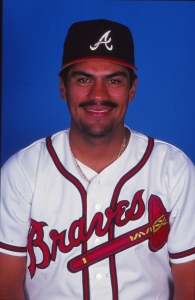

Eddie Pérez

Catchers, like musicians, use both hands for their craft: the gloved one captures the ball while the other acts as a conductor’s baton to guide the action. Johnny Bench, arguably the best player to don the tools of ignorance, stated, “The catcher is in the middle of everything. He sees it best.”1 The statement is both literal and figurative; not only is he the sole defensive player with a frontal view of the mound, but it is his guidance that traditionally starts every micro-battle between hitter and pitcher. Braves fans — both the ones in the South and those who were raised on “America’s Team” during their TBS heyday — were privy to a clinic in the late 1990s thanks to Eddie Pérez.

Catchers, like musicians, use both hands for their craft: the gloved one captures the ball while the other acts as a conductor’s baton to guide the action. Johnny Bench, arguably the best player to don the tools of ignorance, stated, “The catcher is in the middle of everything. He sees it best.”1 The statement is both literal and figurative; not only is he the sole defensive player with a frontal view of the mound, but it is his guidance that traditionally starts every micro-battle between hitter and pitcher. Braves fans — both the ones in the South and those who were raised on “America’s Team” during their TBS heyday — were privy to a clinic in the late 1990s thanks to Eddie Pérez.

Born on May 4, 1968, Eddie was blessed with a comfortable upbringing in then-prosperous Venezuela. For most of the second half of the twentieth century, the country’s vast oil reserves afforded a standard of living envied by its Latin American neighbors. Growing up in Ciudad Ojeda in the state of Zulia, he and his siblings enjoyed the allure of baseball without the sport representing a one-way ticket out of poverty: “My family loved baseball. … All my brothers and my dad played. I don’t recall specifically when I started.”2 His father worked in the oil industry as a shore captain and his mother stayed at home with the children. (Both parents now reside in Atlanta.)

Although the Águilas of Zulia played in Maracaibo, only 90 minutes across the namesake lake, Eddie rooted for the Tigres of Aragua, who played more than seven hours away, near the capital city of Caracas: “My dad took me to see two games. Zulia played against Aragua and I preferred the latter, even though people rooted for the Águilas.” Later he lived out two dreams, playing 10 winter-league seasons with his favorite club before winding down his active career at home: “Aragua traded me to Zulia, which hurt me a lot; it was a transition, but I liked playing at home, seeing my family and friends on the stands.”

Perez was mesmerized by the exploits of Davey Concepción, the National League’s premier shortstop during the 1970s and a vital member of the fearsome Big Red Machine. In the days before cable broadcasts, a “game of the week” was the main drug to fuel the country’s baseball addiction, and appearances by Cincinnati were appointment television. Concepción was the heir to “Little Louie” Aparicio, whose Spanish nicknames focus on his stature on the diamond: “El Grande” and “El Rey David.” Much like Puerto Rican players wearing number 21 in honor of Roberto Clemente despite being born after his tragic death, Aparicio’s contribution to the fertile grounds of Venezuelan baseball has bloomed for generations after his retirement. As Aparicio’s number 11 and Concepción’s 13 were popular, Eddie opted to split the difference and choose number 12.

Prior to Cal Ripken and Alex Rodriguez, shortstops were hardly tall, and Eddie had grown to 6-feet-1 by his teens. Eddie did not have to look far to determine a position to play: His father was a celebrated amateur catcher. In the major leagues, Baudillo “Bo” Díaz had replaced Bench behind the plate in Cincinnati, giving Venezuelans another established big-league hero. Though Eddie and Bo never met, they share a connection via Carlos Hernández, Eddie’s contemporary behind the plate in the big leagues. Díaz played with Hernández in Venezuela and the latter, in turn, shared some of those tips with Pérez.

At the tender age of 7, Eddie was turning enough heads to play his first children’s Campeonato Nacional. Blessed with the twin graces of natural ability and a patient father who taught him the fine art of catching, he progressed through the youth levels to star in the 1986 Big League World Series tournament in Fort Lauderdale, Florida. Venezuela lost its first game against Taiwan but then reeled off eight consecutive victories to win the tournament. Eddie earned Most Valuable Player (MVP) honors with seven home runs and 16 runs batted in.3 The event, held from 1968 through 2016, picked up where the Little League World Series ended, affording 15- to 18-year-old youth the opportunity to showcase their talents in front of scouts. It was Venezuela’s first and only title, prompting joy in the state capital of Maracaibo and a massive opportunity for Eddie, but his decision was far from easy.

In the days before cell phones and email, messages were relayed via landline telephones and intermediaries; his performance in Fort Lauderdale garnered Eddie some scout interest and the chance to further impress the scouts. “The Aguada Tigres gave me a tryout; about 50 or 60 kids showed up, 10 of whom were from Zulia, like me. I was the only one signed. Since I was underage, my dad said: ‘Here’s the deal, $15,000 is more than I’ve ever earned in a year. That means nothing, though: It’s your decision.’”

Having finished high school, Pérez was planning to enroll in college like his older siblings and weighed the pros and cons of leaving Venezuela to prove his mettle in the United States. “My dad asked if I was sure if I wanted to sign the contract. My brothers criticized me — ‘Are you crazy?’ they would say.” He remembers his father cautioning him how life would change: While he would indeed be playing baseball, he’d have to cook for himself, launder his clothes, and handle a host of other domestic duties typically glossed over by scouts spinning tales of stardom and riches. Pedro González, himself a former major leaguer with the Yankees and Indians, gave Pérez an honest opinion of the opportunity: While the $15,000 offered by Atlanta was a sizable sum, Eddie also had an offer with his favorite club, the Tigres de Aragua, for 200,000 bolívares, (about $10,700, 18.7 bolívares being worth $1 in early 1986).4 “It was both luck and a blessing to follow my dad’s footsteps (playing catcher). Eight years in the minors, always as a backup, followed by 11 years in the big leagues and another 10 as a coach. Every career has obstacles and I never gave up. Moreover, the franchise taught me not just to be a good ballplayer but also a good person, off the field and with the community. I’ve been with them more than 30 years.”5

Ultimately Pérez decided to follow his dreams. After signing with Atlanta on September 27, 1986, he packed his bags for the Gulf Coast League, where he started the 1987 campaign. Playing with future big leaguers Derek Lilliquist, Keith Mitchell, and Ben Rivera, Pérez appeared in 31 games and fielded at a .980 clip while hitting .202. The team finished last with a 20-43 record but gave the 19-year-old his first exposure to life outside of Venezuela.

It was a slow climb for Pérez. He amassed 721 games in the minors across the Gulf, Class A, Double A, and Triple A affiliates of the Braves franchise. The 1988 season saw him at Burlington of the Midwest League, with another last-place finish; 1989 at Sumter of the South Atlantic League, with a club 1½ games out of the cellar; 1990 split between Sumter and Durham (Carolina League), where both clubs posted winning records; 1991 between Durham and Greenville (Southern League). The 1992 and 1993 seasons were spent at Greenville and 1994/1995 at Richmond (International League) before Pérez got the much-desired call from Atlanta. From 1987 through 1995, he played in 698 games in the minors, garnering 2,456 plate appearances and producing a .246 batting average. (After establishing himself in the majors, Pérez played 23 minor-league games in 2001 and 2006 during rehabilitation assignments.)

On September 10, 1995, he debuted in the major leagues in Miami, pinch-hitting in the getaway game of a series against the Marlins. Although the Braves were six weeks away from winning the World Series, they lost that contest 5-4 in extra innings. Greg Maddux started but pitched only one inning, as Atlanta manager Bobby Cox gave work to six other hurlers in preparation for the extended postseason (this was the first campaign with the Division Series, since the 1994 strike canceled the playoffs). With the score tied, 4-4, Mark Wohlers’ spot was up in the 10th inning and Pérez was summoned to bat against Terry Matthews. He recalled the game fondly, stating, “I was happy in the big leagues after so many years in the minors. In the last game of the series, I was asked by Bobby Cox to bat and I struck out.” He caught Pedro Borbón Jr. for two innings and witnessed former Brave Terry Pendleton cross the plate for the Marlins win.

Of the 120 major-league baseball players whose first career at-bat produced a home run, two have been Venezuelans: Gerardo Parra (2009) and Alex Cabrera (2000).6 Pérez narrowly missed being the first, leaving the yard for his first hit during his first start (and second plate appearance) on September 15, 1995. While Atlanta had already clinched the NL East (and ended up winning by a comfortable 21-game margin), the game was far from meaningless. Pérez recalls not just the game but the circumstances with flawless details: “Pat Corrales called me and said: ‘I have good news and bad news: You’re starting but you’re catching John Smoltz, who had been struggling.’ Javy López told me ‘good luck.’… Charlie O’Brien said good luck too, but stay calm, call your game. Smoltz shook me off twice: Barry Larkin hit a home run and Hal Morris doubled. He struck out 11 batters in eight innings pitched and (Greg) McMichael closed.”

Starting behind the plate for the first time, Pérez hit seventh in the batting order and recorded 12 putouts, one assist, and one double play. Pérez connected off veteran left-hander Mike Jackson in the seventh inning to drive home David Justice. The home run provided the difference as the Braves beat the Reds 3-1 in front of 31,882 fans for Smoltz’s 11th victory of the season and McMichael’s second save. The first of Pérez’s 40 career round-trippers was particularly memorable: His boyhood idol Concepción was on hand during one of his appearances at Riverfront Stadium. They met and shook hands after the game. During Pérez’s phone call to his parents’ home, it was hard to figure out which accomplishment pleased him more: “The game ended, and I was so happy, calling my family from a pay phone and when I left the stadium I ran into Davey who was there signing autographs. He came over. … I couldn’t believe it, this was my dream, my first hit, and meeting Davey. I still have the ball.”

For the season, Pérez appeared in seven games and had four hits in 13 at-bats; he struck out twice, did not walk, and collected a double in addition to the earlier home run. He pinch-hit, started another game at catcher supporting Steve Avery, pinch-ran, and played first base for half a game. As the backstop, he tallied 25 innings with no errors, two assists, and two double plays; the starters yielded only two runs in 18 innings over the two games he started, demonstrating a facility to call the game. The Braves opted not to include him in the postseason roster, choosing the regular-season tandem of O’Brien and López for all three rounds. The Braves, however, liked what they saw from Pérez and declined to offer O’Brien an extension after the World Series, making Pérez the heir to the second catcher spot on the roster.

The 1996 and 1997 seasons brought plentiful action for Pérez. As the backup catcher, he played in 141 total games, collecting 373 at-bats and 81 hits, 25 of which were for extra bases. He tasted the postseason in both years, playing in 10 games but reaching base only twice, on a hit against the Dodgers in the NLDS and a walk against the Cardinals in the National League Championship Series, both in 1996. The Braves, so-called team of the 1990s, played good baseball against the Marlins and the Yankees but could not best their foes in the fall.

In 1996 Pérez saw action in 68 games, 39 as a starter. The Braves were 26-13 with his name in the starting lineup. He had a six-game hitting streak and at one point reached based in eight consecutive games. The back-of-the-baseball-card statistics did not tell the whole tale; as the Braves knew, his game-calling abilities provided value beyond his offensive output. Braves pitchers compiled a 3.02 ERA when he was their backstop, more than half a run better than starting catcher López. The next year, his batting average dipped by 41 points (from .256 to .215) while his OPS dropped by more than 100 points (from .697 to .594). His handling of the staff continued to be exemplary, with a catcher’s ERA of 3.24 as the Braves led the league with a 3.18 mark.

The 1998 campaign yielded batting highs for Pérez. Appearing in 73 games and garnering 206 plate appearances, he hit .336 with a .404 OBP and a .537 slugging percentage. Pérez attributed his success to a sound mindset: “I want to remain here, and I need to hit. If I don’t, I won’t stay. Great hitting catchers like Javy and (Mike) Piazza were there … so I focused on hitting.” While his lumber was white-hot, his focus on the mound did not waver; Braves pitchers allowed a scant 2.60 runs per nine innings when he was on the lineup. Atlanta’s starters combined for 88 victories with Glavine picking up 20, Maddux earning 18, Kevin Millwood and Smoltz tying at 17 and Denny Neagle winning 16 as the team’s fifth starter. The juggernaut finished the campaign at 106-56, establishing a franchise record.

Pérez also found an unlikely source of hitting prowess: Maddux. “Few people know this, but Maddux knows more about hitting than pitching. He wouldn’t talk more unless asked. … In LA, I said if I don’t hit, I am not sure I won’t catch you again. He said try to hit to third base. That day I had three hits. I asked him why he hadn’t told me before; he said, ‘You never asked.’” Beyond Maddux, Pérez sought hitting tips from Chipper Jones, former teammate Fred McGriff, and fellow Venezuelan Fred Manrique. He was consistent throughout the year, overcoming a 1-for-8 start with three multihit games in April to reach .385 by month’s end. His average dipped below .300 for only a fraction of July. Although Atlanta swept the Cubs in the NLDS, the Braves fell to the San Diego Padres in the NLCS in six games. Pérez collected three hits against the Friars and one against the Cubs, establishing personal postseason marks he would shatter the next year. The sole hit against Chicago was decisive, an eighth-inning grand slam off Rod Beck to give the Braves and Maddux the win.

The 1999 season saw Atlanta seek an elusive second World Series title en route to its seventh consecutive division championship. (The Braves accomplished the task during 14 consecutive seasons, a major-league record, although one aided by the cancellation of the 1994 postseason since they trailed the Montréal Expos.) Pérez appeared in a career-high 104 games due to his former minor-league roommate Lopez’s season-ending injury in late July. Though he hit a pedestrian .249, his on-base average and slugging both improved by 21 and 39 points after his playing time increased in August and September. Despite the extra games and the sweltering Georgia summer, Pérez logged a 3.55 catcher’s ERA on 3,182 opponents’ plate appearances, the second-best mark in the majors for backstops with such workload. He powered the Braves to a World Series appearance by hitting .500 while slugging .900 against the Mets in the NLCS. Pérez was voted the series MVP, echoing his 1987 amateur accolades. Had fans been told before the series began that a catcher would win the award, most would have guessed future Hall of Famer Piazza, who donned the mask for the Mets. However, Piazza was not in a groove, going 4-for-24 during the six-game affair.

While expectations were high for the World Series (a rematch of the 1996 fall classic), Atlanta could not answer the Yankees, who swept the Braves en route to their third title in four years.

With López back to full health in 2000, Pérez returned to full-time backup duty. He suffered through right-shoulder injuries in consecutive seasons, suiting up for only 32 combined games in 2000 and 2001.7 The Braves nevertheless won the NL East but failed to advance to the World Series, dropping three straight contests to the Cardinals in the 2000 NLDS and a tough five-game series against eventual champion Arizona in the 2001 NLCS. Pérez watched the postseason from home while nursing his injuries.

The 2002 season saw Pérez switch leagues for the first time, after the Braves traded him to Cleveland for a player to be named later (Jason Fitzgerald) on March 28. Eight days earlier, Atlanta had shipped Paul Bako and José Cabrera to Milwaukee for Henry Blanco. A fellow Venezuelan, Blanco was two years younger than Pérez and had averaged close to 100 games for the Brewers in the prior two seasons. He played until age 41 in the majors, appearing in 971 games (914 as the catcher), a representative of the strong Venezuelan catching corps that followed Pérez. Steve Torrealba, a second-generation Venezuelan major leaguer, played a handful of games for the Braves as well in 2002, having debuted in the big leagues the prior October against the Marlins by replacing Pérez in the ninth inning and singling in his first at-bat. Though Pérez was leaving the Braves, his mark on the franchise was well-felt and his countrymen had set up a club behind the plate.

With the 74-88 Indians, Pérez appeared in 42 games in 2002. While the team was 18-24 in games he played, they were 16-18 in his starts, proving his ability to manage the pitching staff, as attested by his 4.37 catcher’s ERA, three-quarters of a run better than starting backstop Einar Díaz’s 5.18. The Indians were in transition, fielding a team with veterans like future Hall of Famer Jim Thome, Omar Vizquel, Ellis Burks, Bartolo Colón, and Chuck Finley, alongside youngsters CC Sabathia and Milton Bradley. Pérez backed up Díaz but also provided tutelage to a young Víctor Martínez, who was beginning his career in the majors. Pérez knew his stay with the Indians would be short-lived, given the promise of Martínez and the presence of a younger option, Josh Bard, on the roster.

The 2003 season brought him back to the National League with the Brewers, who were in the 11th of a brutal stretch of 12 consecutive losing seasons. Pérez was the main catcher for Milwaukee, appearing in 107 games and slashing .271/.304/.420 while playing his customary solid defense. The Brewers improved their 2002 mark by 12 games, though their pitching worsened by almost a third of a run. Pérez hit his second (and last) career regular-season grand slam in San Diego, victimizing Carlton Loewer on May 28 in the first inning of an 8-6 loss, and his only career walk-off round-tripper, against Cincinnati’s Scott Williamson on May 17. His batting average reached .316 in the summer, but he fell into a slump to finish the year.

The Brewers did not offer Pérez a contract for 2004, granting him an opportunity to reunite with the Braves. Although only Chipper Jones and John Smoltz remained from the 1990s core, Pérez welcomed the opportunity to show the ropes to young prospect Brian McCann, who would enjoy seven All-Star seasons with the Braves. Pérez played in 74 games, collecting 39 hits (15 of which were for extra bases) as the Braves reached the NLDS in 2004. Atlanta lost a hard-fought series to the Astros in five games, three of which Pérez entered as part of a double switch. He was hitless in three at-bats.

Baseball is at its core a game of matchups. Every manager seeks an advantage, no matter how small, against his opponent. Often the pendulum swings in unexpected ways, as was the case of Randy Johnson and Pérez. By the time both met on May 18, 2004, Pérez boasted of a 6-for-13 batting line against the Hall of Fame-bound lefty. In their last matchup, he was tasked with a seemingly impossible feat: pinch-hit against the Big Unit as Johnson attempted to pitch a perfect game. “I think I hit .400 or .500 vs. RJ. I was surprised that day that I wasn’t in the starting lineup since Bobby liked to play the hitters with strong history. I was watching the game and Pat said, you’re going up, and I grabbed the bat. Everything was working for Randy; I could see how he was dominating all our hitters. One of my most memorable at-bats … perfect games are so hard to do.” Facing a 98-mph fastball, Pérez struck out to end the game.

The 2005 season proved to be a tough one for Pérez. After appearing in 15 games through May 18, he did not see action until the end of the year due to tendinitis in his right shoulder. Brian McCann established himself as the regular during his absence, wrapping up the season with a .745 OPS as a 21-year-old and helping the staff finish sixth in NL ERA. Pérez’s curtain call came on September 27, 2005, during a 12-3 blowout against the Rockies. He pinch-hit for Danny Kolb and grounded out on a 2-and-1 pitch from Randy Williams. He had made his final on-the-field appearance on May 14, starting behind the plate and guiding Mike Hampton to two innings of work and Adam Bernero to three frames before yielding to Johnny Estrada.

The Braves signed Pérez to a minor-league deal on January 6, 2006, and he did not return to the majors. He appeared in 13 games for the Southern League’s Mississippi Braves and provided a veteran presence for prospect Jarrod Saltalamacchia. He played an unofficial role assisting his former teammate Jeff Blauser, who managed the team. The franchise was transitioning; it would experience its first losing season since 1990, failing to make the postseason. During Pérez’s years with the Braves, the team played deep into every October, but the next playoff trip would not come until 2010.

To watch Pérez catch Maddux was akin to seeing a world-class ballet performance between favorite partners. Baseball players in general are creatures of habit but pitchers are more inclined to seek the comforts of routines. The sabermetrics explosion has given us statistics like pitch framing and catcher’s ERA to better measure the defensive contributions of catchers. Savvy pitchers, though, have long trusted their feelings, recollections, and overall easiness by “feel.” Like a nervous animal prognosticating an earthquake, they just knew. During their tenure with the Braves, Maddux and Pérez teamed up for 832⅓ innings, dozens of wins, and hundreds of moments that could serve as clinics for players and fans alike.8

On June 17, 1996, Pérez found himself in the starting lineup for Maddux’s start. He tripled and supported Maddux’s eight innings with zero walks and only four hits allowed. The relationship clicked to such a degree that the rest of the campaign saw a marked difference in the pitcher’s effectiveness: His 1.89 ERA in Pérez’s 114 innings caught was about half of regular López’s 3.44 ERA in 131 innings. While the proper calculation and recording of catcher’s ERA was not yet en vogue, the organization took notice and made Pérez the starter for Maddux’s starts the rest of the year despite the more potent bat of López.

Maddux’s exploits are legendary, and readers wishing the stories were apocryphal may be surprised. While the tandem had played together during 1994 and 1995 spring training, the decision to pair them was made by Cox, who noticed the ace’s level of comfort with the team’s backup catcher. Unlike other positions, where starters are expected to play 95 percent of the games, a starting catcher may average 120 to 130 starts to account for the wear and tear on the body and the “always-on” concentration before, during, and after the game. While a position player must account for the opposing pitcher’s “stuff,” a catcher must prepare for every single one of the other team’s players.

Pérez himself was eager to praise Maddux. From the way he caught the ball to the way he held it in the right hand, Maddux was always providing signals on his preferred methods. Seemingly insignificant gestures like the way he touched his cap — typically a signal between hitters and third-base coaches — gave Pérez clues on what Maddux was thinking. The pitcher’s 1994-1995 partner in crime, O’Brien, had departed for Toronto during the 1995 offseason. The organization knew, from the small sample of 1994/1995 spring training games and a batch of September contests, that Pérez was ready to fulfill two roles: overall backup and Maddux’s catcher. Although the baseball fan saw their connection only on the field, they also spent time in the dugout, going over hitters and observing the intricacies of the opponents’ lineups. Pérez took the opportunity to ask Maddux questions about each situation for future reference: “Umpires would often ask me how come Maddux never pitched a no-hitter. I would say he didn’t want to. … He purposely wanted batters to have some hits off him so he could dominate them the next time.”

Pérez never took the opportunity for granted, but he worked hard to ensure that the Braves star was comfortable on the mound. “I never heard that Maddux demanded me as his catcher,” Pérez said. “It was Bobby’s decision. It started in the 1994 spring training, he seemed at ease with me. In 1995 spring training I caught a lot of his games too and Bobby noticed. I think it also had to do with ensuring Javy had a day off and I had a day to play that was scheduled. Communication between Maddux and me was important; he wanted us to sit together and talk about the game and a lot of people didn’t see that. Perhaps Maddux told Bobby, I don’t know. Maddux was different, I learned quickly, and Charlie O’Brien helped me tremendously. When we first started, he’d tell me what to throw — a lot of people didn’t know it. I had to learn fast; in a month I picked up and wanted to call the game. He shook me off three times, and I asked him how we did. He jokingly said it was three times too many. I learned a lot from him that has helped me not only as a player but also as a coach.”

Pérez’s favorite anecdote about Maddux: “In 1998 we were discussing the opposite team, going over batter by batter, how to pitch to each in individual situations. Against Jeff Bagwell, nothing inside, everything outside. In the seventh or eighth, we were ahead 8-0, Bagwell came up with the bases empty. Maddux said inside and I was annoyed; I always wanted to be on the same page as Maddux. He shook me off three times and said inside. I thought he was crazy. … Bagwell hit a massive foul shot and Maddux still asked for it inside. Next pitch, home run, a long shot. I was mad and asked him why, he said we’ll talk later. Maddux pitches eight innings and then Wohlers picked up the save in the ninth. In the dugout I was mad at him and he said, ‘In two months, Bagwell will come up and seek that pitch.’ Two months later, in Houston, Bagwell came up with two men on base, we were up 3-1 in the seventh inning, Bagwell sought the inside ball, but Maddux pitched three outside changeups to strike him out. I was happy celebrating and thought he’d be mad as he didn’t like such emotions during the game. … So he pulled me aside and said, ‘Remember two months ago? The pitch we threw him?’ I didn’t recall at the time, but thought about it, and then remembered the prior pitch.”

Has the anecdote been embellished? Perhaps, but much like a myth, it has plenty of historical origins. Rob Neyer tried to verify it and found one instance of its possible occurrence.9 He concluded that the story wasn’t as “good” as originally called, but one might beg to differ. Maddux “allowed” the round-tripper to Bagwell while staked with a four-run lead early in the game, rather than in the later innings. This attests to the pitcher’s confidence in his stuff, his catcher, and his team’s offensive prowess. The comeuppance did not occur late in a playoff game, but rather early in one (first inning). But the result was the same: Bagwell chased a pitch Maddux knew he’d be seeking.

Like many Latin American players, Pérez could not resist the siren song of winter baseball. He returned to Venezuela for 12 straight campaigns (1987-1988 through 1998-1999), playing in 420 regular-season games and another 72 in the postseason. He won two Golden Gloves (1993-1994 and 1994-1995) and was selected as the league’s MVP (known as the Vitico Davalillo Award) in 1994-1995. Aragua won 34 games and lost 26, placing second in team ERA (2.78) and third in team batting (.262). The magic did not carry over to the round-robin: Aragua finished last with a 3-9 mark as their bats and arms grew cold.10 (Winter Leagues in the Caribbean typically begin in November and go through January, so they are titled after both years.)

After the 1996-1997 season, Pérez was traded to Zulia, where he would finish his playing career. His lifetime numbers (.254 average in 1,564 at-bats) are eerily similar to his major-league tally of .253 in 1,525 at-bats.11 While his playing career in the winter leagues did not result in a league title, Pérez was able to play with many major leaguers, including Concepción for the latter’s final three campaigns in the Venezuelan circuit.12 However, Pérez’s voyage into the Venezuelan record books did not stop with his retirement.

Bitten by the coaching bug with Atlanta, Pérez was tapped to lead the Zulia team in 2008-2009 and 2009-2010, posting a 61-66 regular-season record and a 9-18 mark in the postseason. He returned in 2014-2015, compiling a 35-28 line good for third place. More than 20 major leaguers played for the team, including fellow Venezuelan catcher Sandy León, who established himself as a “pitcher’s catcher” for the Boston Red Sox.

In 2015-2016 Pérez moved to the Aragua franchise. Though the Tigres had won the title in 2003-2004, 2004-2005, 2006-2007, 2007-2008, 2008-2009, and 2011-2012, they’d been led by a foreign-born manager. Pérez managed the club to the Venezuelan Winter League title, and became the first criollo, or Venezuelan, to achieve the goal for the franchise.13 The team became the runner-up in the Caribbean Series, losing a tough final game to México’s Venados of Mazatlán.

“Specialist” is sometimes a backhanded compliment in baseball. Stone-gloved hitters are often derided as “DH’s in waiting.” Lefty-One-Out-Guys (LOOGYs) are lambasted for lengthening the game and slowing its pace. Charlie Finley even employed a “designated pinch-runner,” the much-derided Herb Washington who would not enjoy a single plate appearance but appeared in 105 major-league games and scored 33 runs.

Historically, shortstops and catchers have seen their defensive value weighed above their offensive contributions. Paradoxically, the pendulum is swinging away from shortstops and toward catchers as more complex and definite metrics to value fielding contributions gain popularity among fans and front offices. General managers have, perhaps belatedly, recognized catchers’ contributions beyond passed balls and caught-stealing percentage to include pitcher effectiveness, once thought to be the sole responsibility of hurlers. Yet while Joe Tinker and Ozzie Smith have gained Cooperstown immortality thanks to their leather exploits, catchers with similar careers (Bob Boone, Jim Sundberg, Jason Kendall) have been all but ignored by voters.

Catchers are like teaching assistants, their entire livelihoods providing an apprenticeship not enjoyed by the other positions. Yet this trait is often missed by even hard-core fans. The Milwaukee Brewers’ classic logo combined a “B” for Brewers and a “M” for Milwaukee into a silhouette of a catcher’s mitt that many missed, much like the contribution of the masked men.

Catchers are the second least represented position in Cooperstown, with only 18 immortalized with a Hall of Fame plaque. (The fewest are the 17 third basemen.) Only two backstops have made it in their first year of eligibility, Bench and Iván Rodríguez. Not Yogi Berra (second year). Not Roy Campanella (seventh year). Not Bill Dickey (11th year). Not Piazza (fourth year). Catchers are unlikely to spend 20 years in the majors as their wear and tear is evident even if they switch positions in their older years (as Bench and Berra did), so their opportunity to amass counting statistics like hits and runs is limited, making their offensive numbers less impressive than those of their teammates.

Their job is never done; every game has a post-mortem to discuss what worked, what did not, and what should change. While other positions receive such scouting updates, they do not generate the due diligence expected of the catcher, whose view includes not just the pitcher and his mechanics but also the placement of the fielders. Given that only 70 percent of plate appearances yield a play on the field, their position plays an outsized role in the outcome of a game.14

Like a Sherpa, the catcher guides the pitcher through the game, but his responsibility changes as the game progresses. The average 2018 major-league game saw 4.5 hurlers take the mound; yielding new personnel, new conversations, new signs, and new strategy.15 These tasks were added to the time squatting behind the plate, catching 100-mph balls, handling wild pitches and foul tips, focusing on the baserunners, and ensuring that the pitcher’s confidence is strong regardless of the scoreboard. A baseball card, often focused only on hitting prowess, cannot adequately capture the catcher’s performance, which is much more correlated to the team’s winning percentage than to any other measure.

After the 2006 season, the Braves offered Pérez the role of bullpen coach, understanding that his wealth of knowledge would be integral to the young roster. The Braves had finished 2006 with a 79-83 record, the first losing campaign since 1990. Pérez kept the role for a decade (until 2016), seeing the team both rise and fall again in the NL East. He was shifted to the first-base job on May 17, 2016, and kept the position until the end of 2017, bringing a total of 11 full seasons as a member of the Braves’ major-league coaching staff.16

Pérez’s son Andrés was drafted by Atlanta in the 36th round of the 2016 amateur draft.17 Buoyed by the robust support network of American collegiate sports and academics, the 6-foot-7 Andrés received a scholarship to the University of North Georgia.18 Pérez the elder recognized the opportunity but was quick to highlight the reality: “It is different than in Venezuela. There I would have gone to study and forgotten about baseball. My son can play and study. Had he been in Venezuela, I would suggest he take the $5,000 or $20,000 given the reality of the country.”

Pérez enthused about the new wave of his countrymen reaching the major leagues, although as a proud Venezuelan, he is heartbroken about the main catalyst. As of the conclusion of the 2018 season, 392 Venezuelans had played in the major leagues, with almost two-thirds of them reaching the “Big Show” after Pérez’s debut. While Vizquel, Andrés “The Big Cat” Galarraga, Díaz, Aparicio, and Chico Carrasquel reached the baseball pinnacle before Pérez, younger stars like José Altuve and Miguel Cabrera have followed in his footsteps. In the spring of 2017, Pérez beckoned the call of the motherland by serving as the bench coach for the Venezuelan team in the World Baseball Classic.

“There’ll be lots more (Venezuelan players) due to the (political) situation. Before, one could be doing OK with a college education especially in the oil industry. Fandom has always been there, people love baseball. It was easier for us to make a living, especially in the West, all of life’s necessities.” As Pérez and the author spoke on the phone in early 2019, the United States and dozens of other countries had recognized Juan Guaidó as the legitimate president of Venezuela, triggering a showdown with Nicolás Maduro.

Pérez’s catching exploits emboldened Victor Martínez and Salvador Pérez, perennial All-Stars at the position. At the end of the 2018 season, Pérez’s career placed him 11th among Venezuelan catchers in games played. Ever humble, he downplayed his role in fomenting the boom of his countrymen in the major leagues. Of the 10 players above him, only one — Díaz — debuted before Pérez. While playing for the Indians in 2002, Pérez mentored Martínez, a decade younger and still unpolished behind the plate. Pérez recalled telling Indians skipper Charlie Manuel, “V-Mart will be your top catcher” and Martínez himself, “I am not a fraction of the player you will be.” But above all, he credited Díaz, who “opened the doors with the great job he did, may he rest in peace.”

As Venezuela’s economy has collapsed, the possibility of a middle-class life has all but disappeared. Inflation reached one million percent in 2018, rendering the bolívar almost worthless and forcing those with means to subsist by turning to the black market for their needs.19 Players who fail to reach the majors may not have a good education as a backup plan. Though Pérez wished the younger generation the best of luck, he said he was deeply concerned about the underlying conditions: “Some schools have 12- to 14-year-olds with poor education. Education has worsened for the younger generation; the baseball schools don’t cover education.”

Pérez garnered another milestone in 2014 as he became an American citizen, cementing his ties to the Atlanta area and the franchise that has employed him for almost three decades.20 Prior to the 2019 season, Pérez was named a special adviser for player development, granting him oversight of the next generation Braves while they make their way through the system.21

From his new perch, Pérez hoped to counsel not just the Braves’ farmhands but also the system within the major leagues. “Working with the Braves, I am focused on ensuring they don’t just play well but also learn English. … We’ll soon pass the Dominicans (in percentage of major-league players). Venezuelan players seek that better future, just like Dominicans did. There will be lots of great players, representing Latin America and Venezuela, but it saddens me to see the younger players struggle to read. (The major leagues) must do a better job.”

Acknowledgments

- Eddie Pérez for graciously discussing his career via a phone interview.

- Greg McMichael, Atlanta Braves director of alumni relations, for connecting the author to Eddie Pérez.

- JJ Montilla, Venezuelan sportswriter, for sharing the Venezuelan Baseball reference site Pelota Binaria, which includes winter league statistics.

- Pete Palmer and Jim Wheeler for detailed disabled-list records.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author relied extensively on Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 brainyquote.com/authors/johnny_bench.

2 Eddie Pérez, telephone interview, January 29, 2019. Unless otherwise indicated, all quotations directly attributed to Pérez come from this interview.

3 Robert Lohrer, “Broward Loses Big League Title,” South Florida Sentinel (Fort Lauderdale), August 17, 1986. sun-sentinel.com/news/fl-xpm-1986-08-17-8602180967-story.html.

4 govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GOVPUB-T63_100-dd1437db9d97161a1d6cd2945151dd6c/pdf/GOVPUB-T63_100-dd1437db9d97161a1d6cd2945151dd6c.pdf.

5 govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GOVPUB-T63_100-dd1437db9d97161a1d6cd2945151dd6c/pdf/GOVPUB-T63_100-dd1437db9d97161a1d6cd2945151dd6c.pdf.

6 As of the conclusion of the 2018 season: baseball-almanac.com/feats/feats5.shtml.

7 Associated Press, “ Braves’ Perez May Miss Season,” New York Times, March 22, 2001. nytimes.com/2001/03/22/sports/plus-baseball-braves-perez-may-miss-season.html.

8 Tom Ley, “Here’s an Awesome Story About Greg Maddux,” Deadspin.com, January 8, 2014. deadspin.com/heres-an-awesome-story-about-greg-maddux-1497441759.

9 Rob Neyer, Rob Neyer’s Big Book of Baseball Legends: The Truth, the Lies, and Everything Else (New York: Touchstone, 2008), 14-16.

10 pelotabinaria.com.ve/beisbol/temporadas.php?TE=1994-95.

11 pelotabinaria.com.ve/beisbol/mostrar.php?ID=pereedu002.

12 pelotabinaria.com.ve/beisbol/mostrar.php?ID=concdav001.

13 Mark Bowman, “Perez Eyeing Venezuelan Winter League Title,” MLB.com, January 21, 2016. mlb.com/braves/news/braves-eddie-perez-eyeing-winter-league-title/c-162485118.

14Mike Axisa, “MLB’s Biggest Problem Is Not Pace of Play and It’s Only Getting Worse in 2018,” CBSSports.com, April 15, 2018. cbssports.com/mlb/news/mlbs-biggest-problem-is-not-pace-of-play-and-its-only-getting-worse-in-2018/.

15 Jim Albert, “Historical Look at Pitcher Usage,” January 28, 2019. baseballwithr.wordpress.com/2019/01/28/historical-look-at-pitcher-usage/.

16 atlanta.braves.mlb.com/team/coach_staff_bio.jsp?c_id=atl&coachorstaffid=120407.

17 David O’Brien, “Eddie Perez’s Son Drafted by Braves in 36th Round,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, June 11, 2016. ajc.com/sports/baseball/eddie-perez-son-drafted-braves-36th-round/PaN3SAsQzLVtLzgKdpMTYL/.

18 ungathletics.com/roster.aspx?rp_id=3060.

19 Reuters, “IMF Projects Venezuela Inflation Will Hit 1,000,000 Percent in 2018,” Reuters.com, July 23, 2018. reuters.com/article/us-venezuela-economy/imf-projects-venezuela-inflation-will-hit-1000000-percent-in-2018-idUSKBN1KD2L9.

20 Michael Cunningham, “Braves Coach Perez Becomes American Citizen” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, August 14, 2014. ajc.com/sports/braves-coach-perez-becomes-american-citizen/YvxtkUA6bXj9L4A9MaO6LJ/.

Full Name

Eduardo Rafael Perez

Born

May 4, 1968 at Ciudad Ojeda, Zulia (Venezuela)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.