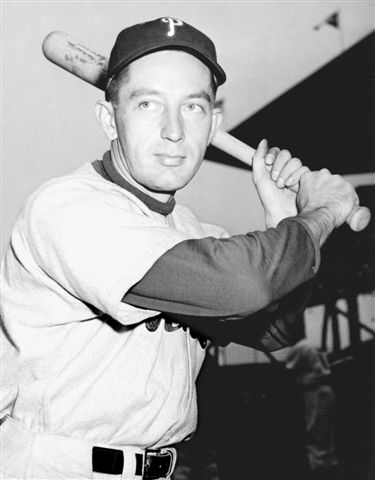

Eddie Waitkus

Eddie Waitkus was a slick-fielding first baseman who in an 11-year big-league career for three teams batted a solid .285 and struck out only 204 times in 4,681 plate appearances. Although a fine ballplayer, he would today likely be little remembered but for what happened to him on June 14, 1949, in a room at the Edgewater Beach Hotel in Chicago. That evening a young, obsessed female fan named Ruth Steinhagen lured Waitkus to her hotel room with a cryptic note and then shot him in the chest, critically wounding him.

The Waitkus shooting is said to have inspired Bernard Malamud to write his iconic baseball novel, The Natural, which he published in 1952 and which was later immortalized in the Robert Redford movie by the same name in 1984.1

Waitkus managed to survive the shooting after enduring four operations, and returned to the major leagues in 1950, playing a key role in the Philadelphia Philles Whiz Kids’ rush to the National League pennant. But the story does not have a happy ending. Waitkus was never really able to recover emotionally from the shooting, and his post-baseball career was particularly difficult. He battled depression and alcoholism and endured a nervous breakdown before succumbing to cancer just after his 53rd birthday.

Life began for Eddie Waitkus on September 4, 1919, in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He was born to Veronica and Stephen Waitkus, Lithuanian immigrants who met and fell in love on their passage to America. Eddie grew up, with younger sister Stella, in a modest flat in East Cambridge. He first learned to play baseball at Cambridge Field, a neighborhood park just a block from his home. He was a natural right-hander and liked to pitch, but didn’t have a glove, so he first played bare-handed.2

When Eddie was 8, his father, a butcher by trade who was an accomplished swimmer but knew nothing about baseball, brought home a first baseman’s glove for his son. Young Eddie was thrilled but didn’t have the heart to tell his father that he was a pitcher, not a first baseman, and that the glove was for a left-handed thrower. Instead, he just taught himself how to throw left-handed and became a first baseman.3

At Cambridge Field, Waitkus came under the tutelage of Jack Burns, who played first base in the big leagues for seven years with the St. Louis Browns and Detroit Tigers. Burns, whose big-league career was ending in 1936 just as Waitkus was preparing for his senior year of high school, taught Eddie the finer points of first-base play.4

Eddie’s life was to be full of hardships and the first occurred when he was only 14. His mother was hospitalized with pneumonia and died just days later.

Despite the tragedy, Waitkus went on to become an honor student at Cambridge Latin High, where he studied foreign languages, was a star debater, and graduated sixth in a class of 600. When he was a sophomore he walked into a baseball practice with his trusty first baseman’s mitt, only to be told by the coach that the team already had a first baseman. Eddie asked the coach to at least let him take a few grounders and after he scooped up everything hit his way, was told to grab a bat. Waitkus proceeded to smack line drives all over the park and all of a sudden Latin High had a new first baseman.5

By the time Waitkus graduated, he was a legend on the baseball field as well as in the classroom. He hit .600 his senior year, including a prodigious home-run blast that landed on the top of a three-story apartment building beyond the right-field fence. He was named to every All-Scholastic team in the Boston area in 1937 and that summer played in the semipro Suburban Twilight League. He considered accepting a scholarship to play baseball at either Harvard, Holy Cross, or Duke but playing for the Worumbo Indians of Lisbon Falls, Maine, in the fast Maine League during the summer of 1938 changed any college plans.6

Waitkus played exceptionally well and became the top prospect in New England that summer. His club won the Maine championship and qualified for the National Baseball Congress tournament in Wichita, Kansas, where it won two games before being eliminated. Waitkus hit over .500 in Wichita and fielded flawlessly. After the young first baseman was named by major-league scouts to an All American semipro team, Boston sportswriter Fred Barry proved prescient when he wrote, “These big league ‘wise men’ viewed the left-handed batting and throwing of 19-year-old Waitkus and termed him a ‘natural.’”7

Ralph Wheeler, the high-school sports editor for the Boston Herald, had close ties with the Chicago Cubs and arranged for Waitkus to work out for Cubs manager Gabby Hartnett on Chicago’s last trip to Boston to play the Bees. That led to a contract and a $2,500 bonus from the Cubs, who assigned him to the Moline Plow Boys of the Class-B Three-I League for the 1939 season.8

Eddie got off to slow start at Moline, perhaps because he had never played night baseball before, and after eight weeks was hitting only .189. But then he hit his stride and finished with a .326 batting average and a dozen triples, making the league’s All-Star team while playing for a seventh-place team.

That performance earned Waitkus a promotion to the Tulsa Oilers of the Class-A Texas League for 1940. He adjusted to the faster league quite well, batting .303 in 162 games and leading the league in hits with 192. Dizzy Dean, who was trying to rehab a sore arm, spent much of the summer with the Oilers and roomed with Waitkus when the team was on the road. While it would seem that the 30-year-old Southern country boy Dean and the 20-year-old kid from Boston would have little in common, they became fast friends. In fact, Dean became one of Waitkus’s biggest supporters.

In 1941 the Cubs invited Eddie to Catalina Island for spring training, where Dean continued to sing his praises. Waitkus didn’t disappoint and made an impact that spring. When the season opened on April 15 in cold and windy Wrigley Field, he was the Cubs’ starting first baseman. Hitting second in the lineup, he slapped a single in four-at-bats and recorded 13 putouts at first base as the Cubs defeated the Pirates 7-4.

But both the Cubs and Waitkus struggled thereafter with the team settling in the second division and Eddie garnering only four singles in 21 at-bats in part-time duty for the first month of the season. In the middle of May, he was returned to Tulsa, where he finished the season, hitting .293 in 125 games.

As a result of that solid performance, the Cubs assigned Waitkus to the Los Angeles Angels of the Pacific Coast League for 1942. This time he didn’t miss a beat stepping up to tougher competition and in 175 games and 766 plate appearances he batted .336 to finish near the top of the league in batting average. In fact, he led the league with 235 hits for the season. In spite of that, the year ended on a sour note as the Angels blew a four-game lead over the Sacramento Solons in the last five days of the season to finish in second place by a game. Waitkus, the team’s leading hitter all summer, slumped as well, failing to drive in a run in the season-ending series.9

During his year with the Angels, Waitkus got a taste of Hollywood, appearing in several action scenes batting and at first base during the filming of Pride of the Yankees. Apparently the movie’s producers thought that his swing and fielding more resembled Lou Gehrig’s than did Gary Cooper’s.10

One would normally expect that Waitkus would be back in Catalina Island with the Cubs in 1943. World War II, however, intervened, as it did for so many, and Eddie spent that spring in Army basic training in Fort Devens, Massachusetts. He was assigned to the 544th Engineering Boat and Shore Regiment and on May 2, 1944, shipped overseas from San Francisco to Oro Bay, New Guinea. Over the next 17 months Waitkus would see heavy combat on New Guinea, Morotai, Bougainville, and Luzon.11 He survived bloody initial beach landings on Morotai, Bougainville, and the Phillippines, where he narrowly escaped being taken prisoner by the Japanese.12

After Manila was secured, Waitkus worked with his outfit to repair Rizal Stadium, which could hold up to 30,000 GIs. After the booby-traps and a corpse were removed and foxholes and bomb craters were filled in, he and his mates played games in T-shirts, fatigues, and combat boots.13 Waitkus later remembered that soldiers from his unit wagered $60,000 against soldiers of the 594th Regiment for a game between the two.14 In September 1945, while the Cubs were winning the National League pennant, he and the rest of the 544th were among the first troops ashore at Wakayama, Japan.

Waitkus finished the war with 10 meritorious service awards, including four bronze stars and four overseas bars.15

Eddie was 26 years old when he reported to Catalina Island for the Cubs’ 1946 spring training after 34 months in the service. The only problem was that the Cubs had a first baseman, Phil Cavarretta, who was coming off a batting championship (.355) and a National League Most Valuable Player Award. When Waitkus arrived, manager Charlie Grimm, also a former slick-fielding first baseman, told him to go to first and take some groundballs. For a full 15 minutes Grimm futilely tried to smash a ball past Waitkus, but could not. Before long, the question was not whether Eddie would make the team, but when and where the team would move Cavarretta to make room for him at first base.16

Once the season began, Bill Nicholson, the Cubs’ right fielder, continued his slump from the previous year, and on April 25 manager Grimm benched Nicholson, moved Cavarretta to right field, and inserted Waitkus at first base. Batting sixth, Waitkus singled twice, doubled, and drove in two runs in his first game as a starter. Thereafter the job was his. By mid-June he was hitting .310 and fielding flawlessly. On June 23 Eddie got into the major-league record book when fellow rookie Marv Rickert and he hit back-to-back inside-the-park home runs in the Polo Grounds against the Giants. They were the first duo ever to accomplish the feat.

Waitkus finished the season with a .304 batting average, the only Cub regular to hit over .300, as the team slipped to third place, 14½ games behind the pennant-winning Cardinals. In 106 games at first base he committed only four errors for a .996 fielding average. The Chicago chapter of the Baseball Writers Association of America named him Rookie of the Year ahead of Del Ennis of the Phillies. He even finished 13th in the balloting for National League MVP, an unusual accolade for a rookie. According to Charlie Grimm, he was “easily the best all-round first sacker in our league.”17

Now entrenched as the Cubs’ first baseman, Waitkus battled injuries early in 1947, but when he was in there he still hit for a solid average, typically batting second in the batting order. He slumped in late May and early June, dropping to .244, but steadily improved his average the rest of the year. He had a big day at the plate on September 14 with a triple and two singles against the Boston Braves. For the season, he finished at .292 in 130 games, third best on a team that slipped to sixth place with a 69-85 record.

Waitkus and two other bachelors on the Cubs, Rickert and pitcher Russ Meyer, enjoyed the Chicago nightlife together since the Cubs played all day games at Wrigley. Eddie was known as a very sharp dresser whom the ladies much admired. Sometimes after dinner the threesome would go bowling or hit a nightclub. A favorite was the 5100 Club, where they would sometimes have ringside seats when comedian Danny Thomas performed.18

The Cubs continued their downward slide in 1948, finishing in the National League basement with a 64-90 record. It was hard to fault Waitkus, however, as he turned in another solid season, batting .295 in 139 games. He was even named to the National League All-Star team to back up starting first baseman Johnny Mize. Eddie walked in his only appearance, pinch-hitting for Johnny Sain in the sixth inning. Late in the season, Charlie Grimm, trying something new, even sent Waitkus to the outfield for 20 games. It was the only time in his career that he played a position other than first base.19

After the season the Cubs were on the trade market to try to resurrect the franchise, and found a willing partner in the sixth-place Philadelphia Phillies, who under new ownership were eager to turn their team into a contender. At the winter meetings in December, the two clubs announced a blockbuster trade with the Cubs sending Waitkus and pitcher Hank Borowy to the Phillies in exchange for pitchers Dutch Leonard and Walt Dubiel. Although trade rumors had Waitkus headed to the Giants or Dodgers, he was happy with the deal in part because he would be rejoining teammates Russ Meyer and Bill Nicholson, whom the Cubs had dealt to the Phillies earlier in the offseason.

Rogers Hornsby, the outspoken former Cubs manager, was not so thrilled. According to the Rajah, “The Cubs have two real ballplayers — Andy Pafko and Eddie Waitkus. They can’t trade the best first baseman in the business.” But of course they did and, as it turned out, the Phillies got a key component of their Whiz Kids club that would win the 1950 National League pennant.20

The slick-fielding Waitkus had an immediate impact on the longtime doormat Phillies in ’49 as the club flirted with the first division for much of the early season. By the first week of May, he was batting third in the order and hitting over .300. His teammates tabbed him “the Fred Astaire of first basemen,” and manager Eddie Sawyer compared him to George Sisler and Joe Kuhel, two of the top glove men of all time at first.21

Waitkus continued to enjoy the nightlife while with the Phillies, particularly with his old Cubs teammates Meyer and Nicholson, who was his roommate on the road. On June 14 the Phillies had just begun a 15-day road trip and had defeated the Cubs at Wrigley Field that afternoon, 9-2 behind Meyer’s complete-game pitching. Waitkus was enjoying his best year in the big leagues, hitting .306 and leading in the balloting for the All-Star Game.

That evening Waitkus went out for dinner and drinks with Nicholson and Meyer, Russ’s fiancée, Mary, and Meyer’s parents, visiting from nearby Peru, Illinois. After dinner, Nicholson and Waitkus took a cab separate from Meyer back to the Edgewater Beach Hotel, where the Phillies were staying.

When they arrived, Eddie suggested that Nicholson go down to the Beachwalk to find Meyer and ask him to join them for a nightcap. In the meantime, a bellhop approached Waitkus and told him that he had a note from a girl in his mailbox at the front desk. Eddie retrieved the note and read it while walking through the lobby. The writer identified herself as Ruth Anne Burns and gave her room number as 1297-A. She wrote, “It’s extremely important that I see you as soon as possible. We’re not acquainted but I have something of importance to speak to you about. I think it would be to your advantage to let me explain it to you.” The note concluded by saying, “Please come soon. I won’t take much of your time.”

Waitkus returned to the front desk and asked who was registered in room 1297-A. The clerk told him that the registration was to a Ruth Anne Burns from Portland Street in Boston. That information made Waitkus a little uneasy, as he had grown up on Portland Street in East Cambridge. Eddie decided that he should find Nicholson and Meyer for that drink and joined them at a small table at the back of the Beachwalk. He showed his teammates the strange note and finally decided he should call on Ruth Anne Burns, thinking she might be a family acquaintance who was in need of help.

He first called the room, and it seemed to him that Ruth Anne may have been asleep. But she urged him to come up and at about 11:30 he knocked on her room door. Ruth Ann opened the door and bade him come in. Waitkus entered the room and walked past her in the tiny room and sat down in a small armchair by the window.

The girl, who was in reality 19-year-old Ruth Ann Steinhagen of Chicago, appeared from behind the door brandishing a .22-caliber rifle and said, “I have a surprise for you. You are not going to bother me anymore.”

Waitkus stiffened immediately and said, “What goes on here? Is this some kind of joke? What have I done?”

She answered by shooting Waitkus once in the abdomen. As Eddie slumped down he said over and over, “Oh baby, why did you do that?”

Steinhagen at first wasn’t convinced she’d shot Waitkus, but eventually stepped over Eddie, returned the gun to the closet, and called the front desk, saying that she had just shot a man in her room.

That call probably saved Waitkus’s life. He was near death when he was taken to the Illinois Masonic Hospital. The bullet had pierced a lung and was lodged near his spine. He would undergo two operations at Masonic before being transferred to Billings Memorial Hospital on the University of Chicago campus, where he had a third operation. There he developed a persistent fever and it was determined that he needed a fourth operation to remove the bullet.

After being indicted for attempted murder, Ruth Ann Steinhagen was declared mentally ill and committed to the Kankakee State Hospital. She had been obsessed with Waitkus since she first saw him play for the Cubs in April of 1947. Although she had never met him, she attended all the Cubs games and would wait for him to pass by outside the clubhouse after the games. Her room was a virtual shrine to Waitkus and she ultimately decided that if she couldn’t have him, nobody could.22

Waitkus’s recovery was near miraculous. He spent a month in the hospital before returning to Philadelphia by air on July 17, where 500 fans braved the pouring rain to greet him. By early August the Phillies were in their worst slump of the season, having lost five games in a row and 10 of 13. Waitkus was restless convalescing in his Philadelphia apartment and, accompanied by Babe Alexander of the Phillies’ front office, flew to Pittsburgh, where the Phillies were playing the Pirates. He walked unannounced into the Phillies clubhouse, where his teammates were shocked at how much weight he had lost. But his visit must have helped because the Phillies beat the Pirates and began playing better.

On August 19 the club had a “Welcome, Eddie Waitkus” night at Shibe Park, where Waitkus was greeted with a standing ovation from nearly 20,000 fans. He wore his Phillies uniform, although his jersey hung loosely from his frame, and received a new Dodge convertible, a television set, golf clubs, a full wardrobe including about 10 suits, a two-week vacation to Atlantic City, and many other gifts. Dick Sisler, who had replaced Waitkus at first base, presented a tearful Eddie with a gift from the team, a bronzed first baseman’s glove and two silver baseballs mounted on a velvet-covered plaque. “You put me on the spot on June 14,” Sisler said, “so I hope you have a speedy recovery and come back and take the job away from me.”23

The Phillies continued to play inspired baseball for the rest of the year and finished in third place with 81 wins. After the season, Waitkus spent four months, beginning in November, in Clearwater Beach, Florida, working out under the guidance of Phillies’ trainer Frank Wiechec. There under the taskmaster Wiechec, Waitkus ran on the beach each day and went through demanding physical training to get back into baseball shape. Later Waitkus called his time in Florida “the four most horrible months of my life. Worse than anything in the Army — worse than New Guinea or anyplace in the Philippines.”24 But all of that hard work most certainly saved his baseball career.

While in Clearwater Beach, Waitkus also met Carol Webel, a pretty 20-year-old blonde from Albany, New York, who was vacationing with her family. Carol became an important part of Waitkus’s support system in his recovery from the shooting. He frequently observed that the shooting had almost cost him his life but it also caused him to find the future Mrs. Waitkus. After carrying on a long-distance relationship, they were married in November 1951 in Albany’s St. Patrick Roman Catholic Church. Teammate Bill Nicholson served as best man.25

A couple of years later Waitkus had an off-season radio show near their home in Albany called “The Sports Review.” The show consisted of his telling sports stories and highlighting the top athletes of the day. His broadcast on his second wedding anniversary, however, was a touching personal reminiscence, delivered in the third person, of how he had met Carol and how she had ultimately helped his recovery, mentally and physically. He described the grueling workouts in Clearwater and

Then, he met a girl. A girl who knew nothing of baseball. . . Their few “Hellos” on the beaches grew to infrequent dates. Slowly he started to withdraw from his shell and lose the fear he had developed of people. Slowly, through her influence, he started to take interest again in the world around him. And with her quiet confidence to help him, he went into his training with renewed interest. She had faith he could come back, so he HAD to do it, for her sake. When the going got rough, she was always there to cheer him up. When he felt like quitting, she was there to prod him on. . . . With her comforting presence in the background, he went on to a great season and a World Series.

That year the newspapers called his the Comeback of the Year, but he didn’t do it alone. The season ended and the companionship grew into something deeper. As it happens in fiction, they were married, and went back to baseball together. . . 26

Waitkus’s recovery, while long and arduous, was nothing short of miraculous. He was in the Whiz Kids’ Opening Day lineup in 1950, playing first base and batting third against the Brooklyn Dodgers. For the day in the Phillies’ 9-1 win, Eddie was 3-for-5 with a run batted in. He went on to start all 154 games at first as the Phillies nosed out the Dodgers for their first pennant in 35 years.

His Whiz Kids teammates respected and admired the veteran Waitkus in the clubhouse and off as well as on the field. Steve Ridzik, who was a 20-year-old rookie pitcher, remembered that in spring training Waitkus and Bill Nicholson would invite rookies to eat with them and always picked up the check. After dinner Waitkus and Nicholson would put the rookies in a cab back to the hotel while they went clubbing. Bubba Church, another rookie pitcher, recalled how Eddie’s calm demeanor when he would come to the mound in a tight spot always settled him down. Waitkus would say, “Hey, sweets, let’s slow that engine down just a bit. Let’s get it back together.”

Robin Roberts recalled how Waitkus was always upbeat in the clubhouse, although he wasn’t overly loud or talkative. His favorite sayings were “How goes the battle?” and “Keep the faith.” Rookie Paul Stuffel remembered Waitkus singing “My Heart Goes Where the Wild Goose Goes,” in the shower after a Phillies victory.27

Waitkus played a key role in the Phillies’ pennant-clinching victory over the Dodgers in Ebbets Field on the last day of the season, hitting a Texas League single in the top of the 10th, eventually scoring the winning run on Dick Sisler’s three-run homer, and then squeezing the final out, a popup from Tommy Brown, in the bottom of the 10th to clinch the pennant.28

For the season he went to the plate 702 times, scored 102 runs, and hit a solid .284. He even garnered some votes for Most Valuable Player, finishing 24th, and won the Associated Press’s Comeback Player of the Year Award in a landslide.

The long season and the World Series, however, wore Waitkus down physically and emotionally. It’s difficult to know if there was any carryover affect for the 1951 season, but it was a disappointment for both the Phillies, who slumped to fifth place with a sub-.500 record, and Waitkus, who hit only .257, his lowest full-season average by 27 points. With rumors flying that the Phillies wanted to trade him, Eddie rebounded in 1952 to hit .289 as the Phillies improved to fourth place, finishing 20 games over .500. On June 22 in Shibe Park, Waitkus had one of the best days of his career, going 6-for-9 in a doubleheader, including a perfect 4-for-4 in the second game.

On the final day of the 1951 season Waitkus was involved in a controversial play that is still talked about today. The Phillies were playing the Dodgers in Philadelphia in a game Brooklyn had to win to tie the resurgent New York Giants, who had trailed the Dodgers by 13 ½ games on August 26, for the pennant. The Dodgers fell behind 6-1 and then 8-5 before rallying to tie the score 8-8 in the ninth. In the bottom of the 12th the Phillies had the bases loaded with two outs when Waitkus smashed a low line drive up the middle that second baseman Jackie Robinson dove for and appeared to trap behind second base. The winning run scored as Robinson, momentarily stunned, rolled over on the ball. Except that umpire Lon Warneke signaled that Robinson had caught the ball, ending the inning. The protestations of the Phillies were to no avail and the game continued into the 14th inning when Robinson hit a home run off Robin Roberts to send the Dodgers into a three-game playoff against the Giants. But for that controversial call the Giants would have won the pennant outright and Bobby Thomson would not have had the chance to hit his “Shot Heard Round the World” a couple of days later.29

Waitkus rebounded from 1951 even though Ruth Steinhagen was declared sane and released from the mental hospital just after the 1952 season got under way.30 He confided in Russ Meyer that her release made him very uneasy because she had apparently told the Chicago police after her arrest in 1949 that she would kill him for sure if he ever got married.31

Phillies manager Steve O’Neill, who had replaced Eddie Sawyer in June of 1952, batted Waitkus eighth in the batting order after the All-Star break, in spite of his solid average.Then, in February of 1953 the Phillies acquired Earl Torgeson from the Boston Braves, another left-handed first baseman who had twice hit more than 20 home runs in a season. It was clear that the Phillies wanted more pop from first base, even at the expense of defense.32 As a result, Eddie played only 59 games at the position. He was also 7-for-20 as a pinch hitter and batted .291 for the season.

Waitkus became disgruntled riding the bench and began to drink more heavily. In late September with the Phillies battling for first place, he left the team without permission, ostensibly to visit his ailing father in Boston. His father, it turned out, was not seriously ill, although Waitkus apparently thought he was. Phillies owner Bob Carpenter was furious and suspended Waitkus without pay for the last week or so of the season. Waitkus later admitted making a mistake and admitted that the Phillies were fully justified in suspending him.33

The Phillies mailed Waitkus a contract for 1954 that included a substantial pay cut. Waitkus wrote “N.S.F.” on the contract, for “not sufficient funds,” and mailed it back. He also included a personal letter of apology to Carpenter for jumping the team. It apparently did not assuage Carpenter, who had announced that Waitkus would go to the highest bidder.

After rejecting a second contract offer, Waitkus finally signed for 1954 and reported to Clearwater. Manager O’Neill, however, did not play Waitkus in a single exhibition game that spring, much to Eddie’s disgruntlement. When he finally demanded to know why from Carpenter, he was told that he just been sold to the Baltimore Orioles.34

The 34-year-old Waitkus was sad to leave the Phillies but hopeful of being able to play every day again with the Orioles. His main competition at first base was power-hitting Dick Kryhoski. As luck would have it, Kryhoski broke his wrist when hit by a pitch in a spring-training game just after Waitkus was purchased. As a result, Waitkus started the season playing regularly. He got off to a poor start, however, and was hitting only .170 in early May, prompting manager Jimmy Dykes to insert Kryhoski into the lineup upon his return.

Although Kryhoski hit fairly well, after three weeks Dykes inserted Waitkus back at first base, with good results. By early June Waitkus was hitting .290 when he sprained an ankle in Boston while running the bases. He missed two weeks and for the rest of the season alternated with Kryhoski.35 For the year Waitkus batted .283 in 95 games and 349 plate appearances for the seventh-place Orioles. Most impressive, however, was his 1.000 fielding average: In 78 games at first base Eddie did not make a single error.

Although Waitkus rarely complained about it, he was increasingly bothered by lower-back spasms, apparently related to adhesions from the surgery to remove the bullet. He began the 1955 season on the disabled list and thereafter played sparingly, appearing in only 38 games by late July. The Orioles under new manager Paul Richards were headed into a youth movement and on July 25 gave Waitkus his unconditional release.

Five days later the Phillies signed Waitkus to spell struggling rookie Marv Blaylock at first base. Waitkus joined his old club in Cincinnati and smacked a pinch-hit single in his first game back. He went on to play in 33 games for the Phillies in the last two months of the season, batting .280.

On September 20 in Ebbets Field in Brooklyn, the 36-year-old Waitkus played his last major-league games as the Phillies lost a doubleheader to the Dodgers. In the fourth inning of the first game, Eddie smashed a home run over the billboards in right field off Don Newcombe to tie the score, 1-1. It was his second home run of the season and only the 24th of his career. Although it was out of character, Waitkus tipped his hat to his wife, Carol, in the stands after crossing home plate.36 In the third inning of the second game Waitkus lined a single to center field off Roger Craig for the last of the 1,214 base hits in his career. He finished with lifetime batting average of .285.

The Phillies released Waitkus in October and he decided to retire rather than try to hang on another year in the majors or play back in the Pacific Coast League. He obtained a job in marketing and sales with Eastern Freightways, a New Jersey-based trucking firm. He and his family, which now included daughter Ronni and son Ted, were soon relocated to Buffalo, New York. Without baseball, Waitkus’s drinking became more of a problem as did his depression, which he had battled since the shooting. Now he self-medicated his deepening depression with alcohol.

All of this took a toll on his family and in 1960 Carol took the kids and moved to Albany to be near her family. Eastern Freightways transferred him to Camden, New Jersey, and Waitkus continued his downward spiral. Finally, in late February 1961 he was admitted to the Veterans Hospital in Philadelphia with a nervous breakdown. He spent several days there, but apparently did not follow up on the prescribed counseling after his release.37

Waitkus did not return to the trucking company, but instead took a job in sales at Wanamaker’s Department Store in Philadelphia. One of baseball’s sharpest dressers was now selling men’s clothing. By the time of a Whiz Kids’ reunion in 1963 Waitkus had moved to Waltham, Massachusetts, to live with his sister Stella and work selling sporting goods at the Grover Cronin department store.

Shortly thereafter, Waitkus moved out of his sister’s home and rented a room on the second floor of a home on Fayette Street close to Harvard University in his hometown of Cambridge. There he lived alone for the rest of his life. Those years were very quiet ones. Waitkus shied away from much contact with baseball or his old schoolboy chums, although he did talk baseball with the neighborhood kids.

The one real positive of Waitkus’s later years began in 1967 when he started working during the summers as a baseball coach and counselor at the Ted Williams Baseball Camp in Lakeville, about 45 minutes south of Boston. Waitkus connected with the campers, many of whom didn’t even know that he was a former big leaguer. He acquired a great admirer in Ted Williams, who later said, “I always knew Eddie Waitkus was a great ballplayer, but he was a hell of a man, too. The kids at camp loved him. He was magnificent with them, and we were truly lucky to have him. He was a classy-looking hitter and a classy-looking fielder. I loved that camp, being around the kids, teaching baseball. And I know Eddie did too.”38

In June 1969 Waitkus took time out from his duties at camp to travel to Philadelphia, where he was honored at a Phillies game for the fans’ selection of him as the greatest first baseman in Phillies history. He beat out controversial slugger Dick Allen, who was still with the Phillies in 1969, for the honor. According to Eddie, “It was a popularity contest. In essence, it proved one thing — the love affair between the people of Philadelphia and the Whiz Kids does not die quickly.”39

In the fall of 1971, Waitkus fractured his hip when he fell while installing storm windows on the second story of the house where he rented a room. Although he had quit drinking, he continued to be a heavy smoker. According to his son Ted, who attended the Ted Williams camp with his dad in the summers, “His Benson and Hedges Menthol 100s never left his side.” Eddie walked with a pronounced limp and used a cane that summer at the baseball camp, but still taught kids how to hit.

He felt so poorly, however, that he left camp about a week early and drove back to Cambridge. Within days of returning home, he entered the VA Hospital in Jamaica Plain with pneumonia. He was soon diagnosed with esophageal cancer and would never leave the hospital. He died on September 16, 1972, and was just 53 years old.

Waitkus was a card-carrying member of what has become known as the Greatest Generation. But the horrors of his war experience and then his almost fatal shooting took a large toll on him. His drinking, depression, and anxiety issues would now be recognized as post-traumatic stress disorder and surely contributed to his early death. But he will always be remembered as a key member of the 1950 Whiz Kids and as one of the smoothest fielding first baseman of his or any time.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted:

Johnson, Lloyd, and Miles Wolff, eds., The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball (2nd ed.) (Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America, Inc. 1997).

Marshall, William, Baseball’s Pivotal Era: 1945-1951 (Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky, 1999).

Orodenker, Richard, ed., The Phillies Reader (Philadelphia: Temple Univ. Press, 1996).

Paxton, Harry T., The Whiz Kids the Story of the Fightin’ Phillies (New York: David McKay Company, Inc., 1950).

Spalding, John E., Pacific Coast League Stars, Vol. II — Ninety Who Made It In the Majors, 1903 to 1957 (Manhattan, Kansas: Ag Press, 1997).

Westcott, Rich, and Frank Bilovsky, The New Phillies Encyclopedia (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1993).

Clayton, Skip, “Eddie Waitkus — Slick Fielding First Baseman Came Back from Shooting Incident,” Phillies Report, undated copy.

Fay, William, “Lionized Cub — Eddie Waitkus Lives Up to the Chicago Tradition of Great First Sackers,” Sportfolio, July, 1947.

Fay, William, “They Woke Up the Busher,” Baseball Digest, May, 1947.

Rogers, C. Paul, III, Book Review, “An American Tragedy,” Elysian Fields Quarterly, Spring 2003.

Eddie Waitkus clippings file, National Baseball Library, Cooperstown, New York.

Notes

1 Charles C. Alexander, “Eddie Waitkus and Bernard Malamud: Life Versus Art,” Nine — A Journal of Baseball History and Social Policy Perspectives, Spring 1998: 15.

2 John Theodore, Baseball’s Natural: The Story of Eddie Waitkus (Carbondale, Illinois: Southern Illinois University Press, 2002), 22.

3 Theodore, 22.

4 Burns would go on to play in five more years in the minors, mostly with the Toronto Maple Leafs and San Francisco Seals.

5 Theodore, 23-24.

6 Ed Rumill, “The Only Cub Regular Who Hit .300 in 1946,” Baseball Magazine, March 1947, 330.

7 Theodore, 24-25.

8 Theodore, 25.

9 Richard E. Beverage, The Angels — Los Angeles in the Pacific Coast League 1919-1957 (Placentia, California: The Deacon Press, 1981), 135-137; Theodore, 28.

10 Theodore, 27.

11 Theodore, 29-30, 115-119.

12 Theodore, 116-118.

13 William Fay, “They Woke Up the Busher,” Baseball Digest, May 1947, 41; Richard Goldstein, Spartan Seasons — How Baseball Survived the Second World War (New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., 1980), 243.

14 Waitkus had encountered the Cardinals’ Fred Martin, whom he knew from his Texas League days and managed to get him assigned for rations and quarters to the 544th so that he could pitch for his unit. He won, 1-0. Goldstein, 244.

15 Theodore, 29.

16 Eddie Gold and Art Ahrens, The New Era Cubs: 1941-1985 (Chicago: Bonus Books, 1985), 47; Theodore, 31-33.

17 Rumill, 329.

18 Theodore, 36-37.

19 Robert L. Burnes, “Why the Waitkus Deal?,” Baseball Digest, March, 1949, 62.

20 Theodore, 38.

21 Theodore, 40.

22 The account of the Waitkus shooting is taken largely from Robin Roberts and C. Paul Rogers, III, The Whiz Kids and the 1950 Pennant (Philadelphia: Temple Univ. Press, 1996), 174-177; Robert A. Greenberg, “Swish Nicholson — A Biography of Wartime Baseball’s Leading Slugger (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., Inc., 2008), 194-196; Mark McGuire and Michael Sean Gromley, Moments in the Sun — Baseball’s Briefly Famous (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., Inc. 1999), 102-104; Ron Visco and Bruce Markusen, “Fatal Attraction: The Woman Who Shot Eddie Waitkus, Elysian Fields Quarterly, Fall 1999: 28-31; Alexander, 16-18; and Theodore, 2-5.

23 Theodore, 50-51.

24 “Ed Waitkus: Comeback of 1950,” Sport Life, August, 1950: 16; Alexander, 20.

25 Theodore, 54, 84-85, 88.

26 McGuire and Gormley, 106-107.

27 Roberts and Rogers, 169, 269. The name of the song is actually “Cry of the Wild Goose.”

28 Roberts and Rogers, 13-15.

29 Carl Lundquist, “Drama in Philadelphia,” Baseball Research Journal, 1997: 3-4. The Phillies believed that Robinson trapped the ball for the rest of their days. Robin Roberts saw Jackie Robinson at a banquet that winter and said to Robinson, “Jackie, you didn’t catch that ball.” Robinson replied, “What did the umpire say?” Robin Roberts and C. Paul Rogers III, My Life in Baseball (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2003), 104-105.

30 Steinhagen lived a very quiet, almost reclusive life in North Chicago, not far from Wrigley Field. She died on December 29, 2012, at 83, although her death went unreported in the press until March15, 2013. Bruce Weber, “Ruth Steinhagen is Dead at 83; Shot a Ballplayer,” New York Times, March 24, 2013: A22.

31 Theodore, 89-90.

32 Frank Yeutter, “They Can’t Bump Off Waitkus,” Baseball Digest, September 1953: 45-46.

33 Theodore, 101-103.

34 Theodore, 103-104.

35 Both Waitkus and Kryhoski were left-handed hitters and alternated as the regular first baseman the rest of the year.

36 Theodore, 109.

37 Theodore, 113-114.

38 Theodore, 124-125.

39 Theodore, 128.

Full Name

Edward Stephen Waitkus

Born

September 4, 1919 at Cambridge, MA (USA)

Died

September 16, 1972 at Jamaica Plain, MA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.