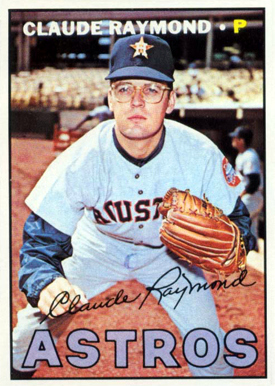

Claude Raymond

If it is true that every boy born in the United States comes with a baseball glove on his hand, in Quebec children are more likely to enter the world wearing a pair of ice skates. Claude Raymond, the first baseball player from Quebec ever selected for a major-league All-Star Game, was no exception.

If it is true that every boy born in the United States comes with a baseball glove on his hand, in Quebec children are more likely to enter the world wearing a pair of ice skates. Claude Raymond, the first baseball player from Quebec ever selected for a major-league All-Star Game, was no exception.

Like all young Quebecers in the 1940s, Raymond spent his days on the neighborhood rink, where he would seek to imitate the moves of Maurice (Rocket) Richard, the star of the National Hockey League’s Montreal Canadiens. “During the Christmas holidays,” he says, “I would leave the house early in the morning with my skates already on my feet. At noon, I didn’t even take them off for lunch. My mother would cover the floor with newspapers right to the table. At suppertime, it was the same thing. ”[1]

As a boy born in Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu on May 7, 1937, Raymond was nourished on hockey day and night. But he was also realistic: he recognized that he would never score 50 goals in 50 games, as the Rocket did in 1945. On the other hand, there was baseball, where he could literally tear the cover off the ball. He hit with such force that, at a very early age, even though he was right-handed, he was made to bat from the left side, to ensure that his line drives would not break the stained-glass windows in the church next to the playground.[2]

Raymond was fortunate to grow up in a town where baseball, along with hockey, had long been considered a religion. Thanks to its proximity to the U. S. border, Saint-Jean was one of the first municipalities in Quebec to take up baseball. In 1869, the Crescent became the first team to be formed off the Island of Montreal.[3] Saint-Jean later placed a club in the Provincial League, when in 1898 the French-speaking community put together an amateur circuit to counter the professional English-speakers of the Montreal Royals.

But it was in the 1940s that baseball in Saint-Jean experienced its golden age. Following the end of World War II, as military personnel returned home, a surplus of baseball players developed. Many were drawn to the Mexican League, then seeking to become something of another major league. When this venture failed, these players – some of them now banished from Organized Baseball – followed the lead of Roland Gladu and Jean-Pierre Roy and signed on with the Provincial League, which was not part of Organized Baseball’s structure at the time. Between 1947 and 1949 Saint-Jean welcomed a number of stars from elsewhere, including Roy, Myron “Red” Hayworth of the old St. Louis Browns, the Japanese-Canadian Kaz Suga, and such veterans from the Negro Leagues as Quincy Barbee and Terris McDuffie.

The Braves were the main attraction in town and Claude Raymond was one of their most loyal fans. He says in his autobiography that by the age of seven he was earning his way into games by returning foul balls that he caught outside the stadium. He soon became a popcorn vendor, then team mascot, and by the time he was 12 was occasionally even asked to pitch batting practice.[4]

It was in this postwar environment, in a town passionate about baseball, that Claude Raymond came into his own. In 1953, while trying out with the Drummondville Royals of the Provincial League, he began to stand out from the others. The Royals tried to sign him on the spot, but were forced to withdraw the offer when they discovered that their brilliant pitcher was not 17, as he had claimed, but 15 years old.[5]

Raymond next tried his chances with a Montreal junior league, regularly hitch-hiking back and forth from Saint-Jean. After he had pitched two no-hit, no-run games, the scouts started to notice him. Following his second season of junior ball, he signed a contract with the Brooklyn Dodgers organization. But the transaction had to be canceled because Raymond was still in school and the Dodgers had forgotten to seek the special permission required to sign him. Finally, Milwaukee Braves and former Provincial League star Roland Gladu succeeded in getting his name on the dotted line.

In March 1955, Raymond struck out for the United States along with several other French-speaking protégés signed by Gladu (Yvan Dubois, Ron Piché, and Bobby Laforest). Raymond, who spoke only French, set himself the goal of learning 10 new English words every day.[6] Unlike many French-Canadians who, in the 1940s, ’50s, and ’60s, returned to Quebec because of problems they encountered with the language, Raymond did not experience homesickness.

Soon he was working his way up through the minor leagues and establishing himself as a relief pitcher, a specialization rare for that time. His first assignment was with West Palm Beach in the Class D Florida State League, where he posted a 13-12 record with a strong 2.60 ERA, starting 27 games and throwing a full 194 innings. Advancing to Class B with Evanston in the Three-I League, in 1956 he was converted to relief and started just four games, but ending the year with a 9-3 mark and a 2.57 ERA. In 1957, at Jacksonville (South Atlantic League, Class A), he set a league record for the number of games pitched (54, only one of which was a start). But in 1958, an inflammation of the shoulder put the brakes on his development and the Braves decided not to protect him from the intra-league draft. “I was so hoping I would be drafted that I spent two hours in prayer at Notre-Dame-Auxiliatrice Church,” he recounts in his autobiography.[7]

Raymond was drafted by the Chicago White Sox and soon received a call from owner Chuck Comiskey, welcoming him to the White Sox organization. His prayers now answered, Raymond had every reason to believe that his career was about to receive a new shot in the arm. And a few weeks later he found himself at training camp in Tampa in 1959 with Nellie Fox as his roommate, working under the watchful eye of manager Al Lopez. He remembers that Lopez, “at one time, told everyone that I had the best curveball in the camp. All of a sudden the season started and I was in the major leagues![8]

“It was a wonderful day for me. I never thought that I would reach the majors so quickly,” he relates in his autobiography. “I spent a month with the White Sox. Manager Lopez called on my services three times. The first time was in relief in a lost cause situation against Kansas City. The first batter I faced was Bob Cerv … and I hit him with my first pitch.”[9]

Following the two inning of work in his April 15 debut, by mid-May Raymond had pitched only four innings and had given up four earned runs. “There was a possibility that the White Sox would cut John Callison, but, unfortunately, I was the one they released,” he says in his autobiography.

In keeping with the rules governing the major-league draft, the Quebec pitcher was returned to the Braves. “I took comfort from the notion that the White Sox released me because they already possessed an excellent arsenal of pitchers, including Early Wynn, Billy Pierce, Bob Shaw, Dick Donovan, Turk Lown and Gerry Staley,” he says.[10]

Now back in Triple-A, at the Braves’ Louisville farm team, the 22-year-old Raymond found himself in the company of three other Canadian players, Ron Piché, Georges Maranda, and Ken MacKenzie. However, after only eight innings of work experienced another demotion, to Double-A Atlanta, where he finished the season … as a right fielder!

After posting a 9-9 record for Sacramento of the Pacific Coast League in 1960, Raymond returned to the majors as a pitcher with the Milwaukee Braves in 1961. There he picked up his first win and also struck out two of his childhood idols, Dodgers Gil Hodges and Duke Snider. Unfortunately for Raymond, though, the Braves acquired veteran hurler Johnny Antonelli and Raymond was handed his ticket to Triple-A Vancouver. “I was so distraught that my parents, who were on holiday, came to Milwaukee to offer me encouragement,” he says in his autobiography.[11]

The return to the minors was difficult to accept. That winter Raymond considered stepping away from the game. “I was disillusioned. I wanted to recover my balance. I spent my time skiing and playing hockey. I was taking great risks. I don’t know how many nasty falls I took on the hills that winter!”[12]

Nevertheless, in 1962 he went to spring training with the Braves and was called up in mid-June. He registered an earned run average of 2.74 in 26 games and was selected the organization’s Rookie of the Year. However, when Bobby Bragan arrived as manager in 1963, things once again began sliding off the rails. Bragan thought he could win the championship with only eight or nine pitchers and Raymond found himself nailed to the bench for 27 straight days (as did Frank Funk, for 28 days).

“In those days Milwaukee was a superb town, very welcoming,” he told a visiting group of Quebec journalists in 1998. “Among other benefits, we would receive a case of beer every week, courtesy of the most important employer in the city (Miller). … We were supplied an automobile, full of gas, a carton of cigarettes, dairy products. We could even arrange to have our clothing cleaned for free.”[13]

At the end of the 1963 season the National League held a special draft to reinforce the feeble New York Mets and Houston Colts. Raymond was drafted by Houston (the price was $30,000) and enjoyed one of his best seasons. (5-5, 2.82). “I was living at Surrey House and Kenny Rogers was my neighbor. At night, he was a singer in a club with the Bobby Doyle trio. You required a key to enter after midnight and the players went there to listen to him. On Sundays, everything was shut down and we would party out by the side of the pool,”[14] recounted Raymond at the 2007 Western Festival in Saint-Tite, Quebec, where he reconnected with Rogers.

In 1965, still with Houston, Raymond started seven games before ending the year in the bullpen with a respectable 7-4, 2.90 record. At midseason in 1966, now serving as a short-relief specialist, he led both leagues in earned–run average (1.35). Dodgers manager Walter Alston selected Raymond for the All-Star Game squad, a first for a Quebec-born player. (At that time, the teams were chosen by the managers, coaches, and players.) “I was not allowed to tell anybody. I did call my parents and they drove to St. Louis,” he said in 1992.[15]

However, much like the situation when his parents had driven to Milwaukee, Raymond remained on the sidelines. Alston was content to stick with only four pitchers that day. “I was disappointed but that was the way things were back then. Alston did have me warm up when Sandy Koufax threw three consecutive balls in the third inning. It was 117 degrees on the field (in St. Louis), and so that didn’t take me very long.”[16]

This was the high point of Raymond’s career. In 1967, he returned to the Braves, by now in Atlanta, in exchange for Wade Blasingame. This time, changing clubhouses only involved a few steps, as Atlanta was visiting Houston that weekend. Raymond earned a save on the Friday night and was the winning pitcher on Saturday. He ended the season with Atlanta in fine fashion (4-1, 2.65, after going 0-4 for Houston) and was equally outstanding in 1968 (3-5, 2.83).

On February 1, 1969, Raymond married Rita Duval. As was fitting, the wedding cake was shaped to look like a ballpark. On May 16 the Braves sent him into the fray at Jarry Park against the new Montreal Expos. He recalled, “I was nervous when the stadium announcer called out: ‘And now, pitching for the Atlanta Braves … number 36 … from Saint-Jean, Quebec … Claude Raymond.’[17]

“I have never felt more at home than I did that night. I was very nervous. For the very first time, I was shaking on the mound. I actually dropped the ball, my emotions were so powerful.” In the end, after the right-handed reliever had earned an 11th-inning save, the spectators gave him a standing ovation. Then, on August 19, Raymond joined the Expos in a cash deal, becoming the first Quebecer to wear the team’s multicolored uniform. (He was followed by Denis Boucher and Derek Aucoin in the 1990s.)

Although the Braves were in first place and the Expos in last place, Raymond was all smiles when he heard the news. “I was delighted to change teams. With Atlanta, I hardly pitched at all. And for a relief pitcher there is nothing worse than a lack of action.”[18] Further, he would now be living closer to both his and Rita’s families. At the time she was five months pregnant with their daughter Natalie.

Following a nondescript end of the season, Raymond dreaded spring training in 1970. He was experiencing arthritis in the index finger on his right hand – his pitching hand – and manager Gene Mauch seldom turned to him. In effect Raymond became the last pitcher called upon during spring training and the last to be utilized in the regular season.[19]

But bit by bit, as other Expos relievers struggled, Raymond’s workload increased. At the beginning of June he retired 25 of 27 batters over five games, registering five consecutive saves.[20] “I was in really good shape,” he told writer Jim Shearon some years later. “I wanted to prove that if I was in Montreal, it wasn’t because I was a French-Canadian, but because I could still pitch. That was my most satisfying season.”[21]

Claude Raymond became an idol for young Quebec athletes and was as popular as the best players on hockey’s Montreal Canadiens. In January 1971, he benefited from this attention by signing the most lucrative contact of his career, and then took off for Europe with his family. The heavens were aligned for an exceptional 1971 season, but then the pitcher from Saint-Jean slipped on a piece of wet ground at spring training and an ankle infection set in. This injury opened the door for a young Mike Marshall to stake his claim on the role of number one reliever for the Expos, one that he never relinquished.

As for Raymond, everything began collapsing all around him. During one 17-day period in midseason he was credited with five losses. The Expos kept him on for the balance of the season (1-7, 4.66) but released him after the season. During the winter he approached the Mets, Yankees, Cubs, White Sox, and Tigers, but no one was interested. Raymond’s playing career was over. He ended with a lifetime record of 46-53 and an earned run average of 3.66 over 449 games.

After a year off, Raymond returned to the Expos as an analyst, first on radio (1973-84) and then on television (1985-2001). During these years he also offered baseball clinics in all corners of Quebec. Thousands of youngsters were given an opportunity to benefit from his knowledge. In February 2002, Omar Minaya, the general manager appointed by Major League Baseball to run the Expos, hired him as a coach.

On September 29, 2004, at the Expos’ last game in Montreal, Raymond represented the team and addressed its French-speaking fans for a final time. “I didn’t want to leave the stadium,” he said of that night, “I didn’t want to take off my uniform. I know how many young people have dreamed of wearing it. I even thought that I would wear it to bed.”[22]

“Claude Raymond is the very opposite of today’s spoiled stars,” wrote André Pratte, editor-in-chief of La Presse, “a modest man, unpretentious, hard-working. Raymond set out for the United States in 1955, at a time when Quebecers still didn’t believe they could compete among the best and become successful beyond the local parish. He wasn’t even 20 years old.

“Claude Raymond,” continued Pratte, “is a pioneer, an athlete of the highest order and above all a gentleman. He has been an outstanding ambassador for the Expos, for Montreal and for Quebec. Thank you, Mr. Raymond.”[23]

(Translation: William Young)

This article originally appeared in the book Go-Go To Glory–The 1959 Chicago White Sox (ACTA, 2009), edited by Don Zminda.

[1] Claude Raymond and Marcel Gaudette, Le troisième retrait (Montréal, 1973), 20.

[2] Ibid.

[3] “Baseball,” Montreal Star, August 23, 1869, 2

[4] Raymond and Gaudette, 21-22.

[5] Ibid, 24.

[6] Ibid, 30.

[7] Ibid, 37.

[8] Jim Shearon, Canada’s Baseball Legends (Kanata, 1994), 170.

[9] Raymond and Gaudette, 39.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid, 42.

[12] Ibid, 44.

[13] Robert Duguay, “On pouvait même faire nettoyer nos vêtements gratis!”, La Presse (1998/04/15.

[14] “La rencontre des grands, ” Le Nouvelliste, November 13, 2007.

[15] Richard Milo, “Le match des étoiles de Claude Raymond”, Presse Canadienne, November 7, 1992.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Raymond and Gaudette, 62.

[18] Ibid, 64.

[19] Jean-Paul Sarrault. Les Expos Cinq Ans Après (Montréal, 1974), 47

[20] Ibid.

[21] Shearon, 172

[22] André Pratte, “ Merci M. Raymond”, La Presse, October 1, 2004.

[23] Ibid.

Full Name

Jean Claude Marc Raymond

Born

May 7, 1937 at St. Jean, QC (CAN)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.