Omar Vizquel

Venezuela has been a cradle of shortstops since 1950, when Alfonso “Chico” Carrasquel made his debut in the majors with the Chicago White Sox.

In his steps followed Luis Aparicio, the only Venezuelan in the Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, Dave Concepción, Ozzie Guillén, and then another shortstop who played more games at that position than at any other in the majors: Omar Enrique (González) Vizquel.

Vizquel was born in Caracas on April 24, 1967, to Omar Santos Vizquel and Eucaris González, the eldest of three children. He has a younger brother, Carlos Alberto (born 1970), and Gabriela (1980).

“My dad was an electrician in Caracas. My mother was a woman of the household, enterprising, with a very strong character,” Vizquel remembered. “We are a very close family, very quiet.”1

“I grew up in a neighborhood called Bloques de Santa Eduvigis. That is the height of Palos Grandes, in Caracas. There I attended the Santa Gema School for two years, and then we moved to a neighborhood called El Cafetal, where I attended the Josefa Irausquín López School. There I spent most of my school until I graduated and went to Antonio López Méndez School,” he recalled. “I ended up graduating in Francisco Espejo College, in El Cafetal. That was the year I received an offer to sign a professional baseball contract. … so I did not attend my graduation party but traveled directly to the United States, after I finished the school year, in 1984.”

His love for baseball was instilled by his father, who passed away in 2016.

“My dad played on an amateur team and took me to the games on weekends. That began to motivate me, and I grew to love the game. I was given a Venezuelan brand Tamanaco baseball glove, blue, that was one of my favorites, and with that I started playing baseball to follow the footsteps of my father.”

He played baseball in his spare time. “All my friends always invited me to play and I was very happy at Santa Eduvigis blocks with all those friends playing with balls that we (made) with adhesive tape and guava sticks that we used as a bat.”

When he was 8, Omar’s father took him to the Lyceum Gustavo Herrera to join a children’s team, Gran Mariscal, of the Leoncio Martinez League, an affiliate of the Criollitos of Venezuela Corporation, a youth movement similar to the Little League organization.

“The coach put me to play shortstop and I was on that team until I was 16 years old.”

With Gran Mariscal, Vizquel developed his skills and managed to represent Miranda state in several national and international tournaments, along with another future big-leaguer, Carlos Hernández, who caught for the Los Angeles Dodgers.

In 1977, in a Little League Baseball World Series, contested by 12 countries at Universitario Stadium in Caracas, Vizquel’s glove work began winning him fans and was instrumental in Venezuela’s winning the title. He was only 10 years old.

“At that age you do not feel that you are famous or anything. You are simply playing sports, and not looking to see if you are in newspapers or anything like that,” he said. “But the organizers noticed, and when you went to a national or other World Series, your name would stand out. Two years after that World Series, I went to a national tournament, where I won the award for the best infielder. Every two years I was going to a National and I represented Miranda state a couple of times, and I won the best infielder award, and I was invited to numerous competitions.”

These tournaments were played in one of the stadiums of the Venezuelan professional baseball league before winter league games, so Vizquel had the opportunity to meet some of his predecessors, Chico Carrasquel, Aparicio, and Concepción, his main idol and the starting shortstop for the Cincinnati Reds, who also played in Venezuela with Tigres de Aragua.

“We did not go often to the stadium to watch the winter ballgames, just when Dave Concepción was going to play with Tigres de Aragua. My dad, who was a big fan of Dave Concepción, took me to see him play and we sat in the third-base stands to see him play ball,” he recalled. “I really liked his style and I followed in his career when he was with the Cincinnati Reds. That’s why I wore the famous number 13 in my career, in honor of Dave Concepción.”

The shortstop of the Big Red Machine was a big influence and motivation to Vizquel when he decided to pursue the dream of becoming a professional baseball player.

“When I was 14, I knew I had skills to play the sport, and this was actually when I started to get serious with baseball. Back then I worshipped Dave Concepción. I followed his games, was more aware of the details of how he made a double play, how he fielded a grounder, to get the right position when fielding, all these little things that could help me to develop my own game. I also went to a clinic that Alfonso Carrasquel gave and I began attending activities that had to do with baseball to learn a little bit more about it.”

One of his teammates on the Gran Mariscal team was Luis Morales, son of Pablo Morales Chirinos, one of the owners of Leones del Caracas, the Venezuelan Winter League team to which he was invited to attend practices at age 16.

“When I went to train with Leones del Caracas, I met Marty Martínez that afternoon, a scout for the Seattle Mariners. In two days I had signed a contract. I was very lucky, because there were players who were training three to four months and had not been offered a contract. But with me it was different. I had just two days’ training and Marty had offered me a contract to go play with the Mariners. I was very lucky.”

Vizquel signed as a free agent with a non-guaranteed bonus of $4,500, in 1984. He received $2,500 up-front with the rest to come in installments of $500 at each step up the ladder.

He immediately went to America and played Rookie League ball with the Butte Copper Kings; he hit for a .311 average in 15 games.

“The minor-league process was normal. Every year I had the opportunity to move to a different league. I started in rookie league, because I was 16, and then I was promoted to Class-A short-season ball (1985 Bellingham Mariners), then to Class A (1986, Wausau Timbers), and then switched to Class A Advanced (1987, Salinas Spurs). At each level, I was able to develop further.”

His participation in winter ball with Leones del Caracas also helped him mature as a player and to better develop his skills.

“When I was in Class A I was added to the roster of Leones del Caracas, playing as a 19-year-old with players from Double A and Triple A. When I got to Double A, I got the chance to play as a starting shortstop in Venezuela and I think that made me a much faster player, because I was already playing with major-league players. I remember that Andrés Galarraga was the first baseman, Baudilio “Bo” Díaz was catching, Antonio “Tony” Armas was one of the outfielders, along with Lloyd McClendon and Donell Nixon; Jesús Alfaro was at third base and Edgar Cáceres at second. I was the youngest guy and I had the nickname ‘Chamo Menudo,’ because the youth music group Menudo was the band of the moment.”

That experience helped Vizquel on his journey through Double-A (Vermont Mariners) and Triple-A (Calgary Cannons), in 1988, when he became a switch-hitter on the recommendation of Mariners hitting instructor Bobby Tolan.

“In 1988 they took me to the Instructional League to learn to bat left-handed, because they saw that my right-side numbers were a little weak. They thought that batting lefty I could exploit a little more speed and batting skills; it was a change that benefited me a lot and maybe was the key to success for me in the big leagues.”

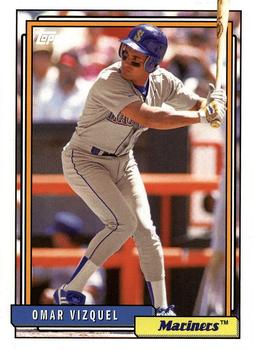

During 1989 spring training the Mariners had Rey Quiñones as first-string shortstop, but he reported late because of a contract dispute, which began to open the doors of the majors to the young Venezuelan shortstop.

“Supposedly that year I had to go to Triple-A, but with Quiñones out, Mario Díaz had to play,” Vizquel recalled. “He was the shortstop in Triple-A and had good numbers, but was injured during spring training and there was nobody else to play shortstop so they threw me into the ring to see what I could do and I surprised the manager, Jim Lefebvre.”

Díaz injured his right elbow and Vizquel had the opportunity to display his defensive talents, and he impressed Lefebvre, despite his weaknesses as a batter.

“He liked the way I played, how I defended, and he knew I was learning to bat from the left side that year, but I knew it was going to get difficult to stay in the big leagues, but they made the decision, traded Rey Quiñones to the Pirates, and left Mario Díaz as the utility player, because he continued to suffer arm problems. That left me as the shortstop.”

At just 21 years old, a few days shy of 22, Vizquel received the news on the last day of spring training.

“I had to ask one of the coaches, ‘What do I do with my bags? Am I going to Triple-A? Am I going to be in the big leagues? I need to know, because people are packing,’” he recalled. “I was not told I was going to be the team’s shortstop until the last day of spring training. After the final out, they gave me the news. It was a total surprise because the last thing I thought was that I was staying in the majors that year.”

Vizquel’s debut came on Opening Day, April 3, 1989, at the Oakland Coliseum, facing the reigning American League champions, the Oakland Athletics. Vizquel was not the only rookie debuting in Lefebvre’s lineup. So was Ken Griffey Jr., from the start a media sensation.

Vizquel did not make the best of impressions in his debut, with a fielding error on Carney Lansford’s roller in the third inning, followed by a Mark McGwire home run, which made all the difference in the A’s 3-2 win over the Mariners.

“I felt bad for the error, but I never felt that I was going to be affected by it in the future. They had already given me the confidence to go out and play my game. The manager told me, ‘We know you’re not ready for this kind of work, but we like the way you play and you will be our regular shortstop.’”

Vizquel’s first campaign was not his most productive. He finished with a .220 batting average, the lowest of his career, but he learned how to handle the pressure of playing as a shortstop in major-league baseball.

Vizquel’s first campaign was not his most productive. He finished with a .220 batting average, the lowest of his career, but he learned how to handle the pressure of playing as a shortstop in major-league baseball.

“I had many things against me. First, I was learning to bat from the left side; it was not going to be easy to learn to bat left-handed against big-league pitchers. The Mariners knew that I wasn’t really ready to play in the majors, but I got the job and they gave me the opportunity. By asking questions, and working all day every day with the guys who were there, like Alvin Davis, Harold Reynolds, who were regulars in the organization, learning the little things they were always telling me — how to bat from the left side, it all helped me gradually to become a better player.”

Vizquel began the 1990 season on the disabled list after suffering a sprained MCL in the left knee; he played in only 81 games, batting .247 and making seven errors. He played 142 games in 1992; his batting average slipped to .230. Nevertheless, Seattle remained confident in his abilities.

“Obviously the bat was not the reason that I was in the majors. That’s for sure. It was the way I played and my glove,” he said. “The glove was my best asset, and I could steal some bases, could play the ball, could do hit-and-run. Those are the things that you try to instill in young boys today who expect to reach the majors just hitting all the time. There are other things you have in your repertoire that you can develop, and you can stay in the majors doing small things. That was my case.”

By 1992 Vizquel was considered one of the best defensive shortstops in the American League. That season he made only seven errors for a .989 fielding percentage, the best in the majors. For the first time he was a candidate for the Gold Glove Award, though Cal Ripken Jr. got the nod.

“I was very pleased with the work I had done, so was the organization, and that was all that interested me,” said Vizquel, who hit a strong .294 that season. “I was improving my game in both batting and fielding.”

His reward came the following year, when he turned 108 double plays, tied for the league lead. His fielding percentage of .980 and the growing appreciation of his talent combined to win him his first Gold Glove. One standout moment occurred on April 22, when he preserved Chris Bosio’s no-hitter against the Red Sox by making a barehanded grab of an Ernest Riles chopper and firing to first for the last out of the game.

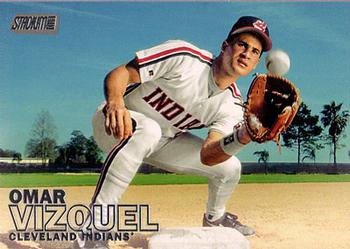

Vizquel felt settled in Seattle, where he took up residence and married his first wife, Nicole Tonkin, but his plans changed when he was surprised with the news that he had been sent to the Cleveland Indians on December 20, 1993, in a trade for Félix Fermín, Reggie Jefferson, and cash. The Mariners were making room for a talented youngster named Alex Rodríguez.

“When I got the news that they traded me to Cleveland I felt pretty bad. I was down. I wanted to be on a team for 20 years. I did not want to move anywhere else,” he said. “I felt good with the Mariners. I had married that year, had bought my house. It was like they gave me a slap in the face, and I had to move to another organization where I knew no one.

“The first time you are traded you think about a lot of things. The first is that the team does not like you, that they trade you because they don’t like what you’re doing. But I took it otherwise. I took it the positive side. When I got to spring training and met the players and the kind of talent that the team had, I felt much better and I clicked very well on that team. With all the Latin players there, I had a very good time that year with the Cleveland Indians.”

Vizquel joined a group of Latinos who helped the Indians change their image from that of a perennial loser, which was satirized in the 1989 movie Major League. The Indians had put together a very competitive club in 1994 with Manny Ramírez, Carlos Baerga, Sandy Alomar Jr., Tony Peña, Dennis Martínez, José Mesa, Julián Tavárez, Álvaro Espinoza, Rubén Amaro Jr., and Candy Maldonado.

That group, together with Kenny Lofton, Albert Belle, Jim Thome, Eddie Murray, Charles Nagy, and Jack Morris, helped the Indians to a 66-47 mark, just a game behind the Chicago White Sox for the American League Central lead when the season was suspended because of the players’ strike.

“You could tell that team was coming together well,” Vizquel said. “We had good chemistry and everyone was filled with confidence. The team chemistry was growing and we thought we had a chance to be champions that year; however the strike prevented us finishing the season.”

Vizquel, who on April 7 that year got the first stolen base in the history of Jacobs Field, the Indians’ new home ballpark, won the second of nine consecutive Gold Gloves in the American League.

There was no strike to stop the 1995 Indians, who were reinforced by veterans like Orel Hershiser and Dave Winfield, and reached their first World Series since 1954.

“In 1995 we felt like we were indestructible,” Vizquel said. “We felt that no one could beat us. We had offense, pitching, we ran bases. We had a great team. I was very happy that we finally got to where any player wants to go: the World Series.”

The Tribe swept the Red Sox in three games in the Division Series and dispatched the Seattle Mariners in six games in the American League Championship Series, after having 100 victories in a regular season limited to 144 games by the delayed start of the season.

“With this record we looked unbeatable. I never thought we were going to lose, even with the pitching of the Atlanta Braves, but certainly we lacked experience,” he said. “I think that was the only thing we lacked; the Braves had a team with more postseason experience.”

The Braves, with Bobby Cox as manager, had reached the fall classic in 1991 and 1992, but in 1995 their pitching looked even better with Greg Maddux, Tom Glavine, and John Smoltz, all future Hall of Famers.

“We were like wild horses. What we did was just play ball, score runs, stole bases, and they played a different style of baseball, pitching around,” said Vizquel, who in his first postseason hit just .138. “They could score two runs and win a game with their relievers. That was what happened. We couldn’t hit. Their pitching was dominant. With these three future Hall of Famers (Maddux, Glavine, and Smoltz) it was difficult for us to see the light and we lost that World Series.”

In 1997 Vizquel returned to the fall classic with the Indians after playing a key role in eliminating the defending champion New York Yankees in five games in the ALDS.

In 1997 Vizquel returned to the fall classic with the Indians after playing a key role in eliminating the defending champion New York Yankees in five games in the ALDS.

With the Yankees ahead in the series, two games to one, Vizquel forced a fifth and deciding game at Jacobs Field, hitting a single that drove in Marquis Grissom from second base in a 3-2 walk-off victory. The Tribe won the next day, 4-3. Vizquel ended the series with a .500 (9-for-18) batting average and four stolen bases.

In the ALCS the Indians had their revenge on the Baltimore Orioles, who had eliminated them in 1996, and beat them in six games to advance to the World Series against the Florida Marlins.

“We thought we had more experience than the Marlins. It was a fairly new team, which came almost all from different teams, and we thought we could win.”

Vizquel was never closer to winning a World Series ring than that year and again was a key to forcing a decisive contest, Game Six of the Series.

The Marlins led the Series three games to two. In Game Six at Miami’s Pro Player Stadium, Cleveland had a 4-1 lead after five innings, due in large part to Vizquel’s glove. In the sixth inning, with men on second and third and two outs, the Marlins’ Charles Johnson hit a grounder in the hole and Vizquel made a spectacular diving catch to throw him out at first and prevent two runs from scoring.

“Everyone in Cleveland will remember that play, because of the magnitude of the moment. World Series plays are special moments,” he said. “It was the biggest play of my career. Logically the moment marked that play. When I talk about the Seattle Mariners, people always remember the play in Chris Bosio’s no-hitter. If I had to pick one play, it would be the World Series one, but if you talk about Omar Vizquel the infielder, people always remember the barehanded plays because I made it very often and it’s like a brand, the dude grasping a ball without a glove. I’m also recognized by that.”

In the deciding Game Seven, with Cleveland two outs away from winning the ultimate prize, the Marlins tied the game in the ninth inning and then won it, 3-2, in 11 innings on Edgar Renteria’s walk-off hit.

“We went to Game Seven and couldn’t achieve the ultimate victory. It was a game that went to extra innings and in extra innings anything can happen,” Vizquel said. “I think that the beauty of this Series was going to Game Seven. It’s like a dream that everybody has: Play the seventh game of the World Series. There is no further, everyone is watching the game, and everything is magnified three times. The challenge to be there playing and trying to do your best for your team was one of the things that has filled me as a player. Knowing that I could handle that moment, because not everyone can handle that kind of pressure, made me feel very good about myself.”

In 2001, Vizquel won his ninth Gold Glove, matching the American League record held by Hall of Famer Luis Aparicio. He also played in his last postseason. The golden years of the Tribe were over. Only Vizquel and Jim Thome remained from the winning core that had been formed in the mid-’90s. Thome left as a free agent after the 2002 season, in which Vizquel set career highs in home runs (14) and RBIs (72), and took part in his third and final All-Star Game, being the sole representative of the Tribe.

The Indians were rebuilding in 2003 and Vizquel, with an injured right knee, played in just 64 games. In 2004, at the age of 37, he returned with a solid .291 average, but the Indians had other plans for 2005 and gave the position to rookie Jhonny Peralta.

“Everybody had already left the team. I was the last that remained of that generation that made the playoffs, the World Series,” Vizquel noted. “That’s why the people of Cleveland showed me so much affection. But this is a business. I was fortunate that I lasted 11 years in the organization. They treated me great, and I will always take pride in those years.”

On November 16, 2004, Vizquel signed a three-year, $12.25 million deal with the San Francisco Giants, moving his magic glove and experience to the National League.

“I knew I still had a lot of baseball ahead. (The Indians) believed that I was going downhill. The knee operation affected me and I think that influenced their decision to let me go. When San Francisco signed me, thank God I made it to a number-one organization, one where I felt good, was offered all possible respect, and could even trust myself. That helped me win two more Gold Gloves at the age of 38 and 39 years.”

In 2005 Vizquel had a brilliant debut in the Bay Area, winning his 10th Gold Glove to surpass Luis Aparicio’s record for the most Gold Gloves won by a Venezuelan. The following year he repeated the honor and became the oldest shortstop to obtain the distinction.

On May 13, 2007, Vizquel broke the record for most career double plays turned by a shortstop after reaching 1,591, surpassing the 1,590 of Ozzie Smith. His years as a regular shortstop ended the following season, but not until after he established a major-league record for most games for a shortstop with 2,584, surpassing another mark held by Luis Aparicio. When he retired, Vizquel’s career total at shortstop was 2,709.

He maintained his physical condition at the highest level, despite his 41 years, but clubs were not very interested in giving him a starting spot. He was seen as a utility player and mentor of young figures, like fellow Venezuelan Elvis Andrus when Vizquel went to the Texas Rangers in 2009.

“I think he was very helpful for me,” Andrus said of Vizquel. “And I imagine, putting myself in his shoes, it’s hard to play your whole career as a starter and have to change to the role he had here, as a substitute, or as my mentor, actually. He helped me a lot and I feel super blessed. Having him in my first year in the big leagues was like having a bible of how to do things, how to play baseball, how to prepare to play. Mentally I think Omar is one of the best shortstops in the whole story and I think that he helped me very much since day one. He always gave me advice and helped me, especially during the bad times I had that year to keep focused on the positive things and never let the negative consume me. These were tips that I continue to use to this day.”2

Vizquel added, “It was strange to play after turning 40 and hear the comments of people saying I couldn’t keep playing baseball. They were wondering if I could be a shortstop, because a 40-year-old shortstop is not the same as a 24-year-old kid in an organization. That boy is going to be as versatile as you, but they never took into account the experience, or anything like that,” he said. “It was a stage, in which the mind began to change, to see the game different, with another vision, and I had to make changes, adjustments in every sense of the word, and thank God they were noticing some of the records I was setting and they offered me the opportunity to reach these personal records.”3

In his one year with Texas he played only 62 games and made no errors, having his only perfect defensive year. On June 25, in Arizona, he surpassed Aparicio as the Venezuelan with the most major-league base hits, with 2,678.

In 2010 Aparicio graciously allowed Vizquel to wear his retired No. 11 jersey with the Chicago White Sox, after the newly acquired utilityman failed to secure his usual number 13 — that was worn by his new manager Ozzie Guillen, who was also a Dave Concepcion fan.

“That was a truly enjoyable time, because at the time I signed with the White Sox, I was giving a baseball clinic with Luis Aparicio in Venezuela, and the question came up whether I could wear #11 in tribute to him,” Vizquel said. “It was a nice gesture from him to call the owners of the White Sox and let me wear the number not only in his name but on behalf of Venezuela as well.”4

In 2012 he signed a minor-league contract with the Toronto Blue Jays and managed to make the team in spring training. This time he wore number 17, in honor of Chico Carrasquel, because Brett Lawrie had number 13. He participated in 60 games, his last game at shortstop coming on October 3 in Toronto. In his final game, he went 1-for-3 against the Minnesota Twins, getting his 2,877th hit and passing Mel Ott on the career hits list. (Two weeks earlier, on September 19, he had collected hit number 2,874, passing Babe Ruth.) He finished his career as the only player with 24 straight seasons at shortstop and, at age 45, the oldest player to play that position.

Just other five major-league shortstops have more career hits than Vizquel: Derek Jeter, Honus Wagner, Cal Ripken Jr., Robin Yount, and Alex Rodríguez, all with over 3,000.

“I think the hits record makes me proud the most. People believe that is the Gold Gloves one, a record hard to achieve as well. Winning 11 Gold Gloves is not easy at the highest level of baseball, but to connect for 2,800 hits, nearly 3,000, is something especially since I had never been considered a hitter.”

Vizquel finished with a career line of .272/.336/.352, with 456 doubles, 77 triples, 80 home runs, 1,445 runs, 951 RBIs, and 404 steals, and he is one of just 11 players to accomplish 2.800 hits and 400 stolen bases. But his trademark was his fielding excellence.

The Venezuelan finished his career with a .9847 fielding percentage, the best in MLB history, just above Troy Tulowitzki (.9846) as of 2018. He the leader in games (2,709) and double plays (1,734) as a shortstop, and ranks third in assists (7,676). His 11 Gold Gloves ranked him second as a shortstop, just behind the 13 that the first-ballot Hall of Famer Ozzie Smith won, another glove wizard with whom he was often compared.

After 24 seasons playing in the majors, Vizquel decided to start a coaching career after spending his last four years mostly on the bench, as a utility player, passing his knowledge to young players while accumulating personal records when he got the chance to go to the field.

“I felt very happy that in each of those organizations in which I played I could break records that meant something beautiful for me on a personal level,” he said. “I did not play because I wanted to break those records, I just felt really good about myself and my knees were responding fully. I was a gym freak and able to maintain my body in good shape. Even after I retired with the Blue Jays, when I was in Anaheim, I had some regret that I’d retired because I felt I could continue playing, but I was ready to be a coach.”

On January 30, 2013, Vizquel was hired as a roving infield coach by the Los Angeles Angels. The next year he returned to the majors with the Detroit Tigers, who made him their first-base coach and infield and baserunning instructor. That association ended after the 2017 season.

“That’s something I had to do because I want to be a manager and that was one way of preparation, hearing all the comments from the coaches. Right now I love my job. The fact that I can help a boy to develop his game pleased me very much.”

Vizquel, who was a candidate to manage the Tigers in 2018 (Ron Gardenhire was hired), got his first managerial experience with Venezuela in the 2017 World Baseball Classic, but his team couldn’t pass the second round.

“The WBC was spectacular. Although we didn’t reach the final goal, which was to reach the last playoff, we were able to sneak into the second round. It was a shame we did not score the necessary runs and that the pitching dropped a little bit, because in a short competition anything can happen,” Vizquel said. “As a first experience as a manager, I had a great time.”

Vizquel came back to the White Sox organization in 2018 as the manager of their Class-A affiliate at Winston-Salem. He still resided in Seattle as of 2018, along with Blanca Garcia, his wife since 2014. They live near his two children, Nicholas, born in 1995, and Kaylee, who was adopted in 2007.

Vizquel was inducted into the Cleveland Indians Hall of Fame on June 21, 2014, and was chosen by the fans as one of the Tribe’s Franchise Four in 2015, alongside Bob Feller, Tris Speaker and Thome.

Vizquel had his first shot at election to the Hall of Fame in 2018, when Chipper Jones, Vladimir Guerrero, Jim Thome, and Trevor Hoffman got the call, but he fell short with 37 percent of the votes.

“I’m very happy,” he said. “When you are first eligible for the Hall of Fame you do not know what kind of support you will receive from the voters. As time goes by you can increase or you can stay in the same position. I believe that it will continue to increase, although in the sabermetrics there are numbers that do not benefit me, but who saw me playing ball knows the game, knows what I did, knows my skills, what I was able to do and that (is) not numbers. You work for that on the field and the rest is on the part of the voters to discuss it.”

Nevertheless, his debut on the ballot was better than that of Aparicio, who finished with 27.8 percent in his first chance and finally made in his sixth opportunity.

“I hope he gets into the Hall of Fame, because he deserves it, but I think the change of position (from shortstop) is going to hurt him,” said Aparicio. “It also depends on who else is on the ballots, but I think he’s going to make it. I think about the shortstops that I saw and there is none like that little fellow, because he fields grounders like nobody else.”5

“You flip back and see how time flew,” Vizquel said. “Playing 24 seasons in the majors and having all those memories, records, and stats make me feel very humble. I never thought I could go up to the heights of a player like Luis Aparicio and get to have so many good numbers.”

Last revised: November 12, 2018

This biography was published in “1995 Cleveland Indians: The Sleeping Giant Awakes” (SABR, 2019), edited by Joseph Wancho.

Sources

baseballhall.org/hof/2018-bbwaa-ballot.

cbssports.com/mlb/news/2018-baseball-hall-of-fame-ballot-the-cases-for-and-against-omar-vizquel/.

cleveland.com/tribe/index.ssf/2018/01/path_to_cooperstown_will_not_b.html.

espn.co.uk/mlb/news/story?id=3419650.

mlb.com/es/news/tiene-autenticos-argumentos-omar-vizquel-para-el-salon-de-la-fama/c-262497102.

Vizquel, Omar, and Bob Dyer. Omar! My Life on and Off the Field (Cleveland: Gray & Company, Publishers, 2002).

Cárdenas Lares, Carlos Daniel. Venezolanos en las Grandes Ligas (Fundación Cárdenas Lares, 1994).

Various Authors. Todo lo que usted debe saber sobre Omar Vizquel (Grupo Editorial Macpecri, 2012).

Notes

1 Author interview with Omar Vizquel on January, 7, 2015. Unless otherwise noted, all comments by Vizquel are from this interview.

2 Author interview with Elvis Andrus on March, 10, 2018. Unless otherwise noted, all comments by Andrus are from this interview.

3 Author interview with Vizquel.

4 Ibid.

5 Luis Aparicio and Augusto Cárdenas, “Mi Historia: Luis Aparicio,” 2011.

Full Name

Omar Enrique Vizquel Gonzalez

Born

April 24, 1967 at Caracas, Distrito Federal (Venezuela)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.