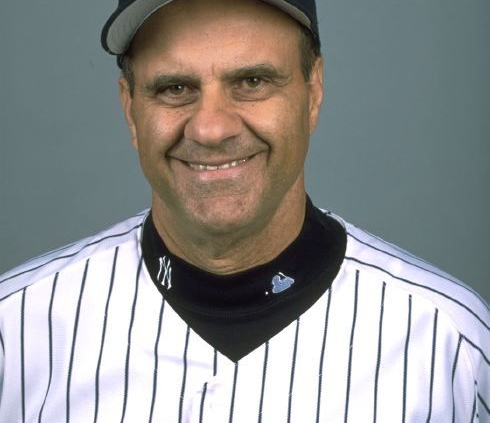

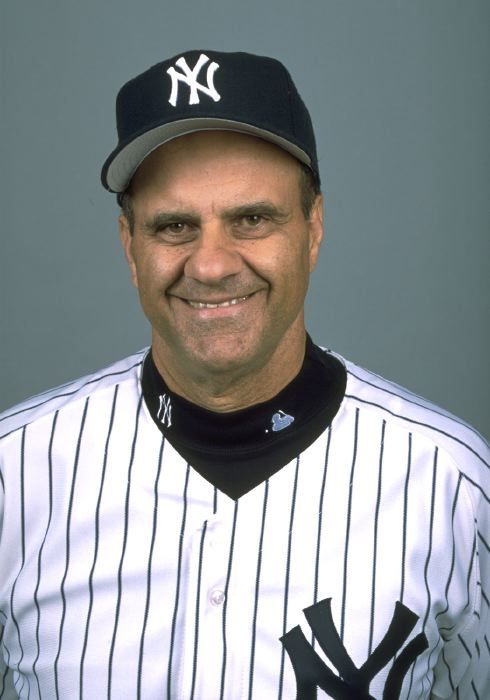

Joe Torre

Baseball is a game of numbers, so it is fitting to begin this story with the number Four Thousand Two Hundred Seventy-Two.

Baseball is a game of numbers, so it is fitting to begin this story with the number Four Thousand Two Hundred Seventy-Two.

No one had ever taken longer to get to the World Series – 4,272 major-league games as player and manager before his first Series game in 1996. As Joe Torre stated in Chasing the Dream, “It had taken getting traded twice and fired three times. Both my parents had died years before they could have seen me celebrate the victory. And in the end, it had taken the most emotional twelve months of my life: the birth of my daughter Andrea Rae; the shocking death of my brother Rocco; and a life-saving transplant for (brother) Frank on the eve of the clinching game of the World Series. I never expected that chasing the dream would bring me to so many magical moments, or that the road to get there would be so long and so often painful.”1

Seventeen years after that first World Series game, on December 9, 2013, Torre was notified that he was a unanimous selection of the Expansion Committee to be enshrined at Cooperstown.

That first World Series in 1996 was the beginning of a streak of 14 consecutive trips (12 with the Yankees and two with the Dodgers) to the postseason for Joe Torre. His teams during those years won 12 divisional championships (including nine consecutive from 1998 through 2006), six American League pennants, and four World Series championships. During the Yankees’ four World Series championships in five years (1996, 1998-2000), his teams, at one point, won 14 consecutive World Series games. His record with the Yankees was 1,173-667, and after leaving the Yanks, he managed the Dodgers to a record of 259-227 that included his last two divisional championships. As manager, Joe had a simple philosophy which can be summed up as follows: “Even though I have loyalty to people, you have to be loyal to twenty-five players as opposed to one.”2

Joseph Paul Torre, born on July 18, 1940, in the Marine Park section of Brooklyn, was the youngest of five children born to Joe Torre Sr. and his wife Margaret Rofrano Torre, who had come to the United States from Salerno, Italy at the age of 8. Joe’s father was a New York City police detective and things around the Torre household in Brooklyn were almost always tense, especially between Joe’s parents. Joe’s father also did some scouting for the Braves and Orioles. He had gotten his start in scouting with the Boston Braves, working out a deal with the team when they signed Joe’s brother Frank in 1950. Joe’s father passed away in January 1971.

Speaking of his father Joe said, “Although he never physically hurt me, he verbally abused me often.” On the other hand, Joe’s mother, who was physically abused by his father, was “a loving, stabilizing influence, who always was there for me.”3

Later in life, remembering the pain endured by his family in his youth, Torre began the Safe at Home Foundation for victims of domestic violence.4 Since its inception in 2002, the Foundation has educated thousands of students, parents, teachers, and school faculty about the devastating effects of domestic violence.5

After suffering years of abuse, Joe’s mother divorced his father in 1951, when Joe was 11. Brother Rocco, 11 years older than Joe, was a New York policeman, and Frank, eight years older than Joe, was a ballplayer in the Braves organization during Joe’s formative years. It was to them that Joe turned for guidance. His sisters Rae and Marguerite, a nun who became principal at Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Elementary School in Queens, were also big baseball fans.

One thing about Joe that did change during the summer of 1951 was his body. Frank was playing for the Denver Bears of the Class A Western League and Joe went for a visit. Joe ate incessantly during the trip and, as he noted, “I went to Denver as something of an average-sized 10-year-old and came home a little more than a month later as an 11-year-old blimp.”6

Baseball was an important part of Joe’s life from a very early age, and it wasn’t long before he got noticed.

Torre had been tearing things up for years and was a favorite of Vincent “Cookie” Lorenzo, who headed up the Sandlot League at Brooklyn’s Parade Grounds for more than 60 years. Lorenzo first noticed Torre in 1954 when the 14-year-old, much shorter than his adult height of 6’ 2”, slammed three doubles in a game being umpired by Lorenzo. Lorenzo once commented that Torre was “A fire hydrant, short and stocky, but can he hit.”7

Torre’s sandlot team, the Cadets, were managed by Jim McElroy, and played most of their games at Brooklyn’s Parade Grounds, a complex near Brooklyn’s Prospect Park that had no less than 13 fields. In those days with the Cadets and in his last two years at his high school, St. Francis Prep, Joe Torre rotated between first base and pitching, as had his brother Frank. He is a member of the Parade Grounds Hall of Fame.

On August 26, 1958, the young sandlotter from Brooklyn took to the field at New York’s Polo Grounds. The all-but-deserted former home of the New York Giants was hosting the annual Hearst Sandlot Classic between the U. S. All-Stars and the New York All-Stars. The Brooklyn Cadets of the Kiwanis League were represented by their slugging first baseman, Joe Torre.

Torre’s brother Frank had played in the Hearst game back in 1949. Joe started the 1958 game on the bench and went 0-for-1 after entering the game. There were scouts from all 16 major-league clubs at the contest, but Torre didn’t get a sniff. He was overweight and slow afoot; nobody was interested. Even batting .647 in the 1958 All-American Amateur Baseball Association tournament in Johnstown, Pennsylvania did not change the consensus that he was too fat, too slow, and too uncoordinated to play either first or third base.

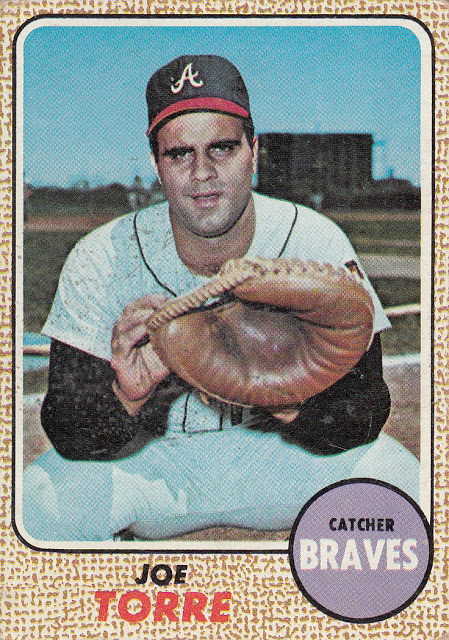

That was soon to change. Frank told Joe that if he were to switch to catching, he would get noticed. The following summer he caught with the Cadets and was signed by scout Honey Russell of the Milwaukee Braves on August 24, 1959 for a bonus of $22,500.8

Frank had the most significant impact on Joe’s development. “Frank was the kick in the butt I needed to amount to anything in life. It was Frank who toughened me up, Frank who turned me into a catcher, Frank who put me through high school, Frank who used to send me spending money, even when he was off fighting in Korea, and Frank who was everything I ever wanted to be. He was a ballplayer. I may not have had a father in my life then, but I sure as hell had a hero.”9

Joe was still conscious of his weight. On the eve of his signing with the Braves, Joe was seen dressed in a t-shirt and white shorts jogging in Brooklyn. He was sweating profusely, trying to sweat off a few pounds to be in the best shape possible to start his professional career.10

After dropping about 20 pounds and batting .364 in the Florida Instructional League in the fall of 1959, he was assigned to Eau Claire in the Class C Northern League in 1960, where he played for a former catcher, Bill Steinecke. As Eau Claire is 250 miles from Milwaukee, the Braves were able to follow his progress as he batted a league-leading .344 with 16 homers and 74 RBIs, and was named his league’s Rookie of the Year, earning a late season call-up.11

On September 25, 1960, little over a year after first signing with the Braves, he made his major- league debut. In the bottom of the eighth, he pinch-hit for Warren Spahn, and ignited a rally with a single to center field off a Harvey Haddix fastball. He was promptly removed for a pinch runner. The Braves scored a pair of runs to tie the game at 2-2, and went on to win 4-2 courtesy of an Eddie Mathews two-run-homer in the tenth inning. At the game was Joe’s manager from his days with the Brooklyn Cadets, Jim McElroy.12

In the fall of 1960, Joe used part of his bonus money to buy a 1960 Ford Thunderbird. Frank knew an auto dealer in Milwaukee and the dealer’s young son handled the transaction. The dealer’s son was a bit of a baseball fan. Later on, that auto dealer’s son, Bud Selig, would become more involved in baseball as he ascended to the office of Commissioner of Baseball.

Over the years, Torre’s catching ability met with mixed reviews. In 1962 and 1963 with the Braves, Del Crandall was still around and Crandall was the “personal catcher” for Braves ace Warren Spahn. Although Torre won a Gold Glove in 1965, Bill James noted that there were other catchers more deserving of the honor.13 Whitey Herzog, never at a loss for words, was high on Joe’s managerial abilities, but noted that “Joe Torre was the worst catcher I ever saw. The fans in the center field bleachers knew his number better than the ones behind home plate did!”14

During spring training in 1961, he got to play alongside his brother Frank for the first and only time as a professional. Frank was playing with Louisville when Joe was with the Braves in 1960. Joe started off the 1961 season with Louisville in the Class AAA American Association and was batting .342 with 24 RBIs in 27 games when the Braves brought him up to stay. Frank spent the entire 1961 season with Vancouver in the Pacific Coast League.

It was May 19, 1961 when Torre was summoned to his Louisville manager’s office. Crandall was injured with a sore throwing arm and Joe was to join the Braves on the road in Cincinnati. Joe’s minor-league days were over. He played both games of a doubleheader on May 21 and more than justified the call-up. In the first game, he led off the ninth inning with the Braves down 6-3 and slammed a Joey Jay pitch out of the park for his first major-league home run. The Braves went on to tie the score at 6-6, but lost the game 7-6 when the Reds pushed across a run in the bottom of the ninth. The Braves came back to win the nightcap, 3-2; Joe went 2-for-4 with a double.

During the course of the doubleheader, Torre was tested by the Reds. In the first game, he gunned down Eddie Kasko and pinch-runner Elio Chacon on steal attempts and in the second game he threw out Vada Pinson trying to steal third base in the third inning. He saved the best for last. With one out in the bottom of the ninth, Pinson was on third and Frank Robinson was on first. Braves pitcher Claude Raymond threw to first, and Pinson made a mad dash to home plate. Torre, blocked the plate, took the throw from first baseman Joe Adcock, and tagged out Pinson in a collision at the plate.15 Raymond secured the last out and the Braves win.

For the season, Torre batted .278 with 10 homers and 42 RBIs. He finished second in the Rookie of the Year balloting to Billy Williams of the Cubs.

In 1962, Crandall returned and Torre saw less action, getting into only 80 games, batting .282 with five homers and 26 RBIs.

In 1963, Torre won the starting job and started 94 games behind the plate for the Braves. Crandall started 67 games as catcher along with seven games at first base, and in those contests when Crandall caught, Torre played first and made a positive impression on manager Bobby Bragan. Bragan noted, “He’s got good hands, and he goes to his right very well. I’ve never seen a young right-handed first baseman make that tough first-to-second-to first double play as well.”16 He played in 142 games overall. He was selected as a catcher for the NL All-Star team, but was not a starter. Indeed, he did not get to play in the game. For the season, he batted .293 with 14 homers and 71 RBIs. One of those homers, against the Giants’ Juan Marichal on August 22, 1963 was his first career grand slam. Unfortunately for the Braves, it was too little too late as the Giants won 8-6.

Crandall was traded to the Giants prior to the 1964 season and Torre responded with his best season to date, batting .321 with 20 homers and 109 RBIs. He again was selected to the All-Star team, this time as a starter.

In 1965, he earned the Gold Glove and was once again solid with the bat, slugging 27 homers to go along with 80 RBIs and a .291 batting average. In that year’s All-Star Game, he once again started and this time caught the entire game. His first inning two-run home run put the National League out in front, 3-0, and they won the game, 6-5.

In 1966 the Braves moved to Atlanta and the team used Atlanta Stadium as a launching pad, hitting 207 homers. Joe did not miss out on the party. He began the party by hitting the first major-league homer in Atlanta on April 12 against Bob Veale of the Pirates. That game featured two Torre solo home runs, but they were not enough to offset three Pirates runs and the Braves lost 3-2 in 13 innings. Over the course of the season, he had five games in which he had two homers. His career-high 36 dingers were second on the team only to Hank Aaron’s 44, and went along with a .315 batting average and 101 RBIs. Once again, he was the starter in the 1966 All-Star Game and, for the first three innings, received pitches from fellow Brooklyn sandlotter Sandy Koufax. Sandy stayed in Torre’s life and in 1999, when Torre was diagnosed with prostate cancer, Koufax made a special trip to the Yankees’ spring training base to check on his old friend.17

In 1966 the Braves moved to Atlanta and the team used Atlanta Stadium as a launching pad, hitting 207 homers. Joe did not miss out on the party. He began the party by hitting the first major-league homer in Atlanta on April 12 against Bob Veale of the Pirates. That game featured two Torre solo home runs, but they were not enough to offset three Pirates runs and the Braves lost 3-2 in 13 innings. Over the course of the season, he had five games in which he had two homers. His career-high 36 dingers were second on the team only to Hank Aaron’s 44, and went along with a .315 batting average and 101 RBIs. Once again, he was the starter in the 1966 All-Star Game and, for the first three innings, received pitches from fellow Brooklyn sandlotter Sandy Koufax. Sandy stayed in Torre’s life and in 1999, when Torre was diagnosed with prostate cancer, Koufax made a special trip to the Yankees’ spring training base to check on his old friend.17

In early-June 1967, the Braves re-acquired Bob Uecker from the Phillies. Joe and Bob were old friends, having played together at Louisville in 1961, and Joe was happy to see Uecker join the Braves. Uecker was able to handle the knuckleball offerings of Phil Niekro and Joe and Bob, who roomed together, had great times off the field enjoying the Atlanta nightlife.

On the field, the 1967 season was a case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde for Joe Torre. After a slow start, his bat heated up and he was batting .302 on August 20 with 17 homers. However, he went into a slump at that point, batting only .213 with three homers in his last 40 games. For the season, he batted .277 with 20 homers and 68 RBIs.

Torre’s numbers fell off over even further in 1968 as he batted only .271. His power numbers were off significantly, and he had only 10 homers and 55 RBIs. The drop in his productivity in 1968 was heightened when he took a pitch from Chicago reliever Chuck Hartenstein off the cheek on April 18, causing hairline fractures of the left cheekbone and the roof of his mouth, and missed 27 games. Of even greater concern, his ability to throw out baserunners dropped to 26%, far less than the 48.6% and 46.7% figures of the prior two years. Also, during the 1968 season, Torre was arrested for driving under the influence of alcohol.

Torre served as player representative in his days with the Braves and strongly supported the hiring of Marvin Miller as executive director of the player’s union in 1966. In 1968, Joe fought hard for the collective bargaining agreement with the owners and this did not sit well with the Braves’ ownership.

After the season, the Braves offered him the maximum pay cut allowable under the current agreement and it was clear that Torre’s days in Atlanta were numbered. Atlanta offered to trade Torre, only 28 at the time, to the Washington Senators for first baseman Mike Epstein and catcher Paul Casanova, but Washington owner Bob Short said no. He was also brokered to the Mets in a deal that fell through. Eventually, Atlanta dealt Torre to St. Louis for first baseman Orlando Cepeda during spring training on March 17, 1969.

In 1969 with St. Louis, starting 142 games at first base and only 16 behind the plate, Torre batted .289 with 18 homers and 101 RBIs. He set a then personal high with six triples. However, the Cardinals, who had won the previous two National League pennants, slipped to fourth place in the inaugural six-team Eastern Division, while Joe’s old team, the Braves, won in the West. But Joe, during that season, gained a friend for life in pitcher Bob Gibson.

He also, by his own admission, grew as a person during that first year in St. Louis. From strategizing with catcher Tim McCarver and Coach George Kissell to being surrounded by a professional group of players managed by a low key Red Schoendienst, Joe was ready to embark on his most successful seasons.

The following season, he saw more action behind the plate, as on October 7, 1969 in an historic blockbuster seven-player trade, the Cardinals sent McCarver, center fielder Curt Flood, and two other players to the Philadelphia Phillies for slugging infielder Dick “Richie” Allen and two other Phillies players. Allen was to play first base with Torre going behind the plate. But the trade had other ramifications.

There were many “moments in time” in Joe Torre’s life, and one of those moments came on December 13-14, 1969 in San Juan, Puerto Rico. In a year known more for a small step on a spheroid visible in the night’s sky and a miracle not far from Joe’s boyhood home in Brooklyn, Joe Torre, the Cardinals’ player representative, met with his fellow player representatives at the Players Association Winter Meeting. At 10:00 AM on December 13, Marvin Miller gaveled the meeting to order. Torre’s 1969 teammate, Curt Flood, was in attendance. He was unhappy with being traded to Philadelphia and elected to contest the trade and baseball’s reserve clause.

Torre and the other 24 representatives in attendance elected to throw their support behind Flood. As David Maraniss noted, “How could Cardinals player representative Joe Torre, in the prime of his playing days, imagine that three-and-a-half decades later he would be managing a $220 million payroll of mercenary Yankees, many of whom made more in a year than he would earn his entire career?”18

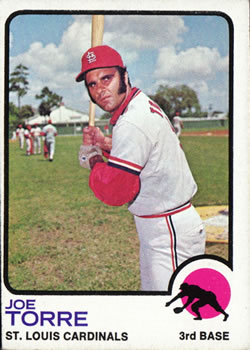

In 1970, Torre split his time between third base and catching, starting 88 games behind the plate and 72 at third base for the Cardinals. His numbers were a vast improvement over the preceding years. His career-high batting average of .325 placed him second in the league to former Atlanta teammate Rico Carty, and his 203 hits were also a career best. His 21 homers were his best since 1966, and his 101 RBIs marked his second consecutive season at or above the 100 RBI plateau.

The following season, the Cardinals made some changes. Torre was moved to third base full-time after Mike Shannon contracted nephritis, which ended his playing career. Ted Simmons became their full-time catcher. The Cardinals wound up with less than they expected, so to speak. During the offseason, Torre committed himself to shedding pounds, went on the Stillman diet, and came to spring training in the best shape of his life. He shed 20 pounds to get down to 208 and, during the season, got as low as 195.19

Anchored at third base in 1971, Joe Torre had the best season of his career. He led the league in batting (.363), hits (230), and RBIs (137), slammed 24 homers, and was selected the National League MVP. He once again was on the All-Star team, this time as the starting third baseman. Although the Cardinals won 90 games, more than any team Torre ever played on, they finished second to the Pirates, and once again Joe would not make it to the World Series. The story of the season, as much as his on-field statistics, was his success at losing weight. Joe noted, “I must have been the only MVP in history who received more requests for a diet program than for an autograph.”20

Anchored at third base in 1971, Joe Torre had the best season of his career. He led the league in batting (.363), hits (230), and RBIs (137), slammed 24 homers, and was selected the National League MVP. He once again was on the All-Star team, this time as the starting third baseman. Although the Cardinals won 90 games, more than any team Torre ever played on, they finished second to the Pirates, and once again Joe would not make it to the World Series. The story of the season, as much as his on-field statistics, was his success at losing weight. Joe noted, “I must have been the only MVP in history who received more requests for a diet program than for an autograph.”20

He was with the Cardinals for three more seasons, but his numbers never approached those from 1971. He had two more All-Star appearances in 1972 and 1973, but his numbers were on the decline. From 1972 through 1974, he batted .286 with an average of 12 homers and 73 RBIs per season. Off-the-field events also impacted Torre during this time. His marriage was not going well and his mother passed away in May 1974. He played mostly at first base during his final two seasons with the Cardinals, but, by the end of the 1974 season, the Cardinals were looking for more productivity.

One last trade occurred during Torre’s playing career. On October 13, 1974, he was traded to the New York Mets for pitchers Tommy Moore and Ray Sadecki. Torre was 34 when he joined the Mets for the 1975 season. The Mets had won the World Series in 1969 and National League pennant in 1973, but had dropped to fifth place and a 71-91 record in 1974. It was hoped that Joe would help make the team more competitive. In Torre’s first two years with the Mets, the team finished in third place. In 1975, he was reduced to part-time status, playing in 114 games and his numbers (.247-6-35) were not nearly as good as his numbers had been with the Cardinals. Joe got an extra dose of humiliation on July 21, 1975 when he grounded into four double plays in a game against Houston, setting the National League record and tying the major-league record for most double plays grounded into in a single game.

The following season, his batting average jumped to .306, but his power numbers were still low (5 homers, 31 RBIs). The Mets, in 1976, were managed to an 86-76 record by Joe Frazier, who had won four championships while managing in the Mets’ minor-league system. He returned for the 1977 season, a year when the Mets had their worst record since 1967. Forty-five games into the season, Joe Torre, with no experience as a coach or manager at any level of organized baseball, replaced Frazier as manager.

Torre’s managerial debut with the Mets was on May 31, 1977 and the Mets defeated Montreal at Shea Stadium, 6-2. For a brief period of time, Joe was a playing manager, but he only had two plate appearances as a manager and played for the last time on June 17, 1977. Torre’s years managing the Mets were disappointing. The team traded away its franchise player, three-time Cy Young Award winner Tom Seaver, shortly after Joe took over as manager, and the team went 286-420 with him at the helm.

By 1981, the Mets were on their way to their fifth consecutive losing season, the team was in the midst of being sold, and Joe’s marriage was on the rocks. In the midst of all of this, there was a strike that caused a stoppage in play from June 12 through August 9. Joe’s personal life was a mess. He had married for the first time on October 21, 1963 but, from the outset, there were problems. His wife, Jackie, had been a Playboy bunny. They had one child, Michael, who was born in 1964, and were divorced shortly thereafter.21 Joe’s second marriage was to Diane “Dani” Romaine, who he had met at a ballgame in New York while playing with Atlanta in 1967. They married on January 13, 1968. Dani brought along a daughter Lauren from a previous marriage, and Joe and Dani had another daughter Tina in 1969. Although they stayed together for 13 years, it was an unhappy time for Joe and Dani. In 1981, they separated, and they were divorced just prior to the 1982 season.22

In late August, the Mets were in Cincinnati to play the Reds. August 23, 1981 was without a doubt the best of days for Joe Torre in a very long time. The Mets defeated the Reds 3-2 in ten innings as Joe made six strategic moves that all worked in the Mets favor, including a last inning defensive switch that led to a game-saving catch by left-fielder Bob Bailor. The win took the Mets record for the second half to 8-5 and put them in a virtual tie for the league lead with the Cardinals.23 That evening Joe and several of his coaches were sitting at the bar in Stouffer’s Hotel nursing drinks. Things were slow that night and Joe saw a young waitress reading a book. Bob Gibson invited her to join them and that is how Joe met Alice Wolterman. Six years later, to the day, Joe and Ali were married.24

Unfortunately, the 1981 season did not have a storybook ending for the Mets. Their second half record was 24-28 and the record for the overall season was 41-62. The Mets fired Torre at the end of the season. After being fired by the Mets, he was asked if he would consider managing again. “Yes, I plan to keep doing it until I get it right.”25 He began to get it right in 1982, and would ultimately get it very right in 1996.

In 1982, he returned to Atlanta to manage the Braves and, in his first season, made it to the playoffs, as the Braves won their first Western Division title since 1969. The ace of the pitching staff that season was 43-year-old Phil Niekro who went 17-4, and offensive power was provided by league MVP Dale Murphy. The team got off to a great start, winning its first 13 games of the season, and was leading the division by seven games on August 2. Then, the team went into a swoon, losing 15 out of 16 games and dropping to second place. Down the stretch, they won seven of 10 to win the division by one game over the Dodgers.

Second baseman Glenn Hubbard credited Torre for keeping his calm during the team’s August slump, stating “Even during our losing streak, he could have come out and blasted us, but he didn’t. Nobody was breaking any bats or helmets. He just helped keep us confident, and we came back.”26 In the then best-of-five National League Championship Series, they were swept by the Cardinals in three games. The following two years with the Braves, his teams finished in second and third, but the team won only 80 games in 1984 and Torre was dismissed at the end of the season. During the next five seasons, Torre did television commentary for the California Angels.

He returned to the dugout with the Cardinals as their field manager after 104 games in the 1990 season, three weeks after the sudden resignation of St. Louis manager Whitey Herzog. Torre had winning records in St. Louis from 1991-93, averaging just under 85 wins and a .523 winning percentage, but did not come close to getting the Redbirds to the postseason. Towards the end of the 1994 season, the players went on strike, and this had a deep impact on Joe, who had been a strong union man during his playing days. He was especially disturbed by the prospect of using replacement players in 1995, a situation that never materialized. The players came back in April, 1995 but the Cardinals got off to a bad start. They were 20-27 when Torre was fired in mid-June.

He had managed each of the teams for which he had played, and his combined record was a none-too-flattering 894-1,003. His prospects for another managing job were not good, and it appeared that his managing days, along with his World Series prospects, were over.

But a small glimmer of hope was on the horizon. Although there were three candidates ahead of him for the position that would ultimately take him at long last to the World Series and the Hall of Fame, on November 2, 1995, George Steinbrenner introduced Torre as the new manager of the New York Yankees. The media, thinking that Torre had no idea of what he was getting into, called him “Clueless Joe.” The media reception was at best lukewarm. He was replacing Buck Showalter, the AL Manager of the Year in 1994, who was not only popular but had led the team to a 237-182 record over the prior three seasons and their first trip to the postseason since 1981. In 1995, New York was the American League’s first wild-card team during the new division-round of the postseason playoffs. The Yankees won the first two games against Seattle only to be swept in the next three by the Mariners. The temperamental Steinbrenner, who had not extended Showalter’s contract beyond the 1995 season, was mad at the Yankees not going further in the playoffs. Steinbrenner, after the loss in the Division Series, offered a contract extension, but forced Showalter’s resignation by telling him that he would have to dismiss his hitting coach.27

Just after being selected to manage the Yankees, Joe and his wife Ali went to a four-day seminar on self-improvement in Cincinnati that proved invaluable to Torre during his years managing the Yankees. During those sessions, he became less guarded, shared his emotions, and became a better person for doing so. As Torre noted, “That weekend in Cincinnati taught me how to relax myself by putting everything into its proper category rather than thinking I could just take on all my problems at once, which is how you get overwhelmed.”28

In his first year with New York, Torre teamed with bench coach Don Zimmer to lead the Yanks to their first World Series win in 18 years. One of Torre’s major goals had been to remove tension from the clubhouse. “Pressure is part of the game, but you shouldn’t have tension.”29 This was not one of the power-laden Yankee teams of years gone by. Although the team hit 162 homers, not a single player had 30 or more. So the Yankees became more of a running team, manufacturing runs, stealing bases, and getting runs one at a time—at times to overcome large deficits. The team was so balanced on offense that nobody stood out and not a single Yankee finished in the top ten for MVP. Five players had ten or more stolen bases. The youngest player on the team, Derek Jeter, played in the most games. The 22-year-old shortstop won Rookie of the Year honors.

As far as the pitching was concerned, Andy Pettitte had a great season, going 21-8 and finishing second in the Cy Young balloting. He was their only pitcher to throw more than 200 innings and Torre was forced to rely on his bullpen. Early in the season, Torre had such little confidence in one of his relievers that he told the Yankees hierarchy to entertain offers. Then, the fastball of a young Panamanian came around and Mariano Rivera became the ultimate set-up man for John Wetteland’s 43 saves. The Yankees had peaks and valleys during the season, and won the Eastern Division by four games over Baltimore. They then went on to defeat Texas in the ALDS and Baltimore in the ALCS to win the American League pennant, and it was on to the World Series against Joe’s former team, the Atlanta Braves.

The Yanks lost the first game of the series, 12-1, but Torre was not concerned. Owner George Steinbrenner, on the other hand, was quite agitated. Torre told his boss not to worry. Joe said, “But then (after Game Two, win or lose) we’re going to Atlanta. Atlanta’s my town. We’ll take three games there and win it back here on Sunday.”30 And so, except for the quoted day of the week, it almost happened as Joe predicted. The key game was Game Four in Atlanta. At one point the Yankees were down 6-0, but they came back, tying the game in the eighth inning on a three-run homer by Jim Leyritz and winning the game 8-6 in ten innings. After the dramatic1-0 win in Game Five in Atlanta that gave the Yankees a 3-2 lead in the series, there was an unexpected and most appreciated stroke of good fortune. On the eve of the sixth game of the Series, Joe’s brother Frank underwent a successful heart transplant.31 Within hours, the dream was complete when the Yankees defeated the Braves, 3-2, on Saturday, October 26, 1996.

When the World Series victory was complete, Torre, at Don Zimmer’s suggestion, assembled the players for a victory lap around the field. As pitcher David Cone remembered, “It seems like we just floated around the field. Joe Torre sort of led us. Guys were just floating around the field. Next thing you know, the (police) horses were going nuts and the fans were reacting wildly. It was almost in slow motion. It was surreal.”32

He was named Sportsman of the Year by The Sporting News and American League Manager of the Year along with Johnny Oates of the Texas Rangers. As Steve Martinez wrote, “With heart, faith, and a calm confidence, our Sportsman of the Year led the Yankees to an improbable world championship and, in the process, turned a hard boiled city on its head and into a legion of Torre Adorers.”33

Zimmer and Torre formed a close bond which led Joe into a new area of interest. During that first season, on a road trip to Baltimore, Zimmer spent an afternoon at Pimlico race track and Joe gave him $400 to bet. Zimmer picked a few winners, making Torre all the richer. Joe was hooked on horse racing and came to own several horses, one of which ran in the Kentucky Derby in 2010. His baseball duties with the Dodgers that season gave him little opportunity to see the Derby-bound horse, Homeboykris, but he did take a side trip to Louisville when the Dodgers were in Cincinnati. The horse didn’t win the Derby, but Joe had “really enjoyed getting down there and watching the horse work and walking around the barn area.”34

A second World Series Championship win came in 1998, and this time the Yankees roared to the AL East championship with a then American League record 114 wins and defeated Texas in the ALDS and Cleveland in the ALCS. They swept the San Diego Padres in the World Series to finish things off. Torre won his second American League Manager of the Year Award in three years. Although his players were “pretty good,” Torre forged a rapport that was recognized by everyone. For Joe, “selling the team concept was very, very easy. It’s incredible how (the players) were able to stay sharp on a daily basis.”35

During those years with the Yankees, Zimmer and the other coaches would learn firsthand that there were three off-the-field things (aside from family) that were of utmost important to Joe Torre – the best cigars, the best wines, and the best restaurants.36

Success was sweet, but in 1999, adversity entered Torre’s life when he was diagnosed during spring training with prostate cancer. The disease was caught in time, and Torre made a complete recovery. George Steinbrenner noted, “It’s been a very tough week for the Yankees (Joe DiMaggio had just died, Catfish Hunter had been ravaged by Lou Gehrig’s disease) but we’ll be able to handle it.”37 Bench coach Zimmer took over as interim manager until Torre returned after the team had played 36 regular season games. The team was winning despite much in the way of bad news. Death took former Yankee pitcher Catfish Hunter and three players—Scott Brosius, Luis Sojo, and Paul O’Neill—lost their fathers. O’Neill’s father died just before the fourth game of the World Series. Paul played the game, on the verge of tears, as the Yankees won their second consecutive World Series Championship (another four game sweep – this time against the Braves).38

They would make it three straight championships when they defeated the New York Mets in five games in 2000.

Torre was a believer in having his players prepared. In spring training 2001, he made sure that his shortstop knew how to position himself to back up a cut-off throw. So it was, that in the 2001 ALDS, with New York down two games to none, during the seventh inning of what could be an elimination contest against Oakland, Derek Jeter was in position to field a wildly off-line throw from right field and flip the ball backhanded to catcher Jorge Posada to nail Jeremy Giambi at home by the narrowest of margins and keep the Yankees on the path to their fourth straight World Series.39 The Yankees then defeated the Seattle Mariners four games to one in the ALCS. Although they lost to the Arizona Diamondbacks in seven games, the Yankees had realized Joe Torre’s dream of going to the World Series, not once, but five times in six years.

After the 2003 season ended with a World Series loss to the Florida Marlins, Zimmer, who had been on the receiving end of much Steinbrenner criticism, elected to move on. Torre was disturbed that a man with whom he had grown to be friends had been singled out for criticism by Steinbrenner. As Torre stated, “It bothers me because we’ve been together. I learned a lot from Don Zimmer. That is something that is not going to leave me.”40

During the 2004 season, the Yankees-Red Sox rivalry reached its greatest heights. Each series was like a war with the greatest of highlights and the most devastating of disappointments. On July 1, the Red Sox were at Yankee Stadium and the teams played for 13 innings. After four hours and twenty minutes, the Yanks had a 5-4 win highlighted by Derek Jeter’s dive into the stands to corral a pop fly in the 12th inning, stranding two runners on base. The Yankees used 20 players and the Red Sox 17, as the Yankees swept the three-game series and took an 8½ game lead in the standings. The Red Sox mounted a late-season charge and pulled to within two games of the lead, but the Yankees held on to win the division by three games. In the ALCS, the Yankees and Red Sox met again. The Yankees were up three games to none and three outs away from another trip to the World Series when Boston made an unprecedented comeback and swept the last four games of the championship series and moved on to beat St. Louis for their first World Series win since 1918.

In each of Torre’s last three years with the Yankees, the team lost in the first round of the postseason competition, He suspected during the 2007 campaign, that he would be leaving the Yankees, and began clearing things out of his office midway through the season. He noted, “Walking into that room in Tampa (after the season, on the day of his last meeting with the Yankees’ brass), was one of the toughest things I ever did in my life. After five minutes, I knew it was over.”41 Yankee management elected to offer Torre a salary cut from $7.5 million to $5.0 million, which he refused.

After the 2007 season, Torre moved on to manage the Los Angeles Dodgers for three seasons. In 2008 and 2009, his teams advanced to the playoffs, making it 14 consecutive visits to the postseason for Torre.

Although the circumstances of his leaving the Yankees were hurtful, Torre’s bond with the team is lasting, and it was fitting that he and Don Mattingly returned to Yankee Stadium for the unveiling of the memorial monument for George Steinbrenner in September, 2010. As Mattingly stated, “I really felt that Joe needed to go back (from Los Angeles). I really felt good about that. From deep down in my Yankees roots, it made me feel good that the Yankees had him back. It was a good feeling.”42 Joe offered that “George is responsible for the best years of my life, professionally. George, in my opinion, not only belongs in Monument Park. He belongs in the Hall of Fame.”43

Recognizing Joe’s work with the Safe at Home Foundation, President Obama appointed Torre, in 2010, to serve on the National Advisory Committee on Violence Against Women. Torre was honored at the Ellis Island Family Heritage Awards in 2011, not necessarily for his baseball achievements but more for his work with the Safe At Home Foundation. “Margaret’s Place”, a tribute to Torre’s mother, provides a place for adolescents to talk with each other and work through issues involving domestic violence.44

After leaving the Dodgers at the end of the 2010 season, Joe accepted a position in the Office of the Commissioner of Baseball as Executive Vice-President of Baseball Operations.

As so eloquently stated by David Halberstam, Torre is “a man secure in his knowledge of who he is and secure in his faith. Though he would prefer to win, rather than to lose, how he behaves as a man and how he sees himself is not based on his career winning percentage. The key to Torre is that he is a good baseball man, but he also knows there is much more to life than baseball, and that, finally, it is how you behave, more obviously when things are not going on well, that defines you.”45

Last revised: June 19, 2014

Sources

Books

Feinstein, John. One on One: Behind the Scenes with Greats in the Game (New York, Little Brown, and Company, 2011).

Golenbock, Peter. George: The Poor Little Rich Boy who Built the Yankee Empire (Hoboken, New Jersey, John Wiley and Sons, 2009).

Herzog, Whitey. You’re Missin’ a Great Game: From Casey to Ozzie, the Magic of Baseball and How to Get it Back (New York, Simon and Schuster, 1999).

James, Bill. The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract (New York, Free Press, 2001).

Leavy, Jane. Sandy Koufax: A Lefty’s Legacy (New York, HarperCollins, 2002).

Madden, Bill. Pride of October: What it was to be Young and a Yankee (New York, Warner Books, 2003).

Maraniss, David. Clemente: The Passion and Grace of Baseball’s Last Hero (New York, Simon and Schuster, 2006).

Mele, Andrew Paul. The Boys of Brooklyn: The Parade Grounds – Brooklyn’s Field of Dreams (Bloomington, Indiana, Author House, 2008) .

Ross, Alan. Yankees Century: Voices and Memories of the Pinstripe Past (Nashville, Tennessee, Cumberland House, 2001).

Shalin, Mike. Donnie Baseball (Chicago, Illinois, Triumph Books. 2011).

Shapiro, Milton J. Heroes Behind the Mask (New York, Simon and Schuster, 1968).

Stout, Glenn. Everything They Had: Sports Writing from David Halberstam (New York, Hyperion, 2008).

Torre, Joe (with Tom Verducci). Chasing the Dream: My Lifelong Journey to the World Series (New York, Bantam Books, 1997).

Verducci, Tom (with Joe Torre). The Yankee Years (New York, Doubleday, 2009).

Vincent, Fay. The Last Commissioner (New York, Simon and Schuster, 2002).

Zimmer, Don (with Bill Madden).The Zen of Zim (New York, St. Martin’s Press, 2004).

Newspaper and Magazines

Curry, Jack. “After Torre Pinches himself, the Yanks are Still Champions”, The New York Times, October 28, 1996.

Goetz, Bob. “Dugout to Derby: Torre’s Interest Grows”, The New York Times, April 26, 2010.

Halberstam, David. “Torre Makes a Good Boss”, ESPN.com, December 5, 2001 reprinted in Everything They Had: Sports Writing from David Halberstam, edited by Glenn Stout (New York, Hyperion, 2008).

O’Connor, Ian (New York Daily News). “Life has Changed Plenty for Ali Torre, Too”, reprinted in The Day (New London, Connecticut), February 16, 1997, e6.

New York Daily News

The New York Times

The New York Post

The Sporting News

Notes

1 Joe Torre, Chasing the Dream, 11.

2 Alan Ross, 18.

3 Torre, Chasing the Dream, 15, 18.

4 Peter Golenbock, 288.

5 Mark Newman, “Torre pays Tribute to mom at Ellis Island Awards”, MLB.com, April 23, 2011.

6 Torre, Chasing the Dream, 31.

7 Andrew Mele, 78

8 Torre, Chasing the Dream, 63.

9 Torre, Chasing the Dream, 36-37.

10 Mele, 175.

11 Milton Shapiro, 141.

12 Mele, 284.

13 Bill James, 375-376

14 Whitey Herzog, 141.

15 Torre, Chasing the Dream, 80.

16 Shapiro, 146.

17 Jane Leavy, 36

18 David Maraniss, 231-233.

19 Torre, Chasing the Dream, 115.

20 Torre, Chasing the Dream, 120.

21 Torre, Chasing the Dream, 93-95.

22 James Norman, ”Torre Dumps Wife as New Team Takes to the Field”, New York Post, April 10, 1982.

23 Parton Keese, “Torre’s moves work as Mets beat Reds 3-2, in 10”. The New York Times, April 24, 1981. C-6

24 Torre, Chasing the Dream, 135-136

25 Ira Berkow, “The Magic Finally Arrives for Joe Torre” The New York Times, April 21, 1982.

26 Miami Herald, August 30, 1982,

27 Marty Appel, 492.

28 Torre, Chasing the Dream, 30.

29 Torre, Chasing the Dream, 165.

30 Golenbock, 295.

31 Golenbock, 296.

32 Jack Curry, The New York Times, October 28, 1996.

33 Steve Martinez. “Sportsman of the Year”, The Sporting News, December 16, 1996, 42-44

34 Bob Goetz, The New York Times, April 26, 2010.

35 Red Beaton, USA Today, November 13, 1998.

36 Don Zimmer, 75.

37 “Torre Leaves Yanks to Treat Prostate Cancer”, Oneonta Star, March 11, 1999.

38 Bill Madden, 424-425.

39 Fay Vincent, 300.

40 The Sporting News. November 4, 2003.

41 John Feinstein, 284.

42 Mike Shalin, 167-168.

43 Mike Feinsand, “Honors for Owner End Three-Year impasse.” New York Daily News, September 21, 2010.

44 Mark Newman, “Torre pays Tribute to Mom at Ellis Island Awards”, MLB.com, April 23, 2011.

45 Glenn Stout, 139-140.

Full Name

Joseph Paul Torre

Born

July 18, 1940 at Brooklyn, NY (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.