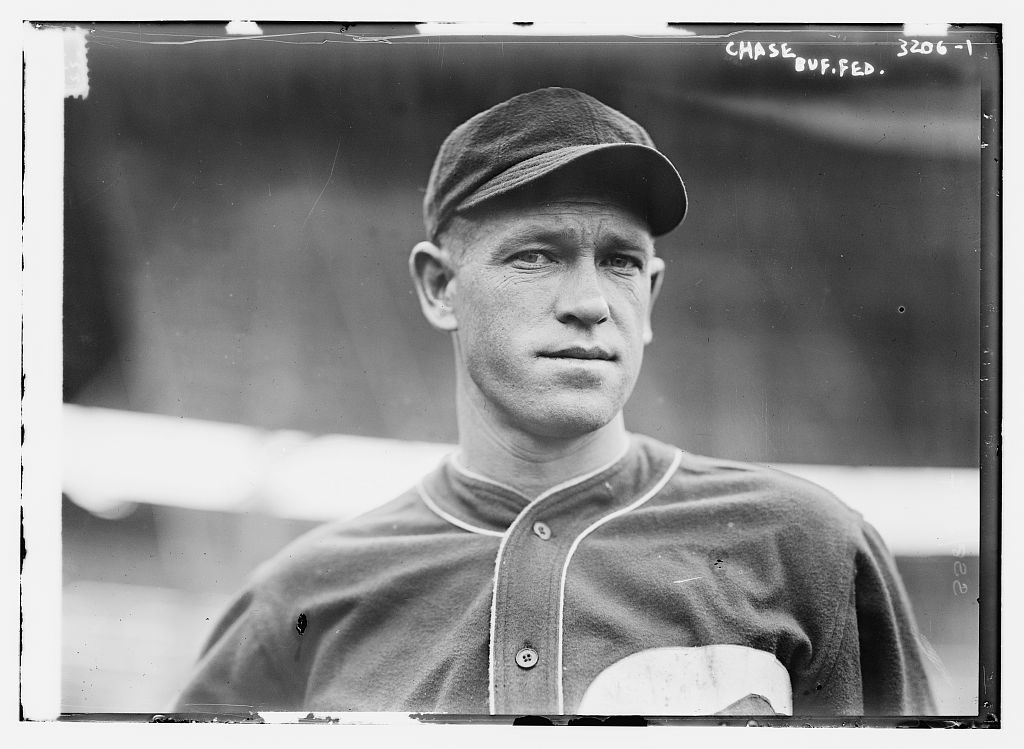

Hal Chase

Hal Chase, whose big league career lasted from 1905 to 1919, was the most notoriously corrupt player in baseball history. He was also, according to many of those who saw him play, the greatest defensive first baseman ever. A cocky, easygoing Californian, Chase was the first homegrown star of the New York Highlanders (later the Yankees), but he wore out his welcome with them, as he did with just about every other team he played for during his fifteen years in the major leagues.

Hal Chase, whose big league career lasted from 1905 to 1919, was the most notoriously corrupt player in baseball history. He was also, according to many of those who saw him play, the greatest defensive first baseman ever. A cocky, easygoing Californian, Chase was the first homegrown star of the New York Highlanders (later the Yankees), but he wore out his welcome with them, as he did with just about every other team he played for during his fifteen years in the major leagues.

Yet there was something about “Prince Hal,” as he was perhaps inevitably nicknamed, some combination of athletic grace, back-slapping charm, and apparent sincerity, that convinced any number of hard-bitten baseball men — men who should have known better — to take a chance on him. Long after his alleged transgressions had come to light, moreover, he was recalled by many of his peers — including Babe Ruth, Pants Rowland, Ed Barrow, Cy Young, and Bill Dinneen, to name just a few — as the best first baseman they had ever seen. Yet when he died, a penniless derelict, in 1947, he left behind two shattered marriages, an estranged son, and one of the great unfulfilled careers in baseball history. Today he is remembered as the poster boy for an era when gambling and throwing games seem to have been much more common than anyone was willing to admit.

Harold Homer Chase always marched to the beat of a different drummer. He was born in Los Gatos, California, on February 13, 1883, the fourth son of James and Mary Chase, natives of Maine who had emigrated to California, where a number of relatives had already settled, in the late nineteenth century. The Chase family was involved in the lumber industry, but young Hal never evinced much interest in the family business. Instead, at an early age, he decided that his remarkable athletic skills would be his meal ticket. As a youth he played on various semipro teams in and around San Jose and eventually enrolled in nearby Santa Clara College, which at that time was a West Coast collegiate baseball power.

At Santa Clara, Chase supposedly studied engineering, though there is no evidence to suggest he ever set foot in a classroom. He was something of an oddity in that he frequently played second base and catcher even though he threw left-handed, but his athletic ability was obvious — so much so that in 1903 the Los Angeles Angels of the Pacific Coast League signed Chase to his first professional contract.

- Learn more: Click here to view SABR’s Eight Myths Out project on common misconceptions about the Black Sox Scandal

Chase spent the 1904 season with the Angels, playing first base, batting a solid but unspectacular .279, and catching the eyes of scouts from the eastern major league clubs. When the Highlanders drafted him, the Angels threatened to rupture the newly signed peace agreement between the PCL and the rest of organized baseball rather than give up their promising young star-in-the-making, but eventually cooler heads prevailed. Chase reported to the Highlanders and was immediately installed as the starting first baseman.

The Highlanders were an appropriate team for Chase, if only because their owners personified the dubious morality of early twentieth century New York. Frank Farrell was the proprietor of the most famous illegal casino in the city; his partner Big Bill Devery was a notoriously corrupt police captain and Tammany Hall functionary. Their young star took to New York like the proverbial duck to water. He quickly became a fixture in Broadway’s sporting and theatrical demimonde, rubbing shoulders and raising glasses with the likes of George M. Cohan, Al Jolson, and Willie Hoppe.

It took eight and a half seasons for Chase to wear out his welcome in New York, but during that time he established himself as one of the biggest stars in baseball. Those seasons had highs, though they were mostly individual rather than collective: the Highlanders went through six managers, including Chase himself, and only twice posted winning records, but Prince Hal finished among the AL top ten four times in RBI, three times in batting average, and twice in stolen bases. In addition, he earned a reputation as perhaps the best batter in the league at executing the hit-and-run. For the most part, though, Chase was better known for his defense, and his relaxed ethical standards, than his offense.

Right from the start, his glovework was a revelation. Longtime baseball men were astonished at how far off the bag he played, his casual one-handed catches, and his catlike pounces on sacrifice bunt attempts. Soon, however, the whispers began that Chase, while undeniably talented, was a selfish prima donna who was a disruptive force on the ballclub. Once, when a reporter complimented him on a particularly outstanding play, he grinned and replied, referring to his less-talented teammates, “I could make plays like that every day, only I am afraid to turn the ball loose because I might hit one of those dopes in the head.”

More seriously, in 1907 he threatened to jump to the outlaw California State League until Farrell raised his salary. In September 1908 he left the Highlanders and returned to California, reportedly upset that shortstop Kid Elberfeld, rather than Chase, had been named to replace Clark Griffith as interim manager of the struggling Highlanders. Two years later he left the team during a Midwestern road trip and returned to New York to demand that Farrell fire manager George Stallings. The fiery Stallings responded by accusing Chase of “laying down” on the team. The owner sided with his star player, dismissing Stallings and appointing Prince Hal in his stead. His teammates were less than thrilled; recalling the episode years later, Jimmy Austin commented, “God, what a way to run a ballclub!”

Chase’s tenure as manager was not a success, and he was allowed to resign following the 1911 season. He managed to stay out of trouble until early in the 1913 campaign, when he ran afoul of the Yankees’ new manager, Frank Chance. “The Peerless Leader,” whom Farrell had hired with great fanfare, told two reporters that Chase was “throwing down me and the team.” Farrell finally agreed that Prince Hal had to go, and traded him to the White Sox for first baseman Babe Borton, who batted .130 in 33 games as Prince Hal’s replacement, and infielder Rollie Zeider, who was troubled by foot problems. Both were gone after the season; reporter Mark Roth wrote caustically that “The Yankees traded Chase to the White Sox for an onion and a bunion.”

Chase spent scarcely more than one full season in Chicago before jumping to Buffalo of the upstart Federal League. He turned the tables on the White Sox by invoking the standard baseball contract’s “ten-day clause,” by which clubs were required to give an unwanted player ten days’ notice before terminating his contract. Chase saw no reason why the ten-day clause shouldn’t work the other way. Organized baseball, needless to say, was outraged, but the ensuing legal wrangle ended with a judge declaring that the structure of organized baseball was “a species of quasi-peonage unlawfully controlling and interfering with the personal freedom of the men employed.”

Chase was one of the biggest stars in the Federal League, batting .347 over the remainder of the 1914 campaign and leading the league with 17 home runs in 1915, but when the Feds went belly-up following the 1915 season his reputation as a troublemaker ensured that no American League team would have him. He finally caught on with the National League Cincinnati Reds as the 1916 season began and went on to enjoy his finest season in the majors, leading the NL in batting (.339) and hits (184) and finishing second in RBI (82) and slugging percentage (.459) and third in total bases (249).

Two years later, however, he was in trouble again. Christy Mathewson had become manager of the Reds, and Matty suspended his old friend in August 1918 for offering bribes to teammates and opponents, including Giant pitcher Pol Perritt, to influence the outcome of games on which he had bet.

At a postseason hearing before NL president John Heydler, three Reds players — Jimmy Ring, Greasy Neale, and Mike Regan — testified against a defiant Chase. But neither Mathewson, serving with the military in France, nor Perritt was present, and John McGraw himself testified that he could not confirm the allegation that Chase had offered Perritt a bribe. A frustrated Heydler had no choice but to let Chase off the hook.

To the surprise of practically no one, the newly exonerated Prince Hal quickly signed on with McGraw’s Giants, who were in dire need of a first baseman. “I have found him a most agreeable chap, and I am sure we will get along without a hitch,” predicted the manager in the spring. (Adding to the intrigue, Mathewson returned from France and also joined the Giants as a coach.)

McGraw’s optimism was, to put it mildly, misplaced. By September 1919 Chase was on the sidelines, ostensibly because of an injured wrist but in reality because he had once again, along with Giant third baseman Heinie Zimmerman, been attempting to bribe teammates. Chase never played in the majors again.

In the spring of 1920 he was back in California playing semipro ball when his former Cincinnati teammate Lee Magee revealed that he and Prince Hal had conspired to throw games during the 1918 season. In August Chase was also accused of attempting to bribe Pacific Coast League players, for which he was banned from organized baseball in his native state. But even these bombshells were overshadowed when news of the Black Sox Scandal began to leak out in September. Chase was eventually indicted as an alleged middleman in the fix, though he avoided extradition to Chicago, and thus his role in the scheme was never definitively established. Rube Benton testified that Chase had won $40,000 betting on the 1919 World Series, though his testimony was later called into question. Curiously, however, baseball commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis never officially expelled Chase from organized baseball.

Prince Hal spent most of the 1920s playing semipro ball in Arizona, bouncing among teams representing Nogales, Williams, Jerome, and Douglas, to which he lured Black Sox pariahs Chick Gandil, Buck Weaver, and Lefty Williams. He was in the latter town in 1926 when the radio evangelist Aimee Semple McPherson turned up there, claiming to have been abducted by Mexican bandits. It was eventually revealed that she had run off with her radio engineer, and reporter S. L. A. Marshall later claimed that Chase had contemplated blackmailing Sister Aimee, threatening to reveal that she had disappeared to have an abortion, though no evidence exists to corroborate this story. Chase moved on to an El Paso, Texas, team in 1927, and spent the rest of the 1920s playing for various semipro clubs in California while also prospecting for gold in the Sierra Nevada mountains.

Eventually, of course, the years of carousing began to take a toll, as did a 1926 car accident which severed an Achilles tendon. By December 1933, when he was rediscovered in Tucson by the New York writers accompanying the Columbia football team to the Rose Bowl, Chase seems to have been little more than a shambling derelict.

The last fifteen years of his life were miserable. Chase ended up living on the Williams, California, ranch of his sister Jessie and her husband, Frank Topham. Topham so loathed his brother-in-law that he refused to allow him in the house and built him his own cabin on the property. Chase granted interviews that were published in The Sporting News while he was hospitalized with various health problems in 1941 and again in 1947. He must have sensed that he was running out of time, for in these interviews he seemed desperate to clear his name. He again denied having had a role in arranging the Black Sox fix, though he admitted that he had known about it in advance and expressed regret at having kept silent about it: “I did not want to be what I then called a ‘welcher.’ I had been involved in all kinds of bets with players and gamblers in the past, and I felt this was no time to run out.” He added, “I’d give anything if I could start in all over again…. I was all wrong, at least in most things, and my best proof is that I am flat on my back, without a dime.” But, he still insisted, “I never bet against my own team.” He died on May 18, 1947, and was buried in Oak Hill Memorial Park in San Jose.

This biography originally appeared in SABR’s “Deadball Stars of the American League (Potomac Books, 2006), edited by David Jones.

Sources

Donald Dewey and Nicholas Acocella, The Black Prince of Baseball: Hal Chase and the Mythology of the Game. Sport Classic Books, 2004.

Martin Donell Kohout. Hal Chase: The Defiant Life and Turbulent Times of Baseball’s Biggest Crook. McFarland, 2001.

Lawrence S. Ritter. The Glory of Their Times: The Story of the Early Days of Baseball Told by the Men Who Played It. Collier, 1966.

Full Name

Harold Homer Chase

Born

February 13, 1883 at Los Gatos, CA (USA)

Died

May 18, 1947 at Colusa, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.