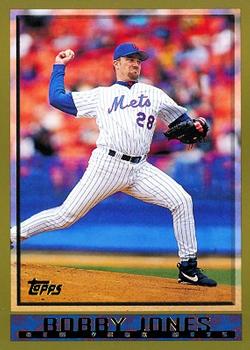

Bobby Jones

Robert Joseph “Bobby” Jones was a thinking man’s pitcher. He didn’t possess the flamethrower fastball of the Hall of Fame pitcher to whom he was most often connected through geography — fellow Fresno, California, native and New York Met Tom Seaver. But Jones’s cerebral approach served him well throughout a 10-year career in the majors (1993-2002). His professional highlight was one of the best postseason games ever pitched: a one-hitter to clinch the 2000 National League Division Series.

Robert Joseph “Bobby” Jones was a thinking man’s pitcher. He didn’t possess the flamethrower fastball of the Hall of Fame pitcher to whom he was most often connected through geography — fellow Fresno, California, native and New York Met Tom Seaver. But Jones’s cerebral approach served him well throughout a 10-year career in the majors (1993-2002). His professional highlight was one of the best postseason games ever pitched: a one-hitter to clinch the 2000 National League Division Series.

Jones was born on February 10, 1970, in Fresno, California, one of three children born to Bob Jones, a welder, and Cheryl, an insurance claims adjuster. His father played fast-pitch softball and worked with his son to help him build his baseball skills. “My father taught me how to pitch at an early age,” Bobby Jones said. “How to be mentally tough and not let things affect you. I can still remember in the backyard when I was five or six years old, my dad saying. ‘Okay, Jim Rice is up. Runner on first. What are you going to do?’”

Jones was a good baseball player at Fresno High School, but getting drafted was “never a thought.” He thought his future might be in music — he was a drummer in a band named “High Voltage.” Yet he was good enough to earn a baseball scholarship to Fresno State. Jones remembers that when he got to college in 1989, there was a pitching depth chart list in the dugout. In his freshman year, he was the last pitcher on that list — until one game in which he escaped a bases-loaded, no-outs jam. It didn’t take long for him to become the team’s closer. He set a school record with 11 saves and led the team with a 2.15 ERA.1

By his junior year, Jones had gone from closer to staff ace. He became known for his big curveball and his ability to get through innings quickly. “Day in and day out, Bob has been about as consistent as any pitcher we’ve had here,” head baseball coach Bob Bennett said at the time. “There aren’t too many guys I’ve had who prepare for a game better than Bob.”2

“My college coach taught me how to mature,” Jones said. “Maturity on the field and maturity off the field says a lot about you. You look at the older guys in high school, college, the big leagues, their work ethic and how they got things done, and how they carried themselves off the field.

My dad and my high school coaches got me grounded on pitching mechanics and then my college coach fine-tuned that.”

In 1991, Jones went 16-2 with a 1.88 ERA and pitched 16 consecutive complete games, including four in a 13-day span. The last of those was a 2-1 loss to eventual national champ Florida State on three days’ rest in the College World Series, where Fresno State, the Big West champions, finished tied for fifth. That summer, he was drafted in the first round by the Mets, 36th overall. It was a supplemental pick the Mets received for losing superstar outfielder Darryl Strawberry to the Dodgers in free agency. “He’s not overpowering, but he has three or four pitches and knows when to use them,” said then-Mets director of scouting Roland Johnson.3

Jones pitched in five games with the Mets’ Columbia affiliate in the Class-A South Atlantic League and helped them win the championship by going 3-1 with a 1.85 ERA. The next season he moved to Double-A and the Binghamton Mets, where he stayed the whole season. He went 12-4 with a 1.88 ERA and pitched a complete-game win in the deciding game of the league’s championship series. Perhaps foreshadowing his peak moment that day, Jones retired 22 of the last 23 Canton-Akron Indians hitters to end the game.4

Earlier that season, he had pitched for the Mets in the Hall of Fame Game in Cooperstown. It coincided with the induction of Mets legend and fellow Fresno High graduate Tom Seaver into the Baseball Hall of Fame. The two met for the first time during induction week. “Tom was a quiet reserved guy who liked to keep to himself,” Jones said. “He just loved to talk about the game, loved the game so much.”

In 1993, Jones moved to Triple-A Norfolk, where manager Clint Hurdle helped groom him for the major leagues. He was called up by the Mets in mid-August and made his big-league debut on August 14 in Philadelphia against a Phillies team that entered the day 74-42, 34½ games better than the Mets. With more than 46,000 fans in the stands, Jones had every reason to be nervous, but he handled the moment well, allowing five runs (one earned) in six innings of the Mets’ 9-5 win.

“I was nervous, but I felt good and slept well,” Jones said. “I remember the first batter, Len Dykstra, hit the ball so hard over my head. Ryan Thompson came in from center field and caught it.” Mets manager Dallas Green said, “He just goes about his business. He’s not a screamer and a yeller. I liked what I saw.”5

Jones made eight more starts that season and finished 2-4 with a 3.65 ERA. In all, he logged 227 2/3 innings between Triple-A and the majors. Besides his debut, his most memorable start was his last of the season, in which he went 10 scoreless innings (throwing 143 pitches) against the Cardinals in a game that the Mets won, 1-0, in 17 innings. Though the 1993 Mets finished 59-103, Jones learned a lot from the team’s top pitchers. “Dwight Gooden and Bret Saberhagen were good guys that I looked up to, watched how they did things and saw that you do it this way,” Jones said. “It’s not like we hung out all the time, but we were baseball buddies. They’d take me to the side in the outfield during BP and talk about how they would pitch a hitter.”

Jones evolved into the team’s second-best pitcher behind Saberhagen by the end of the strike-shortened 1994 season. He went 12-7 with a 3.15 ERA. That November he married Kristi Platt.

With a fastball that was usually in the mid- to high 80s, Jones took a reasoned approach to pitching. “Everyone thinks, ‘How do you go out and throw seven innings and give up one run and then the next day go five innings and give up six runs?’” I think I pitched the same a lot. But there were times when a ground ball that could be hit to shortstop is hit in the hole. How do you control that? Sometimes you have an umpire who gives you the corner, sometimes you don’t. Sometimes line drives are caught. Sometimes they’re in the gap and score two runs. I chose not to overthink it. I tried to go out there with my best stuff every time. Some days you had it and got beat. Some days you didn’t have it and won.”

He was also someone who kept his emotions in check on the mound. “That’s something my dad instilled within me,” Jones said. “You never show your opponent that you’re beat or you’re beating them. You can have that fire inside. Just don’t show that. People used to say they couldn’t tell if I was up 10-0 or down 10-0. Against Atlanta, I gave up eight runs in the first inning, kicked a container of bubble gum in the air and it hit me in the face with the TV camera right there,” Jones said. It embarrassed me. I said that’s not who I am and I’ve gotta be better than that. Kids are watching. I don’t want them to see that.”

In 1995, Jones made the first of three Opening Day starts. He won 10, 12, and a career-high 15 games from 1995 to 1997, pitching at least 190 innings in each season. In 1997 he was one of the best pitchers in baseball for the first two months of the season: 11-2 with a 2.22 ERA in his first 13 starts, NL Pitcher of the Month for May, and his first and only All-Star selection. He worked a scoreless eighth inning in the All-Star Game, which the AL won, 3-1. Jones wasn’t known for striking out hitters, but he whiffed both Ken Griffey Jr. and Mark McGwire in the inning. “I remember going in the dugout, sitting down and saying ‘Phew, that was kind of cool,’” Curt Schilling looks over at me and says. ‘You know what? That’s one son who’s going to be able to go to his buddies and say, ‘My dad struck out McGwire and Griffey Jr. back-to-back.’ That’s always stuck with me.”

Jones finished 1997 15-9 with a 3.63 ERA, then tailed off to 9-9. After injuries limited him to 12 starts in 1999, he was left off the postseason roster and took a step back in the Mets’ rotation. The 2000 season started poorly; he allowed 11 runs in 6 2/3 innings in his first two starts, then suffered a torn calf muscle that caused him to miss a month. Upon his return, he was hit hard in

His next five starts; after allowing seven runs in 4 2/3 innings against the Yankees, his ERA stood at 10.19. Mets management decided to demote him to Triple-A, though they needed his permission to agree to the move. He agreed immediately.“I think that was a great day. It was a tough day, full of emotion. I said to them that I could see why they were asking me to do that. I said, ‘Absolutely. I’m not helping anybody here. Let me figure out what I need to figure out in a less stressful situation where I’m not hurting the team.’”

Jones was recalled two weeks later. Coincidentally, the Mets made room for him on the roster by demoting a left-handed pitcher named … Bobby Jones.6 Thirteen days later he was back in Shea Stadium, where he held the Pirates to one run and struck out eight in eight innings in a 12-2 Mets rout. “I had something to prove tonight,” he said after the game.7

Jones went 10-3 with a 3.69 ERA in his last 19 starts of the season. That earned him a spot on the Mets’ NLDS roster against the Giants, though Jones’s wife found out that he would start the potential clinching Game Four of the series before he did.

“My wife walked by [Mets manager] Bobby [Valentine] in the tunnel after Game Three and said, ‘If you give my husband the ball, he’ll have the game of his life,’” Jones said. “Shortly thereafter, he [Valentine] said ‘You’ve got the ball.’ And he told Mike Hampton he wanted him to fly to San Francisco (in case of Game Five). Mike said ‘No, I’m staying here to celebrate.’”

The game was a big deal not just to the Mets and Giants but to the city of Fresno because Jones would be pitching against his friend and fellow Fresno resident, Mark Gardner. “Everybody was watching that game at someone’s house, restaurant or whatever, watching these two buddies play in such an important game. We’re still friends to this day.We were taught the same way by the same college coach,” Jones said. “We looked at each other and picked apart our tendencies and things we needed to work on during the offseason. He had a golf tournament that he would put together. We would pick a charity every year. We would do a dinner and have a golf tournament. His wife was diagnosed with cancer. She spent a lot of time at Stanford Medical Center. We decided let’s start a foundation, get a board. We don’t have to just give the money away. We can wait for a situation, every year give a chunk to Stanford, and sponsor some families at Christmas for people that aren’t able to get their kids presents.”

Kristi Jones had told her husband that he would pitch a three-hitter or better. She was almost exactly on the mark.8 The Giants went 1-2-3 in the first inning, with Barry Bonds striking out on a fastball that was up and in to end the frame.9 “I felt good throwing against him,” Jones said of Bonds, who entered the day 8-for-37 in his career against him. “I knew where I could get him out when I needed to. With my slow curveball, it started so high, I could adjust his eyes. He saw fastballs letter-high or higher and he swung at a lot of them. Especially ones in. You try to slow the bat down and then speed it up.”

The Mets took the lead in the bottom of the first inning. Third baseman Robin Ventura followed a Mike Piazza walk with a first-pitch two-run home run. It stayed 2-0 until the fifth when the Mets scored two to make it 4-0. Meanwhile, Jones had not allowed a base runner until the fifth, when the Giants left the bases loaded without scoring. He then cruised to the finish, retiring the Giants in order in each of the last four innings, with the opposition never coming close to getting a hit. As the game went along, the home crowd at Shea — more than 56,000 — began to chant his name and cheered every pitch. “They cheered Bobby Jones of Fresno like he had never been cheered in his life,” wrote Mike Lupica in the New York Daily News. “Cheered him like he was Seaver.”10

“When you’re on the mound, you don’t recognize [the fans chanting your name], but watching it years later, that was like ‘whoa,’” Jones said. “That’s pretty cool. Anything can happen. That’s why this game is so great.”

Two decades later, Jones looked back with the same level of satisfaction. “All of that emotion, of failing to stay up in the first part of the year, going to the minor leagues, they had the confidence in me to give me the ball and a teammate saying I’m not going to San Francisco because we’re winning, and realizing I finally helped my team do it. That was one of the best feelings ever.”

Jones became the fourth pitcher to allow one hit or fewer in a postseason game (there have been two more such games through the 2020 season).11 The one hit is the fewest allowed in a Mets postseason game. It was a testament to Jones’s pitching approach. “You know people like to look at the speed gun and say ‘Gee, he’s [only] throwing 84 miles per hour,” Valentine said. “But he complements that with a changeup, curveball, cut fastball and slider [that] can be a torment to hitters.”12

Jones made two more starts that postseason, neither of which went as well. In Game Four of the NLCS against the Cardinals he allowed six runs in four innings but got a no-decision in the Mets’ 10-6 win. Then in Game Four of the World Series against the Yankees, he allowed three runs in five innings in a 3-2 loss.

The most notable moment of the latter game came on the first pitch Jones threw: Derek Jeter homered. “The night before the game, my sister-in-law was with us and in the car, she asked me ‘How come no one ever swings at the first pitch of the game?’” Jones recalled. “I said ‘It’s the leadoff hitter, they’re trying to set the tone. They’re going to make the pitcher throw some pitches. You don’t want to make a first-pitch out.’ I give her the whole spiel.

“The Yankees moved Jeter up to leadoff.13 I talked to Mike [Piazza] and said, ‘Maybe we should go first-pitch curveball.’” And we decided let’s make a good pitch down and away. Of course, it wasn’t down and away. It was right middle-in. I told my wife the story after the game. She was so mad at her sister.”

Jones became a free agent that offseason and was not happy when general manager Steve Phillips asked him to take a pay cut. Jones had a hard time finding a new home and finally signed with the San Diego Padres, who offered an incentive-boosted one-year deal with an option year. The move put him within a six-hour drive of his family’s Fresno home and allowed him to fill a mentoring role for the team’s young pitchers like Jake Peavy.

Jones got off to a good start in 2001, pitching to a 2.67 ERA through 10 starts. But through a dozen starts, he was 2-8; the Padres’ offense had given him less than three runs of support per game. He finished 8-19 with a 5.12 ERA. He got along well with manager Bruce Bochy and declined an offer to stop pitching as he neared 20 losses. “I said no, I’m not a quitter. If I was one of the guys who was cracking and showing emotion when my young shortstop made an error, then I wouldn’t have been doing my job for those young kids.”

In 2002, Jones re-signed and again started well, but dealt with rib cage, elbow and back injuries. The Padres released him on September 4. Jones says he could have signed with the Colorado Rockies to finish out the season pitching for his former minor league manager, Hurdle, as part of a tryout for 2003. But Jones and his family took a vote. The verdict was unanimous against pitching, so he retired. “I don’t regret it one bit,” he said.

Jones became Mr. Dad. He went on school trips and coached his three children in Little League. He indulged his other passions — cooking and wine. One of the reasons Jones had enjoyed his time in New York was because he loved touring the city’s restaurants. He made quick friends with the staffs. “I’m a foodie. I would go back with the chefs and the owners and learn how to cook.”

Jones found a new area to work after baseball: developing barbecue sauces. The first was called Sloppy Jon’s; now he has a gourmet offering, 142 BBQ (named for the optimal temperature at which meat cooks). He also works with a chemist friend to make his own wines, which he gives to friends and keeps for meals, similar to Seaver, who had established a winery in California.

“I think it has a lot to do with who I am, like it was with baseball,” Jones said. “Thinking, learning, outsmarting somebody. I remember going to restaurants and thinking ‘What is in that?’ And then going home and trying to recreate it. And dumping it out, trying again. When you finally get it — wow. Making something that’s really good and knowing the process to make it … there’s a lot to it.”

Jones returned to Fresno State as interim pitching coach in 2006. There, he worked with future major leaguers Justin Wilson and Doug Fister. But in order to continue, Jones would have had to finish his degree and the time commitment was too great. So he resigned and began giving lessons to local school teams and kids in his free time.14 As of January 2021, Jones lives in Fresno and is comfortable with how his career turned out.

“I want to be remembered as a competitor who did as well as he could with the talent that he had,” he said. “I knew I wasn’t going to be a dominating guy. I had to be really sharp. At times I was and at times I wasn’t.”

Jones finished with an 89-83 record and a 4.36 ERA. He posted the eleventh-highest Wins Above Replacement (per Baseball-Reference).15 And he had one day that he and many baseball fans will remember forever.

Last revised: February 4, 2021

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Bobby Jones for his memories. All quotes from Jones, other than those shown in the notes, are from an interview done by the author on November 13, 2020.

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Norman Macht and fact-checked by Alan Cohen.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted www.baseball-reference.com and www.retrosheet.org.

Notes

1 Jones held the school’s single-season saves mark until the 2008 season.

2 “Jones Drops Smart Pitches On Foes,” Fresno Bee, May 10, 1991: D1.

3 Terry Betterton, “Jones Has Pitching Instincts, Mets’ Scouting,” Fresno Bee, August 7, 1991: C16.

4 Matt Weinstein, “Bobby Jones set B-Mets Franchise on Winning Path,” Binghamton Press & Sun-Bulletin, August 30, 2014.

5 Steve Serby, “Jones A Winner Right At Start,” New York Daily News, August 15, 1993: 49.

6 Robert Mitchell Jones was an African American lefty. The namesakes also pitched against each other on May 11, 1999 with Bobby J. losing to Bobby M. (then with the Colorado Rockies), 8-5.

7 “Major Relief After Minors,” Asbury Park Press, June 24, 2000: D1.

8 Ian O’Connor, “Break Out The Bubbly,” The Journal News, October 9, 2000: C1.

9 I rewatched the game, which can be found at this link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TMg1o5qzbsc

10 Mike Lupica, “Mets Take a Giant Step,” New York Daily News, October 9, 2000. 60.

11 You can see the list here: https://stathead.com/sharing/dkHUY

12 Pete Caldera, “Jones Applies Finishing Touch,” The Record, October 9, 2000: D1.

13 It was the only game of the series in which Jeter batted leadoff.

14 You can see an example of who Jones is teaching at this link: https://www.thefeather.com/2018/01/16/retired-mlb-pitcher-assists-campus-baseball-program/

15 You can find the list here: http://bbref.com/pi/shareit/PxaiR

Full Name

Robert Joseph Jones

Born

February 10, 1970 at Fresno, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.