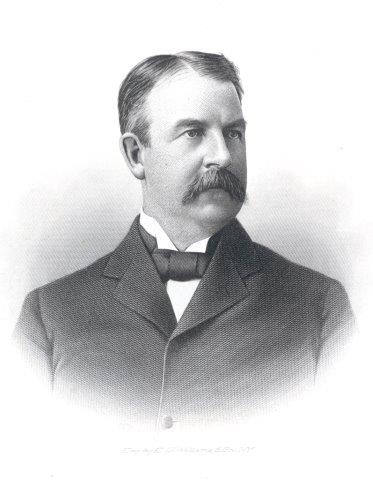

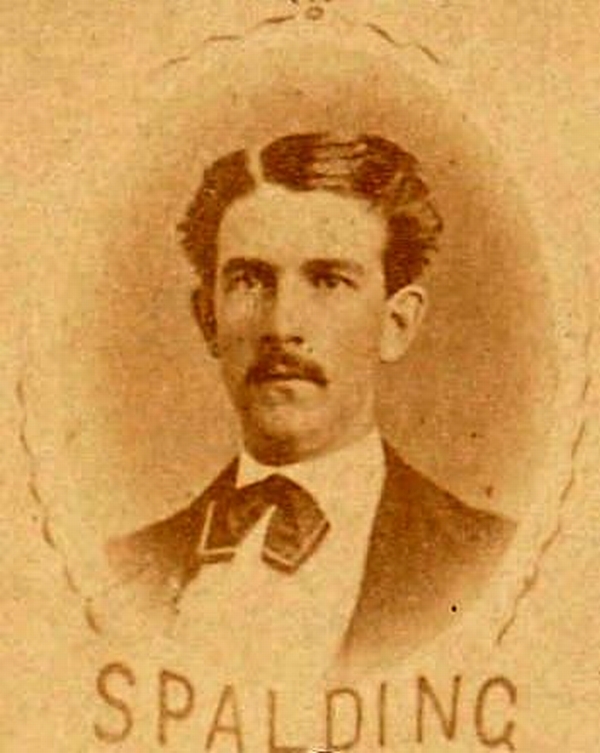

Al Spalding

Albert Spalding’s life story could have been written by Horatio Alger. He had three careers – as a baseball pitcher, a club owner, and a sporting-goods tycoon – and was very successful at all of them. A fourth career, in politics, was just getting under way when he died. And despite an initial setback, ultimately he might well have been successful there, too.

Albert Spalding’s life story could have been written by Horatio Alger. He had three careers – as a baseball pitcher, a club owner, and a sporting-goods tycoon – and was very successful at all of them. A fourth career, in politics, was just getting under way when he died. And despite an initial setback, ultimately he might well have been successful there, too.

The first of three children, Spalding was born on September 2, 1850, in Byron, Illinois, near Rockford, to James and Harriet Spalding. The family was fairly affluent, owning land and horses. However, James Spalding died when Albert was 8 years old, and the family subsequently moved to Rockford. Albert preceded them, living with an aunt, and it is said that he began playing baseball as a defense against loneliness. He became good enough at it to be asked to join the leading amateur team, the Forest Citys.

In 1867 the Chicago Excelsiors sponsored a tournament that featured the Washington Nationals, regarded as the best team in the country. The Nationals routed the Excelsiors, 49-4, but Spalding pitched the Forest Citys to a 29-23 victory over them. He was hired away by the Excelsiors, but soon returned to Rockford, where he worked at various jobs while continuing to pitch. While on tour with Rockford in 1870, Spalding defeated the famous Cincinnati Red Stockings.

Harry Wright, who had managed the Red Stockings, moved to Boston and worked to organize the first professional league, the National Association. He signed players for his own team, the Boston Red Stockings, including Spalding, Ross Barnes, and Fred Cone from Rockford. Wright was an important formative influence on Spalding, imparting organizational skills to the young man.

From the start, Spalding dominated National Association pitching, leading the league in wins for every year of its five-year existence. In 1871 he was 19-10, winning one more than the two second-place pitchers. The following year, Spalding put up a record of 38-8, winning five more than second-place Candy Cummings. He won even more games in 1873 – 41 wins against 14 losses. Increasing his wins total again in 1874, Spalding was 52-16. Remarkably, Spalding appeared in every one of the Red Stockings’ games in 1874. The team played in a total of 71 championship games (excluding exhibitions), and Spalding started 69 of them (65 were complete games), while relieving in the other two. His ERA for the season was 1.92; his career ERA is calculated at 2.13. In 1874 he worked an astounding 617? innings, far more than would ever be assigned to any pitcher in a 162-game season.

In 1874 Wright sent Spalding to England to organize the first foreign tour by American baseball players. The participants were players from the Boston and Athletic (Philadelphia) clubs. They departed July 16, arriving at Liverpool on the 27th. In addition to Liverpool they played games at Manchester, London, Sheffield, and Dublin. There were 14 baseball exhibitions, in which Boston won eight, but also seven cricket matches against top British teams. The Americans astonished the locals by winning six and losing none, the other being drawn because of rain. The victors sailed from England on August 27, returning home September 9.

Spalding had a record of 204-53 in five years, topped by a 54-5 record in 1875, when he had 23 consecutive wins. Not only did he lead in wins for every year of the National Association’s existence, he also increased the number of wins each year over the year before. Overall, he had 91 percent of Boston’s victories in the Association.

After finishing in second place in 1871, the Red Stockings won the next four pennants. Spalding’s performance is described thus by Robert Tiemann: “In the pitcher’s box, Spalding was in complete control, using a fine fastball and change of pace. He was a master at keeping hitters off balance, either by quick-pitching or by holding the ball while the batter fidgeted. In addition, he was a good batsman, adept at opposite field hitting, and a savvy fielder who helped perfect the dropped-popup double play.”1

In addition to his work on the mound, Spalding also played 64 games in the outfield and 52 at first base. He was a very good hitter, too, with a career batting average of .313. In 411 games, he batted in 338 runs.

In addition to his work on the mound, Spalding also played 64 games in the outfield and 52 at first base. He was a very good hitter, too, with a career batting average of .313. In 411 games, he batted in 338 runs.

Because he disapproved of drinking and gambling, Spalding was sympathetic to William Hulbert‘s proposal to organize a new league with stricter discipline. Hence Hulbert was able to lure Spalding, as well as other stars, to his Chicago White Stockings. To prevent the Eastern clubs from retaliating, Hulbert formed the new National League; this meant for Spalding a “promotion” to captain/manager. In the National League’s inaugural year, 1876, Spalding again led the league in which he pitched with 47 wins, but George Bradley of St. Louis, who had a 5-4 record against Spalding, was probably a shade better. Spalding was 47-12, and Chicago won the pennant. In 1877 Spalding abandoned the mound for first base. Bradley was hired to replace him, but the team dropped from first to fifth place. Spalding gave up the captaincy and played in only one game in 1878; he was through as a ballplayer at age 27. It appears that his other interests had taken precedence over ballplaying.

After retiring as a player, Spalding became secretary of the White Stockings, becoming president when Hulbert died in 1882. Spalding believed in strict separation between players and management, with the latter handling financial matters. He built a team that dominated the early 1880s, as the White Stockings won pennants in 1880, 1881, 1882, 1885, and 1886. He was determined to have a clean game that drew respectable citizens to the ballpark. He was innovative, starting the practice of spring training when the team went to Hot Springs, Arkansas, in 1886, and he sponsored a world tour of players in 1888-89.

Cap Anson chronicled this trip as follows: Spalding organized a round-the-world tour with exhibition games between the Chicagos and a picked team, called the All-Americas, from the rest of the league.2 Among the All-America players were John M. Ward, Ned Hanlon, Fred Carroll, and Egyptian Healy. They left Chicago via the Burlington Railroad on October 20, 1888. For about a month they toured the West, playing in such places as Minneapolis/St. Paul, Des Moines, Omaha, Denver, Salt Lake City, and San Francisco. On November 18 the players sailed for Hawaii, arriving a week later. In addition to Honolulu they played in Auckland and a few Australian cities. In January they sailed to Ceylon, where they also played, but they avoided India for health reasons.

On February 7, 1889, the players arrived in Egypt, where they had a game in the shadow of the pyramids. From there they proceeded to Naples, Rome (playing before the king of Italy), Florence, and Paris. In the latter city, on May 8, Ned Williamson tore his kneecap in a game, virtually ending his career. They crossed the Channel that evening, playing in London (before Edward, Prince of Wales) and other British cities, as well as Glasgow, Belfast, and Dublin. In all there were 28 games abroad, the All-Americas winning 14, the Chicagos 11, with three ties. The weary travelers sailed from Queenstown on March 25, arriving in New York on April 6. Two days later there was a game in Brooklyn followed by a banquet at Delmonico’s, at which Chauncey Depew was the speaker, with Mark Twain also in attendance. After further exhibitions at Baltimore, Philadelphia, Boston, Washington, Pittsburgh, Cleveland, and Indianapolis, the touring players arrived back in Chicago on April 19 for a banquet at the Palmer House. The final game was played on the 20th at West Side Park, six months after they had started out.

Meanwhile, Spalding had undergone a career change from player to team owner and sporting-goods magnate. In February 1876 he opened a sporting-goods store, in partnership with his brother Walter, at 118 Randolph Street in Chicago. Within a few years they had a four-story building in Chicago, a five-story store in New York, and outlets across the country from Oregon to Rhode Island. Spalding was able to use his influence to supply balls, bats, uniforms, and other equipment to the league. He published semiofficial guides and instruction manuals, carrying this practice over to other sports to promote his merchandise.

Spalding became the National League’s most influential owner, promoting the reserve clause and its system of “indentured serfdom,” i.e., keeping salaries down and controlling where men could play. He assumed a moral authority over the players, railing against drinking in the pages of his Guide.3 He set up what many consider the second “World Series,” against the Association’s St. Louis Browns, but Chicago only achieved a tie in 1885 and then lost four of six the following year.4 This induced Spalding to break up his team. First to go were the drinkers. Mike Kelly was sold to Boston for $10,000, and Jim McCormick and George Gore were axed. The following year star pitcher John Clarkson brought another $10,000 from Boston. Thus ended the Chicago dynasty.

By 1890 the players had a union, the Brotherhood, and rebelled, forming a rival league. Spalding led the effort to undermine the Players Association and ultimately turned Organized Baseball into a monopolistic trust. But he began to tire of baseball and turned over the presidency of the Chicago team to James Hart in 1892. According to Francis Richter, who regarded Spalding as “the greatest man the National game has produced,” Spalding put the game above selfish interests.5 This caused him to come out of retirement to oppose the syndicate scheme of Andrew Freedman and John T. Brush. He ran for the league presidency against old friend Nicholas Young and actually “won” through a flawed process that was challenged in the courts. When it appeared that he would ultimately lose, he resigned the NL presidency in April 1902.

Spalding then sold out completely and retired to Point Loma, California. He devoted himself to proving baseball a uniquely American game, promoting the myth of its invention by Abner Doubleday.

Spalding then sold out completely and retired to Point Loma, California. He devoted himself to proving baseball a uniquely American game, promoting the myth of its invention by Abner Doubleday.

From a baseball standpoint Spalding’s most significant relationship was that with Adrian “Cap” Anson. They had started out with Rockford, came to Chicago in 1876, and worked to build up the White Stockings. Anson shared Spalding’s views and enforced his values on the field. However, Anson and James Hart had differences dating back to the world tour, and when Hart took over the team the friction escalated until Anson was dismissed after the 1897 season. On the one hand, it was time for a change. On the other, Anson felt stabbed in the back by his old friend. Spalding tried to placate Anson with a testimonial said to be worth $50,000 (over $1 million today), but Anson was too proud to accept. In Anson’s autobiography the envy is clear: They started out together; Spalding prospered, while all of Anson’s investments turned sour.6

Spalding was married twice, first to Josie Keith in 1875; they had a son Keith. Josie died in 1899, and in 1901 Spalding married the widow Elizabeth Mayer Churchill. They had been clandestine lovers for some time and had a son (Spalding Brown Spalding, later changed to Albert Goodwill Jr.) out of wedlock. After marrying Elizabeth, Spalding acknowledged the paternity and also adopted her other son, Durand Churchill. He also took an interest in the career of his nephew Albert Spalding (1889-1953), a world-class violinist. Elizabeth was devoted to theosophy, and the Spaldings moved to Point Loma to be part of the community founded by Katherine Tingley.

Spalding had been in the second echelon of Chicago society, but in the San Diego area he was a civic leader. This led to his campaign for the Senate in 1910. Although he was the popular choice, the insiders in the state legislature chose his opponent, John D. Works. Spalding died of a stroke on September 9, 1915, leaving an estate of $600,000 to his wife and three sons. Twenty-five years later, in 1939, he was named to the National Baseball Hall of Fame by the Old Timers Committee.

This biography is included in “Boston’s First Nine: The 1871-75 Boston Red Stockings” (SABR, 2016), edited by Bob LeMoine and Bill Nowlin.

Sources

In addition to the sources in the notes, the author also consulted:

Chicago Tribune, September 10, 1915: 1; September 15, 1915: 13.

Gold, Eddie, and Art Ahrens. The Golden Era Cubs, 1876-1940 (Chicago: Bonus Books, 1985).

Golenbock, Peter. Wrigleyville, a Magical History Tour of the Chicago Cubs (New York: St. Martin’s, 1996).

Levine, Peter. A.G. Spalding and the Rise of Baseball, the Promise of American Sport (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985).

Nemec, David. The Great Encyclopedia of 19th-Century Major League Baseball (New York: Donald Fine Books, 1997).

Nineteenth Century Notes. Newsletter of the Nineteenth Century Committee, Society for American Baseball Research, No. 99 (1999): 2, 2.

Smith, Duane A. “Spalding, Albert Goodwill ‘Al.’ ” Biographical Dictionary of American Sports: Baseball. Revised and expanded edition (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood, 2000).

Spalding, Albert G. America’s National Game (New York: American Sports, 1911).

Spalding’s Official Base Ball Guide. Various editions. (Chicago and New York: A.G. Spalding & Bros.)

Notes

1 Quoted in William E. McMahon, “Albert Goodwill Spalding,” in Frederick Ivor-Campbell, Robert L. Tiemann, and Mark Rucker, eds., Baseball’s First Stars (Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 1996), 154.

2 Adrian C. Anson, A Ball Player’s Career, Being the Personal Experiences and Reminiscences of Adrian Anson (Chicago: Era Pub. Co., 1900), 140-285.

3 Spalding’s Official Base Ball Guide (1886), 14-16.

4 The first world’s series is now often considered to be the 1884 one between Providence and New York.

5 Francis C. Richter, “Heroic Figure Passes From the Stage,” Sporting Life, September 18, 1915: 3, 7.

6 Anson, 306-314.

Full Name

Albert Goodwill Spalding

Born

September 2, 1850 at Byron, IL (USA)

Died

September 9, 1915 at San Diego, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.