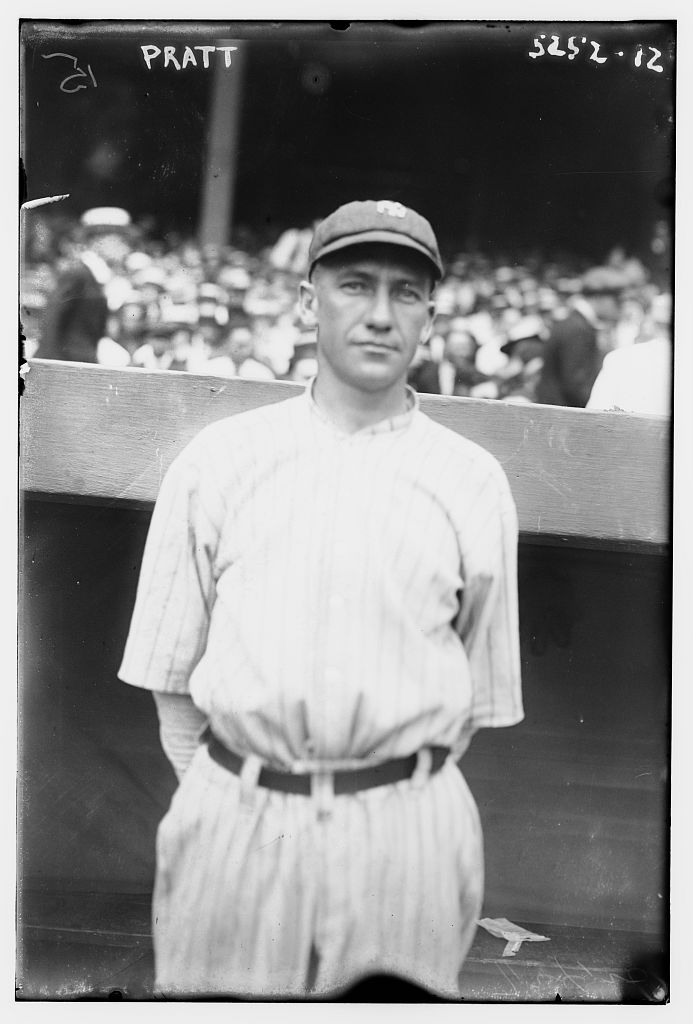

Del Pratt

Del Pratt was arguably the second-best second baseman of the second decade of the 20th century. And his argumentative nature led The New York Times’ John Kieran to call him “the greatest clubhouse lawyer baseball ever knew.”

Del Pratt was arguably the second-best second baseman of the second decade of the 20th century. And his argumentative nature led The New York Times’ John Kieran to call him “the greatest clubhouse lawyer baseball ever knew.”

Pratt was born into a well-off family on January 10, 1888, in Walhalla, South Carolina, near the Georgia-North Carolina border. His father, George Walker, was an industrialist in the cotton business. His mother, Mary Dawson Pratt, was a homemaker. In 1902, the family moved to Pell City, Alabama, near Birmingham, where George managed the Pell City Manufacturing Company, a cotton mill. In 1908, they moved to Tuscaloosa, where George Sr. became a cotton broker.

Del was wild about baseball at a very early age. His son, Donald, recalled that Mary always knew where to find her boy — on the sandlots. Del had the means to attend college, a rarity in those days. He started at Alabama Polytech (now Auburn University) and soon transferred to the University of Alabama, where he studied textile engineering. He earned varsity letters in both baseball and football in 1908 and 1909 for the “Thin Red Line” (the team’s nickname before the “Crimson Tide,” from a phrase in a Kipling poem). Del played shortstop and was team captain both years, including the Southern Intercollegiate Athletic Association champions of 1909, with a 19-3 record. Del was elected to the Alabama Sports Hall of Fame in 1972, along with Satchel Paige and (posthumously) Heinie Manush.

Del’s father took pride in his son’s athletic career, though he had initially opposed the idea of a baseball career. It was often reported during Pratt’s major league days that he didn’t need baseball for the money since his family was comfortable. In the early 1910s, he worked with his father in the brokerage business in Birmingham during the off-seasons.

After graduating from Alabama in 1909, where Pratt studied law (but did not get a law degree), he entered professional baseball in 1910 with a Class A club, Montgomery (Alabama) of the Southern Association. He injured a shoulder tendon “throwing out his arm” on a ball hit by Frank Chance in an exhibition game and missed a month. He hit only .232 and was sent to Hattiesburg (Mississippi) of the Class D Cotton States League that same year. His .367 average in 20 games brought him back to Montgomery in 1911. Not only did Del continue his solid hitting — .316 in 139 games — but he also showed his speed with 36 stolen bases. He led the league in batting average, hits, and runs. He still found time to stay connected to football, coaching Southern University in Greensboro, in 1910. It was the first of more than a dozen years in a row that Pratt would coach college athletics in the off-season.

The St. Louis Browns acquired Pratt for players and cash, along with a $250 signing bonus. He caught their eye during that 1911 season, and they recalled him under an option agreement at the end of that season. Early in 1912, John McGraw of the New York Giants offered St. Louis $8,000 for him, to no avail. The 1912 Browns’ spring training was at Del’s old stomping grounds, in Montgomery. He then embarked on a remarkable performance of consistency and durability in his first five years in the bigs:

- Averaged 156 games a year, leading the league in games four of the five years

- Averaged 31 steals a year

- Hit between .283 and .302 four of the five years

- Got between 159 and 175 hits a year

- Hit 26-35 doubles and 10-15 triples a year

- Averaged 80 runs batted in and almost 70 runs a year, during the low-offense Deadball Era

- Played in 360 consecutive games from late 1914 until early 1917

Had Del not been tossed from a game on September 2, 1914, by umpire Bill Dinneen, causing him to miss the second game of a doubleheader, his streak would have exceeded 700 games. That was the only game he missed from 1913 to 1916.

Pratt had a sparkling rookie season: a .302 batting average with 26 doubles, 15 triples, and a .426 slugging average. He accomplished all this on very weak teams. Only in 1916 did the Browns have a winning record. That was the first full season of another Brownie and former college star, the University of Michigan’s George Sisler. In 1915, the two former college men were roommates on the road.

Pratt also showed surprising power in his rookie season with five home runs (a significant number in the Deadball Era), including the first ever in Detroit’s new stadium, Navin Field. A year later, he ended Walter Johnson’s scoreless inning streak at 55⅔, by driving in a run with a single.

Del was a solid fellow, standing 5-foot-11 and weighing 175 pounds. He gained a reputation as a terrific second baseman, even though he wasn’t known for his defense at first. In 1913, the Globe-Democrat wrote that he’d have to work on his fielding to become a star, and the Post-Dispatch said later that season that he was a “juggler,” not an infielder. Just a few years later, The Sporting News called him the best defensive second baseman in the game. Pratt wasn’t flashy and had an easygoing way of covering a lot of ground and getting to the ball.

The numbers reflected the maturation of his glove skills. Del had tremendous range, leading the American League in chances and putouts five times, and double plays and assists three times. In the `teens, from 1913 to 1919, his chances per game were more than those of Eddie Collins, often by a large margin.

“Not bashful…said his part” was the way his nephew James Pratt recalled him. Del was outspoken and known for his temper. When Dave Fultz was organizing the Players’ Fraternity, the rookie Pratt was the Browns’ team representative. A year later, during a Browns-Cardinals game in the October 1913 City Series, Del got into an argument with the umpire, arguing that a ball he hit was foul. Cardinal bench jockeys rode Del, suggesting he was revealing union secrets to ownership. The St. Louis Times wrote that their words would have provoked any “self-respecting man.” His manager Branch Rickey, who described Del as “a high-strung Southern gentleman,” said it was “the nastiest remark I ever heard.” Del punched the Cards’ Zinn Beck and was tossed from the game.

The story did not end there. This was the first game of a doubleheader. When Pratt took the field for the second game, Cardinals manager Miller Huggins argued strenuously that Del had been banished for the day, not simply the first game. (In the early decades of the 20th century, ejection was for the day, not simply the game.) When the umpires finally sided with the little skipper, there was such acrimony that the City Series ultimately was called off and ended in a 3-3 (in games) tie. Shortly thereafter, Del resigned from his position in the Players’ Union. It was an incident that he would not forget.

On September 1, 1914, Del married Leontine Mindora Ramsaur of Florida. She was only 17 at the time. A strikingly attractive and soft-spoken young lady, and a talented musician, she had swept Del off his feet during spring training earlier that year, when the Browns trained in St. Petersburg. The wedding was an impromptu and informal affair; the judge waived the five-day waiting period for a marriage license, and the bride’s friends learned of the ceremony by telegram. It took place in Boston, shortly after the Browns had dropped a doubleheader to the Red Sox. Branch Rickey attended, representing the Browns.

Del was quoted in the Boston Globe, explaining the rush: “I believed that I could play better ball if I were married. Leontine is an inspiration.” The Boston Journal noted that he played like a married man earlier that day, when he went 5 for 8 with 10 total bases.

They would have four children and numerous grandchildren. Leontine would pass away in 1963. The 1930 Texas census lists the four Pratt children: Derrill Jr., Nona, Madeline, and Donald. Del Jr. gave his father an exemption from serving in the armed forces during the World War I. Nona was named after her maternal grandmother, Nona Ramsaur, who was born in Missouri circa 1874.

In 1915, when Browns’ manager Branch Rickey made a recruiting trip, he put his young second baseman in charge of the team. Later that season the Post-Dispatch reported that Pratt would coach the Washington University football team. In 1916, when Del’s batting average dropped to .267, he led the league in runs batted in with 103.

In 1916, the Browns gained a new owner and a new manager. With the demise of the Federal League after the 1915 season, the owner of that league’s St. Louis Terriers was allowed to acquire the Browns from Robert Hedges. Owner Phil Ball installed his manager, Fielder Jones, as the Browns’ manager and moved Branch Rickey to the position of business manager. The astute Jones, who had managed the 1906 world champion Chicago White Sox, dubbed Del Pratt as one of the best natural hitters he had ever seen.

Years later Del recalled the challenges of hitting in the Deadball Era: “You could kick a cocoanut with your bare foot as far as you could hit one with a bat.” Observing the modern game in the 1960s, he said, “This upsurge in power hitting has taken a lot out of the thinking aspect of baseball, which was much more common in the old days.”

1917 was a difficult year for Pratt, as he was seriously hampered by injuries for the first time in his major league career. Early in the season, he broke a bone in his wrist and missed three weeks. A week later, he was sidelined with a bad knee. Then, after a September 4 loss to the league-leading Chicago White Sox, 13-6, cantankerous owner Phil Ball accused his players of “laying down” on the job. The week before, the Browns had dropped four of five games to these same White Sox (in Chicago; they were now playing in St. Louis), by a combined score of 36-13. Before that series, the Sox were leading the AL by only 3½ games.

Pratt, shortstop Johnny Lavan and outfielder Burt Shotton all took issue with the remarks. They were so upset that they refused to suit up for the next day’s game until they met with Ball. When the get-together occurred, the Browns’ owner backed down and offered to print a retraction. He explained his statement by saying that his friends were telling him that the players were “laying down.” The players did suit up, and the issue seemed to be resolved.

Was Ball suggesting that the players were “dogging it” as the end of the season approached? The Browns were 36½ games out of first place at the time. Or was he implying something more sinister? The White Sox were leading the AL by 6½ games at the time. “Damn lie,” Del would tell his friends and family. “I played 100% every day.” Fifty-five years after the incident, Alabama sportswriter Morris Frank wrote, “An athletic contest was a contest to Del whether it was in Detroit or Dime Box.”

In reality, Ball did not single out any guilty parties. Instead he told The Republic that only three players were giving manager Fielder Jones “their best:” George Sisler, Jimmy Austin, and Hank Severeid. The three players who responded so strongly were having poor years, hampered by injuries.

The feisty Pratt and Lavan soon each filed $50,000 libel lawsuits against Ball. Del suggested that he would call countless ballplayers as character witnesses to testify about his efforts on the ball field. The legal action came as a surprise to many, especially after Ball’s retraction, and The Sporting News referred to Del as the team’s “Trotsky.” As the season wound down, it was apparent that the two infielders would not wear Browns uniforms the following year. Ball did state that he would not trade the players — a move they both wanted — until they dropped their suits. A few months later, Lavan got his wish and was traded to the Washington Senators, along with Shotton. Branch Rickey would bring the two men back to St. Louis — to the Cardinals — a year later.

In late December 1926, Swede Risberg, one of the banned Chicago Black Sox, stunned the baseball world by charging that the Detroit Tigers had lost two 1917 doubleheaders to the White Sox on purpose, for which the Sox rewarded Tiger players with cash. The games in question were two doubleheaders in early September, in between the five Browns games in Chicago and their poor 13-6 loss to Chicago. The White Sox were in a fierce battle for the pennant with the defending champions, the Boston Red Sox. Ultimately, Commissioner Landis found the White Sox guilty of poor judgment, but not a fix, accepting the players’ explanation of the cash gifts — which they could not deny — as thank-yous to the Tigers for beating the Red Sox themselves recently.

An understanding of the “laying down” incident appears murky. A close review of the game accounts, the personalities, and the season reveals that there probably were no “thrown” games. However, it appears that a key piece of the puzzle is the third party of the triangle. Besides the owner and the players, there was the manager, Fielder Jones. A number of players were dissatisfied with his harsh and humorless ways. A brilliant tactician who had led the Chicago White Sox “Hitless Wonders” to victory in the 1906 World Series, he cared little for soothing his players’ feelings.

The Browns were a team ridden by factionalism at the time. They were a combination of the Federal League’s St. Louis Terriers (Phil Ball’s team, before he bought the Browns, managed by Jones) as well as the Browns. It was also split between Branch Rickey’s men and those of Jones. John B. Sheridan explained the difference this way: “Rickey coddles and babies his players. He has a penchant for young collegians. Jones likes hard-bitten, stern-seasoned players from the ironworks and the mills.”

Less than a year later, Jones would suddenly quit the Browns after a tough loss and never return to baseball. In a lengthy three-part series in The Sporting News, Sheridan examined Fielder Jones’ management style and reasons for his lack of success in St. Louis. He was prompted to write the columns — quite unfavorable to Jones — he said, as a response to Jones’ claim that the St. Louis press was responsible for the Browns’ lack of success. Sheridan noted that Jones would “ride” Del Pratt, “a boyish Southerner, extremely sensitive, but garrulous, though a self-bred gentleman of education and manners.”

During the 1917 “laying down” controversy, this complex field leader publicly defended his players and their efforts from Ball’s charges. Privately, however, he pressured new business manager Bob Quinn to dump the malcontents. Del was particularly unhappy with his manager, and that — along with injuries for the first time in his career — goes a long way toward explaining his performance in 1917. After the Browns traded Del away a few months later, he shared his feeling about Jones with The Sporting News. He spoke of the skipper’s lack of tact and the fact that many “disaffected players” remained on the Browns.

In late October 1917, the New York Yankees fired manager Wild Bill Donovan after a disappointing sixth-place finish. AL President Ban Johnson was still smarting over the league’s loss of the talented Branch Rickey to the National League. Rickey had not gotten along with his boss Phil Ball, and when the cross-town Cardinals offered Rickey the team’s presidency that spring, he had jumped at the opportunity.

Johnson saw a chance to get back at the NL and suggested that the Yankees hire the bright skipper of the Cardinals, Miller Huggins. He was ready for the move after having lost control of player personnel decisions to Rickey. The deal was done, and the new manager — a second baseman himself in his playing days — was familiar with Del Pratt. Huggins felt that Fritz Maisel and Joe Gedeon were not adequate Yankees second basemen. And so New York went after Del.

The deal stalled for a few weeks, for a couple of reasons. The Yankees wanted Del to settle his lawsuit first. They also felt the Browns were simply asking for too much in return. On January 22, 1918, the Browns sent Pratt and 42-year-old pitcher Eddie Plank to the Yankees for Maisel, Gedeon, Les Nunamaker, pitchers Nick Cullop and Urban Shocker, and $15,000 in cash. Whether the Browns were demanding even more is unlikely.

When Plank retired to his Gettysburg farm, many observers thought the Browns had gotten the better of the deal. Baseball Magazine’s W.A. Phelon wrote, “it looks like five pretty good men for one ageing [sic] infielder.” Yankees owner Jacob Ruppert admitted he “had to pay all out of reason” for Pratt, but he and Huggins desperately wanted Del, to strengthen the team’s middle infield. Urban Shocker went on to become one of the game’s top hurlers, and Gedeon matured into a fine second baseman. He led the AL in fielding percentage 1918 and 1919 and hit .292 in 1920 with 177 hits. He was then banished from baseball for his prior knowledge of the Black Sox plot.

But the Yankees didn’t do so poorly. On the diamond, they got a lot of production from Del Pratt. Miller Huggins told reporter Bozeman Bulger that Pratt was “the man who put the ball club on its feet.” He immediately brought legitimacy and confidence to one of baseball ’s best infields, the tongue-twisting Pipp, Pratt, Peck (Roger Peckinpaugh), and Baker. Besides his solid glovework, Del averaged .295 the next three seasons, with both extra-base hitting and speed on the base paths. He continued to show his durability: he played in all but one game in 1918-1919-1920.

Writers have noted that cartoonist-columnist Robert Ripley coined the phrase “Murderers’ Row” for this Yankee infield in 1919, a year before Babe Ruth came to New York. Actually, sportswriter Fred Lieb used the phrase a year earlier. “Murderers’ Row,” he called their infield, now that Pratt had joined it (he also included outfielder Ping Bodie), “the greatest collection of pitcher thumpers in baseball today.”

Then there was the Del Pratt off the diamond. First came his holdout in his first spring as a Yankee. During this time, the Globe-Democrat wrote that the University of Alabama had offered Del a contract to coach their football team. In his defense, it was reported that the Yankees had offered him the same $5,000 salary he had in St. Louis in 1917. He went public with his dispute before settling for more money, according to The New York Times. Del ’s version of events was slightly different: “The offer from Alabama would have paid me as much money as I was offered by the Yankees, but my love of baseball induced me to accept the terms that Huggins offered.”

The Alabama offer enabled Del to keep his options open. He expressed concern that he might be railroaded out of baseball over his dispute with Phil Ball. He even asked the Yankees to put a clause into his contract that they couldn’t waive him out of the league because of it.

In the meantime, the Pratt-Lavan lawsuits were moving forward. In late February, 1918, Ty Cobb gave his deposition on behalf of the two players. He stated that a player’s reputation would be damaged if he were accused by his manager of “laying down.” Cobb went on that such charges would make it harder for a player to find work. Pratt and Lavan were always honorable, he concluded.

The lawsuits were settled in late March 1918, with the intervention of both league President Ban Johnson and Senators owner-manager Clark Griffith. While some newspapers reported that the case was settled in the plaintiffs’ favor, they probably got far less than $50,000. (The Sun wrote that Del received $5,400.)

The Yankees improved to fourth place in Huggins’ first season at the helm, after holding onto first place in early July. Their problem was not the infield, but rather the forgettable outfield of Ping Bodie, Elmer Miller, and Frank Gilhooley. In the off-season, Del went to work in a steel mill in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. Other ballplayers who worked with him in the mill included Rogers Hornsby, Harry Covaleski, and Sam Agnew. When 1919 rolled around, he told The Sun he was considering retirement because of his good job at Bethlehem Steel. Del was one of the first and most vocal baseball players who used good jobs in war-related industries as leverage for a better baseball contract. Del eventually came to terms, when he met with Yankee scout Joe Kelley. The Pratts were still living in Bethlehem the following year, as shown in the 1920 census.

It is interesting to note that another Yankees infielder contemplated retirement around the same time, almost on an annual basis: Frank “Home Run” Baker. His motivation seemed to be his ambivalence about playing ball and his love of family and home. He did come around after his “holdout” of 1919, but sat out the entire 1920 season to care for his young daughters after the death of his wife.

The 1919 Yankees were in the pennant race well into the summer. Once again, they occupied first place in early July, and they remained within striking distance until early August. They finished in third place, only 7½ games behind the Chicago White (soon to be Black) Sox. This was the Yankees’ highest finish since 1910. Their pitching had been bolstered by the midseason acquisition of pitcher Carl Mays from the Boston Red Sox in exchange for pitchers Allan Russell and Bob McGraw and $40,000. There were some newspaper reports that Boston would get another player as part of the deal. On August 1, The World reported that Del Pratt would be that man. There never was another player sent to the Red Sox in that deal, nor was there any further explanation.

In late March of 1920, a controversy erupted in the Yankee clubhouse over the distribution of third place money among the team members. Del led the protesters’ charge and even suggested that the players would strike over the matter. John B. Sheridan of The Sporting News wrote, “It was the most contemptible thing I have ever known in baseball.” The Yankees had included their trainer, groundskeeper, and two secretaries in the distribution, along with pitchers Russell and McGraw. Del felt these people were undeserving and took his case to ownership. The Yankees’ owners gave back to the team two shares valued at $915.70 (out of their own pockets, apparently, since the money had already been handed out), but held their ground on the support people. Each Yankee therefore got an additional $37.45. (The World and The Sun had good coverage of the affair, in late March 1920.)

Press reports quickly surfaced that the Yankees were unhappy with Del and might trade him. In the next few days, the team lost infielders Aaron Ward and Chick Fewster to injuries, the latter to a near-fatal beaning by Brooklyn’s Jeff Pfeffer. With third baseman Frank Baker already sitting out for the season, Del was no longer on the trading block.

In 1920 the American League New York franchise’s high point in wins, with 95, but the Cleveland Indians were the team that won their first pennant, with 98 victories. The Yankees were in the race until the end of the season, occupying first place as late as mid-September. Del usually batted cleanup or fifth, right behind the newest Yankee, Babe Ruth. It was also Del Pratt’s finest season so far in his nine-year career: highs in batting, on-base, and slugging averages (.314, .372, .427), and highs in hits and doubles (180 and 37).

Del’s hitting style was unusual, yet it got results. John B. Sheridan described it this way: “Take Pratt. He is a notoriously unstylish, yet most viciously effective hitter. … He violates all the rules of good hitting … he hits the bad ball to any field. … Pratt, to my mind, is one of the most dangerous hitters I have ever seen. You can’t pitch to him.” Del’s 1918 Yankees teammate, pitcher Ray Caldwell, said, “He [Pratt] can hit anything he can reach, high, low, fast, or slow.”

On August 23, 1920 Del had perhaps his finest game at the plate. He knocked in seven runs with five hits, including a double and a home run. It was a memorable game for another reason: the Detroit Tigers had threatened to boycott it. It was the first game Yankee hurler Carl Mays pitched since his fatal beaning of Ray Chapman a week earlier. The Tigers ultimately backed down and played; the Yankees beat them 10-0.

The 1920 season was also the high-water mark of anti-Huggins sentiment in the press and plotting in the clubhouse. While the Yankees improved their record in each of his first three years in New York, there were constant rumors swirling that Huggins would be replaced. He had few supporters, as much because of his introspective personality as because of his small size, which translated into stature in that era. Moreover, expectations were very high in 1920, after the team had acquired Babe Ruth that January. Some of the Yankees were pushing Roger Peckinpaugh, who had run the team late in the 1914 season, as his replacement. Del was one of the anti-Huggins agitators (though Peckinpaugh was not), and he certainly did not discourage suggestions that Del would make a good successor to the little skipper.

His relations with Miller Huggins strained to the breaking point, Del began to consider career alternatives that summer, even though he was only 32 years old. He approached his former manager with the Browns (1913-1915), Branch Rickey, about college coaching possibilities.

The coaching staff University of Michigan, where Rickey had managed the baseball team, was in transition at the time. Former Chicago Cubs pitcher Carl Lundgren had been the university’s baseball coach since Rickey had left in 1913. Now, in June 1920, Lundgren was leaving Michigan to coach at his alma mater, the University of Illinois. At the same time, Michigan football coach Fielding Yost was adding the role of the school’s athletic director.

The retiring AD, Phil Bartelme, wrote Yost on July 8 that Rickey had suggested a man “none of us have thought of” for baseball coach, Del Pratt. “Branch says he is a gentleman and high class in every way; one who would take a great deal of pride in his work.” Six weeks later Rickey wrote Professor Ralph Aigler, Michigan’s faculty rep to the Big Ten Conference.

“I do not say Pratt is an ideal man for the job. I think he could be made great depending on the wear and tear of his personality. I think Pratt is honest and straightforward . . . . I know he knows baseball technically, theoretically and practically, and I am absolutely positive that he can know it from every angle. . . . There can never be any objection to him on the ground of his habits, clean speech or fairness to his men.”

Pratt had written exchanges with Bartelme in July. He wrote the AD that after he met with the “two owners” of the Yankees, he came to the conclusion “that it was every man for himself.” On August 7, 1920, he signed a three-year contract to become the coach of the Michigan baseball team and the assistant coach of the school’s football and basketball teams $4,750 a year. (His salary would rise to $5,000 and $5,250 the second and third years of the contract.) He had been making $6,500 with the Yankees.

Miller Huggins told The New York Times that Del could leave for Michigan if he wanted to; the Yankees would manage without him. The Yankee skipper would later say, “Two lawyers on one team do not make a great combination.” Huggins had a law degree from the University of Cincinnati.

“He [Pratt] was too ambitious. He wanted to manage the Yankees. Not that he hoped to tunnel under Hug, for during the last month of the season it was common gossip that Huggins was to be let out.” So the New York American explained why the Yankees traded Del Pratt as part of a blockbuster deal with the Red Sox. Del, young catcher Muddy Ruel, and two others went to Boston for a temperamental yet talented young pitcher named Waite Hoyt, veteran catcher Wally Schang, and two others. Ironically, the rumors would continue to follow Huggins, and just a year later (December 20, 1921), the Yankees traded away Roger Peckinpaugh, who had still been an unwitting rallying point for Huggins’ detractors.

The Boston press was quite positive in evaluating the 1920 Pratt trade. This comment from the Boston Globe was typical: “Schang and Pratt are the two big players in the deal, with Hoyt something of a speculation, and unless the latter should develop into a great pitcher, it looks as if the Yankees were stung.” There were also reports that Boston’s fine shortstop, Everett Scott, had been clamoring for the team to get Pratt for some time. Burt Whitman of the Boston Herald gushed that the deal must have been “conscience money” from the Yankees for the Babe Ruth deal “for surely the Sox get the cream of the talent.”

The comments of the Boston press that day were also far more revealing than those from the New York papers. The Boston Globe wrote: “Pratt and the Yankee management have been at swords points for more than a year … a club now famous for its cliques.” The Boston Herald noted that Pratt and Huggins had almost come to blows a few times that past season. In light of these strained relations, it made perfect sense for Del to explore options outside of baseball.

And so Del Pratt was sent from the Yankees, just as they were about to embark on a decade of dominance, to the Red Sox, a team entering a decade of despair. Del would have no more worries about how third-place money would be distributed. This was the first trade that the new Yankee business manager Ed Barrow, who had been the Red Sox manager, made. One of the hallmarks of his Yankees career was supporting the authority of his managers, keeping away challenges from both above and below — owners as well as players.

For a while, it seemed that Del would not report to the Red Sox and would retire from baseball. The day after he was traded to the Red Sox, the Michigan athletic director, P.J. Bartelme, was emphatic that Del was under contract to his school. Red Sox owner Harry Frazee said that he’d offer Del far more money to stay in baseball. In late February 1921, Del wrote Frazee that “it is impossible for me to resign but if you as an outsider can make it possible for me to leave with a clean slate,” he’d like to play for the Red Sox.

Frazee then sent Rickey a telegram asking him to intercede with the university on Pratt’s behalf, to release Del from his contract. Frazee said it was a “great personal favor” since surely Rickey knew “how badly I needed him.” Frazee wrote Bartelme that his situation needing Pratt was “desperate.” Only the cellar-dwelling Philadelphia Athletics had a lower batting average in the American League.

Rickey wrote Bartelme that if Pratt were not to be the Wolverine’s manager, Cincinnati Reds pitcher Ray Fisher “would be the ideal man” for the job. In a March 4 telegram, Rickey told Bartelme that Fisher “is a better man from every standpoint than anyone in the entire country, character, training and ability considered.”

Del told Bartelme he would never think of quitting and would honor the contract, but that the Boston offer was a good opportunity for his family. Del said the two-year offer would amount to $25,000 including bonuses. A clipping in his file at the University of Alabama archives noted that Boston had sent Del a blank contract and let him fill in the salary amount. He inserted $11,500 a year for two years, which would have been one of baseball’s higher salaries at the time. (Baseball-reference.com lists his Boston salary at $10,000 a year.) Del hoped the school would take that contract under consideration.

Del offered the university to refund half the salary he had received up to March 1. He also offered to return each offseason for the next three years (October 1-March 31) to assist in coaching the school’s football and basketball teams. On April 21, 1921, the Board of Control of Athletics at the university considered the Pratt case and accepted his proposal.

An Ann Arbor newspaper reported that Pratt was leaving with the deepest regret. “I am sorry that I have to go, but I feel that it is necessary. “ Spitball pitcher Ray Fisher, took over the Michigan baseball team. He would coach them to 637 wins over the next 38 years, including 15 conference championships.

Del maintained a close relationship with the University of Michigan. He helped football coach Yost during the baseball season for a few years and also coached the freshman basketball team. Del was such a favorite of the school that when the Red Sox first visited Detroit during the 1921 season in mid-May, the Tigers had a Del Pratt Day, with a section of seats set aside for Wolverines fans. Del was even honored one evening that week at a university banquet.

He had a terrific season in 1921, with career high marks in batting, on-base, and slugging averages (.324, .378, .461). His eye was better than ever; he struck out only ten times in 521 at bats. While he was slowing down on the basepaths, with only eight steals, his glovework still sparkled. He teamed with shortstop Scott for 90 double plays.

Del had another strong year in 1922, with career highs in hits, doubles, and total bases (183, 44, 259). Only now the Red Sox were a last-place team, after finishing in fifth place the year before. Gone were pitchers Sam Jones and Joe Bush, who had won more than half of the team’s games in 1922. Gone also was Everett Scott, and in midseason, third baseman Joe Dugan. All four had been traded to the Yankees.

On October 30, 1922, Del was traded to the Detroit Tigers in another multi-player deal. The key man the Red Sox got was pitcher Howard Ehmke. The submarine-style hurler did not get along with his manager, Ty Cobb. Cobb had long admired Del’s hitting skills and durability. It was an opportune move for Del — the Tigers seemed to be a team on the move. They had risen to third place in ’22. They would finish in second place in 1923 and were in the pennant race in 1924 for much of the summer. After leading the league in late July and being only a half-game back in mid-August, they finished six games out of first place.

While Del’s bat was as potent as ever, hitting over .300 both seasons, it was not a good trade for the Tigers. Del turned 35 shortly after the trade and missed 86 games in 1923-1924. And he “had slowed down to a walk,” as Fred Lieb said (The Detroit Tigers). After playing more than 1,500 games at second base (and less than 50 games at other positions), Del was moved to first base during the ’23 season. He played the bulk of his games there the next year and a half.

The worst part of the deal from the Tigers’ standpoint was that they gave up on an excellent pitcher. Howard Ehmke won 39 games in 1923-24, an incredible 30 percent of the Red Sox victories. In 1924, as in 1915 and 1916, the Tigers might have been just one starting pitcher away from the AL pennant.

Despite hitting above .300 for five straight seasons (in which he averaged almost 500 at bats), Del was released by the Tigers after the 1924 season and waived out of the league. He had slowed down significantly in the field, as reflected in his lower Chances per Game numbers. He finished his major league career with just under 2,000 hits, of which 20 percent were doubles and 25 percent were doubles and triples. Del was one of the few men who played regularly (more than 120 games) and hit over .300 in both his first and last major league seasons. He was also one of a handful of players who appeared in all of his team’s games over three seasons for three different teams (Browns, 1913, 1915, 1916; Yankees, 1918, 1920; Red Sox, 1922). Another player who started in St. Louis, Rogers Hornsby, matched that mark, with the Cardinals, Giants, and Cubs.

That fall and winter of 1924-1925 was the first time since 1910 that Del did no college coaching. He was managing a sporting goods store in Ann Arbor, Michigan, where he lived. Before long, Del realized he wanted to stay in the game of baseball. It was time for him to pursue a career in managing and coaching, yet he wasn’t ready to retire as a player.

So Del embarked on a career as player-manager for the Waco Cubs of the Texas League. The town was returning to the circuit after an absence of five years, replacing Galveston. They played in old Katy Park, (later torn down for a junkyard), just north of old Baylor Stadium, near the Cotton Palace Fairgrounds.

Del went on a three-year tear of offensive output. From 1925 to 1927, he averaged 28 home runs, after hitting just three circuit blast a year in the preceding five years. In 1925, he watched another former St. Louis major leaguer dominate the Texas league power stats: Big Ed Konetchy led the league with 41 homers and 166 runs batted in, for Ft. Worth. 1927 was Del’s turn.

At the age of 39, Del put together one of the great seasons a player-manager in the high minors ever had. He won the Texas League Triple Crown: a .386 batting average with 32 home runs and 140 runs batted in. That 1927 team also had the best batting average in league history, .316. The starting outfield of Max West, Randy Moore, and George Blakely all hit at least .360. In his next three years with Waco, Del played a number of games at the corners (first and third base), which were less demanding than his regular position. Del had only 91 at-bats in 1930, though he still saw the ball pretty well; he hit .374.

Del gained a reputation for developing young talent. Among his players who had success in the bigs were Andy Cohen, Willis Hudlin, Tony Piet and Art Shires. Yet with the exception of their second-place finish in 1927, Del’s Cubs had losing records. Their problem usually was a lack of good pitching. Del was part of two significant games in Katy Park in his and his team’s last year in Waco. The first Texas League night game was played there on June 20, 1930, against Fort Worth. On August 6, Waco left fielder Gene Rye hit three home runs in the eighth inning, in a game against Beaumont, won by Waco, 20-7.

In 1931, when Texas League ball moved back to Galveston (from Waco), Del went along as manager of the Galveston Buccaneers for two seasons. In 1931, he watched a couple of future St. Louis stars excel with Houston: Dizzy Dean and Joe Medwick. And the following year, former Browns teammates Hank Severeid and George Sisler (the latter for just part of the season) were fellow Texas League managers. In 1932, Del had his last plate appearances at the age of 44, when he hit .293 in 41 at bats. Del still had his temper, occasionally being tossed out of games. But a Texas League umpire who had to put Del out more than once — Stephen Basil — paid Del a compliment: “But I’ll say this for Del — he never carried a grievance after a game.”

In 1933 Del was out of baseball, while he operated a bowling alley in Galveston. He returned as manager and business manager of the Fort Worth Cats the following year for his final season managing baseball. Three years later, he was one of 403 retired players who received lifetime passes from major league baseball. In its April 7, 1938 issue, The Sporting News reported that Larry MacPhail signed Del as a West Coast scout for the Dodgers. In the late 1930s, he coached the Kirwin High football team in Galveston.

With his baseball days behind him, Del now had more time for two of his passions, hunting and fishing. He spoke of those pursuits this way: “Many of the stories of fishing and hunting you hear are true, but are so fantastic people think they are lies. I guess most people think hunters and fishermen are liars anyway. That’s why I call hunting and fishing the liars’ sports.”

Del surfaced in baseball news in the early 1950s. In July 1951, he took part in two old timers’ games in Houston between the Houston Buffaloes and a team of Texas League all-stars. Del managed the game, which honored Tris Speaker, who had played for Houston in 1907. A year later, Del played an inning at first base for the all-stars. The biggest cheers were for Firpo Marberry, who had recently lost an arm in a car accident, when he struck out the one man he faced on three pitches. Later that year, Del ran for the presidency of the Gulf Coast League, which was placing a franchise in Galveston in 1953, and lost in a close race.

Del continued to live in Texas; he stayed in Galveston for the rest of his life. For many years he owned a gas station at 31st and Boulevard. The Galveston Isle featured Del at his beachfront service station in its July 1948 issue. When The Sporting News reported late in 1938 that Del had applied for the job of manager of the Dallas Steers (Texas League), he denied the story, speaking of his “thriving oil and gas business.” In 1962, the Galveston Daily News had a feature on Del, who was managing the sporting goods department of a Thrifty Discount Store.

In a rich baseball career of more than two decades, including thirteen years in the bigs, Del Pratt was part of a lot of baseball history. He lived for more than 40 years after leaving the Detroit Tigers. When he was inducted into the Alabama Sports Hall of Fame in 1972 at the age of 84, he told the Galveston Daily News, “I’ve got a pretty good record. But I don’t talk about it much.” Del died on September 30, 1977 at age 89.

Last revised: August 23, 2020 (ghw)

Partial bibliography

Pratt clipping files, Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, New York, and The Sporting News, St. Louis.

Telephone interviews with Donald Pratt, Pasadena, Texas, (Del’s son); James Pratt, Birmingham, Alabama (Del’s nephew); Del Pratt III, Dunedin, Florida (Del’s grandson).

Pratt family scrapbook and clippings.

Alabama Sports Hall of Fame, Birmingham.

Bryant Museum, University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa.

Rosenberg Library, Galveston, Texas.

University of Michigan archives.

Newspapers and magazines:

Boston dailies (Globe, Herald, Journal, Post) for Pratt wedding and trades.

Galveston Daily News

New York Times

New York Evening Telegram

The Sun, New York

The World, New York

Globe-Democrat, St. Louis

Post-Dispatch, St. Louis

The Republic, St. Louis

The Times, St. Louis

Sporting Life

The Sporting News

Baseball Magazine

Books

Robert Finch. The Story of Minor League Baseball. Columbus, OH: Stoneman, 1952.

Mark Gallagher. New York Yankees Encyclopedia. Champaign, IL: Sports Publishing, 2001.

Frank Graham. The New York Yankees, An Informal History. New York: Putnam, 1958.

Lloyd Johnson and Miles Wolff, eds. Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball. Durham, NC: Baseball America, 1997.

Fred Lieb. The Detroit Tigers. New York: Putnam, 1946.

Fred Lieb. The St. Louis Cardinals. New York: Putnam, 1944.

Bill O’Neal. The Texas League: 1888-1987. Austin: Eakin, 1987.

Marc Okkonen. Ty Cobb Scrapbook. New York: Sterling, 2001.

David Porter, ed. Biographical Dictionary of American Sports, Baseball. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 2000.

Lyle Spatz. Yankees Coming, Yankees Going. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2000.

SABR members, including Tom Bourke and Bill Nowlin.

Statistics

www.baseball-reference.com.

Bill James, John Dewan, Neil Munro, and Don Zminda, editors, Stats All-Time Major League Handbook, Stats Inc. 1998.

John Thorn, Pete Palmer, Michael Gershman, editors, Total Baseball, 7th Edition, Total Sports, 2001.

Full Name

Derrill Burnham Pratt

Born

January 10, 1888 at Walhalia, SC (USA)

Died

September 30, 1977 at Texas City, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.