected from Baseball-Reference unless otherwise noted. Articles cited in this biography were typically accessed through Newspapers.com and/or Genealogy.com. St. Louis street directories were found through Ancestry.com. Box scores for games involving Dolan from 1873, 1874, 1875, and 1876 were found in various St. Louis papers from the time.

Notes

1 The Dolan family (parents John and Bridget, sons Michael and Thomas) appear in the 1885 New York State Census, with Thomas listed with an age of 1. His age in the 1860 US Census is given as 5, and in subsequent censuses it is given as multiples of 5, except for the 1870 US Census, which gives his age at 18 (born in 1852). His death certificate lists his birth date as January 10, 1859. Given these discrepancies, the most likely year is 1855.

2 “For the Fancy. The Record of the St. Louis Red Stockings,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, November 12, 1876: 7.

3 “Out-Door Sports,” Philadelphia Times, January 17, 1877: 3. The International League is considered baseball’s first minor league.

4 “Baseball,” New York Daily Herald, October 22, 1877: 9.

5 “Local Base-Ball Matters,” The Buffalo Commercial, February 14, 1878: 3.

6 “Our New Men,” Buffalo Sunday Morning News, January 20, 1878: 2.

7 Joseph Overfield, “The First Great Minor League Club,” SABR Baseball Research Journal, 1977.

8 Buffalo Morning Express, October 29, 1878: 4.

9 “Their Records,” Buffalo Morning Express, November 2, 1878: 4.

10 “Pitcher and Catcher,” Buffalo Morning Express, March 6, 1879: 4. It is not clear if the description of Dolan is what Galvin said or what the writer thought.

11 “Sporting Notes,” Buffalo Morning Express, September 30, 1879: 4.

12 “Sporting News,” Chicago Inter Ocean, October 1, 1879: 2. Game accounts are available in multiple papers from October 1, 1879 from Chicago and Buffalo.

13 “Base Ball,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 22, 1879: 3.

14 “Notes,” Buffalo Commercial, April 29, 1881: 3.

15 “Sporting,” Buffalo Commercial, March 10, 1882: 3.

16 “Sporting,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, April 15, 1883: 19.

17 “The New Hand-Ball Court,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, February 11, 1884: 5.

18 Dolan and Deasley had a history. David Nemec referenced an article from the St. Louis Republic that reported that Dolan had a teammate beat up Deasley the previous season so that he would get more playing time (Major League Baseball Profiles, 1871-1900, Volume 1, 2011). The Denver Tribune reported on September 14, 1883 that Dolan and Deasley got into an altercation and that “[Deasley] looked as though a freight train had run over him by the time Dolan had finished” (“St. Louis Club Peculiarities,” pg 7).

19 “A Sensation at the Union Grounds,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, August 24, 1884: 9.

20 “St. Louis Unions, 12; Baltimores, 1,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, September 29, 1884: 7.

21 “The Schedule Meetings,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, March 1, 1885: 9.

22 It seems that the reasons for this varied through the season. At one point Pittsburgh was reported as the holdout, but later Cincinnati was reported to be holding out until Tony Mullane was also reinstated.

23 “Rowe’s Reinstatement,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, September 14, 1885: 8, and “Reinstatement of Gleason and Dolan,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, October 7, 1885: 19.

24 “Release of Sweeney and Dolan,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, June 29, 1886: 8.

25 “Base Ball,” Lincoln Star Journal, May 12, 1887: 4.

26 “Base Ball,” Sioux City Journal, May 12, 1887: 2. The Kansas City Times (“Lincoln, 21 — Denver, 6,” pg. 4) reported a similar description. The Omaha Daily Bee (“Lincoln Defeats Denver,” pgs. 1-2) puts the fines at $25. It should be noted that if Tebeau struck Dolan while tagging him out, it would be impossible for Dolan to have scored three runs in the inning.

27 “Base Ball,” Lincoln Star Journal, May 12, 1887: 4.

28 “Dolan and Tebeau Fight,” The Sporting News, May 14, 1887: 1.

29 “The National Game,” Nebraska State Journal, May 17, 1887: 2.

30 Walks were counted as hits in 1887, which likely explains the high batting average. However, the “power”

Dolan displayed in 1887 was unmatched by anything else in his career. There may have been some quirk of the Lincoln ballpark that contributed to these totals. Five players on the Lincoln club (Dolan, Herr, Shafer, Rowe, and Beckley) all finished the season with double digit numbers in doubles, triples and home runs.

31 “The Act of Dissolution,” Lincoln Evening Call, September 27, 1887: 1.

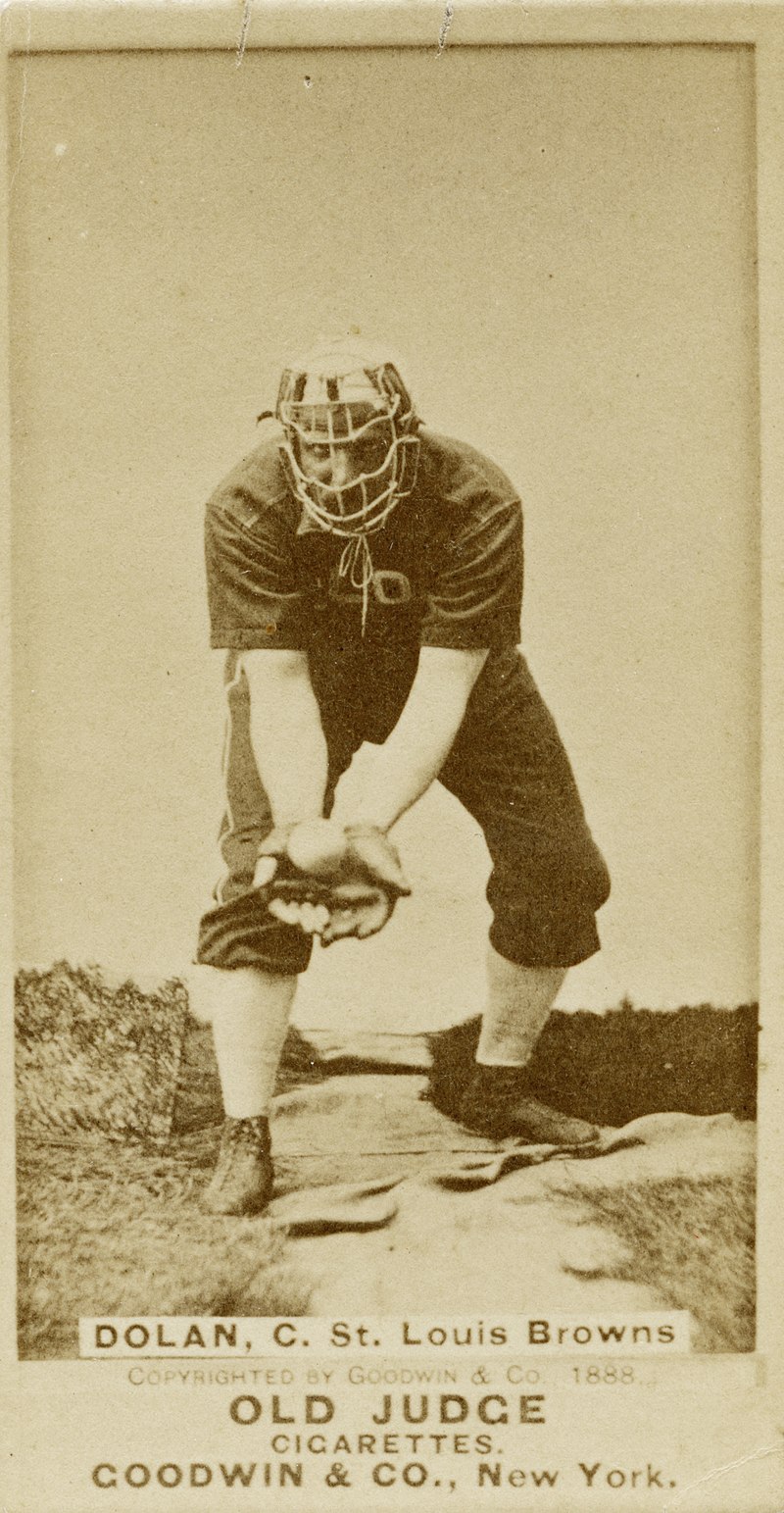

32 The Old Judge baseball cards released in 1887 featured photographs of Dolan in the uniform of the St. Louis Whites, but identified him as being on the St. Louis Browns. This is likely because the photos were taken in early April, when Dolan was practicing and playing with the Whites. Dolan was then taken by the Browns on their spring trip south to Memphis and New Orleans, leading to the speculation that he would be back on the Browns club.

33 Statistics for the 1890 season were published in the Minneapolis Star Tribune (“The Season’s Work,” October 19, 1890: 9). “Status of the Des Moines,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, June 24, 1890: 9.

34 “Diamond Dashes,” St. Paul Globe, March 9, 1890: 6. There is a gravesite for Thomas Dolan, age 2, located in the same plot at Calvary Cemetery as Tom and his wife Tillie. The same note in the St. Paul Globe also mentioned that Dave Rowe’s baby daughter died around that same time.

35 “Mid-Winter Ball Gossip,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, January 20, 1889: 16.

36 “Herr, Sweeney and Weikart Signed,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, July 1, 1890: 8.

37 The incident was extensively covered in Missouri newspapers on April 18 and 19, 1894.

38 “Personal,” Quad-City Times (Davenport, Iowa), June 9, 1879: 1.

39 See for example “Knickerbocker Kalsomine,” San Francisco Chronicle, September 20, 1880: 3, which has J. Dolan catching for the Knickerbockers and T. Dolan catching for the Athletics.

Full Name

Thomas J. Dolan

Born

January 10, 1855 at New York, NY (USA)

Died

January 16, 1913 at St. Louis, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.