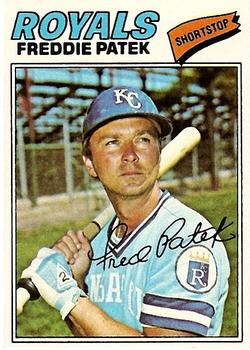

Freddie Patek

“How does it feel to be the smallest player in the majors,” a Houston reporter asked Fred Patek in 1968. “A heck of a lot better than being the tallest player in the minors,” countered the rookie shortstop.1

“How does it feel to be the smallest player in the majors,” a Houston reporter asked Fred Patek in 1968. “A heck of a lot better than being the tallest player in the minors,” countered the rookie shortstop.1

Patek’s quip matched his quickness on the field and the basepaths for 14 years in the major leagues. At 5-feet and change tall, he stood as the smallest player of his time. Patek often claimed that he was 5-foot-5, but throughout his career most sources listed him at 5-foot-4. The origin of his lost inch began with Bob Prince, the Pittsburgh Pirates radio announcer. Prince measured Patek on TV shortly after he debuted in 1968. “I came out 5-4,” chuckled Patek, “but I think Bob wanted me to come out 5-4.”2 Others stretched the truth the other way. When Patek joined the California Angels as a free agent in 1980, their PR director asked, “How tall are you?” “I’m around 5-6,” Fred said. “How come you were listed at 5-4?” “I guess 5-6 sounded better.” “Well” said the director, “from now on you’re 5-6.”3

Whatever his height, Patek beat back several challenges. He played only one year in high school and caught the attention of scouts while playing ball in the Air Force. He was drafted in the 22nd round of the 1965 amateur draft, yet he posted a career WAR second to only one first-round draftee that year.4 And he battled an all-star shortstop for playing time as a Pirate, yet became a three-time All Star for the Kansas City Royals.

Frederick Joseph Patek was born on October 9, 1944, in Oklahoma City. His family soon moved to Seguin, Texas, where he grew up. “Three or four weeks later my dad left to go overseas, and my mom went back home.”5 Her sister’s brother — Freddie’s uncle Joe Faldik — lived in Yoakum, Texas, so she stayed with him until her husband came back.

Freddy preceded two brothers and two sisters. Kenny, born next, nearly tried out for the Pittsburgh Pirates. Instead, he chose to serve his country in Vietnam. He earned two Purple Hearts after twice enduring serious wounds to his chest and legs.6 Cathy, Anthony, and Annette filled out the rest of the family parented by Joe and his wife, Annie (Faldik). Joe Patek ran a butcher shop that kept his wife and children busy. As youngsters Fred and his siblings made hamburger meat in the mornings. In the afternoons they stuffed sausage to sell the next day at the Seguin meat market.7 At age 7, Fred helped on his uncle Joe’s bread truck. At 4:00 A.M. each morning he woke up at 965 E. Weinert St. to stack bread trays for 12 hours at $2.00 a day. His early work ethic matched his hard-nosed play as a kid. Uncle Joe would drive the 7-year-old to nearby Yoakum, to be regularly picked first among the older kids in sandlot games. “I was better than all of them,” Fred crowed.8 He excelled for six years in Little League for the Lions Club and two years in American Legion in preparation for high school.

Patek played third base his junior year at Seguin High School. Earning all-district and all-state honors, he was poised to lead the Matadors his senior year.9 However, the school made a coaching change and the new coach refused to allow Fred to try out.10

After graduation in 1963, Patek received a few scholarships, but went to Houston to work instead. On July 13 he played in the South Texas All-Star game in San Antonio. At that game, former third baseman Pinky Whitney scouted and selected Patek to play in the annual Hearst Sandlot Classic.11 This tournament pitted invited players across the country to play a team of all-stars from New York. St. John’s University freshman baseball coach Lou Carnesecca watched Patek blast several home runs in practice. Carnesecca, who later coached the school’s great basketball teams of the 1980s, offered Patek a scholarship.12 “I wasn’t going to go to New York,” Fred said with a chuckle. Instead, “My mom called me, she said, ‘You need to come home. … You got your draft induction notice.’”13

On January 1, 1964, Patek joined the Air Force in San Antonio, Texas.14 At Grater Field on Randolph Air Force Base, he played a 140-game schedule for two years. “It was the best thing that could have happened to me because the scouts got a chance to see that I could play,” Fred said. “Had I gone on to college out of high school and played 30, 40, or 50 games a year, I probably would have never made it.”15 His play captured the eyes of two major-league scouts, Bob Zuk and Larry DeHaven of the Pittsburgh Pirates.16 On June 8, 1965, the Pirates drafted Patek in the 22nd round of the major leagues’ first amateur draft. Of all the first-round draftees that year, only Rick Monday, the first-ever pick, would score a better career WAR (33.1) than Patek’s 24.1.

After the draft, Patek’s father fell ill and the Air Force gave him a hardship discharge. The Pirates allowed Fred to tend to family business the rest of the year. The next spring he began his professional career, with Gastonia (North Carolina) of the Class-A Western Carolinas League. His hitting (.310/.401/.401) and 38 stolen bases placed him in the league’s all-star game, where he was named the MVP.17 The next day the Pirates promoted him to the Triple-A Columbus Jets of the International League. On August 10 the Pirates sent him to Double A to finish the year with Asheville (North Carolina) of the Southern League. Patek played all of 1967 at Columbus. His play at shortstop and center field along with leading the league with 42 stolen bases earned him another nickname, the Flying Flea.18

Patek began 1968 in Columbus and continued to burn on the bases, stealing 18 bags at a 90 percent clip. The Pirates called him up for his major-league debut on June 3. In Los Angeles, Dodgers lefty Claude Osteen collared Patek in four at-bats and he remained hitless in his first 12 plate appearances. On June 14 at Forbes Field, he got his first hit. He dropped a bunt single off Houston left-hander Denny Lemaster and got his first stolen base.19 The next day Patek slammed his first home run. Houston right-hander Don Wilson yielded the drive, which produced his first three RBIs.20 Soon after, Patek earned a nickname that stayed with him the rest of his career. Pirates announcer Bob Prince began calling him the Cricket during broadcasts. Patek chuckled, “[T]hey’d punch a bunch of … I guess they were selling crickets (metal noisemakers) all over Pittsburgh. So, at the ballpark you’d hear all the cricket sounds when I came to bat.”21

Just as Patek settled in, a fastball on June 18 stalled his season. “I got hit on the wrist by a Don Drysdale pitch and I played a month without knowing I had a cracked bone in my wrist. I knew something was wrong, but the first X-rays were negative and I kept playing.”22 He played a week with a heavily taped left wrist when new X-rays revealed the broken bone. He lost 33 games to the disabled list. The injury also affected Patek’s bat; he ended the season with five hits in his last 45 at-bats (.114).23

Soon after the season, Fred married Geraldine “Jerri” Freeze on October 12. They lived in Sarasota that winter while he played in the Florida Instructional League in preparation for spring training.24

Despite his injury, playing time looked brighter for Patek in 1969. Pirates manager Larry Shepard reluctantly inserted him full time at shortstop over incumbent Gene Alley. Alley, a two-time All-Star, suffered a sore right shoulder that forced him into a utility role. Patek played hot and cold all year, never feeling the confidence of Shepard, who doubted him.25 “I was a seven-inning ballplayer in 1969,” Patek complained. “I’d bat two, maybe three times a game and I was out of there for a pinch-hitter. They took away my aggressiveness. … So I batted eighth and you don’t get many chances to steal when you’re the eighth man in the order.”26 Patek finished with an anemic slash line of .239/.318/.296 with only 15 extra-base hits and 15 steals. He struck out a career-high 86 times. The Pirates saw his lackluster play as reason to platoon him in the coming season.

In 1970 the Pirates replaced Shepard as manager with the return of Danny Murtaugh. The Bucs moved from aging Forbes Field to Three Rivers Stadium on July 16. A new Tartan Turf surface required quickness and a strong arm from the shortstop position; Patek had both. But his 30 errors the year before led Murtaugh to lean on the veteran Alley. Patek played only 65 games and pinch-hit more times (13) than in the rest of his career combined (11). The Pirates won the NL East, but in the NLCS the Cincinnati Reds swept them in three games. Patek went hitless in the only game he played. As the year ended, Patek expressed his unhappiness with Pittsburgh. “They treat me like a kid,” he fumed. “They don’t say things in words. It’s in actions. They indicate they don’t think I can play every day. Baseball is no longer fun to me.”27

Early in his career, baseball was fun for Patek. He attracted much attention by other clubs. In 1968, the Mets offered left-hander Jerry Koosman for him; the Bucs turned them down.28 Dodgers manager Walt Alston believed Patek to be the National League’s most underrated player.29 Preston Gomez, skipper for San Diego, said, “If the Pirates ever want to trade him, I hope they speak to us.”30 Gomez nearly got his man late in the ’70 season as he and the Bucs flirted with an exchange of Patek for pitcher Pat Dobson.31 The deal fell through. Patek and the Bucs had to wait until December to find a trading partner.

On December 2, 1970, the Pirates traded Patek at the Winter Meetings. He found out from his manager, Roberto Clemente, while playing winter ball in Puerto Rico.32 They packaged him in a six-player trade with the Kansas City Royals. Pittsburgh acquired right-hander Bob Johnson along with shortstop Jackie Hernandez and backup catcher Jim Campanis. The Royals obtained spot starter Bruce Dal Canton, catcher Jerry May, and Patek. Surprisingly, the Pirates offered the Royals a choice between Patek and Alley, hoping they would take the older, injury-prone vet.33 The Royals wisely picked Patek, who was pleased he could now bat leadoff and steal more bases. “I want to go someplace where I can utilize my speed,” he said. “I did a lot of running in the minors. When I came to Pittsburgh from Columbus … I was aggressive. Everybody said I gave the club a big lift.”34 He soon gave a lift to the Royals with a career year in 1971.

The trade rejuvenated Patek. Batting leadoff, he stole 49 bases, beginning a string of eight consecutive years of 30 or more steals. He posted career highs in batting average (.267), at-bats (591), runs (86), hits (158), home runs (6), and triples (11, which led the American League). On April 30, he beat Baltimore with the first of six career walk-off hits. On July 9 at Minnesota, Patek became the first Royal to hit for the cycle. In the field he teamed with second baseman Cookie Rojas to form a remarkable double-play combo that included a four-year streak in which Patek led AL shortstops in double plays. As of 2018 only three shortstops have matched the record, George McBride, Roy McMillian, and Rafael Ramirez. Patek’s 301 putouts also led the league. For much of the season writers considered him an MVP candidate. However, he started pressing at the plate, hitting only .157 with three steals in September. He still finished sixth in the MVP voting, garnering 77 points. His play helped to elevate the Royals to second place in the AL West.

In November Patek went through a life-changing experience. At home one night he thought, “If I die right now on the spot, where would I go? The only answer I had was, ‘Straight to hell! … It was like God was saying, ‘This is your last chance, if you want eternal happiness in heaven, it’s up to you to go get it.’”35 Patek thought about quitting baseball after his spiritual epiphany but decided baseball was his way to do God’s work. He has embraced his Christianity ever since, but his faith would be tested over 20 years later by a family tragedy.

Patek dropped in nearly every offensive category in 1972, but he did deliver two walk-off hits in less than a week. On August 5 his single beat California, 2-1. Three days later his game-winning hit handed a 4-3 loss to Oakland’s future Hall of Famer Rollie Fingers. Patek’s modest offense did not affect his glove. He led the AL in Defensive WAR with a 3.2 mark, bolstered by a league-leading 510 assists, 18 Total Zone Runs, and 113 double plays, that again led all shortstops. Despite producing his weakest career slash line (.212/.280/.276), Patek’s stellar defense and 33 steals secured his selection to his first All-Star Game. The Royals fell back to fourth place, but they looked forward to a new home in 1973.

The Royals acquired Patek knowing they’d soon switch from grass to artificial turf. They did so in 1973, moving from Kansas City’s old Municipal Stadium to Royals Stadium (renamed Kauffman Stadium in 1993.)36 On April 10 Patek christened the new park with its first walk, stolen base, and run scored. On the new turf, Patek excelled defensively. “When I left Three Rivers, we were playing on it, but it was really hard, really fast, and I thought, ‘This is tough,’ Fred recalled. “The balls were just like lightning, so I changed my game. I moved deeper and I moved more parallel to the third baseman and it increased my range a lot.”37 At bat, Patek improved his slash lines slightly from ’72 while chipping in 36 steals and a 10th-inning hit to beat the Yankees on August 22. The Royals rebounded to second place in the AL West.

In up-and-down fashion, the Royals fell to fifth place in their division in 1974, their poorest showing since they began in 1969. Patek delivered another mediocre year with the bat, but did draw a career-high 77 walks along with his best hitting streak, 12 games. Again he paced the AL in double plays with 108. But team chemistry suffered between the players and manager Jack McKeon. Tension and conflicts foreshadowed a change to challenge the Oakland A’s dominance of the AL West.

McKeon battled his players and the media early in 1975. By July 23, the team replaced him with Whitey Herzog.38 The Royals reclaimed second place, but Patek continued to struggle at the plate. An ankle injury on July 10 sidelined him for 17 days. He returned to deliver a 10th-inning hit to beat Minnesota, 6-5, on August 4. Three days later he stung the Twins again, hitting his sixth and final leadoff home run, an inside-the-park round-tripper to start a 10-2 romp.39 On the bases he extended his streak of 30-plus steals with 32 thefts. The Royals finished as bridesmaids again to the Athletics, who won their fifth straight division crown. Oakland’s streak spanned all five of Patek’s years as a Royal. Kansas City pushed them often, finishing second three times. But under Herzog’s guidance, the Royals were on the verge of controlling the AL West for the next three years.

By mid-May of 1976 the Royals claimed first place in the division for the rest of the year. The team jelled with the emergence of future Hall of Famer George Brett, stars Amos Otis and Hal McRae, and pitchers Dennis Leonard and Paul Splittorff. They also ran wild on the bases. Patek stole over 50 bases for the first time (he had 51) and six other players stole 20 or more bases for a franchise record (218). The increased thefts were part of an early version of Whiteyball, a strategy Herzog perfected later with St. Louis. He built the roster to fit Royals Stadium with its artificial turf and challenging fences. Speed, defense, and line drives played better on the Royals’ carpet than fly balls that wilted in its huge power alleys. Herzog saw Patek as vital to his strategy. Artificial turf demanded deeper positioning, greater range, and a cannon arm from a shortstop. Herzog saw Patek as the prototype to play the position in the ’70s. “Patek, Bud Harrelson, and Larry Bowa are the three best I’ve seen at playing shortstop on the carpet,” Whitey exclaimed, “…but no one can play it any better than Fred.”40 Herzog’s praise endured even after managing Ozzie Smith in St. Louis during the 1980s. Patek’s play also earned him his second All-Star Game appearance.

Whiteyball propelled the Royals to win their first AL West crown in 1976. The night the Royals clinched the division, Patek and Rojas, in full uniforms, famously jumped into the right-field fountains to celebrate. “We jumped in there with our cleats and everything on,” Patek recalled. “If (Royals PR director Dean Vogelaar) hadn’t had the electricity in the fountains turned off, we could’ve been swimming out there like a couple of dead goldfish.”41

Patek hit well in the ALCS. He drove in four runs on seven hits with two doubles to bat .389; it was not enough. In the final game, Yankees first baseman Chris Chambliss led off the bottom of the ninth inning with a pennant-winning homer. Despite the loss, the Royals were poised to control their division and return to the postseason.

Before the 1977 season, Patek sought a five-year contract with the Royals. The team eventually signed him to a three-year deal worth $500,000.42 The 32-year-old shortstop then helped the club to a franchise-record 102 wins. They blended their usual speed and pitching with unusual power by slugging 146 home runs, more than double the 65 hit the year before. Patek produced his second-best season as a Royal. He generated career highs in doubles (26), RBIs (60), and steals (a league-leading 53). His steal of home on June 19 produced the 2-1 margin over Minnesota.43 On June 22 Patek got his “biggest thrill in baseball” when he belted his 1,000th career hit in a 4-3 win over Seattle.44 He recalled the fans’ standing ovation — “[T]hat was the first time I ever felt that people were applauding me for what I had accomplished instead for just being a little guy.”45 He played a career-best 154 games. A postseason rematch with the Yankees was next.

In the five-game ALCS, Patek repeated his .389 batting average, adding more power. He produced three doubles, a triple, and five RBIs. In the final game a brawl broke out between Brett and Yankees third baseman Graig Nettles. Both scuffled after Brett slid hard into Nettles on a first-inning triple. As the fight swelled, Patek felt someone pull him away from the scrum. Billy Martin dragged him to the pitcher’s mound and put an arm around him as the two watched the melee together. Billy’s protection of Fred mirrored a similar time when Martin managed in Texas. When a fight broke out then, “the next thing I knew, someone grabbed me by the back of my jersey. I thought. ‘Oh, man, this isn’t going to be good!’ I turned around and it was Billy Martin. … I knew he was going to lay me out. But no, instead he pulled me by the collar to the pitcher’s mound and said, ‘You just stay here with me. We’ll be out of trouble up here.’”46

Surprisingly, no one was ejected after the fight. “(Umpire Marty) Springstead told me he wasn’t going to throw Brett out,” Martin recalled. “This is a championship game and not the time to be throwing players out. If this game had been played in July, Brett would have been gone.”47

The game edged to the top of the ninth with the Royals leading 3-2. Three pitchers later the Yankees led 5-3 going into the bottom of the ninth. Frank White got a one-out single to bring Patek’s hot bat to the plate. His slash line positioned him to win the MVP of the series (.389/.400/.667). But on his 33rd birthday he hit Sparky Lyle’s slider sharply to Nettles who started a pennant-winning double play. As the Yankees celebrated, Tony Triolo from Sports Illustrated snapped the poignant photo of Patek sitting in the dugout alone, head in hands, in disbelief. “I just can’t believe we lost,” he sighed.48

The Royals rebounded to claim their third straight AL West crown in 1978. In the first half Patek played well, hitting .274 with 23 steals to earn his third trip to the All-Star Game. He batted for the first time in the midsummer classic, singling in three at-bats. He finished with 38 steals, the last time he would swipe over 30 bases. But his second-half struggles at the plate (.216/.284/.281) led to his final season as a full-time shortstop. In the playoffs the Royals tried to claim the pennant for the third consecutive year against the Yankees; it was not to be.

In the two prior ALCS meetings, the Royals lost in five games. In 1978 the Yankees ended the series in four games. After hitting .389 in both of the previous two playoffs, Patek cratered at the plate. His two-run homer helped rout the Yankees, 10-4, in Game Two, but it was his only hit in 13 at-bats. By next spring the Royals had plans for a change at shortstop.

In 1979 Patek started fewer than 100 games for the first time as a Royal. The 34-year-old lost a third of his playing time to youngsters U L Washington and Todd Cruz. Injuries plagued him. He played most of May with a hyperextended shoulder. On August 22 he suffered a sprained right ankle, putting him on the disabled list. He returned on September 14, only to play two innings on defense, his final appearance that year. After the season he was asked why he lost his job at short. Patek responded, “It was given away. I never had a job last year. …When I lost my job, I was playing well. … I was shuffled in and out of the lineup.”49 His Royals career was over at that point. The club finished second behind the California Angels, Patek’s new team for 1980.

Unhappy in a utility role, Patek tested free agency for the first time.50 On December 5, 1979, he signed a three-year deal for $550,000 with the Angels.51 He started strong at the plate. By mid-June, his OPS surged over .800, including two four-hit games, the first of which shocked the league. On June 20 he led off the game against the Red Sox with a double off the top of Fenway Park’s left-field wall; it was his shortest hit that day. By the end of the 20-2 blowout, Patek had joined Ernie Banks as the only two shortstops at the time to slug three home runs in a game. “You know, the thing I remember most from that game,” Patek recalled, “is that the fans in Boston gave me a standing ovation after the third home run. They did it so long that I went back out and tipped my hat. That’s really unique for a visitor, but Fenway and the Boston fans were special.”52 His outburst also produced a career-high seven RBIs. Days later, Patek talked about his playing bonus to manager Jim Fregosi, who reminded GM Buzzy Bavasi. “I had a contract, if I played 100 games,” Fred recalled. “It was a $25,000 or $50,000 bonus and when I got close to 100 games, they sat me on the bench.”53 He realized that Bavasi had ordered his playing time to rookie Dickie Thon to save the bonus money. The Angels packed it in and fell to sixth place.

In 1981 the Angels acquired Rick Burleson in a trade with the Red Sox to play shortstop. Before the players strike on June 12, Patek played sparingly, mainly at second base. After the season resumed on August 10, he played in only 10 games, batting just six times. With Burleson set at short, the Angels released Patek, the following April.54

Soon after Patek’s release, Burleson injured his right rotator cuff and his season was ended. Bavasi scrambled for a fix by contacting Patek to come back, but was immediately turned down.55 Patek remembered the bonus snub Buzzy pulled in 1980. “Bavasi was not a very good person. He was kind of nasty about stuff. … I did not care for that man at all,” he recalled.56 Instead, Dick Enberg hired Patek as a part-time color analyst for NBC’s backup Game of the Week. He analyzed six Saturday games in 1982 and three more in 1983. In 1984 he worked with Don Drysdale and Ken Harrelson on television for Chicago White Sox road games. In his last stint as an analyst, he paired with Phil Stone on KTVT for the Texas Rangers in 1985.57

In the late 1980s, Patek owned six Grandy’s homestyle-cooking restaurants in the Kansas City area. All of them went under by the early ’90s.58 In 1992 he worked as a roving minor-league coach for the Milwaukee Brewers. Soon after returning from a road trip that year, tragedy struck the Patek clan on July 21. A car crash left their 20-year-old daughter, Kimberlie, a quadriplegic.59 For three years she battled her spinal-cord injury on a respirator, mostly at home. A very religious family, the Pateks — Fred, wife Jerri, and daughter Heather — supported Kim with prayer and frequent trips to Hickman Mills Church of Christ. Former teammates and the Baseball Assistance Team (BAT) also helped with medical bills. After Kim died in 1995, Fred isolated himself for several more years. “I was in a shell, hurt, sad, angry, and you don’t understand,” he reflected. “The only thing I can tell you is that I was never the same; I was totally different.”60 Soon after, Heather gave birth to Jordan, the Pateks’ first granddaughter. “She saved my life,” Fred exclaimed. “She’s the one God gave me to keep me going.”61

And going he did; he formed the Kim Patek Foundation to fight paralysis and raised funds for the Spinal Cord Society through fishing and golf tournaments as well as charity basketball games. Besides coaching American Legion ball, he worked with Little League teams for over 30 years.62 Health issues caught up with him in 2005, when he had a cobalt shoulder replacement for all those throws he made as a player. Months later he had triple-bypass surgery on his heart.63 By 2017 he decided to retire from coaching completely and enjoy his family and grandchildren in Lees Summit, Missouri, near Kauffman Stadium.64

Thankfulness filled Patek’s heart after that day in 1971 when he took inventory of his life. “If it hadn’t been for the good lord, I wouldn’t have made it,” he reflected. “And I could see that in my whole life, where God was taking care of me, he was looking out for me. That’s the only reason I ever made it to the big leagues. … I can see God’s hand in all of that.”65 Some of “that” includes many honors Patek received in retirement. Bill James rated him the 14th greatest Royal. A number of halls of fame inducted him, including the Royals Hall of Fame (1992) and the Missouri Sports Hall of Fame (1999). In 2018 the San Antonio Sports Hall of Fame nominated Patek for membership. Despite these earthly recognitions, Fred Patek might value his highest honor as induction into his Fathers Hall of Fame.

Last revised: December 26, 2018

This biography appears in “Kansas City Royals: A Royal Tradition” (SABR, 2019), edited by Bill Nowlin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Fred Patek, telephone interview with author, September 25, 2018. (September 25 interview).

2 Dave Anderson, “Patek Adds 2 Inches as an Angel,” New York Times, March 13, 1980: D19.

3 Ibid.

4 Dan Holmes, “Little Freddie Patek Made Immediate Impact on Royals,” Baseball for Egg Heads, April 25, 2012. baseballegg.com/2012/04/25/little-freddie-patek-made-immediate-impact-on-royals/, retrieved July 17, 2018. Rick Monday, the first overall pick posted a 33.1 WAR, Patek produced a 24.1 WAR.

5 Fred Patek, telephone interview with author, November 2, 2018. (November 2 interview).

6 September 25 interview.

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.

9 Joe McGuff, “Big Heart Chief Ingredient in Tiny Patek’s Comeback,” The Sporting News, May 20, 1972: 4.

10 Bill Ballew, The Pastime in the Seventies: Oral Histories of 16 Major Leaguers (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland Publishing, 2002), 166.

11 Alan Cohen, “The Hearst Sandlot Classic: More than a Doorway to the Big Leagues,” Baseball Research Journal, Society for American Baseball Research, Fall 2013: 27.

12 Alan Cohen, “The Hearst Sandlot Classic — Part Nine: 1963-1964. One Little Guy and One Big Guy,” June 28, 2016. linkedin.com/pulse/hearst-sandlot-classic-part-eight-1963-1964-alan-cohen?articleId=6153567872460341249, retrieved September 13, 2018.

13 September 25 interview.

14 November 2 interview.

15 Bill Ballew.

16 Joe McGuff, “Big Heart.”

17 September 25 interview.

18 “International Items,” The Sporting News, July 29, 1967: 31.

19 Les Biederman, “Veale Missed Turn,” The Sporting News, June 29, 1968: 18.

20 United Press International, “Pirates Win by 13-2 on Veale’s 6-Hitter,” New York Times, June 16, 1968: S4.

21 September 25 interview.

22 Charley Feeney, “‘They Treat Me Just Like a Kid!’ Fumes Patek, the Unhappy Buc,” The Sporting News, November 21, 1970: 47.

23 Les Biederman, “Buccos Used the Broom, Now Kids Can Kick Up Some Dust,” The Sporting News, November 2, 1968: 38.

24 September 25 interview.

25 Charley Feeney, “Bucs Hold Pat Hand at SS, It’s Patek,” The Sporting News, November 22, 1969: 36.

26 Charley Feeney, “ ‘They Treat Me …’”

27 Ibid.

28 Dick Young, “Young Ideas: Cardenas Tosses Barb at Reds,” The Sporting News, April 12, 1969: 14.

29 Jerome Holtzman, “Vet Ump Barlick May Retire,” The Sporting News, October 3, 1970: 6.

30 Charley Feeney, “Weather Torrid … So Are Alley, Patek,” The Sporting News, September 6, 1969: 18.

31 Paul Cour, “Padres May Give Zoilo New Shot at Shortstop,” The Sporting News, November 14, 1970: 57.

32 September 25 interview.

33 Charley Feeney, “Johnson Puts New Sheen on Corsair Hill Staff,” The Sporting News, December 19, 1970: 41.

34 Charley Feeney, “‘They Treat Me …’”

35 Charlie Smith, “Swifties Otis, Patek Carry Royals’ Title Bid,” The Sporting News, March 4, 1972: 21.

36 The Official Site of the Kansas City Royals. History of Kauffman Stadium. mlb.mlb.com/kc/history/ballparks.jsp, retrieved August 29, 2018.

37 September 25 interview.

38 Joe McGuff, “Tiffs with Players, Press End McKeon Reign at K.C.,” The Sporting News, August 9, 1975: 9.

39 Sid Bordman, “Tiny Patek a Mighty Atom Fueling Royals’ Late Surge,” The Sporting News, August 30, 1975: 11.

40 Joe McGuff, “Patek Sheds Suet and Scoots in Old-Time Style,” The Sporting News, July 10, 1976: 14.

41 Curt Nelson, “This Date in Royals History — October 1, 1976,” Royals Then, Now & Forever: The Official Blog of the Royals Hall of Fame, royalshof.mlblogs.com/2009/10/01/this-date-in-royals-history-october-1-1976/#comment-36, retrieved September 3, 2018.

42 Baseball Reference salary data 1977-79 for Fred Patek, baseball-reference.com/players/p/patekfr01.shtml, retrieved July 14, 2018.

43 Bob Fowler, “Thor Removing Thunder from Enemy Bats,” The Sporting News, July 9, 1977: 3.

44 Herman Weiskopf, “The Week (June 19-25),” Sports Illustrated, July 3, 1977: 45.

45 Dave Anderson, “The Shortest Shortstop: 5-4 and 140,” New York Times, October 7, 1977: 33.

46 Matt Fulks, “Composure: Fred Patek,” C You in the Major Leagues Foundation, August 31, 2017, cyouinthemajorleagues.org/composure-fred-patek/, retrieved October 12, 2018.

47 Rustin Dodd, “40 Years Ago, George Brett Punched Graig Nettles in the ALCS. Then the Game Continued,” Kansas City Star, October 18, 2017, kansascity.com/sports/mlb/kansas-city-royals/article179483061.html, retrieved September 20, 2018.

48 Joe Posnanski, “From the Archives: Royals and Yankees Didn’t Play Nice in ’77,” Kansas City Star, April 22, 2015, kansascity.com/sports/mlb/kansas-city-royals/article19219905.html, retrieved September 20, 2018.

49 Dick Miller, “Patek ‘Grows’ as Angel Shortstop,” The Sporting News, March 8, 1980: 35.

50 Del Black, “Washington Earning Royal Raves,” The Sporting News, September 22, 1979: 7.

51 Dick Young, “Young Ideas,” The Sporting News, December 22, 1979: 16.

52 Matt Fulks, “Composure: Fred Patek.”

53 November 2 interview. See also Charlie Smith, “Former Royal Patek Proud to Be Among Ryan Victims,” TulsaWorld.com, September 23, 1989, tulsaworld.com/archives/former-royal-patek-proud-to-be-among-ryan-victims/article_f2db3503-08c2-55c1-8c73-e119d521546c.html, retrieved October 2, 2018.

54 “Pro Transactions. Baseball,” The Sporting News, April 24, 1982: 33.

55 Keith Thursby, “Viewpoint: A Look at Those Colorless Color Commentators,” Orange Coast Magazine (Irvine, California), July 1982: 138.

56 November 2 interview.

57 Barry Lewis, “Rangers Won’t Keep Carpenter,” TulsaWorld.com, January 12, 1990, tulsaworld.com/archives/rangers-won-t-keep-carpenter/article_d165aaf6-82f6-5dbc-b7d9-6c6aac3f9558.html, retrieved August 12, 2018.

58 Charlie Smith, “Former Royal Patek.”

59 Ira Berkow, “Baseball; For Pateks, the Safety Net Fails,” New York Times, March 14, 1993: 81.

60 Matt Fulks, “Composure: Fred Patek.”

61 Ibid.

62 Bill Althaus, “My Idol Patek Giving Back to Young Players,” The Examiner (Eastern Jackson County, Missouri), July 29, 2009, examiner.net/article/20090729/NEWS/307299719, retrieved October 23, 2018.

63 Matt Fulks, “Composure: Fred Patek.”

64 November 2 interview.

65 September 25 interview.

Full Name

Frederick Joseph Patek

Born

October 9, 1944 at Oklahoma City, OK (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.