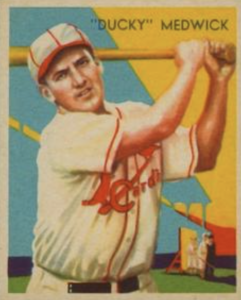

Joe Medwick

Ten times he was named to the National League All-Star team; he won the circuit’s Most Valuable Player Award in 1937; and in that same year he became the league’s last batter (as of 2013) to win the Triple Crown by leading the loop in batting average, home runs, and runs batted in during the same season. Yet perhaps Joe Medwick is better remembered for being banished from a World Series game by Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis than for his exploits on the field.

Ten times he was named to the National League All-Star team; he won the circuit’s Most Valuable Player Award in 1937; and in that same year he became the league’s last batter (as of 2013) to win the Triple Crown by leading the loop in batting average, home runs, and runs batted in during the same season. Yet perhaps Joe Medwick is better remembered for being banished from a World Series game by Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis than for his exploits on the field.

It was the seventh and deciding game of the 1934 World Series in Detroit between the St. Louis Cardinals and the hometown Tigers. Behind the stellar pitching of Dizzy Dean, who with some justification proclaimed himself the greatest pitcher in the world, the Gas House Gang were leading 7-0 in the sixth inning. But they wanted more. Pepper Martin led off the top of the frame with a single to left and made it to second on Goose Goslin’s misplay of the ball. Jack Rothrock and Frankie Frisch both flied out. Up came Medwick with Martin on second and two out. Joe slashed a long hit against the right-field bleachers, knocking in Martin. As Medwick slid into third base, Marvin Owen, the Tiger third sacker, dug his foot into Joe’s leg. The hot-tempered Cardinal, still lying on the ground after the slide, retaliated by kicking Owen in the stomach with both spiked shoes. For a moment it appeared that a fight would break out, but players and umpires quickly separated the potential combatants and the game continued. Ripper Collins batted Medwick home with a single to make the score 9-0. The half-inning ended when Bill DeLancey was thrown out at first base after he and the catcher both missed strike three.

When Medwick took the field in the bottom of the sixth, Detroit fandom greeted him with resounding boos and a barrage of missiles hurled into left field. Mostly apples, oranges, and grapefruit, but also a few pop bottles were thrown onto the playing field. No bottles hit a player, and Medwick and fellow outfielders Ernie Orsatti and Rothrock started playing catch with some of the fruit on the field, further incensing the crowd. That Medwick seemed to be not at all intimidated by the barrage made the crowd even more upset. The umpires halted play, and sent workers out with burlap bags to pick up the debris. Three times the umpires and Detroit manager Mickey Cochrane called for order, to no effect. Each time Medwick attempted to take the field; the assault began anew. When it appeared that all the fruit and vegetables in the stands had already been thrown, someone discovered that hot-dog buns and folded-up newspapers could be used as missiles and the assault began anew. The booing had continued unabated the whole while. After a delay of 17 minutes, Commissioner Landis called Owen, Medwick, and the two managers to his box and held court. The potentate asked Medwick if he had any reason to kick Owen. When Medwick replied in the negative, Landis asked why he had done it. Joe replied, “It was just one of those things that happen in a ballgame.”1

Landis immediately thumbed him out, and Medwick was escorted from the field by five policemen. The commissioner defended his actions: “I saw what Medwick did and I couldn’t blame the Detroit crowd for what it did. I did the proper thing.” He said he took the action “to protect the player from injury and permit the game to proceed.”2 To some it seemed that Landis had set a dangerous precedent. What could prevent a future crowd from rioting against the star of a visiting club and having him removed? However, that has not happened. A more just decision might have been to forfeit the game if Detroit management could not maintain order and protect the safety of the players. The problem is that such a decision might have provoked a full-scale riot. As it was, Chick Fullis replaced Medwick in left field and the game continued to its conclusion, with the Cardinals posting an 11-0 victory and winning the world championship.

Joseph Michael Medwick was born November 24, 1911, in Carteret, New Jersey, the fourth child of Elizabeth and John Medwick, a carpenter. Joe was of Hungarian descent, both of his parents having been born in the Austro-Hungarian monarchy and having immigrated to the United States in 1893. According to his obituary, Joe was a four-sport star at Carteret High School, participating in track, football, basketball, and baseball. He won all-state honors as a high-school halfback and had many offers of college scholarships to play football. However, he preferred baseball. As a teenager, Joe was signed off the New Jersey sandlots by the St. Louis Cardinals organization.

In 1930 the 18-year-old outfielder made his professional baseball debut for the Scottdale, Pennsylvania, Scotties, an affiliate of the Cardinals in the Class C Middle Atlantic League, playing under the name Mickey King in order to protect his amateur status. Stockily built at 5-feet-10 and 187 pounds, the youngster hit and threw right-handed. And how he hit! In 75 games he clubbed 22 home runs and led the league with a .419 batting average and a .750 slugging percentage. Many observers declared that he was the best young ballplayer ever to come into the Middle Atlantic League. This stellar performance earned Medwick a promotion to the Houston Buffaloes club in the Class A Texas League, skipping Class B ball entirely. In 1931 Medwick led the league in total bases, but he really starred in 1932, when he led the circuit in slugging at .611 and was second in batting average with .354. His 342 total bases were only two fewer than Hank Greenberg’s league-leading output. In addition, he had a strong and accurate throwing arm and was considered the best all-around outfielder in the Texas League.

While playing with Houston, Medwick acquired the nickname Ducky. Some say it was because he waddled like a duck when he walked. His teammates picked up on it and started calling him Ducky or even worse Ducky Wucky. Joe detested the name, but it caught on and for years sportswriters routinely referred to him as Ducky. Medwick much preferred to be called Muscles and induced some of his teammates to use that appellation.

With three years of minor-league experience behind him, Joe made his major-league debut with the parent St. Louis Cardinals on September 2, 1932. He went hitless in his first game, but had a run batted in on a sacrifice fly and scored once himself after getting on base with a force out. Despite this inauspicious beginning, Medwick had an outstanding month. In 26 games that September, Medwick hit .349, slugged .538, and had an on-base-plus-slugging percentage (OPS) of .905. He was well on his way to stardom.

During the next four seasons, Medwick twice led he league in total bases, and once each in hits, doubles, triples, and runs batted in. In 1936 he set a National League record with 64 doubles, a mark that has not been matched as of 2013. The year 1936 also saw his marriage on August 24 in St. Louis to 19-year-old Isabelle Heutel. Then came that magical season of 1937, when he led in hits, doubles, home runs, batting average, slugging percentage, on-base plus slugging, runs scored, and runs batted in – all in the same year. Naturally, he won the National League’s Most Valuable Player Award in 1937. In eight full seasons and two partials from 1932 to 1940, Joe never hit less than .300 for the Cardinals.

At that time the Cardinals were notorious for penurious treatment of players. In Joe’s opinion he was the best player in the league and deserved more pay. Contract negotiations were strenuous, but with the reserve clause in effect Medwick had little leverage. In 1938 the outfielder had received $20,000. Despite leading the league in runs batted in that season, Medwick was forced to accept a cut to $18,000 for 1939. Relations between the club and its star became strained. To Joe Medwick, baseball was all about “Base hits and Buckerinoes.” He delivered with base hits, and he expected the club to deliver big bucks. Joe did not have an engaging personality, to say the least. Even some of his teammates did not like him. Cardinals’ owner Sam Breadon had little patience for impudent hired hands. Eventually, he convinced general manager Branch Rickey that the slugger was expendable. On June 12, 1940, Rickey traded Medwick along with pitcher Curt Davis to the Brooklyn Dodgers for four players and a sum variously reported as $125,000 or $200,000.

On June 19 in his sixth game for the Dodgers, Medwick faced his former team. Once again Joe became the central figure in a contentious ball field incident that threatened to become even more serious than the event in the 1934 World Series. Batting cleanup for the Dodgers, Medwick faced his former teammate Bob Bowman in the first inning, with two runs already in and a runner on base. Bowman’s first pitch was a high, hard one on the inside. It struck Medwick in the head, knocking him unconscious. The Dodgers rushed out of their dugout, intent on wreaking vengeance on Bowman, who they believed had beaned the outfielder deliberately. Some tried to punch him. Even Larry McPhail, the Dodgers president, got in a swing, knocking off the pitcher’s hat. Medwick was carried off the field on a stretcher and taken to the Caledonian Hospital, where it was discovered that he had a concussion but no fracture. He tried to get out of his hospital bed and go after his assailant. Meanwhile, Bowman was removed from the game and escorted by policemen back to his hotel.

One reason the Dodgers were so irate about this incident is that Bowman had been in a verbal confrontation with Medwick and Dodgers manager Leo Durocher in the hotel the previous morning. The pitcher had shouted, “I’ll take care of you! I’ll take care of both of you.”3 Bowman said he meant that he would hold them hitless in the game. The Dodgers’ version was that the pitcher had threatened them with beanballs. Acting on this belief, McPhail appealed fruitlessly to National League President Ford Frick to ban Bowman from baseball for life. Further he attempted to have Bowman arrested for assault. The Brooklyn district attorney investigated and found no evidence of criminal intent on the pitcher’s part.

Medwick was out of the hospital in four days and quickly back in the lineup, missing far less than the three weeks he was expected to be on the shelf. He was named to the National League All-Star team for the seventh consecutive season. Starting the game in left field, he was hitless in two times at bat before departing in favor of Jo-Jo Moore in the NL’s 4-0 victory. One result of the beaning was a renewed interest in the use of batting helmets. Many players were opposed to the use of helmets, fearing that such would make them seem less daring than they wished to appear. Furthermore, the fans liked their baseball rough and reckless. But some fans realized they can’t cheer the exploits of a player who lies in a hospital bed. In July Spalding Sporting Goods began advertising a batting helmet with ear flaps. However, it was not until 1971 that it became mandatory for all new major leaguers to wear helmets, and even then, veterans were exempted through a grandfather clause.

After the beaning, Medwick played eight more years in the major leagues, not hitting with quite the power he had shown previously, but still topping the .300 mark several times, including .337 in 1944. During these years he played variously with Brooklyn, the New York Giants, and the Boston Braves, before closing out his major-league playing career with the Cardinals on July 25, 1948, at the age of 36. But he was not done with baseball. He finished the 1948 season with Houston in the Texas League. From 1949 through 1951 he was a minor-league player-manager, with such clubs as the Miami Beach Flamingoes and the Tampa Smokers of the Florida International League and the Raleigh Capitals of the Carolina League.

After waiting impatiently for 20 years, Medwick was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown in 1968. His long wait may have been caused by the antagonism felt toward him by many baseball writers, whom he often dismissed rudely when they approached him for interviews. By 1968 this animosity had been largely forgotten and he received votes from 84.8 percent of the writers casting ballots.

On March 21, 1975, Joseph Medwick died at St. Petersburg, Florida, of a heart attack. He had been working as a batting instructor in the Cardinals’ spring-training camp. He was 63 years old. The great player was survived by his widow, Isabelle; a son Joe Medwick, Jr. of Key Largo, Florida; and a daughter, Susan Medwick George of St. Louis. His body was taken back to Missouri and he was buried in St. Lucas Cemetery in Sunset Hills, a suburb of St. Louis.

Many honors came to Medwick posthumously. It’s too bad the fiercely proud competitor could not have lived to relish them. At the turn of the century, several groups published lists of the country’s most outstanding players. In 1999, Joe was ranked 79th on The Sporting News list of Baseball’s Greatest Players. A poll of SABR members ranked Medwick 100th. Sports Illustrated named him the second-best baseball player of the century from New Jersey and the seventh-greatest overall from the Garden State.

A version of this biography appeared in “The 1934 St. Louis Cardinals The World Champion Gas House Gang” (SABR, 2014), edited by Charles F. Faber.

Sources

Graham, Frank, The Brooklyn Dodgers: An Informal History (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1945).

Lieb, Frederick G., The St. Louis Cardinals: The Story of a Great Ball Club (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1945).

Stockton, J. Roy, The Gashouse Gang and a Couple of Other Guys (New York: A.S. Barnes & Company, 1945).

Notes

1 J. Roy Stockton, The Gashouse Gang and a Couple of Other Guys (New York: A.S. Barnes, 1945), 131.

2 Frederick G. Lieb, The St. Louis Cardinals: The Story of a Great Ball Club (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1945), 174.

3 Frank Graham, The Brooklyn Dodgers: An Informal History (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1945), 185.

Full Name

Joseph Michael Medwick

Born

November 24, 1911 at Carteret, NJ (USA)

Died

March 21, 1975 at St. Petersburg, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.