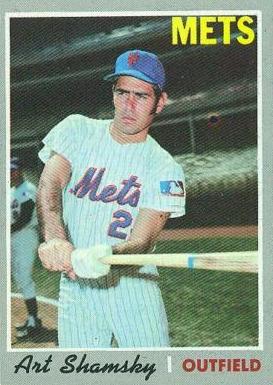

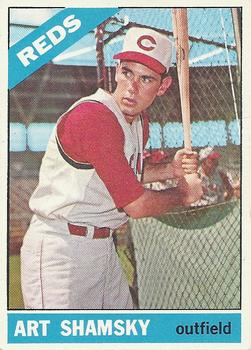

Art Shamsky

In the locker room celebration after the New York Mets won the 1969 National League pennant, he was quoted by the New York Daily News as saying, “I’ll walk down the street in New York now and people will say, ‘There’s Art Shamsky of the Mets.’ People used to laugh. They won’t anymore.’”1 Indeed, after his performance in the 1969 National League Championship Series, a three-game sweep of the Atlanta Braves, nobody would laugh. His seven hits in the NLCS led both teams and, had the honor been bestowed, Shamsky might well have been named Most Valuable Player. He hit .300 during that Miracle Mets season and became a fan favorite, particularly among the area’s large Jewish population.

Art Shamsky played professional baseball for 13 seasons, between 1960 and 1972, eight in the major leagues. Nicknamed Sham and Smasher, the lanky left-handed outfielder/first baseman began his career with the Cincinnati Reds organization and later became a key part of the 1969 world champion Mets offense. In addition to his contributions to the Mets, Shamsky is perhaps best known for his four consecutive home runs in August 1966 while he was with Cincinnati. He is one of 17 players to hit four straight homers over a span of two games and the only major leaguer to hit three home runs in a game without being in the starting lineup.

Arthur Louis Shamsky was born in St. Louis on October 14, 1941. He grew up in a predominantly middle-class Jewish area of University City, son of William and Sadie Shamsky. William’s family came from the Ukraine while Sadie’s family originated from Poland. His father ran a scrap-iron business. Art, the only son, had an older sister, Delores. “We were Jewish but we weren’t very religious,” he told an interviewer. “We observed the holidays but we didn’t make a big thing out of religion. About all I did as a player in recognizing the religion was to take off the major Jewish holidays.”2

“As a young boy growing up, my life was basically two things, following the St. Louis Cardinals or playing baseball with my friends,” Shamsky said.3 He told another interviewer, “We used to put a quarter in the light machine at tennis courts just to hit some fungoes at night. We played every day, we played in the rain, we played every chance we got.”4 He listened to Harry Caray call Cardinals games on the radio and his biggest hero was Stan Musial.

Shamsky was an outstanding basketball and baseball player at University City High. Famous alumni of the school include playwright Tennessee Williams, southpaw Ken Holtzman (who is the winningest Jewish pitcher in the major leagues and was a teammate of Shamsky’s on the 1972 Oakland A’s), and one-time Mets outfielder Bernard Gilkey. Shamsky didn’t try out for baseball until his senior year in high school. He played two games at Busch Stadium during the state high-school playoffs, getting hits in both, but University City lost in the championship game.

“I wasn’t spectacular,” Shamsky said. “I hit only about .300, and I didn’t consider pro ball right away. I was only 16 when I graduated from high school.”5 After graduating in 1958, Shamsky attended the University of Missouri for a year and played baseball. He then decided to leave school to play professionally.

Shamsky got offers from many teams, and signed with the Cincinnati Reds on September 9, 1959. “My father would have preferred that I had gone into business, but he was into baseball and I think he was thrilled when I signed,” Shamsky has said. “My mother certainly wanted me to go to college and become a doctor, of course. What else is a Jewish boy supposed to do?”6 (Shamsky’s sister became a lawyer.)

Shamsky hit a home run in his first professional at-bat, for the Geneva Redlegs in the New York-Penn League. He was a teammate of Tony Perez and Pete Rose (whom he roomed with while with Geneva). For the season, playing in 119 games, Shamsky hit .271, with 18 home runs and 86 RBIs, making the league all-star team. He led the league’s outfielders in assists, with 24. Despite the presence of the two baseball superstar teammates, Shamsky said, “That Class D team was so bad that we got our manager fired with a third of the season left.”7 In a move Shamsky considered somewhat ironic, he was promoted to Class-B Topeka while his teammates Rose and Perez remained in Class D. In a piece he wrote for the New York Times in 1986, Shamsky said in jest, “I guess, though, when you stop to think about it, somebody knew something because they’re still playing and making a lot of money and I’m watching.”8

Shamsky hit .288 with 15 home runs and 66 RBIs in 116 games for the Topeka Reds of the Three-I League in 1961. Dave Bristol, who managed him in the minor leagues in 1961 and 1962 and later with the Reds, remembered the left-handed hitter’s power. “It’s Artie’s wrists,” said Bristol. “Watch Artie’s wrists when he whips a bat and you won’t be surprised by the long balls he hits. … They had a big barn behind the fence in right-center at Topeka. Artie’s the only player I ever saw bounce a homer off the roof of that barn.”9

Shamsky’s 1962 season was spent with the Macon Peaches in the Class-A Sally League. He started out strong, hitting six homers in the first 13 games, but went on the shelf for seven weeks with a hand injury. He ended up on the disabled list when he had surgery to remove calluses from his left hand. In 81 games, he hit .284 with 16 home runs and 61 RBIs. Shamsky was promoted to the Reds’ Triple-A affiliate San Diego Padres, where he spent two seasons in the Pacific Coast League. In 1963 he played in 150 games, batting .267 with 18 home runs and 68 RBIs. In 1964 the Padres, including Shamsky and teammates Tommy Helms, Don Pavletich, Tony Perez, and other future major leaguers, won the PCL championship. Shamsky hit .272, slammed 25 home runs, and drove in 69, setting the record for the longest home run hit in the Padres’ park, a tape-measure shot of 500 feet.10

Shamsky was now ready for the major leagues. “Art Shamsky has great potential,” said San Diego general manager Eddie Leishman, who was named Minor League Executive of the Year after Shamsky and Co. took the ’64 league title. “He certainly has the tools to make the grade and go far in baseball. He has the swing and actions of the Yankees’ Joe Pepitone.”11

Shamsky made his major-league debut on April 17, 1965, against the very team he loved growing up as a child, the St. Louis Cardinals. In front of family and friends at Busch Stadium, he batted for pitcher Gerry Arrigo in the seventh inning of a game the Cardinals won, 8-0. Shamsky had no easy task for a debut, as he was called upon to hit against one of the greatest pitchers of all time. “I had to pinch-hit against Bob Gibson, a great pitcher, and I was really nervous. I ended up striking out and I was very upset. However, I got over it, and the next time I faced him I pinch-hit a home run.”12

Shamsky’s first hit came five days later, at Wrigley Field against the Chicago Cubs, when he lined a pinch-hit single to right in the ninth inning off Ted Abernathy. His first major-league home run was launched in the first game of a doubleheader against the Mets on May 2. It was a pinch-hit two-run blast off Mets reliever Tom Parsons in the bottom of the fifth inning. The batter he hit for was the great Frank Robinson, who was in his final season with the Reds.

It was also during his rookie season that Shamsky got to face fellow University City High alumnus Ken Holtzman, four years his junior and also a rookie in the big leagues. Shamsky walked and sacrificed in his only two career plate appearances against the Cubs southpaw, an example of the strict platooning that Shamsky endured during his career. (He hit .223 with three home runs in 112 career at-bats against lefties and .255 with 65 homers in 1,574 at-bats against righties.)

Shamsky did not end up as a regular outfielder in 1965, but instead became the top pinch-hitter on a team boasting a lineup of All-Stars and future Hall of Famers. Pete Rose played in all 162 games and was the National League’s starting second baseman in the All-Star Game; Frank Robinson belted 33 home runs, and Tony Perez hit .260 in his rookie year. Cincinnati had two 20-game winners, Sammy Ellis and Jim Maloney. The 1965 Reds finished in fourth place at 89-73, eight games behind the Los Angeles Dodgers.

After playing for Santurce in the Puerto Rican Winter League in the winter of ’65, Shamsky returned to Cincinnati the following spring. He appeared in 96 games for the Reds, again serving primarily as a pinch-hitter and reserve outfielder. His team finished in seventh place in the National League with a record of 76-84, falling to 18 games behind the Dodgers.

During the 1966 season, Shamsky made history on August 12 and 14. Over the span of two games at Crosley Field in Cincinnati, he homered in four consecutive at-bats. On the 12th, the Reds and the Pittsburgh Pirates played an extra-inning affair in which 11 home runs were hit. The Pirates were ahead six times and the Reds three. With the Pirates ahead 7-6 in the eighth inning, Shamsky came into the game to play left field.

During the 1966 season, Shamsky made history on August 12 and 14. Over the span of two games at Crosley Field in Cincinnati, he homered in four consecutive at-bats. On the 12th, the Reds and the Pittsburgh Pirates played an extra-inning affair in which 11 home runs were hit. The Pirates were ahead six times and the Reds three. With the Pirates ahead 7-6 in the eighth inning, Shamsky came into the game to play left field.

In the bottom of the inning, with a runner on base, Shamsky homered off Al McBean to give Cincinnati an 8-7 lead. The Pirates tied the game in the ninth and took the lead in the 10th on a Willie Stargell home run. In the bottom of the frame, facing pitcher Roy Face, Shamsky hit another shot into the right-field seats to tie the game again. Finally, in the home 11th, with Pittsburgh up 11-9, Shamsky faced pitcher Billy O’Dell. On a 3-and-1 count, he homered a third time, another two-run blast to tie the game at 11-11. Teammate Pete Rose called it “one of the greatest clutch-hitting exhibitions ever seen.”13

In the end, however, despite Shamsky’s heroics, the Pirates came away with a 14-11 victory in 13 innings. After the game, he took the loss hard and declined an opportunity to go on a Cincinnati postgame radio show, Star of the Game. “How can you be a star when your team loses?” he commented.14

Despite Shamsky’s becoming the first player to homer three times after not starting, Cincinnati manager Dave Bristol sat him out for the second game of the series, against Pittsburgh lefty Woodie Fryman. The Reds won that game, 11-0, a contest that was called during the sixth inning after a 50-minute rain delay. He then sat out the start of the rubber game of the series on the 14th, against right-hander Vernon Law. When Bristol sent Shamsky up to bat for catcher Johnny Edwards in the seventh, he connected for a two-run shot against Law that gave the Reds a brief 2-1 advantage. After the game, a 4-2 loss to the Bucs, the wild speculation and media circus began. Could he do it again? Could he make it five in a row?

Shamsky said he wasn’t even aware he had tied a major-league record. “I didn’t know a thing about it until the Cincinnati public address announcer made mention of it after my fourth homer. I can’t say I tried to hit any of them. … It’s a funny thing. They come pretty easy when I don’t try.”15

Shamsky’s teammates made light of the event. “Just think,” kidded Sammy Ellis, “a few days ago Artie was just an average bench warmer. Today he’s a national hero.” Outfielder Tommy Harper said, “Artie’s act sure is a tough one to follow. I struck out after three (actually, two) of those four homers. No one noticed it, though, they were still cheering Artie.” Shamsky himself said, “If I do hit the fifth straight one, there will be champagne for everyone — on me.”16

After the Pirates series, the Reds moved on to Los Angeles to play the Dodgers. Shamsky sat against Dodgers lefty Claude Osteen on the night of August 15, but in the eighth inning he stepped up to the plate to bat for Tony Perez against righty reliever Bob Miller with no outs and nobody on base, and lined a single to right field. “If I was going to hit one out of the park that would have been the pitch,” he said.17 Sportswriter Jack Disney wrote the next day, “By lining a base hit to right in the eighth inning at Dodger Stadium, the Cincinnati outfielder was stopped three bases short of immortality.” The Los Angeles Herald-Examiner ran a parody of “Casey at the Bat” that concluded, “But there is no joy in any town — just tears and sadness mingled; After four straight homers, mighty Shamsky only singled.18

Shamsky’s four consecutive home runs put him in impressive company. Other players to hit four home runs in four straight plate appearances over multiple games include Albert Pujols, Troy Glaus, Shawn Green, Manny Ramirez, Bo Jackson, Larry Herndon, Deron Johnson, Mike Epstein, Bobby Murcer, Johnny Blanchard, Jimmie Foxx, Mickey Mantle, Hank Greenberg, Ralph Kiner, and Shamsky’s hero Stan Musial. That season Shamsky hit 21 home runs in just 234 at-bats, finishing second on the team behind Deron Johnson’s 24 in more than 500 at-bats. Despite his .521 slugging percentage, Shamsky finished the season batting only .231 with just 47 RBIs.

The next season, 1967, was Shamsky’s last with the Reds. He had had an injury-riddled year, struggling primarily with back issues that would plague his entire career. He hit only .197 with just 13 RBIs and hit only three home runs all season. Shamsky was traded to the Mets on November 8 for utility infielder Bob Johnson.

Initially, Shamsky was not happy about the trade. He learned the news while recovering from surgery in St. Louis to have a cyst removed from his tailbone. Reds general manager Bob Howsam called him at home, and Art expected to be asked how he was feeling. He immediately said he felt great and was looking forward to next season. “That’s good,” said Howsam, “because we just traded you to the Mets.”19

Shamsky was leaving an organization and teammates he had been with his entire career for the team with the worst record in baseball in five of its six years of existence. After Howsam called, Mets GM Bing Devine phoned to reassure Shamsky about coming to New York. Devine was previously general manager of the Cardinals and had known Shamsky growing up. Things were different, he told Art, and the fans were great. “Two days later I picked up the St. Louis newspaper and read that Bing Devine was just named general manager of the Cardinals. … Two days earlier he had told me how good the Met organization was and how great New York City was, and now he left to come back home. It was the longest winter of my life.”20

Still, in 1968 things were looking brighter for both Shamsky and the Mets. Three weeks after Shamsky was traded to New York, the Mets acquired manager Gil Hodges in a trade with Washington. Johnny Murphy, who helped negotiate the Hodges deal, succeeded Bing Devine as general manager and brought up young talent from the minors that — combined with Hodges at the helm — brought a winning atmosphere to a team that had known only misery in its brief existence. Upon arriving in New York, Art joked that, like Sandy Koufax in 1965, he would miss any World Series game that fell on a major Jewish holiday. Everybody laughed; no one could have predicted the miracle to come one year later.

The 1968 New York Mets were the one of the youngest teams in the major leagues, with an average age of 25.9. (Only the Astros had younger hitters, 25.6, and only the Cubs had younger pitchers, 25.4.) The Mets had a core of returning position players in shortstop Bud Harrelson, first baseman Ed Kranepool, catcher Jerry Grote, and outfielders Ron Swoboda and Cleon Jones. The team also now had young players like Tommie Agee and Al Weis, both brought over in a trade with the Chicago White Sox, and Ken Boswell made the club for the first time out of spring training. Boswell, like Shamsky part of a left-handed platoon, became Art’s close friend and roommate.

It was pitching, however, that would carry the team to a world championship. Flamethrower Nolan Ryan won the job as a starter in spring training, and rookie Jerry Koosman, arguably the greatest southpaw in Mets history, made the team despite a mediocre September call-up in 1967. Koosman finished second in Rookie of the Year voting to the Reds’ Johnny Bench in 1968. Then, of course, there was Tom Seaver, who himself had won the Rookie of the Year award the previous season. Though the Mets barely avoided the basement in the final season with a 10-team National League, the 1968 Mets had a different look and feel than their predecessors.

Even with a mediocre .238 average, Shamsky hit 12 home runs with 48 RBIs. “While we weren’t breaking any records in 1968, we were competitive,” Shamsky said. “We were a little less than a .500 ballclub through the middle of the season. The one thing we did have, though, was harmony. It was a clubhouse filled with people who generally liked each other. We had a few ‘characters’ and some loners, but, all in all, the 1968 Mets were a team that pulled for each other.”21

Shamsky, a bachelor, also spent his first offseason in New York. “The city had put its claws on me. I learned that New York City is really one of a kind. … The city energizes you. There is never a dull moment in New York City. After a few months I fell in love with the city. And I got used to ‘Auttie.’ It’s Artie in New York City lingo. I was okay with it now.”22

The next season, 1969, was the first year of divisional play and new National League teams were added in Montreal and San Diego. Gil Hodges, who had suffered a heart attack right before the end of the 1968 season, predicted that the Mets would win 85 games. His club won 100.

Yet the season could not have started any worse for Shamsky. After he had played in only three spring-training games, his back went out. “I was about to play first base that afternoon (March 15, 1969), and we were taking batting practice on the other field. When we finished our swings, I said to Kenny [Boswell], c’mon down in the right-field corner and throw me some grounders. He did, and about the 15th one, I bent over and felt something snap in my back. It was like somebody had taken a gun and shot me. I felt this pain shoot all the way down my left leg.”23 After what was initially thought to be back spasms, Shamsky was diagnosed with a slipped disk, which was pressing against the sciatic nerve. Doctors told him to get plenty of bed rest, take pain medications, and even wear a protective corset. He was unable to get out of bed for a week. One doctor even told him he might never play again. His condition began to improve, however, and he soon felt strong enough to pick up a bat.

After three weeks Shamsky was given permission by the medical staff to work out, but he played the entire 1969 season in pain, even taking pain medications throughout the playoffs and World Series.24 Just before the Mets were to leave St. Petersburg and head north in April, Shamsky was informed by Hodges and GM Johnny Murphy that he was going on the disabled list. After three weeks on the DL, rehab games at Triple-A Tidewater would follow.

Shamsky did not take the news well. The last thing he wanted was to get sent down by a ninth-place team. He even considered retirement. He didn’t know if he would ever be recalled to the Mets and was given no guarantees by Hodges. He was placed on the disabled list on April 8 and came off on April 29. He was optioned to Tidewater and flew to Syracuse for a game against the Chiefs. In his first game he got three hits, including a grand slam, to highlight a 10-run first inning in a 13-2 Tidewater victory. Mets farm director Whitey Herzog saw him hit the grand slam and said, “What the hell are you doing here?”25

After batting .289 with five doubles, four homers, and 12 RBIs in 11 games with the Tides, Shamsky was recalled by the Mets on May 13. In his first game back, he hit a pinch-hit RBI single against the Atlanta Braves at Shea. From his time rehabbing, he had learned how to become a better hitter, using a heavier bat and hitting to all fields. He adjusted his swing to make better contact and cut down on his strikeouts. In 1969 he struck out only 32 times in 302 at-bats

With the Mets Shamsky became part of a crowded outfield with Ron Swoboda, Tommie Agee, Cleon Jones, and Rod Gaspar, who’d come north with the club after Shamsky went down. Gil Hodges liked to platoon his players, using as many of them as possible. For the left-right combo in right field, Shamsky shared time with Swoboda, and he made the most of it. He began swinging the bat with power and was hitting nearly .350 in August.

Shamsky got the game-winning RBI five times that season. None came bigger than on June 6. He lined an eighth-inning pinch-hit single off pitcher Gary Ross to break a 3-3 tie in San Diego. The Mets won, 5-3, a franchise-record eighth in a row. They wound up winning 11 in a row. After trailing the Chicago Cubs by 9½ games on August 13, New York took over first place for good on September 10 and clinched the National League East title on September 24. Shamsky played in 100 games and for only time in his professional career, he hit .300 — exactly that figure — to place second on the team to Cleon Jones’s .340. He was also second on the team in home runs with 14, behind Tommie Agee’s 26.

Shamsky indeed sat out Rosh Hashanah with the Mets battling for first place late in the season. In typically miraculous fashion of the final push that month, the Mets won both ends of a September 12 doubleheader by identical 1-0 scores with the pitchers driving in the only run in each game. The Mets won again the next day with Shamsky still sitting it out in the hotel. Back on the field on Sunday and batting cleanup … the Mets lost. In 11 games after sitting out the Jewish holiday, Shamsky batted .306 with a homer and six RBIs — with the Mets losing just three times with him in the lineup (and one of those defeats came after the Mets had clinched the division).

In the National League Championship Series, against the Atlanta Braves, Hodges continued his platoon system and Shamsky was in the starting lineup to face right-handed pitching — batting cleanup — for all three games of the best-of-five series. He went 7-for-13 at the plate (.538), but had only one RBI.

After the three-game sweep of Atlanta, the Mets faced the heavily favored Baltimore Orioles in the World Series, winner of 109 regular-season games. With left-handers Mike Cuellar and Dave McNally making four appearances for the Orioles, Shamsky sat for four of the five games. In Game Three, against right-hander Jim Palmer, he started and batted fourth. He entered Game One as a pinch-hitter with two outs in the ninth inning. The Mets trailed 4-1 and had runners on first and second. “I would be lying if I didn’t say my heart was beating as fast as it could,” he said. “Even though I had hit over .500 in the playoffs and was swinging the bat well, I was nervous.”26 Shamsky grounded out to second baseman Davey Johnson to end the game. The Mets won the next four games to win the Series, but Shamsky had no hits in six at-bats.

While the 1970 Mets were unable to repeat as NL East champs, Shamsky was almost as solid as in 1969. Splitting time between first base and right field, he led the team in hitting with a .293 batting average, with 11 home runs and 49 runs batted in. His RBIs and 122 games played were career highs as a major leaguer. But 1971 was another injury-plagued season, as he lost his platoon positions at first base and right field to left-handed hitters Dave Marshall and Ed Kranepool. Playing in 68 games, Shamsky hit only .185 with five home runs and 18 RBIs. On October 18, 1971, the Mets traded Shamsky along with three minor-league pitchers to the Cardinals for four players, including Harry Parker and Jim Beauchamp.

Shamsky did not survive spring training, however, and was unconditionally released by the Cardinals on April 9, 1972. He signed as a free agent with the Cubs but played in only 15 games, hitting .125 with no home runs and one RBI. The Oakland A’s purchased his contract in June but released him on July 18 after he had appeared in eight games with no hits in seven at-bats. “This time I decided to quit,” he told an interviewer. “Three teams didn’t want me. That was enough.”27

While still with the Mets, Shamsky had opened restaurants with former Yankee and Met Phil Linz, and later became a real-estate consultant. He was a play-by-play and color broadcaster for the Mets in 1980 and 1981. In 1980 he worked alongside Bob Goldsholl for cable, and in ’81, he did radio and cable TV with Ralph Kiner, Bob Murphy, and Steve Albert. In a 1999 episode of the sitcom Everybody Loves Raymond, Shamsky appeared as himself along other 1969 teammates. (The dog on the show was named Shamsky and others, including comedian Jon Stewart, have followed suit in their pet naming.) In 2004 Shamsky wrote a book with Barry Zeman called The Magnificent Seasons. It is the story of the three championship sports teams in New York in 1969 and 1970, the Mets, Jets, and Knicks.

In 2007 it was announced that Shamsky, Ken Holtzman, and Ron Blomberg would manage in the new Israel Baseball League. “I decided to get involved in the new Israeli Baseball League because I like the challenge of starting something at the very beginning … particularly in a country that is just beginning to develop the game of baseball,” Shamsky was quoted as saying in Mets Inside Pitch. “Managing is something I thought I would never be interested in, but this situation is different. There are many transplanted New Yorkers in Israel, and many New York Mets fans. I’m hoping that my credibility will help the new league get off on the right track.”28 Shamsky’s team, the Modi’in Miracle, finished in third place in the six-team league, at 22-19. Although the league halted operations after one season, Shamsky continued to be active in the Israel Association for Baseball, making frequent visits to Israel to promote hardball in the Holy Land.

As the 50th Anniversary of the ’69 Mets season approached, Shamsky authored another book (this time with baseball writer Erik Sherman), entitled, After The Miracle (2019). With his chronicling of the team and frequent attendance at alumni events, he has become an unofficial ambassador of the 1969 New York Mets.

After The Miracle addresses the 1969 Mets season in the context of the politics of the day, including both the Apollo 11 Moon landing, and the war in Vietnam. More importantly, as the title of the book implies, the focus is also on the lives of his teammates 50 years on.

Shamsky has been given a gift many of his former teammates have sadly not been given. Health. As of March 2019, Tom Seaver’s family announced that he had dementia and would completely retire from public life, ’62 and ’69 Met Ed Kranepool had long been awaiting a kidney transplant, and Shamsky’s good friend Bud Harrelson is fighting back against the onset of Alzheimer’s.

“Days are long, years are short,’’ pitcher Jerry Koosman, told New York Newsday. “I still mourn for the ones we lost. When you lose a person, you lose part of your team. In our age group, we’re not getting healthier. We’re coming to the end of our rope.”29

A central part of Shamsky’s book is a May 2017 reunion visit to Seaver’s 116-acre vineyard in Calistoga, California. He and Sherman, along with Harrelson, Jerry Koosman, and Ron Swoboda made the trip.

“We knew Tom Seaver wasn’t traveling to this area anymore (New York), so we decided to take a trip out there,” said Shamsky. “Even that was difficult because we had to coordinate three other guys to go. Once we got there, we didn’t even know if Tom would feel well enough to see us…We were able to sit down and reminisce and spend time with Tom at his house and go out to lunch. We talked about how important that season was to us and how important we were to each other.”30

“We knew we would never all be together like this again…,”says Shamsky. “It was the lengthiest of goodbyes. Nobody wanted to leave.”31

For his eight-year major-league career, Shamsky hit .253 with 68 home runs and 233 RBIs. He married twice and had two daughters and, as of 2013, five grandchildren. He still resides in the New York area. Shamsky is a member of the New York Jewish Sports Hall of Fame and was inducted into the National Jewish Sports Hall of Fame in 1994. The bat he used to swat four straight homers is on display at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Shamsky has expressed pride in what the 1969 Mets accomplished. “History will show that a team that was a 100-to-1 long shot at the beginning of the season became the toast of the sports world seven months later,” he said “I have always said that the 1969 New York Mets probably weren’t the greatest baseball team to win the World Series, but they were certainly one of the most memorable.”32

Art Shamsky attended the Weekend celebration of the ’69 Mets in June 2019 at Citi Field.

Last revised: June 30, 2019

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted:

Ruttman, Larry. American Jews and America’s Game: Voices of a Growing Legacy in Baseball (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2013.

“Shamsky Bat to Fame Hall,” Cincinnati Post and Times-Star, August 16, 1966.

Art Shamsky clip file, National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Notes

1 Art Shamsky with Barry Zeman, The Magnificent Seasons (New York: Thomas Dunne Books, 2004), 142.

2 Maury Allen, After the Miracle: The 1969 Mets Twenty Years Later (New York: Franklin Watts, 1989), 198.

3 Shamsky and Zeman, 255.

4 Allen, 199.

5 “Art Shamsky’s Long Drive for Majors May Be Over,” St. Louis Post Dispatch, April 16, 1965.

6 Allen, 199.

7 Art Shamsky, “Rose and Perez Can Do It, So Why Not Me Too?” New York Times. April 6, 1986.

8 Shamsky, “Rose and Perez Can Do It, So Why Not Me Too?”

9 Earl Lawson, “Shamsky Looks Like Comedian — N.L. Pitchers Wish He Were,” Cincinnati Post, May 28, 1966.

10 Lawson, “Shamsky Looks Like Comedian — N.L. Pitchers Wish He Were.”

11 “Art Shamsky’s Long Drive.”

12 Clipping in Shamsky’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame. The quote is not quite accurate. Shamsky did hit a pinch-hit home run off Gibson on June 8, but not the next time the two faced each other, on April 23. In that game he got a pinch-hit single off Gibson.

13 Earl Lawson, “Shamsky Equals Record, Hitting 4 HRs In Row,” Cincinnati Post, August 27, 1966.

14 Si Burick, “Shamsky Lets His Stick Do the Swaggering,” Dayton Daily News, August 15, 1966.

15 Jack Disney, “End of Shamsky Era,” Los Angeles Herald Examiner, August 16, 1966.

16 Disney, “End of Shamsky Era.”

17 Disney, “End of Shamsky Era.”

18 Disney, “End of Shamsky Era.”

19.Shamsky and Zeman, 94.

20 Shamsky and Zeman, 96.

21 Shamsky and Zeman, 99.

22 Shamsky and Zeman, 102.

23 Dick Young, “Disabled and Displaced … Art Swings Back,” New York Daily News, July 19, 1969.

24 Dick Young, “Shamsky Plays With Pain,” New York Daily News, March 2, 1970.

25 Allen, 204.

26 Shamsky and Zeman, 155.

27 Allen, 201.

28 Andy Epstein, “Out of Left Field: With a Miracle Met,” Mets Inside Pitch, May 2007: 21.

29 Steven Marcus, “Art Shamsky details Tom Seaver’s health issues in new book,” New York Newsday, March 3, 2019.

30 “World Series Champion Art Shamsky On 1969 Mets, Tom Seaver & New Book,” CBS New York.com, March 20, 2019.

31 “World Series Champion Art Shamsky On 1969 Mets, Tom Seaver & New Book,”

32 Shamsky and Zeman, 186.

Full Name

Arthur Louis Shamsky

Born

October 14, 1941 at St. Louis, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.