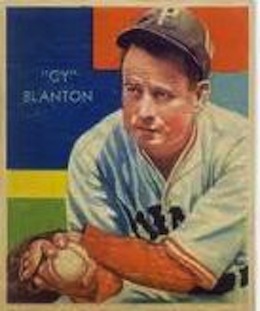

Cy Blanton

In 1935 Cy Blanton broke in with the Pittsburgh Pirates in a blaze of glory. The hard-throwing right-hander with an array of screwballs, curves, and sinkers led the National League in ERA and tied for the lead in shutouts, and was the hardest-to-hit pitcher in the big leagues. In his first four seasons he averaged 14 wins and 226 innings despite suffering from chronic elbow tenderness. Weeks after tossing an ill-fated no-hitter in a meaningless exhibition game in 1939, Blanton tore ligaments in his elbow, effectively ending his career. He won only 12 more games over the next four years as he battled injuries and the effects of alcoholism that led to his death in 1945 at the age of 37.

In 1935 Cy Blanton broke in with the Pittsburgh Pirates in a blaze of glory. The hard-throwing right-hander with an array of screwballs, curves, and sinkers led the National League in ERA and tied for the lead in shutouts, and was the hardest-to-hit pitcher in the big leagues. In his first four seasons he averaged 14 wins and 226 innings despite suffering from chronic elbow tenderness. Weeks after tossing an ill-fated no-hitter in a meaningless exhibition game in 1939, Blanton tore ligaments in his elbow, effectively ending his career. He won only 12 more games over the next four years as he battled injuries and the effects of alcoholism that led to his death in 1945 at the age of 37.

Darrell Elijah Blanton was born on July 6, 1908, to William and Mary Jane (Crow) Blanton in Waurika, Oklahoma. The Blantons were farmers in the small south-central Oklahoma town near the Texas border. Darrell, as he was known by family and friends, had three siblings and a half-brother from his father’s first marriage. By 1920 the Blanton family had relocated to Eastland, Texas, where William worked as a teamster in the booming oil business. Following a move to Fort Worth, Blanton attended North Side High School, where, according to the 1940 US Census, he completed only one year. Blanton’s introduction to baseball came from his father, a former semipro catcher. As legend has it, once his father recognized how hard his son could throw, he converted him from a catcher into a pitcher. Blanton honed his craft on the sandlots and semipro leagues of the greater Fort Worth area. In 1929 he supposedly hurled four no-hitters and once struck out 23 batters in a game for semipro Ellison.

The St. Louis Cardinals signed Blanton and assigned him to the Class C Shawnee (Oklahoma) Robins of the Western League in 1930. In his first season in Organized Baseball, the 21-year-old won 12 games and logged 222 innings, but struggled with his control, yielding 127 bases on balls. He also surrendered 146 runs (earned runs were not kept, which contributed to his league-high 16 losses. Around this time, Blanton acquired the sobriquet “Cy” for “no apparent reason”; however, it doesn’t tax the imagination that a young hurler nicknamed Cy was a reference to the most famous pitcher in baseball history.1

Assigned the following season to the Greensboro (North Carolina) Patriots in the Class C Piedmont League, Blanton labored through 57 innings (yielding 105 combined hits and walks, and 44 runs) before he was given his outright release in early June.2 He was signed by the Western Association’s Independence (Kansas) Producers (Class C), whose manager, Marty Purtell, had seen him pitch the previous season.

Blanton spent the next season and a half with Purtell and an organization which commenced an odyssey brought on by the economically unstable times of the Great Depression. After winning 12 of 20 decisions with the Producers in two-thirds of a season in 1931, Blanton developed into the league’s workhorse in 1932. He paced the circuit with 263 innings and 27 complete games; his 167 strikeouts ranked second and he tied for second with 18 wins. Blanton’s consistency was contrasted with that of his team, which relocated to Joplin, Missouri (and became the Miners), and moved again that season to Hutchinson, Kansas.

A turning point in Blanton’s career occurred in 1933. He had been acquired by the Tulsa Oilers (Class A Texas League) and was assigned to the St. Joseph (Missouri) Saints of the Western League. In his first season of Class A ball, Blanton set the circuit on fire with his record-breaking strikeout performances. On July 27 he whiffed 20 in a no-hitter versus Joplin. According to Frederick G. Lieb, the Pittsburgh Pirates had a “twist of luck” in their bid to sign the pitcher.3 They had a working agreement with Tulsa and had inquired whether early-season reports about Blanton’s strikeouts were accurate or a misprint. The team subsequently dispatched scout Carleton Molesworth to sign the 24-year-old.4 Blanton won a career-best 21 games and struck out 284 in 256 innings while walking just 97. He fanned ten or more 14 times, including twice in the postseason. “The way Cy Blanton went for St. Joseph,” wrote Porter Wittich, “looks bad on the extensive farm system of the Cardinals when they let him get away.”5

Blanton was invited to the Pirates spring training in Paso Robles, California, in 1934. The Sporting News reported that he “made a hit” with manager George Gibson with his speed and curves, but suffered from arm pain and poor control.6 He was kept on the Pirates roster until early May, when he was optioned to the Albany (New York) Senators in the International League. Injuries limited Blanton to only 147 innings at Albany, but he made his 26 appearances count. In three consecutive starts beginning on August 27, he struck out 10, an IL-record 20, and 18 batters; he also had three additional games with 13 strikeouts (no other pitcher in the league had registered more than 11). Blanton went 11-8 and led the IL with 165 strikeouts.

Some critics dismissed Blanton as a night-ball pitcher whose success was the result of pitching under the lights, still a novelty in 1933 and 1934. [The first night game in Organized Baseball was on May 2, 1930, in Des Moines; on May 24, 1935, at Crosley Field the Cincinnati Reds and Philadelphia Phillies played the first big-league night game.] “The fact that Pittsburgh bought me should be sufficient to disprove that claim,” said Blanton.7 The Pirates would not play under lights at Forbes Field until June 4, 1940.

The Pirates recalled Blanton after Albany’s loss in the IL playoffs. On September 23 at Forbes Field, he tossed five-hit ball over eight innings against the Chicago Cubs in his debut. He also yielded three runs and was collared with the 3-2 loss. Blanton joined the Pirates in a period of transition after their beloved owner Barney Dreyfuss died in 1932. Under Dreyfuss’s aegis, Pittsburgh regularly finished in the first division and often challenged for the pennant, winning in 1925 and 1927. William Benswanger, who had married Dreyfuss’s daughter, Eleanor, took control of the team as president in 1932; however, he never duplicated the team’s success of the 1920s.

Nationally syndicated sportswriter Harry Grayson considered Blanton a “question mark” for 1935.8 The Pirates were coming off their second losing season in the last four years, and wildly popular third baseman Pie Traynor, who had replaced Gibson in midseason as player-manager, did little to suggest that 1935 would prove more successful.

Blanton made a “sensational” splash in 1935 by tossing a one-hit shutout against the St. Louis Cardinals in his season debut on April 19. In his next start, he registered a career-best 11 strikeouts in a complete-game, six-hit victory against the Cincinnati Reds, 5-2.9 At 5-feet-11 and 180 pounds (20 pounds heavier than a year earlier), the right-hander cut an impressive presence on the mound with his steely blue-gray eyes, short, wavy red hair, and broad, muscular shoulders. Blanton completed his first nine starts, winning seven of them, and posted a 1.00 ERA in 81 innings through May 26 while the Pirates struggled to play .500 ball. Supremely confident, Blanton wasn’t surprised by his success. “When a player is shunted around as frequently as I was, he doesn’t have a great opportunity to find himself,” he said, and credited Traynor with the chance to pitch regularly, often on three days’ rest.10 Blanton found a kindred spirit (on and off the field) in a grizzled veteran, pitcher Guy Bush, whom the Pirates had acquired in a trade from the Cubs in the offseason. “Whatever I’ve accomplished this year,” said Blanton about his roommate, “has been through the efforts of Guy Bush.”11

A tough-as-nails competitor, Blanton was stricken with a severe case of appendicitis and was hospitalized in mid-June. He missed two weeks of action and was ineffective for another two weeks, before regaining his strength by the end of July. He completed 10 of his final 13 starts en route to an 18-13 record and became the first rookie to lead the NL in ERA (2.58). Surrendering a big-league-low 7.8 hits per nine innings, Blanton tied for the NL lead in shutouts (4) and set career highs in innings (254?) and complete games (23) for the fourth-place Pirates.

Gifted with “dazzling speed,” Blanton’s success resulted from his breaking balls – especially a screwball and a “downer.”12 He was often compared to baseball’s most famous screwballer, Carl Hubbell. The two pitchers were both from Oklahoma and good friends. They barnstormed together (along with a set of famous brothers from the state, Lloyd and Paul Waner) after the 1934 season, and spent hours together talking baseball and the art of pitching. According to The Sporting News, Blanton “perfected a delivery similar to Carl Hubbell, ball fading away in such fashion that even experienced batters find (the) greatest difficulty in contacting it.”13 He threw two types of screwballs and rotated his elbow and wrist differently so that one broke away from left-handed batters and the other broke away from right-handed batters. Blanton’s downer (also called a drop ball or a dew drop, and even a sinker) was a knee-bucking overhand curveball. One contemporary report described it as like a screwball, but one that broke straight down and often hit the dirt in front of home plate. “Some batters have compared it to the dip in a roller coaster. It takes an upward swing and drops to the bottom with such breath-taking speed that it is in the catcher’s glove before you know it,” read a contemporary report.14

Blanton was widely tabbed as a 20-game winner for 1936. Pirates beat reporter Ralph Davis wrote that he “would have proved even more of a sensation [in 1935] had he had a classy backstop to work with.”15 The team’s primary catcher, Tom Padden, led the NL in errors and stolen bases allowed even though he started just 90 games. The Pirates acquired Al Todd from the Philadelphia Phillies in the offseason, though a midseason injury forced him out of action for six weeks beginning in mid-July.

Blanton struggled out the gate in 1936, failing to pitch more than four innings in his first four starts, and was shunted to the bullpen to work on his control. He is “utterly unable to strike the stride which made him the sensation of 1935,” opined Davis.16 In stark contrast to his rookie season, Blanton ended the month of May with an ERA well north of 6.00, only one win (in relief), and no complete games. He finally got on track in June and once again staked his claim as one of the best pitchers in the NL. From June 8 through the rest of the season, he posted a stellar 2.56 ERA (second only to Hubbell) in 175? innings while completing 15 of 22 starts. While the Pirates duplicated their fourth-place finish, Blanton paced the circuit with four shutouts and finished with a misleading 13-15 record.

Blanton’s variety of breaking pitches caused havoc for batters and umpires alike. He ranked third in the NL in 1935 and 1936 in strikeouts per nine innings (trailing only Van Lingle Mungo of the Brooklyn Dodgers and the St. Louis Cardinals’ Dizzy Dean) and surrendered only 12 home runs in 490 innings. “[Blanton] is the hardest pitcher in the league for an umpire to handle,” said veteran NL umpire Dolly Stark. “He has to be on his toes every minute. Almost every ball he throws has something on it. … The deliveries vary so much that you have to have eagle eyes to tell whether the pitch is breaking over the corner at the legal height or below the knees.”17

Manager Traynor hired coach Johnny Gooch to work with the “problem child” Blanton and other Bucs hurlers in 1937.18 Gooch, a former catcher on the Pirates pennant-winning teams of the 1920s, had a reputation as an excellent handler of pitchers. The strategy paid immediate dividends. Blanton tossed a five-hit shutout against the Chicago Cubs on Opening Day, at Wrigley Field. The performance, described by Bucs beat reporter Charles J. Doyle as “the smartest in Blanton’s kaleidoscope career,” gave the team hope that the right-hander would repeat his heroics from 1935. Through June Blanton was one of the hottest pitchers in the league: He hurled nine complete game victories, including four shutouts, and owned a 2.02 ERA. But the right-hander’s ERA more than doubled over the last three months of the season, and he had trouble going deep in games, giving rise to reports that he was fighting arm pain. The mainstay of an injury-prone staff, Blanton tied for the NL lead in starts (34), and led the Pirates in wins (14), innings (242?), complete games (14), and shutouts (4).

In 1937 Blanton was named to his first All-Star team, joining teammates and starters Paul Waner (RF) and Arky Vaughan (3B). With two outs in the fourth inning, Blanton replaced Hubbell, who had been scorched for three runs in two-thirds of an inning. He struck out Joe DiMaggio, the only batter he faced, in the NL’s 8-3 loss.

In 1938 arm pain limited Blanton to only nine starts and periods of inactivity through June while the Pirates seemed destined for another middle-of-the-pack finish. But the Pirates and Blanton got hot at the same time. While Blanton won a career-best eight consecutive decisions from June 19 through August 3, the Bucs commenced a 13-game winning streak on June 29. Blanton and reliever Joe Bowman notched wins as Pittsburgh swept a doubleheader from the Boston Bees on August 3 to move a season-high 26 games over .500 and maintain a 5½-game lead in the pennant race. But lacking pitching depth and an ace, the Pirates won only 27 of their final 58 games; Blanton went 2-8 and was an afterthought down the stretch when the team needed a stopper. The Pirates lost the pennant in the final week of the season as the Cubs came roaring back in the fateful month. On September 28 Gabby Hartnett hit one of the most famous walk-off home runs in baseball lore, “the Homer in the Gloamin’,” to defeat the Pirates, 6-5, at Wrigley Field and give the Cubs a half-game lead. It was another 20 years before the Pirates finished in second place, and two more after that before they were serious pennant contenders.

Ranking among the most dubious decisions in big-league history, Traynor permitted Blanton, coming off an injury-riddled season, to pitch a nine-inning no-hitter in a pointless exhibition game against the Cleveland Indians in New Orleans on Easter Sunday 1939, just days before the regular season. Blanton subsequently tore ligaments in his elbow in his third start of the season, effectively ruining his career. “I had intended to allow Blanton to go about six or seven innings,” Traynor told Pittsburgh sportswriter Les Biederman in 1948. “I never saw Cy look as good as he did that spring. I hoped the Indians would get a hit and break the spell. … I couldn’t take him out of the game with a no-hitter coming up.”19 Blanton made an abbreviated return in August. In his last appearance in a Pirates uniform, he was rocked for seven hits and four runs in four innings against the Reds on September 7. The Pirates cleaned house after their worst season since 1916. Traynor, who had seemingly lost his clubhouse after the team’s collapse a year earlier, was replaced with the combative Frankie Frisch; and by the end of the calendar year, Blanton was sold outsight to the Syracuse Chiefs of the International League.

Sportswriters were quick to assess the reasons for Blanton’s injury and failure to live up to the promise his rookie season suggested. Charles J. Doyle believed that Blanton “throws in an unnatural manner, the tendons of the elbow paying a stiff price.”20 Chester Smith, the sports editor at the Pittsburgh Press, wrote that Blanton had “one of the best curves any young pitcher ever owned” and his down-ball was a “nightmare for catchers and a distinct pain in the neck for batters”; however, he should have occasionally altered his motion and delivery. Smith reported that according to rival managers, Blanton lost his effectiveness because “the batters got to know just where Cy’s hook was going to break, so they learned to time their swing,”21

Syracuse was disappointed with Blanton even before he threw his first pitch for them. The enigmatic hurler claimed he was “sold down the river” and threatened to hold out.22 Following losses in Blanton’s only three appearances, the Chiefs tried to return him to Pittsburgh, arguing that he was not worth the $10,000 they paid for him. When the Pirates rebuffed such claims, Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis called for a hearing and subsequently declared Blanton a free agent, on May 21.

In need of a job, Blanton worked out for the Philadelphia Phillies at Shibe Park. Manager Doc Prothro, whose club had lost 106 games the previous year, was impressed enough to sign the beleaguered hurler. Blanton was shelled for 12 earned runs in 8? innings in his first three appearances (all in relief) with the club; however, the Phillies needed arms, and Blanton was moved to the starting rotation. He exacted revenge against the Pirates by defeating them, 4-2, on June 26 in Philadelphia, to notch his first win in ten months. It was the first of three consecutive complete-game victories, which The Sporting News described as a “mild sensation.”23 The feel-good story of midsummer turned sour when Blanton blew out his elbow on August 2, ending his season and once again casting doubts on his future.

Not only did Blanton recover, he was named the starter for Opening Day in 1941. He held the Boston Braves hitless through six innings before yielding five runs (only two earned) in a complete-game, four-hit victory, 6-5. Phillies beat reporter Stan Baumgartner spared no hyperbole in his praise of Blanton: “[He’s] hurling with the guile of a (Christy) Mathewson . . . [and has] tied opposing hitters in knots.”24 On June 7 Blanton tossed the last of his 14 big-league shutouts by holding the Pirates to eight hits and improving his record to 5-1. Surprisingly, he was named to the All-Star team (the only member of the lowly Phillies), but did not pitch. Blanton went a dismal 1-12 after his hot start; however, the Phillies, one of the most awful teams in big-league-history (43-111) scored two runs or less in eight of those losses. Twice Blanton hurled ten-inning complete-games, yet saw them ruined by the league’s lowest-scoring team and porous defense (tied with the Pirates for worst). Blanton’s 4.51 ERA (in 163? innings) was just a sliver above the staff’s mark (4.50) which was the league’s highest for the sixth consecutive season.

Blanton gained national attention near the end of the baseball season when Life magazine published an article boldly claiming that curveballs were optical illusions. The widely read weekly relied on pioneering photographer Gjon Mill, who had perfected a technique using high-speed and time-lapse photography enabling him to capture a sequence of events in one image. He shot Blanton and Carl Hubbell throwing and followed the ball’s arc. With such pictorial evidence, Life boldly claimed that “no pitcher, it seems, has a strong enough finger and wrist motion to put the necessary spin” to curve a ball.25

Physically deteriorated, Blanton was rushed to a hospital in Philadelphia in early May 1942 suffering from what physicians later diagnosed as a kidney abscess. He had been “practically useless” as a pitcher that season, losing all four of his decisions and logging just 22? innings.26 Hospitalized for more than a month, Blanton reportedly lost more than 30 pounds and underwent a kidney operation. The Phillies harbored no sentimental attachment to their hurler and released him outright on June 12.

Blanton convalesced in Shawnee, Oklahoma, which he had called home since his first year in Organized Baseball. He married Frances Maries Brown, a local girl, in 1931, and had two children, Marita Jane and Dexter.

Blanton’s final three years of life were tumultuous. He signed with the Philadelphia A’s in spring 1943, but was released in early May when he failed to report to the team.27 He subsequently signed with the unaffiliated Hollywood Stars of the Pacific Coast League, for whom he split his 18 decisions and led the team with a 2.70 ERA in 150 innings. A holdout the following season, Blanton finally reported to the team in late July, and logged only 68 innings. His abbreviated and confrontational tenure with the Stars came to a close the following spring when co-owner and president Victor Ford Collins suspended him for “failure to observe training rules,” a euphemism of the time referring to excessive drinking and carousing.28 One month earlier, Blanton had reported to the local draft board in Ontario, California, for an army physical, and the pitcher was summarily rejected as unfit for active duty.

Outfielder George Watkins once described Blanton’s pitches as a “ball with eyes – it keeps ducking away from bats.”29 But Blanton’s once-promising career was cut short by injuries and excess. In nine seasons in the big leagues, he posted a 68-71 record and a better-than average 3.55 ERA in 1,218? innings. He also won 90 games and logged more than 1,300 innings over nine seasons in the minors.

After his suspension Blanton returned to his hometown. On August 30 he was admitted to the Central Oklahoma State Hospital for the mentally ill in Norman. He died on September 13, 1945, at the age of 37. According to his death certificate, Blanton had suffered multiple internal hemorrhages caused by cirrhosis of the liver, and was diagnosed with toxic psychosis.30 He was buried in Tecumseh Cemetery.

Sources

Chicago Daily Tribune

New York Times

The Sporting News

Ancestry.com

BaseballLibrary.com

Baseball-Reference.com

Retrosheet.com

SABR.org

Cy Blanton player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, New York

Notes

1 Harry Grayson, “Cy Blanton’s Screwball Breezes National Hitters,” The News-Herald (Franklin, Pennsylvania), May 17, 1935, 12.

2 Associated Press, “Charlotte Castoff Pitches One Hit Gem,” Burlington (North Carolina) Daily Times, June 9, 1931, 6.

3 Frederick G. Lieb, The Pittsburgh Pirates (Carbondale, Illinois: Southern Illinois Press, 1948; reprint 2003), 255-256.

4 “Riff Raff,” Frederick (Maryland) News Post, October 2, 1933, 7.

5 Porter Wittich, “The Globe Trotter,” Joplin (Missouri) Globe, October 3, 1933, 6.

6 The Sporting News, March 22, 1934.

7 Harold K. George, “Bush League Strikeout Hurler Joins Pirate Staff,” San Bernardino (California) County Sun, March 15, 1934, 11.

8 Harry Grayson, “Second Year Is Toughest,” Lowell (Massachusetts) Sun, January 17, 1935, 17.

9 The Sporting News, May 2, 1935, 5.

10 The Sporting News, May 16, 1935, 3.

11 Ibid.

12 Associated Press, “Cy Blanton Is Albany’s Hope,” Daily Messenger (Canandaigua, New York), September 10, 1934, 7.

13 The Sporting News, August 9, 1934, 2.

14 “Blanton a Fixture Now,” Kansas City Star, December 25, 1935, 14.

15 The Sporting News, April 9, 1936, 2.

16 The Sporting News, May 28, 1936, 2.

17 “Cy Blanton’s Plate Cutting Hard On Umps,” Altoona (Pennsylvania) Tribune, March 6, 1936,8.

18 The Sporting News, April 29, 1937, 3.

19 Les Biederman, “Blanton’s Ill-Fated No-Hit Feat Recalled By Traynor,” Pittsburgh Press, April 4, 1949, 18.

20 The Sporting News, July 6, 1939, 2.

21 Chester L. Smith, “The Village Smithy,” Pittsburgh Press, December 26, 1939, 19.

22 Associated Press, “Blanton Threatens To Stay On Farm,” Altoona (Pennsylvania) Tribune, March 14, 1940, 7.

23 The Sporting News, August 8, 1940, 6.

24 The Sporting News, May 15, 1941, 3.

25 “Baseball’s Curve Ball. Are they Optical Illusions?” Life, September 15, 1941, 84-85.

26 The Sporting News, June 25, 1942, 2.

27 The Sporting News, April 22, 1943, 3.

28 The Sporting News, April 5, 1945, 15.

29 The Old Scout, “No Santa Claus For Cy Blanton,” (unattributed article), December 26, 1939. Blanton’s Hall of Fame file.

30 Standard Certificate Of Death, Cleveland County, Oklahoma. Blanton’s Hall of Fame file.

Full Name

Darrell Elijah Blanton

Born

July 6, 1908 at Waurika, OK (USA)

Died

September 13, 1945 at Norman, OK (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.