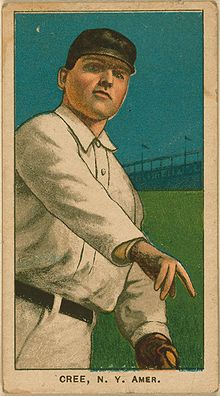

Birdie Cree

A school teacher, a football player, a Penn State graduate, a professional ball player, and finally, a bank cashier, Birdie Cree spent his major league career with only one team, while witnessing the rise and fall of managers Kid Elberfeld, George Stallings, Hal Chase, Harry Wolverton, Frank Chance, and Roger Peckinpaugh. Batting and throwing right handed, the speedy 5’6″ 150-pound Cree was described as a “robust walloper”, and one who could “throw as far as anyone his size.” During his eight-year major league career, Cree established the Yankees franchise record (later broken) for most triples in a season, with 22 in 1911, and his 48 stolen bases that year remain the eighth-highest figure in franchise history.

A school teacher, a football player, a Penn State graduate, a professional ball player, and finally, a bank cashier, Birdie Cree spent his major league career with only one team, while witnessing the rise and fall of managers Kid Elberfeld, George Stallings, Hal Chase, Harry Wolverton, Frank Chance, and Roger Peckinpaugh. Batting and throwing right handed, the speedy 5’6″ 150-pound Cree was described as a “robust walloper”, and one who could “throw as far as anyone his size.” During his eight-year major league career, Cree established the Yankees franchise record (later broken) for most triples in a season, with 22 in 1911, and his 48 stolen bases that year remain the eighth-highest figure in franchise history.

Born on October 23, 1882, 50 miles south of Pittsburgh in the small town of Khedive, Pennsylvania, William Franklin “Birdie” Cree was the adopted son of Levi Cree. After finishing public school, he attended Southwestern State Normal School at California, Pennsylvania in 1901, and graduated two years later as a fully qualified teacher. He began teaching eighth grade in the California city public schools, while also playing shortstop and third base with the Normal School baseball team. He also starred as a quarterback for the football team, figuring it would improve his speed. Word of his football skills spread and Cree received a scholarship to Penn State in the fall of 1904 after being discovered by Penn State athletic director “Pop” Golden.

That summer before attending Penn State, Cree played baseball for the Washington (Pennsylvania) Patriots of the outlaw Ohio-Pennsylvania League. While sliding head first into second base, he dislocated his collarbone. Then in the fall after only 3 days of football practice, he again dislocated the same collarbone and was out for the year.

During the spring of 1905, Cree began to play baseball for the State team. It was here he first earned his nickname of “Birdie.” Cree recalled, “In my first game for State, I hit everything but the umpire, getting a home run, triple, double and single. A classmate jumped up and yelled: ‘he’s a bird–that’s what he is.’ The name stuck and eventually became ‘Birdie,’ possibly also because I was so small.”

To make extra money, Cree began playing baseball for a team in Sunbury, Pennsylvania. Still in school, and not wanting to appear under his own name, he played under the name “Burde” and was the top hitter on the team. While in Sunbury, Cree met his future wife, Mary Edna Keefer.

The following summer Cree played in Burlington, Vermont along with several other future major leaguers. In 1907, Cree was persuaded by Penn State coach Jimmy Sebring, an outfielder for the Williamsport club of the Tri-State League, to join the Millionaires. Cree played shortstop and batted .297 over the season, helping lead Williamsport to the championship.

At the end of the season, Cree, still known as Bill Burde, was purchased by Connie Mack of the Philadelphia Athletics, but was left in Williamsport for another year. With a surplus of shortstops, Manager Harry Wolverton moved Cree to the outfield. Before the 1908 season was over, the Detroit Tigers acquired Cree from the Athletics and traded him to the New York Highlanders on condition that George Moriarty would be sold to the Tigers before the beginning of the next season. On September 17, center fielder Birdie Cree made his major league debut, playing center field and batting third.

On June 24, 1909 while facing Cy Morgan, Cree hit his first home run. It was also the first home run ever hit out of Shibe Park in Philadelphia by a right handed batter. “I drove that ball over the right field wall and into Matt Kilroy‘s saloon on the corner of Twentieth Street and Lehigh Avenue. I know it bounced into the barroom because that is where I got the ball. I still have it.” Cree finished the year with a .262 batting average in 104 games.

On April 22, 1910, Cree was hit in the head by a Walter Johnson fastball. Knocked unconscious, he was carried from the field, yet returned to the lineup the next day. Finishing the season with a .287 batting average, he led his team with 16 triples, and tied for the team lead with 4 home runs and 73 RBI.

With an abundance of outfielders in 1911, new manager Hal Chase tried Cree at shortstop, declaring that “he must have Cree on the big team somewhere when the players return north.” But Cree soon moved back to the outfield–playing left now instead of center–and had the best season of his career. He not only led his team in almost every category, but was in the top five of the American League in batting average (.348), slugging (.513), total bases (267), triples (22), stolen bases (48), and extra base hits (56). His four home runs, all solo shots, again tied for the team lead. In one game against the Browns, Cree stole four bases. As the season wound down, Cree once again tried playing shortstop for a couple days, but proved a failure, declaring that he would never again try his hand in any infield work. Cree finished sixth in the Chalmers Award voting for most valuable player that year.

After contracting a severe cold in Atlanta during spring training in 1912, Cree was sent home in advance of the team. He played the opening series with Boston, but Cree was so ill, he was taken to a hospital. Upon his return, Cree continued his pace of 1911, batting .332 with 12 stolen bases and six triples after only 50 games. Then, on June 29, Cree’s wrist was broken on a pitch thrown by Buck O’Brien of Boston, forcing him to miss the remainder of the season.

With his wrist still bothering him, Cree’s batting suffered throughout the 1913 season, dropping his average to .272. However, he led the league in fielding percentage for the first time, making only three errors in 259 chances while also recording five double plays as a left fielder. His only home run was a grand slam, one of only five hit that year in the American League.

As the team trained in Bermuda for 1914, Cree reported out of shape and was unable to play to his ability. “I was overweight and patrolling the outfield in a rubber shirt, a sweat shirt and a sweater,” Cree later recalled. “The grass in the outfield was up to my knees. Somebody hit a fly my way and I went after it, but before I had gone ten feet I was tangled up in the bulrushes and the ball fell safe. After the inning was over, I went to the dugout. Manager Chance was sitting on one end of the bench. I knew he was angry but he didn’t say anything for a minute or two. Then, looking over at me, he rasped: “Birdie, why in the hell don’t you lay down out there? You’d cover more ground than you do standing up!”

Unable to trade him, Cree was released to Baltimore of the International League. Manager Jack Dunn signed Cree to a $4,500 contract, teaming him up with other former major league players Bert Daniels, Neal Ball, Freddy Parent, and future stars Babe Ruth and Ernie Shore. Cree claimed that he had been offered $30,000 over three years by the Pittsburgh club of the Federal League, and had been presented a certified check for half the amount in advance. But after realizing that Cree was out of shape, the Feds broke off negotiations.

By the middle of the 1914 season, the Orioles were ahead by 17 games with a revived Cree batting .356 along with his usual collection of extra base hits. But the team was suffering badly at the gate due to competition from the local Federal League team, and Dunn began to sell off his players. Cree was sold back to New York on July 9–two days before teammate Ruth was sold to the Red Sox–and finished the season batting .309 in 77 games.

As in 1912, Cree was again injured after an outstanding season. In April of 1915, while warming up before a game, Cree was hit in the face by a ball, breaking his nose. This injury, along with his weight gain, eventually forced Cree into retirement. He finished the 1915 campaign with a .214 average, but posted a robust .353 on-base percentage in 74 games.

After being released in February of 1916, Cree began working as a mail clerk at the First National Bank in Sunbury, Pennsylvania. Although his salary was a lot less than during his ball playing days, he “didn’t mind beginning at the bottom.” Eventually he moved on to the bookkeeping department, then teller, and finally cashier. He continued his love of sports, playing tennis and learning golf. Becoming the leading golfer at his country club, Cree won the club championship five years in a row. He was also an outstanding billiards player for the Masonic Temple Club. An avid pinochle player, he also enjoyed the music of Franz Liszt and Irving Berlin. Cree died November 8, 1942, after a ten week illness. He was buried in Pomfret-Manor Cemetery in Sunbury.

Note

This biography originally appeared in David Jones, ed., Deadball Stars of the American League (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, Inc., 2006).

Sources

Birdie Cree’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library

Baseball Encyclopedia, MacMillan

New York Times

Jim Reisler. Before They Were the Bombers–The New York Yankees’ Early Years, 1903-1915. McFarland, 2005.

Martin Kohout. Hal Chase–The Defiant Life and Turbulent Times of Baseball’s Biggest Crook. McFarland, 2001.

Full Name

William Franklin Cree

Born

October 23, 1882 at Khedive, PA (USA)

Died

November 7, 1942 at Sunbury, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.