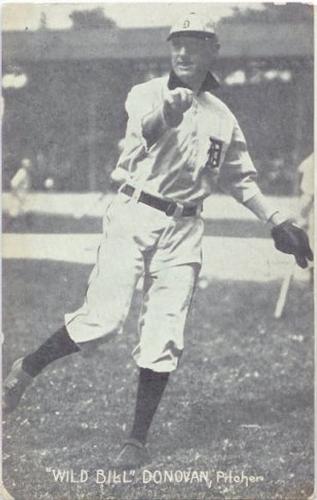

Bill Donovan

A hard-throwing and durable right hander, “Wild Bill” Donovan harnessed his lively curveball, volatile temper and busy social life well enough to become a 25-game winner first in the National League and later in the American. Genial and engaging, Donovan was called “Smiling Bill” by sportswriters and was a fan favorite, though umpires frequently found cause to eject him. Regarded as a “slant ball artist” and a “big game pitcher,” Donovan drew–and often won–key matchups during Detroit’s run of three consecutive World Series appearances from 1907 to 1909. His 25-4 mark in 1907 was the best winning percentage in the AL, and by 1912 he had compiled 184 major league victories, 139 of them in 10 years with the Tigers. “Donovan is a giant and pitches, hits and fields equally well,” Alfred Spink wrote in 1910. “When in good shape Donovan has fine speed, a wonderful break on his fastball and is one of the best fielding pitchers in the country.” After a three year sojourn in the minors, Donovan came back to the big leagues as a player-manager with the floundering New York Yankees, where he enjoyed little success at either vocation. Following his dismissal, he earned a second shot as a big league skipper with the equally futile Phillies. He was ensnared in the Black Sox scandal, discharged again, then personally cleared by new commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis. Donovan resurrected his managerial career in the minors, and appeared to be on the fast track back to the majors when a wreck of America’s most famous train ended his life.

A hard-throwing and durable right hander, “Wild Bill” Donovan harnessed his lively curveball, volatile temper and busy social life well enough to become a 25-game winner first in the National League and later in the American. Genial and engaging, Donovan was called “Smiling Bill” by sportswriters and was a fan favorite, though umpires frequently found cause to eject him. Regarded as a “slant ball artist” and a “big game pitcher,” Donovan drew–and often won–key matchups during Detroit’s run of three consecutive World Series appearances from 1907 to 1909. His 25-4 mark in 1907 was the best winning percentage in the AL, and by 1912 he had compiled 184 major league victories, 139 of them in 10 years with the Tigers. “Donovan is a giant and pitches, hits and fields equally well,” Alfred Spink wrote in 1910. “When in good shape Donovan has fine speed, a wonderful break on his fastball and is one of the best fielding pitchers in the country.” After a three year sojourn in the minors, Donovan came back to the big leagues as a player-manager with the floundering New York Yankees, where he enjoyed little success at either vocation. Following his dismissal, he earned a second shot as a big league skipper with the equally futile Phillies. He was ensnared in the Black Sox scandal, discharged again, then personally cleared by new commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis. Donovan resurrected his managerial career in the minors, and appeared to be on the fast track back to the majors when a wreck of America’s most famous train ended his life.

William Edward Donovan was born October 13, 1876, in Lawrence, Massachusetts, the sixth child of carpenter Jeremiah Donovan and his wife Mary. Young Bill played locally in Lawrence, and later in Waverly, New York. Donovan made his National League debut at age 21 on April 22, 1898 with Washington, where he split time as a pitcher and position player. He was unsuccessful at either. In 39 games as an outfielder, infielder and pitcher, he batted just .165, though he hammered two homers. In 17 games as a hurler, he compiled a 1-6 record, gave up 69 walks in 88 innings, and was dubbed “Wild Bill,” for both his erratic control and his explosive temper.

In 1899, he landed in Brooklyn, which won pennants that year and in 1900. Donovan barely contributed, posting 1-2 records each season. Farmed to Hartford of the Eastern League in 1900, Wild Bill earned another nickname because of his fondness for the city’s popular chowder parties, which featured copious drinking, boisterous singing, impromptu parades and of course, seafood soup. “Chowder Bill” appeared headed for release, but manager Ned Hanlon brought Bill back to Brooklyn. He was rewarded when Donovan developed in 1901, leading the National League with 25 wins against 15 losses, and posting a 2.77 earned run average. He also led or tied for the league lead in games pitched, saves, and walks. He finished 17-15 in 1902.

Ban Johnson and the American League came calling, and Donovan jumped to Detroit just before the two leagues reached a peace treaty. The 5-11, 190-pound curveball artist posted 17-16 and 16-16 marks in his first two seasons in the Motor City. On March 4, 1905, he married Nellie Stephen, of Windsor, Ontario, and the couple lived with extended family on Trumbull Avenue, not far from Bennett Park. Donovan improved to 18-15 in 1905, but suffering from a sore arm in 1906, slumped to 9-15, and led a player revolt to oust manager Bill Armour, a move that angered Johnson.

Under new manager Hughie Jennings, Wild Bill bounced back in a big way. Donovan enjoyed his finest season in 1907, when he posted a 25-4 record with a 2.19 ERA, despite missing the first six weeks of the season because he wasn’t “in shape” to pitch. In The Neyer/James Guide to Pitchers, a Bill James statistical analysis proclaims Donovan’s 1907 campaign the luckiest pitching season in baseball history; according to James, Donovan’s merely passable ERA should have produced a record more like 16-13. In the campaign’s most crucial series, Donovan escaped two bases loaded jams to defeat Philadelphia 5-4 on the last Friday in September, and after two off days, came back Monday to pitch all 17 innings of a tie game, the last 10 brilliantly, to keep Detroit in first place. In the Tigers’ five game loss to the Chicago Cubs in that year’s World Series, Donovan pitched all 12 innings of Game One, which ended in a 3-3 tie, and lost Game Four by a score of 6-1.

Donovan was brilliant again in 1908. He started late again, was suspended twice for umpire-baiting, but still won 18 of 25 decisions, including six by shutout, posted a 2.08 ERA, and issued just 53 walks in 242⅔ innings. He pitched 25 complete games, though he was ejected on five occasions. He was 8-1 against the other three pennant contenders in one of baseball’s greatest races, and he shut out the White Sox on the final day of the season in a winner-take-all match to clinch the AL flag. In the World Series, he lost twice to Chicago’s Orval Overall, who allowed just one run in 18 innings, and the Tigers fell four games to one.

Wild Bill suffered from a sore arm again in 1909, but won eight of 15 decisions, including four by shutout. He was effective down the stretch as the Tigers held off the emerging Philadelphia Athletics by 3½ games and returned to the World Series for the third straight year, this time facing Honus Wagner and the Pittsburgh Pirates. Wild Bill went the distance in a 7-2 Game Two win, but gave up the first two runs in an 8-0 loss in the deciding Game Seven.

Sore arm behind him, Donovan won 17 games in 1910 and 10 in 1911, but he started and won just one game in 1912, and served as a scout for the “Jungaleers.” Midway through the season, Tigers President Frank Navin announced that “Jennings seems to have lost his grip” and that “a change might do the team good,” and hinted that his popular pitcher would be Jennings’s successor at the end of the season (Jennings held the job until 1920). Navin farmed Donovan to Providence of the International League for managerial experience. Wild Bill left Nellie behind, became a part owner of the club the following year and appeared in 17 games as a pitcher in 1913 and 1914. That summer, the franchise was sold to Boston, and Donovan managed young Babe Ruth.

Donovan’s work at Providence was rewarded when he was named manager of New York’s floundering franchise in 1915. The Yankees wanted Jennings, but Navin would not let him go and so they hired his heir apparent. Grantland Rice wrote that Donovan “is unlike any other man in the game with a managerial job…he believes in leading, rather than driving…We believe he is going to play a big part in the new destiny of the Yanks.” Early in the season, Nellie sued Donovan for a divorce, which he did not contest. Wild Bill pitched 33⅔ innings, most on trips to Detroit, and guided the Yankees to a fifth place finish. He continued to draw ejections and suspensions for arguing in 1916, and the Yankees climbed into fourth place. But in 1917, New York–dubbed the “Donovanites”–suffered a series of injuries and slipped to sixth. Ban Johnson orchestrated a transfer of St. Louis Cardinals manager Miller Huggins to New York, which resulted in the unpopular ouster of Smiling Bill. “He was a wonderful fellow and great leader,” Yankee owner Jacob Ruppert said later. “I still think that barring injuries and hard luck Bill Donovan would have brought the Yankees their first pennant. The hardest thing I ever had to do was release him.”

Donovan spent the 1918 season as a coach for Jennings in Detroit, and also pitched in two games, winning one to close out his major league career with a record of 185-139 and an ERA of 2.69. His playing career at an end, Donovan took over the Jersey City team in the International League and led the Skeeters in 1919 and 1920. After two seasons at Jersey City, owner William Baker tabbed Donovan to manage the woeful Philadelphia Phillies in 1921. The team started slowly, and in mid-July, Wild Bill was summoned to Chicago to testify at the Black Sox trial. Baker suggested that because of his familiarity with many of the figures in the case, Donovan “knew too much” about the 1919 World Series fix, and dismissed his manager. But Wild Bill had been a favorite of Kenesaw Mountain Landis when he pitched for Detroit, and the new commissioner, after an investigation, ordered Baker to apologize, and sent Donovan a letter that cleared him completely.

In 1922, New Haven owner George Weiss, later a Hall of Fame executive with the Yankees, hired Donovan on the advice of Ty Cobb, a shareholder in the club, and was rewarded with an Eastern League pennant and a post-season win over IL champion Baltimore. Donovan piloted the New Haven squad again in 1923, but the defending champs were clipped by Hartford and phenom Lou Gehrig.

In December, newspapers speculated that Clark Griffith would name Donovan Washington’s manager during baseball’s winter meetings in Chicago. On Saturday, December 8, Wild Bill and Weiss departed Grand Central Station aboard the Twentieth Century Limited, the New York Central Railroad’s flagship fast train to the Windy City. The train was separated into three sections, each pulled by its own steam locomotive. During the evening, Donovan ate dinner with Baker, NL President John Heydler and Cullen Cain, NL service bureau manager. Smiling Bill denounced the demise of curveball pitching, and invited them back to his compartment for a game of cards, but they declined. Donovan returned alone to his sleeping compartment in the forward part of the second section’s final car, a Pullman observation-sleeper. Weiss, the younger man, had allowed Donovan the lower berth, and was already asleep in the top bunk. At 1:30 on the morning of December 9, in heavy fog and rain, the leading section of the Twentieth Century slammed into an abandoned automobile at a grade crossing at Forsyth, New York, 25 miles east of Erie, Pennsylvania. The second section of the train stopped behind the first to examine the damage and remove the burning automobile, while the lead section resumed its journey. The trailing third section, attempting to catch up, bore down on the second (which had not moved), and the veteran engineer ran through a series of stop signals and smashed into the back of the second section, telescoping and splitting the rear car. Donovan was killed instantly, one of nine people to die, and arguably the most famous person ever killed in an American train wreck. Weiss suffered a serious back injury and a lacerated thigh.

Heydler and others carried word of the 47-year-old Donovan’s demise to the baseball meetings. “The news hits me very hard,” Ruppert said the next day. “It is a great tragedy. I can’t express my sorrow at hearing of Bill’s untimely end. He was still in his prime and one of the greatest managers in baseball. I say this because I know. When he was with the Yankees Donovan had more hard luck that I have ever seen on a ball field. One player after another was injured, but still Donovan kept plugging ahead, and he never forgot how to smile. ‘Smiling Bill’ is what they should have called him.” Donovan was laid to rest in Holy Cross Cemetery in Yeadon, Pennsylvania, near Philadelphia. On Easter Sunday, 1924, a plaque honoring Donovan was placed in the New Haven outfield before an exhibition game to benefit Donovan’s father and sisters. Judge Landis was one of many baseball figures who attended the dedication.

A version of this biography originally appeared in David Jones, ed., “Deadball Stars of the American League” (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, Inc., 2006).

Sources

In researching this article, the author made use of the subject’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, and several contemporary newspapers.

Full Name

William Edward Donovan

Born

October 13, 1876 at Lawrence, MA (USA)

Died

December 9, 1923 at Forsyth, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.