Fred Sanford

“Yes sir, it’s great to be a Yankee,” Fred Sanford said.1 Making it even greater, he was traded from the nearly bankrupt St. Louis Browns to the pinstriped promised land.

“Yes sir, it’s great to be a Yankee,” Fred Sanford said.1 Making it even greater, he was traded from the nearly bankrupt St. Louis Browns to the pinstriped promised land.

Presented with the opportunity of a lifetime, Sanford flopped.

After the right-hander had lost 21 games for the Browns in 1948, the Yankees paid $100,000 plus three players to acquire him. The consensus opinion was that he could win 15 or 20 in New York and return the club to its rightful place on top of the standings. It didn’t happen; the deal made Sanford the Yankees’ “$100,000 lemon” and ruined his career.

John Frederick Sanford was born on August 9, 1919, in Garfield, Utah, a mining town of a few dozen homes built by the Utah Copper Company just outside Salt Lake City. It is now a ghost town, but during Sanford’s childhood the fathers worked in the mine or the smelter while the children splashed in the swimming hole known as Bare-Bum Beach and, if they dared, climbed Hundred Foot Cliff. Fred was one of three sons and four daughters of Frederick Charles Sanford and the former Mary Alice Unsworth, immigrants from England.

Sanford pitched for a Junior American Legion team that won back-to-back state championships, and in semipro ball around Salt Lake City. He earned a tryout with the Pacific Coast League San Diego Padres in 1938, but the club kept him around for six weeks with only one appearance before handing him his release. The next year a Yankees scout told him he didn’t throw hard enough to make it in pro ball. After Sanford defeated the bearded House of David barnstorming team, Browns scout Jacques Fournier signed him to a $110-a-month contract with the Browns’ Class-C affiliate in Youngstown, Ohio.

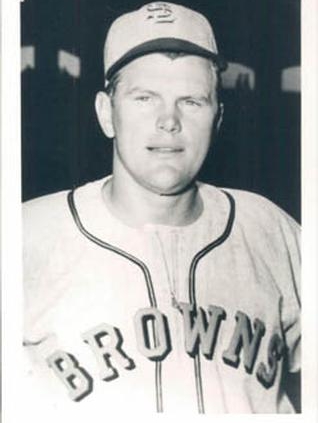

At 6-feet-1 and around 200 pounds, blond and blue-eyed, “Sandy” looked the part of a pitcher. He rose through the farm system in fits and starts. With the top farm club in Toledo in 1942, he recorded complete-game victories in exhibitions against the Yankees and Tigers. The next year he finished 13-9 and earned a September call-up. In three relief appearances for the Browns, he gave up just two runs in 9⅓ innings.

Sanford had married his high-school girlfriend, Bonnie Elaine Brown, in 1941, and she was pregnant with the first of six children. Impending fatherhood didn’t keep him from being drafted after the 1943 season. “I was in an outfit where you had to dig in the mud and do real soldiering,” he recalled.2 He served more than two years in the Army field artillery with the 41st Infantry Division, surviving combat in New Guinea and the Philippines, and winding up with the occupation troops in Japan after the war ended.

Returning home in time for spring training in 1946, Sanford learned that the Browns prohibited families from joining the players in Anaheim, California. He rebelled, telling a reporter, “I didn’t see my wife and kids for two years while I was serving in the Pacific theater, and I intend to see something of them now.”3 Sent back to Toledo for his third year at the highest minor-league level, he led the American Association with a league-record 154 strikeouts, posting a 2.74 ERA with a 15-10 record.

Called up in September, Sanford arrived with a bang. In his first start he shut out the Yankees on five singles. A week later he blanked the White Sox on four hits without allowing a runner to reach third base. His season ended sourly when he was torched for seven runs in four-plus innings in his final start, but he looked like a welcome ray of hope for the seventh-place Browns.

This Fred Sanford was no junk dealer. He featured a pitcher’s meat and potatoes: fastball, curve, changeup. He opened the 1947 season in the bullpen, but moved into the rotation in June. He beat the Yankees, 4-3, in his first start, then beat them again a week later by the same score.

On July 27 Ted Williams broke up a tie game with a booming two-run homer off Sanford in the sixth. Two batters later Boston’s Jake Jones topped a dribbler up the third-base line. As it rolled foul, Sanford threw his glove at the spinning ball. By rule, Jones was awarded a triple that traveled all of 60 feet. The Browns protested that the ball was dead because it was foul, but umpire Cal Hubbard said the rule made no such exception. Sanford acknowledged that he had suffered a brain cramp because he was still seething over the Williams home run. As the Browns lost 95 games and finished last, Sanford compiled a creditable 3.71 ERA, but a 7-16 record.

He was the Opening Day starter in 1948. Facing the Cleveland Indians, he walked the leadoff batter and gave up two hits in the first inning, but escaped with only one run scoring. When the first two batters singled in the second, manager Zack Taylor relieved him. “It’s not his arm that gets him into trouble, it’s his head,” Taylor said. “If he opens the game with anything other than perfect control he seems to worry about getting the ball over the plate and he’s just an ordinary pitcher.”4

One sportswriter called Sanford “the barrel-chested, strong-armed ace of the Brownie staff.”5 The team again was going nowhere, heading for 94 defeats and a sixth-place finish. Sanford lost his 19th game on September 15. With more than two weeks left in the season, the club made no effort to protect him from a 20th loss. He took his regular turn, splitting four more decisions to finish 12-21, leading the league in losses. Taylor said, “I probably could have saved him five or six games with good relief pitchers.”6 Good hitting would have helped, too; the Browns scored no more than two runs in 12 of Sanford’s defeats.

With all that, Sanford was a below-average pitcher in 1948. He recorded a 4.64 ERA and gave up 19 home runs, third most in the league. AL batters hit .279 against him, he walked more than he struck out, and he completed only nine of 33 starts.

The Browns, as usual, were practically broke. A year earlier they had tapped the Red Sox for a reported $375,000, dealing away slugging shortstop Vern Stephens and pitchers Jack Kramer and Ellis Kinder. Now they turned to the AL’s other big bankroll, the Yankees.

New York general manager George Weiss said the Browns offered him a choice among three pitchers. He consulted several of his leading players, including Joe DiMaggio and Tommy Henrich , and picked Sanford. St. Louis threw in catcher Roy Partee in return for the Yankees’ third-string catcher, 23-year-old Sherman Lollar, pitchers Red Embree and Dick Starr, and – most important – $100,000.

The Yankees were betting big that Sanford was the arm they needed to bounce back from a third-place finish. The new manager, Casey Stengel, said he went to sleep that night dreaming of a pennant. The next morning he learned that the defending champion Indians had acquired pitcher Early Wynn and former batting champ Mickey Vernon from Washington. “The Yankees went to bed pennant winners and woke up in second place,” Stengel said.7

Sanford was working in the Salt Lake City police garage when he got news of the trade. He said he wasn’t surprised, because several Yankees had told him he would be joining them next year. His first move: go on a diet. He had ballooned to more than 225 pounds, and wanted to drop below 200. Arriving in spring training hungry, the $100,000 man told a reporter, “I can pitch well enough to justify the deal. That is, I can pitch successfully for the kind of club I’m with now.”8

The Yankees opened the 1949 season without DiMaggio, who had surgery to remove a bone spur from his heel. Even so, the team won its first four games. In his first start, on April 23 at Boston, Sanford fell behind, 2-0, but the Yankees exploded in the fourth to give him a 6-2 lead. He gave it right back. Sanford surrendered a double, walked two, and shortstop Phil Rizzuto threw away a groundball. Then Boston’s Vern Stephens hammered a grand slam to put the Red Sox up, 7-6.

Stengel pulled Sanford from the game and didn’t give him another start for more than a month. The manager, in his first year, was trying to live down his reputation as a loser and a clown, and was under pressure to lead the Yankees back to the World Series. With another team, with a more secure manager, Sanford might not have been on such a short leash. But with the Yankees under Stengel, it was win now or else.

Sanford never regained his manager’s confidence. Most of his 11 starts came against tail-end teams or in doubleheaders when the club needed an extra arm, and most of his relief appearances were in mop-up roles, when the Yankees had fallen behind. He pitched fairly well, with a 3.87 ERA, but in only 95⅓ innings. Even after winning three September starts to bring his record to 7-3, he was a spectator at the World Series as New York defeated Brooklyn in five games.

“I tried too hard,” he said. “I pressed every time I worked until August.”9 Stengel voiced a charitable view: “Maybe he is one of those fellows who can’t adjust overnight when traded from a second division [team] to a pennant contender. I know he was a disappointment during the first half of the season, but he improved considerably later, and if you look up the records you’ll see he did well in September.”10

Stengel gave him 10 starts in the first half of 1950, mostly against the league’s weak sisters. Sanford completed only two, with a 5.10 ERA, and went back to the bullpen. He left the team around September 1 when his father got sick and died. After he returned, he pitched just once as the Yankees charged from behind to claim another pennant. Again, he sat out the Series.

With a 4.55 ERA and 5-4 record, Sanford was “the forgotten man of the Yankee pitching staff,” according to the New York Times’s James P. Dawson.11 His name cropped up in offseason trade rumors, but no deal materialized. The next spring he vented his frustration: “I cannot do myself or the Yankees any good pitching 113 innings. I want to pitch 250. I cannot maintain condition sitting around. Nor am I gaited for sitting and thinking. That’s no good if, nearing 32, you haven’t made a place for yourself.”12

“I would be delighted to pitch him as often as he said he should pitch,” Stengel said. “But if Fred gives me a couple of poor outings, what am I to do?”13 Sanford pitched just 11 times for New York in 1951 before he was not only forgotten, but gone.

At the June 15 trading deadline, the Yankees shipped Sanford to Washington with veteran reliever Tom Ferrick and Triple-A pitcher Bob Porterfield for lefty Bob Kuzava. The Washington Post greeted the newcomers with a sarcastic headline: “Nats Pick Up Three Losers From Yankees.”14

“I was convinced Sanford could help us, and all our good hitters agreed,” Yankee GM Weiss said later. “He was just a flop with us, that’s all.”15 Emblematic of what Stengel thought of him, he started only three games against New York’s main challengers, Boston and Cleveland. Sanford’s 4.18 ERA and 12-10 record in two-plus seasons stamped him in Yankees history as the “$100,000 lemon.”

Sanford and Ferrick were throw-ins in the trade. Porterfield was the man Washington manager Bucky Harris wanted; the right-hander had pitched for him when Harris was managing New York. Porterfield became the Senators’ ace for the next four years.

In Sanford’s first start for Washington, he held the Indians to one run in 7⅓ innings and won a spot in the rotation. But after seven starts his ERA stood at 6.57. The Senators shuffled him back to the Browns in a waiver deal. He fell apart in his return to St. Louis, walking 23 batters in 27⅓ innings with a 10.21 ERA. That was below even the Browns’ standards, and they traded him to Portland of the Pacific Coast League after the 1951 season. His big-league career was over at 32.

Sanford pitched for two years in Portland before a sore shoulder forced him to retire in the spring of 1954. Returning home to Salt Lake City, he picked up his offseason job as a deputy sheriff and criminal investigator. He later worked as a production-control specialist for the Hercules Powder Company, a manufacturer of explosives for the military.

Fred and Bonnie were married for 70 years and raised five children; another died in infancy. Fred Sanford died at 91 on March 15, 2011. Bonnie died less than two months later.

This biography is included in “20-Game Losers” (SABR, 2017), edited by Bill Nowlin and Emmet R. Nowlin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted:

Familysearch.org.

“Sanford, J. Fred.” Obituary in the Salt Lake Tribune, March 27, 2011. genealogybank.com/doc/obituaries/obit/13644C78AC6A6068-13644C78AC6A6068, accessed July 17, 2016.

Sanford, John Frederick. Player questionnaire (1964) in his file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame library, Cooperstown, New York.

Wadley, Carma. “Memories of a Company Town.” Deseret News (Salt Lake City), August 12, 2005. deseretnews.com/article/600155105/Memories-of-a-company-town.html?pg=all, accessed July 17, 2016.

Notes

1 Dan Daniel, “Sanford Goes Hungry to Feast on Wins,” The Sporting News, March 16, 1949: 3.

2 Frederick G. Lieb, “Big Fred’s Blanks Make Brownie Fans Blink,” The Sporting News, October 2, 1946: 9.

3 “Ex-GI Sanford Balks at Browns’ Ban on Families,” The Sporting News, February 14, 1946: 6.

4 Dent McSkimming, “Sanford, Prospective Gibraltar of Browns’ Mound Staff, to Get Plenty of Work, Taylor Says,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 3, 1948: 4B.

5 Ray Nelson, “A’s Beat Browns for Ninth in Row and Regain First Place,” St. Louis Star-Times, May 12, 1948: 22.

6 W.J. McGoogan, “Browns Swing 5-Player Deal With Yankees, Drop Out of Trade Mart,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, December 14, 1948: 2B.

7 Shirley Povich, “This Morning,” Washington Post, December 15, 1948: 17.

8 Daniel, “Sanford Goes Hungry.”

9 Daniel, “Sanford Thinks Sanford Fills Casey’s Bill,” New York World-Telegram, March 6, 1950, in Sanford’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame library, Cooperstown, New York.

10 “Sanford Becomes 15th Yank to Sign,” New York Times, February 1, 1950: 35.

11 James P. Dawson, “Sanford Seeking Role as Starter,” New York Times, February 26, 1951: 34.

12 Daniel, “Sanford ‘Mystery’ Solved by Fred – ‘I Can Win if They Let Me Pitch,” The Sporting News, March 7, 1951: 4. As usual, Daniel “cleaned up” the quotes.

13 Ibid.

14 “Nats Pick Up Three Losers From Yankees,” Washington Post, June 16, 1951: 13.

15 “Weiss Would Like to Forget ’48 Deal for Fred Sanford,” The Sporting News, February 8, 1956: 13.

Full Name

John Frederick Sanford

Born

August 9, 1919 at Garfield, UT (USA)

Died

March 15, 2011 at Salt Lake City, UT (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.