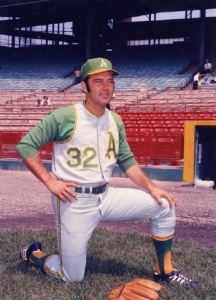

Darold Knowles

Darold Knowles, a left-handed reliever whose 16-year career spanned three decades, is best known for a World Series record that may be tied but will never be broken. He is the only pitcher to appear in all seven games of a World Series, accomplishing that feat with the 1973 Oakland A’s. Knowles did not yield a run in 6⅓ innings in that Series while bookending saves in Games One and Seven.

Darold Knowles, a left-handed reliever whose 16-year career spanned three decades, is best known for a World Series record that may be tied but will never be broken. He is the only pitcher to appear in all seven games of a World Series, accomplishing that feat with the 1973 Oakland A’s. Knowles did not yield a run in 6⅓ innings in that Series while bookending saves in Games One and Seven.

“It’s kind of my claim to fame,” said Knowles. “The amazing thing to me is that it’s been 40 years and no one else has ever done it.”1

A native of Brunswick, Missouri, a small community on the Missouri River in the north central part of the state, Knowles was born to Ralph and Verna Anne Knowles on December 9, 1941, two days after Pearl Harbor was attacked. Among his many jobs, Ralph drove a bus and worked for both Kansas City Power and Light and the Missouri Cities Water Company. He served in the military during World War II and took part in the postwar occupation of Japan. Darold’s only sibling, older brother Ralph Wayne, died one week prior to the author’s interview with Knowles.

“I knew from when I was in Little League that I wanted to be a baseball player, and my parents were very, very supportive,” he said. “They were not wealthy people at all, on the contrary; but I never missed a ballgame. Whatever they could do to get me there, they did.”

A standout amateur player, Knowles played for Moberly in the Central Missouri Ban Johnson League, where on July 16, 1959, he struck out 32 batters in a 13-inning, 1-0 victory over of Boonville, giving up only four hits and two walks.2

“That was a big night; I can remember like it was yesterday. Bunny Brummel was the opposing pitcher and he struck out I think 18, and I just had one of those nights. … Hell, I’ll always remember it. The scouts tried to sign me after that game and they didn’t even see me pitch; [they wanted to sign me just based on] the results of it. There was one scout there and eventually I wound up signing with him, a guy named Byron Humphrey with the Baltimore Orioles.”

Before signing, however, Knowles attended the University of Missouri at Columbia on a partial scholarship for one semester, but never played baseball for the school.

“Books and studies weren’t my big thing,” Knowles said. “I signed with the Baltimore Orioles for $5,000 and that was so much money that we spread (the payment) out over two years.”

Knowles became part of a talented Orioles minor-league system beginning in 1961 with Class C Aberdeen, where he went 11-5, starting 22 games in 23 appearances. By 1963 he had moved up to the Double-A Elmira Pioneers, a team that featured two other notable lefties in Steve Dalkowski and Pat Gillick. Knowles chuckled at the mere mention of the former.

“Even before I played with Dalkowski, he was a legend. When he came to Elmira, he had hurt his arm and he wasn’t throwing quite as good as he did at one time, but he had very good stuff. We used to get on him all the time, so much that we were talking about him throwing a ball through a fence and we went out to the right-field fence in Elmira. It was an old wooden fence and he did throw a ball right through it and I watched it. Steve said, ‘Aw, it was old.’ I didn’t see him when he could really throw, but he was in the 90s then when I played with him.”

Pat Gillick made quite an impression on Knowles as well. “I didn’t see Gillick for 25 years and I was with the Phillies as a coach and we were in spring training or the instructional league in Dunedin, where the Blue Jays train, and he was general manager of the Blue Jays. I walked up to him and said hello and he remembered the street I lived on in Missouri! He had that kind of mind.”

Gillick was famous among his Elmira teammates for reading The Sporting News and instantly remembering all that it contained. “We used to call him Sporting News. It obviously helped him in later life,” recalled Knowles.

The 6-foot, 180-pound lefty worked his way up the Baltimore organizational ladder and made his debut on April 18, 1965, against the Red Sox in Boston. “I remember it very well. I was pumped about being in the big leagues obviously, and here I am at Fenway Park and I faced Félix Mantilla and struck him out on a 3-and-2 curveball looking. Had no business throwing a curveball 3-and-2 but I did and I happened to throw it over and he took it. And I did not record another out that day.” Knowles actually pitched 1⅓ innings in his debut, but it may seem to him now as if he never retired another hitter, as he walked three and hit a batter while yielding two hits and four runs.

The lefty pitched in only four more games for Baltimore that year, spending most of the season in Triple-A Rochester. After the season he was traded with outfielder Jackie Brandt to the Philadelphia Phillies for pitcher Jack Baldschun. (The Orioles immediately included Baldschun as part of a package for Cincinnati’s Frank Robinson.)

Appearing in 69 games for the Phillies in 1966, Knowles notched 13 saves, but was again traded during the offseason, this time to the Washington Senators for outfielder Don Lock. Being traded two consecutive years did not rattle his confidence, he said.

“Trades are just a part of the game. I was happy to still be playing. I liked Philly. It was my first full year in the big leagues. Gene Mauch was the manager and gave me a chance to really prove that I could pitch so I’ll always thank him for that, but at the end of the year he kind of got down on me. I finished very slowly and did not pitch well the last month of the season. Later on I found out that’s why he traded me, because he just didn’t think I was going to be strong enough to pitch that much, I guess.”

Knowles established himself in Washington, never recording an earned-run average above 2.70 in his four full campaigns there. His 1968 season was interrupted when his Air National Guard unit was activated and sent to Japan.

“I went overseas in July of ’68 … but I was still on the active roster of the Senators up until the time I went overseas. I think I pitched in 20-some ballgames before I went over there, but it was an exhausting period because I’d go to the military base all day and then have to go to the ballgames at night.”3

Back from the service in 1969, Knowles was named to the American League team for the All-Star Game and pitched two-thirds of an inning of hitless relief.

“I really pitched well that year. I came back from overseas and missed the first month of the season and still made the All-Star team so I was really throwing the ball extremely well, and it just all came together for me in a short period of time. I was thrilled to even pitch in that game. We got beat pretty bad … but I think Frank Howard hit two home runs that day. I faced two hitters and got ’em both out, so I was pumped!”4

Knowles’ 1970 season is proof that a pitcher’s won-loss record is not necessarily indicative of how well he pitched. Despite 27 saves and a 2.04 ERA in 119⅓ innings, the southpaw recorded only two victories against 14 defeats.

“I felt and still feel that [1970] was probably one of the best years I ever had. I pitched well, I thought, but the results did not turn out real well sometimes. But I remember Ted Williams [Washington’s manager] coming to me early in the season and saying, ‘Every time we get to the seventh inning and we’re tied or winning I’m going to give you the ball.’ And he did. If we had a lead everything was fine, but it seemed like if we were tied, somebody would make an error or I’d give up a run and I wound up losing. It was a long, long year that way.”

It was such a long year for Knowles that even his hotel-room assignment seemed to conspire against him one night in Milwaukee.

“I was 2-12; I’d just lost my 12th game [versus the White Sox, 4-3, on a Rich Morales sacrifice fly in the ninth]. We went to Milwaukee after the game and I walked up to my room and it was number 212. I thought, that’s really great.”

On May 8, 1971, Knowles and first baseman Mike Epstein were traded to Oakland, a move that initially disappointed Knowles.

“When I first got traded I was kind of down. I loved Washington; had a home there and even though we were a last-place club, I was the main cog out of that bullpen. I was the big guy, I was the closer, and I loved that. I went to Oakland and they had this other guy named Fingers, a guy with a mustache,” Knowles said with a laugh. “It wasn’t long, maybe ten days, two weeks, and all of a sudden I said, ‘We can win it all here.’ Rollie was the horse, there’s no question, but we complemented each other pretty well. Either he got the save or I got the save, it seemed like. If he’d get 30, I’d get 12.”

“When I first got traded I was kind of down. I loved Washington; had a home there and even though we were a last-place club, I was the main cog out of that bullpen. I was the big guy, I was the closer, and I loved that. I went to Oakland and they had this other guy named Fingers, a guy with a mustache,” Knowles said with a laugh. “It wasn’t long, maybe ten days, two weeks, and all of a sudden I said, ‘We can win it all here.’ Rollie was the horse, there’s no question, but we complemented each other pretty well. Either he got the save or I got the save, it seemed like. If he’d get 30, I’d get 12.”

Knowles appeared in 43 games for the A’s during the regular season, winning five and notching seven saves. He made his first postseason appearance with one-third of an inning in Oakland’s loss to the Orioles in the American League Championship Series.

Going 5-1 with a career-low 1.37 ERA in 1972, Knowles helped the A’s to the pennant but missed the postseason, including the A’s World Series triumph over Cincinnati, after he broke a thumb on September 27 against Minnesota. Batting against Bert Blyleven in the bottom of the tenth with Dick Green on first, Knowles hit a ball that he thought might fall in for a hit.

“It had rained the night before, which was a rarity in Oakland, and the field was not in great shape. Anyway, I hit a ball and I thought when I hit it that it had a chance to be a double. I rushed out of the box and slipped and I jammed my thumb into the ground and broke it. The guy [César Tovar] caught the ball anyway. That was a low point in my life because if you play this game you want to get in the World Series; you want to perform in the World Series, but I missed it all. I was there, but I didn’t have an opportunity to pitch.”

Knowles more than made up for that lost opportunity in the 1973 World Series. He recorded nine saves in 99 innings that season but never made it into any of the ALCS games against Detroit. “It seemed like I was up throwing in every game [in the playoffs], but I didn’t have to go in, but that was okay; it was all about the team.”

In Game One of the World Series, however, with the A’s clinging to a 2-1 lead over the New York Mets, Knowles came in with one on and one out in the ninth to relieve Rollie Fingers, who had pitched 3⅓ innings in relief of starter Ken Holtzman. Fingers had walked pinch-hitter Ron Hodges. Knowles retired pinch-hitter Jim Beauchamp on a pop fly to second baseman Dick Green and then got third baseman Wayne Garrett on a short fly to right fielder Reggie Jackson.

New York, with an 82-79 regular-season record, seemed no match for the powerful Oakland squad, but the Mets battled tenaciously and the Series came down to a deciding seventh game.

“When that Series started, my dream was to at least pitch in one game. As luck would have it, I relieved in the first game and got the save, so now I had pitched in a World Series game and I was pumped. And then I got in the second one and the third, fourth, and so on and nobody even knew; it wasn’t even mentioned that no one had ever pitched in all seven games until that morning. I read it in the paper that if by chance I got in that game, I’d be the only one to do it.”

It appeared that Knowles would not pitch in the seventh game and that Rollie Fingers would record his third save of the Series, but Fingers gave up a walk and a single in the ninth with the Athletics leading 5-1. With two down, first baseman Gene Tenace booted a groundball, allowing a run to score and bringing the tying run to the plate in the person of the left-handed-hitting Wayne Garrett, the same hitter Knowles had retired for the save in Game One. Manager Dick Williams brought in Knowles.

“I always thank Gino for that [error]! As far as Dick taking Fingers out; Fingers had already thrown two-plus innings in that game. Wayne Garrett was the hitter and that was kind of my thing, being able to get left-handed hitters out. [Williams] played it by the book and brought me in and I was lucky enough to get the out. That was the biggest thrill I ever had in baseball, getting that last out.”

Indeed, Fingers had hurled 3⅓ innings in that final contest and 13⅔ for the Series. To put that total in perspective, starter Ken Holtzman amassed only 10⅔ innings in three games started.

Knowles laughed about relieving the future Hall of Famer with the World Series on the line. “I give Dick Williams a lot of credit — that took some [guts] to take Fingers out of the game and bring me in.”

The Athletics again won the AL West in 1974 and again Knowles did not appear in the ALCS against Baltimore. He never saw action in a World Series game either. Rollie Fingers was named Most Valuable Player in Oakland’s thrashing of the Los Angeles Dodgers in five games, winning the first game and saving the fourth and fifth. The only other relief pitcher to see action for Oakland was Blue Moon Odom, who pitched 1⅓ innings in two appearances. According to Knowles, there may have also been another reason that he did not appear.

“I wasn’t in Alvin Dark’s good graces in ’74 (Williams had resigned as manager after the 1973 season), to be honest and I didn’t have a great year.5 I can see why he got down on me a little bit. It seemed like I was up throwing in every game, I just didn’t get in any of them.”

Reflecting on those championship teams Knowles acknowledged that Oakland’s reputation as “the fightin’ A’s” was well deserved. “Everything you read or heard about the Oakland As, the bickering the fighting (and all of it wasn’t in the paper), it’s probably all true, but I can honestly say this: When the game started everybody was a true professional. There was never anything carried over that would cost anything as far as the game was concerned. But yeah, there were a lot of ego differences, if you will, in that clubhouse and it was just part of it. Every day you’d wait to see what was going to happen and usually, it did! There was always something going on.

“I played for eight different major-league clubs and that is the only club that I played for that ever had anything like that. You put that many guys together for that long a time, there’s some bickering and maybe a spat or two, but they weren’t spats in Oakland, I mean there were some fisticuffs, and that was going on all the time. There were some pretty good [fights]. But it never prevented anybody from playing the game.”

Shortly after the 1974 World Series, Knowles was traded to the Chicago Cubs along with pitcher Bob Locker and infielder Manny Trillo for outfielder Billy Williams. Two years in Chicago were followed by a year in Texas and then a year in Montreal, where Knowles recorded six saves, a 3-3 record, and a 2.38 ERA.

“I had a good year in Montreal and they wanted me to come back. They offered me a contract with a nice raise, but I just didn’t like playing in Montreal. My kids were small, it was a French-speaking province, and my family didn’t enjoy it. [It was a] good ballclub, but I thought, ‘I got a chance to play out my option and become a free agent,’ and I did. I took the chance and I wound up with the Cardinals which is where I always wanted to be my entire career, having grown up in Missouri. Unfortunately, it was at the tail-end of my career and I didn’t have that much left. I didn’t have the good stuff that I had earlier, but it was okay — I wound up playing for my boyhood dream team and loved every minute in St. Louis. And then went to work for them when I got out of the game.”

Knowles’ last appearance in the big leagues occurred on the 16th anniversary of his major-league debut. It was April 18, 1980, in Pittsburgh. In two-thirds of an inning, the left-hander surrendered two runs on three hits and took the loss in the Cardinals’ 12-10 defeat.

Knowles was a roving minor-league pitching coach in the Cardinals’ system from 1981 to 1988, a term that was punctuated by a six-week stint with St. Louis in 1983 when he filled in for Hub Kittle on the big club, whose wife was seriously ill. Knowles thoroughly enjoyed his time at Whitey Herzog’s side during that month and a half.

“This is how good a manager Whitey Herzog is. We are in LA — I’ll never forget this — it’s in the sixth inning and I think Bob Forsch was on the mound and there’s two out and nobody on. Somebody got a base hit up the middle and Whitey was just beside himself and I was standing there by him as the pitching coach and I said, ‘That’s all right, we got two out, Whitey.’ And he said, ‘Nah, now that damn Baker can beat us in the ninth.’ Dusty Baker hit a three-run homer in the ninth to beat us. I sat in the dugout for 20 minutes after the game thinking, ‘How in the hell did he think of that three innings in advance?’ And that’s exactly what he said, ‘Nah, that damn Baker can beat us now,’ and he did.”

Whitey Herzog was not the only legendary manager for whom Darold Knowles coached or played. “I was fortunate enough to play for some really good managers. Gene Mauch gave me my first full chance in the big leagues and I’ll always appreciate that. Then I went to Washington and played for Gil Hodges the first year. He was a great manager as well; he handled pitchers as well as anybody I ever played for. … Let me just say this about Ted Williams: Ted Williams, when he came, was probably the worst manager I played for during those years, but he got a lot better because he was such a perfectionist. He thought he knew a lot about pitching and he didn’t, but he was the most charismatic man I ever met in my life. I couldn’t wait to get to the ballpark every day and just listen to him. Everybody would sit around and talk and he loved that. I’ll never forget those days.”

Knowles had high praise for Dick Williams. “Dick Williams demanded — demanded — that those guys play the game with respect when they played. I think that was one of his biggest attributes. He demanded that from you. It’s probably one of the reasons it seemed like he had better results with a veteran club than he did with a young club because veteran players knew how to play and he made sure that they did that.”

Knowles left the Cardinals organization in 1989 when Lee Thomas, who had been the farm director in St. Louis, was named general manager of the Phillies and asked him to become the pitching coach. After two seasons with the big club, Knowles was reassigned (“That’s what they called it back then — ‘reassigned’”) to the Phillies’ Florida State League affiliate in Clearwater, where he spent ten seasons. From 2002 to 2005, Knowles was Pittsburgh’s Triple-A pitching coach, but when the Pirates asked him to coach rookie ball, he left and signed with Toronto. Knowles was assigned to Dunedin in the Florida State League, which was a boon to the lefty because it was his home.

Knowles was to enter his ninth season as Dunedin’s pitching coach in 2014. He still threw batting practice every day at the age of 72, but he wasn’t not dropping in any curveballs as he did to Felix Mantilla at age 23.

“I didn’t throw that curveball the last ten years I played. In the minor leagues I did throw it. Hell, I thought it was good, but it wasn’t that good. The last one I threw in the big leagues, Chuck Hinton hit off the wall. I finally went straight to the slider.

“I’m probably one of the luckiest guys in the game. I work in baseball. I enjoy working with the kids —I know that’s an oft-used saying, but it’s so true —and I’m home every night. That’s even better. I’m very fortunate.”

As a result of his lengthy coaching career with both Clearwater and Dunedin, Knowles was inducted into the Florida State League Hall of Fame in 2011. In 2012 Knowles was inducted into the Missouri Sports Hall of Fame — “both tremendous honors,” he said.

Knowles married three times. He had two daughters, Holly and Lori, by his first marriage; a third, Kali, by his second marriage; and a stepdaughter, Jamie, now deceased, by his third wife, Lynne.

In 2014 Knowles said he had no plans to retire from baseball any time soon. “It’s all I’ve ever done. I’m sure I’ve made a lot of mistakes, but I’d like to think I’ve helped a hell of a lot of people, too. And I enjoy it! I love it!”

Last revised: March 10, 2021 (ghw)

Notes

1 All quotes are taken from a January 7, 2014, phone conversation with Darold Knowles.

2 “Pitchers in a Battle,” Kansas City Star, July 17, 1959, 33.

3 Knowles pitched 41⅓ innings in 32 games with an ERA of 2.18.

4 The AL lost, 9-3. Frank Howard hit a home run off Steve Carlton in his only plate appearance. Knowles retired Matty Alou and Don Kessinger to close out the third inning.

5 Knowles amassed only three saves along with a 4.22 ERA in 53⅓ innings.

Full Name

Darold Duane Knowles

Born

December 9, 1941 at Brunswick, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.