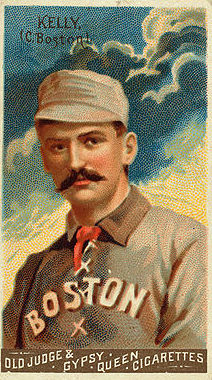

King Kelly

Mike “King” Kelly was professional baseball’s first matinee idol: the first ballplayer to “author” an autobiography, the first to have a hit song written about him, and the first to have a successful acting career outside the game. A handsome man with a full mustache and a head of red hair, Kelly through his fame helped change professional baseball from a pleasant diversion into America’s most popular sport. At his peak Kelly earned the highest salary in the game. He spent every cent he made, and died almost penniless less than a year after he played his last professional game.

Mike “King” Kelly was professional baseball’s first matinee idol: the first ballplayer to “author” an autobiography, the first to have a hit song written about him, and the first to have a successful acting career outside the game. A handsome man with a full mustache and a head of red hair, Kelly through his fame helped change professional baseball from a pleasant diversion into America’s most popular sport. At his peak Kelly earned the highest salary in the game. He spent every cent he made, and died almost penniless less than a year after he played his last professional game.

Michael Joseph Kelly was born on New Year’s Eve, 1857, in Troy, New York, to Irish immigrants Mike and Catherine Kelly. Mike and Catherine had left Ireland during the 1840s to escape the potato famine. After landing in New York City, they moved 125 miles up the Hudson to Troy, at that time a bustling commercial town at the eastern terminus of the Erie Canal.

The United States in 1857 had 31 states and approximately 31 million people. Mike Kelly was born three years before Abraham Lincoln’s election and the start of the Civil War. Baseball was largely an amateur sport in those days. Different forms of the game competed with one another and with cricket for players and fans.

In 1862, when Mike was 4 years old, his father joined the Union army and marched south with Troy’s volunteer regiment, leaving Catherine to raise Mike and his older brother, James. Mike’s father re-enlisted after the Civil War and the family moved to Washington, DC. Kelly told the story of what happened next in his autobiography, Play Ball, Stories of the Ball Field: “Ill health compelled my father to leave the army, and we moved to Paterson, N.J. My father’s health didn’t continue to improve any, and we had not been in Paterson very long before he passed over to the great silent majority. My mother followed him not long after.”1

It’s an indication of Kelly’s character that, despite being orphaned at a young age, he stayed positive. The next passage states, “My boyhood days in Paterson were just the same as is usually spent by boys. In my more youthful days, out-door sports occupied most of my time after school-hours.”

Mike found work at a coal factory, where his job was to carry a bucket of coal from the basement to the roof. Once that was done for the day, he could leave and spend his time doing what he most enjoyed — playing baseball. One of his best friends in Paterson was Jim McCormick, who also became a professional player, winning 265 games in the major leagues. The two played sports, performed amateur theatricals, and enjoyed life as much as possible in the Paterson of the 1870s. For Mike, his friend Jim, and many other boys in Paterson, that meant days of hard manual labor for a few dollars, and as much “outdoor sport” as they could find.

Paterson was home to several amateur clubs. In 1873, when Mike was 15, he was recruited to play on Paterson’s top club, captained by Blondie Purcell, who later played on several teams in the National League. The Paterson club also included McCormick and Edward Sylvester Nolan, a pitcher so good he was known as “The Only” Nolan. By 1876 Kelly had become the starting catcher, with McCormick as pitcher. Their team, the Keystones, dominated local competition in the mid-1870s, but the haphazard nature of professional ball in the 1870s forced the best players to rely on luck to advance in their careers.

According to his autobiography, Kelly considered quitting baseball in 1877. He apprenticed himself to a weaver, but as he put it, “I was a crank [fan] on the game, and couldn’t leave it if I wanted to.”2 Kelly joined a team in Port Jervis, New York, and then was contacted by the Columbus (Ohio) Buckeyes, a minor-league team. In all probability McCormick was responsible for scouting Kelly. Kelly was happy to sign his first professional contract, although he said that the players didn’t always get the money they were promised. Kelly’s batting average for his first year as a pro was only .156.3 The Buckeyes lost money and disbanded on September 15.

The Buckeyes did play enough exhibition games against National League teams for those teams to evaluate talent, and the Cincinnati Red Stockings offered Mike a contract for 1878. Indeed, they thought enough of Kelly to make him one of their 10 reserved players. At the age of 20, Mike Kelly became a big-league ballplayer.

The Red Stockings signed Kelly as a catcher and an outfielder, but he played mostly in the outfield since the Red Stockings already had an established catcher, Deacon White. Mike played in 60 games, batted .283, and scored 29 runs. The Red Stockings, after having a losing record the previous year, finished over .500, only four games out of first place.

In 1879 Kelly became a star. He batted .348, third in the league. He was fourth in runs scored, third in hits, and third in triples. He also began to develop a reputation as a heady ballplayer, who took advantage of his superior “base ball brains.”4 In one game between Cincinnati and Cap Anson’s Chicago White Stockings, Kelly stroked a double to left. After he rounded second, the ball came in to Chicago second baseman Joe Quest, who thought he tagged Kelly out. The umpire called Kelly safe, which led to a fervent argument at second base between the umpire and most of the Chicago players. Kelly, realizing that no one had called time, jumped up and came home to score, thus calling himself to the attention of Cap Anson.

Kelly had a great 1879 season, but the Cincinnati club didn’t. The club reportedly lost $10,000, a significant sum for the time. Owner J. Wayne Neff simply released all of his players in September, saying he couldn’t pay them.5 This left Kelly free to seek other employment for the 1880 season, reserve clause or no.

After the 1879 season Kelly went on a California barnstorming trip with several other major leaguers, including Purcell and Anson. According to Kelly’s autobiography, this fall trip made the players “a pocketful of money.”6 The California fans loved Mike’s bantering on the field, his good-natured personality, and his “kicking” or baiting umpires. He performed so well that Anson asked him to join the Chicago club.

Kelly didn’t get so excited by the prospect that he forgot to bargain for the best salary. He held out until Anson agreed to meet his figure. At the age of 22 Kelly was about to become one of the biggest stars on the first great professional team of the 1880s, the Chicago White Stockings.

When Kelly reported to Chicago on April 1, 1880, he was astounded to find that Anson expected him to lose 20 of his 170 pounds. Anson’s hard training got Kelly and the rest of the team into shape for the season. It’s hard to say whether Kelly did lose 20 pounds that year, because his reported height and weight for most of his career was 5-feet-10 and 170 pounds. There’s no question that young Kelly and the other White Stockings did round into shape by the start of the 1880 season. The team got off to such a great start that soon all professional teams imitated the White Stockings’ “spring training.”

Chicago was the biggest city in the National League in 1880 and usually led in attendance. Owned by former player and entrepreneur Albert Spalding and captained on the field by the 28-year-old Anson, the White Stockings had the best management and financial resources, and assembled some of the best players available. In addition to Anson and Kelly, the team included Silver Flint, Ned Williamson, Abner Dalrymple, George Gore, Larry Corcoran, and Tom Burns. Flint was the team’s regular catcher, playing without a glove, mask, or any equipment. Kelly played mainly in the outfield, and was the team’s “change” catcher. Ever the innovator, Kelly adopted the use of the catcher’s glove, mask, and chest protector to help him stay in the game.

Anson, in his biography, A Ball Player’s Career, characterized Kelly in the 1880s as follows: “(Kelly) came to Chicago from Cincinnati, and soon became a general favorite. He was a whole-souled, genial fellow, with a host of friends, and but one enemy, that one being himself.”7

Anson wrote about how he tried to reform Kelly’s drinking habits and keep him in shape, but no matter how many times Kelly swore to give up booze and stay on the straight and narrow, he would always fall off the wagon. In the 1880s many ballplayers were notorious drunks, including Kelly’s teammates Williamson, Gore, and Flint.

The White Stockings opened the 1880 season in Cincinnati, Kelly’s former town, and Mike won the opener, 4-3, with a home run. It was to be his only home run of the season, but that was still 25 percent of the team’s total of four. The White Stockings didn’t need home runs to dominate that season. They finished with a 67-17 record, 15 games ahead of second-place Providence. Their .798 winning percentage remains a National League record. Part of that was due to on-field innovations devised by Kelly. He was an expert at the hit-and-run. He experimented with different methods of getting past infielders to the base. Kelly gets credit for inventing the hook slide, which in his era was called the Chicago slide.

In Slide, Kelly, Slide, a biography of Kelly, author Marty Appel quotes early baseball historian Maclean Kennedy about Kelly’s baseball prowess. Kennedy saw Kelly play, and wrote, “There was never a better or more brilliant player. Colorful beyond description, he was the light and the life of the game. … He was one of the quickest thinkers that ever took a signal. He originated more trick plays than all players put together. … As a drawing card, he was the greatest of his time. Fandom around the circuit always welcomed the Chicago team, with the great Anson and his lieutenant, King Kelly.”8

Kelly batted a respectable .291 in 1880. Gore, his teammate, won the batting title at .360, with Anson second at .337. Off the field Kelly became known as a fashion plate. He liked to frequent taverns and buy rounds for his friends. He loved the theater, attending both plays and vaudeville. It was to be a pattern throughout his brief life. Kelly made a great deal of money for his time, but spent every penny enjoying himself.

Anson kept the team intact for the 1881 season. Kelly again showed his ability to take advantage of situations by cutting, or deliberately running 15 to 20 feet inside third base during a game when the umpire’s attention was elsewhere, to score the winning run in a 5-4 game on May 20 against Boston.9 A writer at the game reported this, but it was certainly not the first or last time Kelly pulled that trick.

The 1881 pennant race was closer than 1880’s, but Chicago still won going away with a nine-game lead. Anson won the batting title with a .399 average. Kelly and his teammate Dalrymple tied for sixth in the league with a .323 average. Kelly finished second in runs scored with 84 in 82 games.

After the season Kelly returned to Paterson and married his girlfriend, Agnes Hedifen, on October 25, 1881. They often spent the offseason at her brother’s farmhouse in Hyde Park, New York.

In his autobiography Kelly called the 1882 White Stockings the greatest team he ever played on, and perhaps the greatest team of all time. They received their first strong challenge for the pennant from the Providence Grays, managed by Harry Wright. The race came down to a three-game series in Chicago in September. The White Stockings swept three close games from the Grays, and Kelly made the key play. As he slid into second as the first out of a sure double play, Kelly flung his hand up and pushed shortstop George Wright’s arm so that the sure out turned into a two-base error. Afterward manager Harry Wright blamed the losses on “Kelly’s infernal tricks.”10

Kelly had a subpar year in 1883, hitting .255, and the White Stockings finished second to the Boston Beaneaters. In 1884 overhand pitching was allowed and averages went down, but Kelly hit a league-leading .354 and scored 120 runs. The White Stockings finished tied for fourth to the Providence Grays and the amazing Hoss Radbourn, who won 59 games. Kelly spent most of his time in the outfield but also played all the infield positions, caught, and even pitched in two games. He continued to invent plays. Running at third base in a close game against Detroit, he faked an injury to give Williamson, who was on second, a reason to come over and check on him. Kelly alerted Williamson that he would dash for home on the next pitch and for Williamson to be ready to follow right behind him. Detroit, astounded at Kelly’s quick recovery, didn’t think to throw the ball until he was close to the plate with Williamson right behind. Detroit catcher Charlie Bennett got the ball and was about to tag Kelly when Kelly opened his legs wide and Williamson slid through them and around Bennett to score because Bennett wasn’t expecting it. Later, of course, the rules were changed so a runner would be called out if he passed the runner ahead of him.11

In 1885 the White Stockings were back on top. Owner Albert Spalding and Anson brought in Kelly’s old friend Jim McCormick to pitch alongside future Hall of Famer John Clarkson, and the club moved into a brand-new park, the West Side Grounds. The White Stockings got off to a great start, and it appeared that the only thing that could stop them was Chicago’s night life. Kelly wasn’t the only drinking man on the team, others being Gore, Williamson, Flint, and a new young substitute outfielder, Billy Sunday. By midsummer the New York franchise earned its nickname Giants with a lineup that included John Montgomery Ward, Roger Connor, Buck Ewing, and Mickey Welch. The pennant was still in doubt when the Giants came to Chicago in late September for four games. Anson’s men took three out of four. Kelly led all batters with seven hits in the four games, and scored five of Chicago’s 25 runs. For the season he batted .288 and led the National League for the second straight year with 124 runs scored.

After the season the White Stockings played a series against the American Association champion St. Louis Browns for what was billed as the US Championship. Unlike a modern World Series, Spalding and Browns owner Chris Von der Ahe negotiated a 12-game traveling exhibition series with a top prize of $1,000 for the winning team. One game was in Chicago, three in St. Louis, and the rest in a variety of National League cities. The series was marred by poor umpiring, a controversial tie game, a potential forfeit, and poor play on both sides. At the end of the series, Spalding and Von der Ahe decided to count the disputed second game a forfeit for Chicago, because that enabled them to claim the shortened series as a tie between the teams, making each team 3-3-1. Neither owner would then have to pay the $1,000 purse. Kelly had a good series at the plate, hitting over .300, but made five errors.12

In 1886 the 28-year-old Kelly was arguably the biggest star in a star-studded National League. Newspapers and fans routinely called him King Kelly or The Only Kelly, a cherished sobriquet because of the large number of Irish immigrants in the United States at the time. Kelly responded to the adulation with his best season. He led the league in batting with a .388 average, led in runs scored for the third straight year with 155, and had 32 doubles, 11 triples, and 53 stolen bases.

During the 1886 season Spalding made a strong effort to curtail the excessive drinking of some of his stars, including Kelly, McCormick, and Williamson. At one point Spalding held back $250 from their pay, which they could earn back by staying sober. During the summer he had detectives follow the players, and fined some $25 for excessive drinking. Kelly at the time was paid at least $2,000 per season by the White Stockings, and had income from other business activities. The fines were significant, but nothing could curb Kelly’s fondness for alcohol.

After a night of drunken revelry during the summer of 1886, Billy Sunday told his drinking buddies, “Goodbye. I’m going to Jesus Christ.”13 In his autobiography, Sunday wrote of how he was scared to tell his teammates he was reforming. The first man he saw at the park was Kelly, who said, “Bill, I’m proud of you. Religion is not my strong suit, but I’ll help you all I can.”14 That statement sums up his character — generous to a fault, willing to help everyone, but unable to tame his own demons.

The 1886 pennant race was a tight battle between the White Stockings and the Detroit Wolverines. The race came down to the end of September, when Chicago prevailed. Immediately after the season, Anson and Spalding took the team to Washington, where they met with President Grover Cleveland. Kelly counted that as one of the greatest achievements of his life.

Again Kelly played all over the field — mainly outfield and catcher, but also first base, second base, shortstop, and third base. Once again St. Louis won the American Association pennant. This time Spalding and Von der Ahe agreed to make the series a best-of-seven, with the first three games in Chicago, the next three in St. Louis, and the final game, if necessary, on neutral ground. The winner was supposed to take the entire gate for the series; the loser would get nothing. Chicago took two of the first three games. Kelly didn’t hit much, but made some heady plays at catcher, picking off the speedy Arlie Latham at second base on a dropped ball and tagging out Yank Robinson at home and holding on to the ball despite being spiked in the collision.

The series moved to St. Louis, but without starting pitcher Jim McCormick, who was said to have “rheumatism,” forcing Anson to pitch third baseman Williamson one game. The Browns won Games Four and Five easily, but found Chicago pitcher John Clarkson in fine form for Game Six. Chicago went ahead 3-1, but St. Louis tied it up. In the bottom of the 10th, Clarkson gave up a single to Browns center fielder Curt Welch. The next batter singled and Yank Robinson sacrificed. With the winning run just 90 feet away, Clarkson tried to quick-pitch the batter and lost control. The pitch went far over Kelly’s glove. Welch slid home with the winning run, in what came to be known as the $15,000 slide (even though some newspaper reports didn’t mention a slide at all), since the Browns received all the gate receipts.

After this devastating loss, Anson and Spalding decided to clean house and get some players who would be better able to keep in training. The Boston Beaneaters believed Kelly would attract the numerous Irish population of the city, and were willing to pay the amazing sum of $10,000 to purchase his contract. They paid Kelly $5,000 in salary, which was listed as the $2,000 National League maximum plus $3,000 for the use of his picture for advertising purposes.15

The record purchase price only increased Kelly’s celebrity. Young Boston fans began following him around town, asking him to sign his name on a piece of paper. Kelly may not have been the first baseball player fans followed for an autograph, but as the most famous he can certainly be given credit for popularizing the practice.

Kelly also received extra income from endorsements. A “Slide, Kelly, Slide” model sled was tried, as was a Kelly-branded shoe polish. Reproductions of a painting of Kelly sliding head-first into second base in front of a cheering crowd replaced paintings of Custer’s Last Stand and other scenes in Irish taverns throughout the city. In 1889 a song called “Slide, Kelly Slide,” written by John Kelly (no relation) for vaudeville star Maggie Cline, became a hit, selling millions of copies of sheet music. Later, in 1892, when early recording techniques allowed for songs to be reproduced, “Slide, Kelly Slide” became America’s first hit record.

Kelly justified the price of his sale from the start of the 1887 season. More than 10,000 fans packed the park for the Beaneaters’ first few home games, and the team got off to a fast start. Reports of Kelly’s high salary made people think he was rich, but as Kelly wrote at the time: “There are two classes of people whose wealth is always exaggerated by the great public. They are ball players and actors. There are a few rich ball players and a few rich actors, but they are few and far between. They find so many different ways of spending money, that it is very hard for them to save very much.”16

Kelly knew whereof he spoke. He liked to spend money at the faro table, the track, and, of course, the saloons, where he preferred whisky to beer. Still, Kelly liked to boast that he “will never be broke.”17 He had a good year in 1887, hitting .322, scoring 120 runs (although he didn’t lead the league) and stealing 84 bases. (That was the second year steals were an official statistic.) Boston finished fifth. The Boston Globe presented Kelly with a gold medal after the season inscribed to the “champion base stealer” of the Boston Base Ball Club.18 That medal is now in the Hall of Fame.

Kelly continued his tricky play. He was said to drop his catcher’s mask in front of home just as runners began to slide home to keep them from touching the plate. In the outfield he reportedly kept an extra ball in his pocket to use when a ball was hit over the fence to make it appear he had caught the ball. Perhaps the most repeated story was the time Kelly was on the bench in the bottom of the ninth with two outs. At the time the rules allowed a player to substitute himself into a game just by making an announcement. As the batter lofted a pop foul near the Boston bench, Kelly stood up and said in a loud, clear voice, “Kelly now catching.” He caught the ball barehanded and won the game. (This writer was unable to find a specific game associated with this story. It was constantly repeated, and whether or not it was true, it was an example of the sort of play Kelly was capable of.) As Chicago sportswriter Hugh Fullerton wrote, “He was perhaps the most brilliant individualist the game ever knew.”19

Kelly barnstormed through the West after the 1887 season, accompanied by his wife, Agnes. He made his first professional appearance on stage in Boston in a play called A Rag Baby. He received more than a minute of applause after he uttered his first line, and the play was a success. Kelly wrote, “Glad it was a success; glad that I lived through it.”20 He and a ghostwriter produced what was the first published autobiography of a ballplayer. Called Play Ball: Stories From the Ball Field, it was released in 1888, and sold for 25 cents.

Boston sent another $10,000 to Chicago in the offseason to purchase pitcher John Clarkson, and could boast in 1888 of its $20,000 battery, Kelly and Clarkson. However, this move did not bring the Beaneaters a pennant. The team jumped out to an early lead but faded, losing the pennant to the New York Giants. Kelly hit .318, third in the league, but his 85 runs scored and 56 stolen bases were both down from the previous season. As a catcher, he made 54 errors in 76 games and allowed 54 passed balls. In the winter of 1888 Spalding organized a world tour that pitted his Chicago team against a picked nine of the best players in the rest of the league. Spalding wanted Kelly, the biggest star in baseball, to join him. Kelly signed a contract to go on the trip, but backed out at the last minute, citing “business interests”21 in New York. Perhaps he just didn’t want to work again with Spalding and Anson; his reasons for skipping the trip were never made clear. He was back playing for Boston in 1889.

The Beaneaters fought bravely for the pennant until the last day of the 1889 season, finishing one game out. Kelly hit .294 and scored 120 runs in 125 games. His drinking may have made a significant difference for the team; he missed at least one crucial game down the stretch because he was too hung over to play.

After the 1889 season, simmering labor unrest between the owners and players broke into open warfare. The Players Brotherhood enlisted the help of some financial backers and formed the Players League, which attracted more than 100 players from both the National League and the American Association. The Players League had stars but not the financial acumen of the National League owners, who scheduled their games in direct competition with Players League games in their cities. Kelly was named captain and manager of the Boston Reds, the Players League franchise. As with everything else in his life, he exuded confidence. “I’m one of the bosses now,” he said. “Next year we will be in command and the former presidents will have to drive horse cars for a living.”22

But Kelly struggled with the business details of running a club. A sportswriter recalled seeing him wrestle with an account book. “This bookkeeping’s hell, me boy,” Mike told him.23 However, on the field the Boston Reds sparkled. In addition to Kelly, the team had Dan Brouthers, Radbourn, Tom Brown, Bill Daley, and Hardy Richardson.

In June the Reds went to Chicago for a four-game series. Spalding met with Kelly, who told him that the Players League clubs were all losing money and that launching it was a “foolish blunder.”24 Spalding laid a check for $10,000 on the table and told Kelly he could have that check and a three-year contract at a figure he could name if he rejoined the Beaneaters. According to Spalding’s memoirs, Kelly asked for a little time to think about it and went out for a walk. When he returned he said, “I’ve decided not to accept.”

Spalding said, “What? You don’t want the $10,000?”

Kelly said, “Aw, I want the $10,000 bad enough; but I’ve thought the matter all over, and I can’t go back on the boys. And, neither would you.”25

Spalding shook Kelly’s hand, and then Kelly borrowed $500 from Spalding.

The Players League lacked the deep pockets of the National League and folded after its one season. Kelly’s Boston Reds had the biggest attendance, and won the championship. Kelly hit .325 and stole 52 bases in what was his last all-around good year. As the players started looking for jobs for the 1891 season, Kelly found that neither Chicago nor Boston wanted him back. He ended up signing with Cincinnati’s American Association franchise for $1,750 to play and manage the team.26 No doubt the Cincinnati owners thought Kelly would draw a crowd. They named the team Kelly’s Killers.

The Cincinnati team couldn’t afford good players, and Kelly had to play any warm body. Attendance was poor, and after only five months in Cincinnati the franchise disbanded. Kelly moved to the Boston American Association franchise. After only eight days on that team Kelly accepted a better offer from the Beaneaters of the National League. This signing provoked another war between the American Association and the National League. Kelly didn’t play much for the Beaneaters, but after his arrival they reeled off 18 straight wins and won the National League pennant, Kelly’s seventh championship. After the season, Kelly and his wife joined the team on a European barnstorming tour.

The American Association dissolved after the 1891 season, with the National League absorbing four of the franchises. The 12-team league created a split season so that the first-half and second-half winners could have a championship series. Kelly was 34 during the 1892 season, and his skills were fading. He was never much for training, and was losing his speed and strength. He hit only .189 in 78 games, mostly at catcher. Boston won the first half and the Cleveland Spiders won the second half. The Beaneaters won the championship series, but without playing Kelly.

Kelly may not have expected to play baseball in 1893. He worked the vaudeville circuit during the offseason, talking about baseball and sometimes reciting that new poem “Casey at the Bat.” Monte Ward, the former leader of the Players Brotherhood, was engaged to manage and captain the New York Giants, and decided to bring Kelly to the team. As usual, the fans were happy to see him. But Kelly wasn’t in shape, and as a catcher had difficulty handling the swift pitches and puzzling curves of Amos Rusie. Ward ordered Kelly to dry out every morning in a Turkish bath to erase the effects of his nightly drinking, but it didn’t seem to improve his skills.27 The team’s fourth-string catcher, he played in only 20 games and hit .269. The 35-year-old Kelly played in his last major-league game on September 2, when Ward sent him in as a substitute in the fourth inning of a game the Giants led 15-3. Kelly hit a single and scored a run, leaving him with a lifetime average of .307, 1,813 hits, and 1,357 runs scored. The Giants finished fifth. After the season Kelly and Agnes had a child. We don’t know if it was a boy or a girl, but we do know that the baby was the reason Agnes stayed behind in Paterson when Kelly took ship for Boston in the winter of 1893-94 for a vaudeville engagement.

Kelly spent the winter booking vaudeville appearances, then signed on with an old friend, Albert Johnson, as captain and manager of the Allentown team in the Pennsylvania State League. Kelly smacked the league’s pitchers for a .310 average. But the Allentown franchise dissolved on August 6. Johnson sent Kelly and some of the players to a team he owned in Yonkers, New York. There Kelly finished his professional baseball career, hitting .377 in 15 games. Perhaps for the first time in his life, Kelly received some derogatory press. Reporters wrote that he was old and out of shape. Yonkers reserved Kelly for the 1895 season, but he must have known that his career was winding down. He prepared for that by taking some offseason work with Mike Murphy’s vaudeville act, appearing in a piece called “O’Dowd’s Neighbors.” They played a week at the Bijou Theater in Paterson before heading to Boston to play the Palace Theater, no doubt hoping to cash in on Kelly’s continuing popularity. Kelly had spent every cent he earned in baseball, and if he was going to support his wife, his baby, and his fancy lifestyle, he would have to make big money in theater.

Kelly left New York City on Sunday, November 4, 1894, and traveled by boat to Boston. A snowstorm hit during the journey, and Kelly took ill. Some reports have Kelly catching cold because he gave his overcoat to a freezing man on the boat. When he arrived in Boston he had chills and fever and rested at a friend’s house. Dr. George Galvin, former team doctor for the Beaneaters, saw Kelly at 2 in the afternoon, and found that he had difficulty breathing. By 4 P.M. on Monday, November 5, it was clear that pneumonia had set in, and Galvin moved Kelly to Emergency Hospital. It was reported that when Kelly came to the hospital the stretcher carrying him slipped to the floor, and he said, “This is my last slide.”28

Kelly was given oxygen. His health was front-page news in the Boston papers, which reported on Wednesday night that he was improving. The snowstorm prevented Galvin from contacting Agnes until Thursday morning. She started for Boston, but did not make it in time. By Thursday afternoon it was clear that the pneumonia was winning. A priest from St. James Catholic Church administered the last rites. Around 6 P.M. on Thursday, Kelly roused himself to say, “Well, I guess this is the last trip.”29 At 9:55 P.M. on Thursday, November 8, 1894, King Kelly died at the age of 36.

Kelly’s unexpected death was front-page news in every National League city. Agnes arrived on Friday afternoon and arranged to bury him in Boston, the city that loved him. By some estimates, 7,000 people attended Kelly’s funeral on November 11. His song, “Slide, Kelly, Slide,” was recorded by several artists on records, and remained a popular American tune into the 1920s. In 1945 he was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Kelly did as much as any other player to popularize professional baseball in the nineteenth century. His popularity transcended the game and became part of popular culture. He had a large effect on the game. It was said that half the rules in the baseball rulebook were rewritten to keep Kelly from taking advantage of loopholes. He played the game with gusto and looked for every edge he could get to win, and his teams won eight championships in 16 years. We are not likely to see a player like King Kelly again.

An updated version of this article was published in “The Glorious Beaneaters of the 1890s” (SABR, 2019), edited by Bob LeMoine and Bill Nowlin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted the following:

Spalding, A.G. Spalding’s Base Ball Guide 1886 (Spalding Books, 1886), 18-67.

Voigt, David Q. American Baseball: From Gentleman’s Sport to the Commissioner System (University Park, Pennsylvania: Penn State University Press, 1983).

Seymour, Harold. Baseball: The Early Years (New York: Oxford University Press, 1960).

Thorn, John. Baseball in the Garden of Eden: The Secret History of the Early Game (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2011).

Palmer, Pete, and Gary Gillette, eds. The Baseball Encyclopedia (New York: Barnes and Noble, 2004).

Notes

1 Mike “King” Kelly, Play Ball, Stories of the Ball Field (Boston: Emery & Hughes, 1888, issued digitally in 2008), Chapter 2. (Online version used for this article offered only chapter numbers.)

2 Kelly, Chapter 3.

3 Marty Appel, Slide, Kelly, Slide: The Wild Life and Times of Mike “King” Kelly (Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, 1996), 198.

4 Appel, 29.

5 Appel, 30.

6 Kelly, Chapter 4.

7 Adrian “Cap” Anson, A Ball Player’s Career (Chicago: Era Publishing, 1900), 115-116.

8 Appel, 45.

9 Appel, 48.

10 Appel, 58.

11 Appel, 72.

12 Appel, 78-83.

13 Appel, 87.

14 William T. Ellis, Billy Sunday, The Man and His Message (Dayton, Oho: Thomas Manufacturing Co, 1914), Digital Edition, Chapter 4.

15 Appel, 103-104.

16Kelly, Chapter 16.

17Anson, 117.

18Appel, 122.

19 Appel, 123.

20 Kelly, Chapter 17.

21 Appel, 135.

22 Mark Lamster, Spalding’s World Tour: The Epic Adventure That Took Baseball Around the Globe — And Made It America’s Game (New York: Public Affairs Press, 2006), 26.

23 Appel, 149.

24 Appel, 150.

25 Appel, 150-152.

26 Appel, 157.

27 Appel, 173.

28 Appel, 184.

29 Appel, 186.

Full Name

Michael Joseph Kelly

Born

December 31, 1857 at Troy, NY (USA)

Died

November 8, 1894 at Boston, MA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.