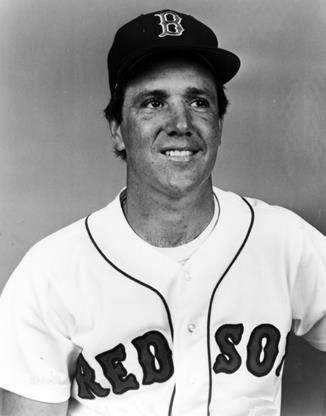

Marty Barrett

1986 – a season that tugs at the heartstrings of every Boston Red Sox fan who watched and listened to the American League Championship Series and the World Series. The World Series was a classic seven-game affair. If the Red Sox had kept a two-run lead going with two outs in the bottom of the 10th inning against the Mets at Shea Stadium in Game Six, Marty Barrett would have been the MVP of that game as voted by the NBC announcers. In the Series he had a .433 batting average, in 30 at-bats, and an on-base percentage of .514. Now, as Paul Harvey would say: The Rest of the Story.

1986 – a season that tugs at the heartstrings of every Boston Red Sox fan who watched and listened to the American League Championship Series and the World Series. The World Series was a classic seven-game affair. If the Red Sox had kept a two-run lead going with two outs in the bottom of the 10th inning against the Mets at Shea Stadium in Game Six, Marty Barrett would have been the MVP of that game as voted by the NBC announcers. In the Series he had a .433 batting average, in 30 at-bats, and an on-base percentage of .514. Now, as Paul Harvey would say: The Rest of the Story.

Marty Barrett was born on June 23, 1958, in Arcadia, California, a Los Angeles suburb, one of seven children of Charlotte and Randy Barrett. Of his five brothers, four played college or professional baseball: Charlie (born in 1955) played in the Los Angeles Dodgers farm system; Tommy (1960) played with the Phillies and Red Sox; Joe (1964) played at the University of Nevada Las Vegas; Andy (1966) played at Mesa (Arizona) Community College. John, born in 1954, did not play in college or the pros. Their sister, Susie (born in 1962) was a cheerleader.

Randy Barrett, who was a firefighter, moved the family to Las Vegas to find work when Marty was very young. Marty would play “ball” in the living room with his two older brothers and his brother Tommy. When Marty was 10 years old, he was playing on a 10-11-year-old team, and continued to play, often with boys a year or two older. By the time he was 15, he was playing on the Rancho High School varsity team, which won the state championship in 1974 and 1976. On the Rancho American Legion team, his coach was Manny Guerra, a longtime scout for the St. Louis Cardinals. Nine of his players made it to professional baseball, including Marty and Tommy, Mike Maddux, and Mike Morgan.1

Undrafted out of high school, Marty Barrett enrolled at Mesa Junior College, where he played baseball from 1976 to 1978. In 1979 he attended Arizona State University, where among his teammates was future major leaguer Hubie Brooks. During his college years, he played for Rod Dedeaux, the legendary coach of the University of Southern California, in a baseball tour of Japan. He also played summer ball in Anchorage, Alaska, with future major leaguers Tim Wallach and Mike Boddicker.

Barrett was selected by the Red Sox as the first pick of the first round of the now defunct secondary draft in June 1979. Red Sox scout Ray Boone is credited with the signing.2 Barrett’s first minor-league stop was at Winter Haven in the Class-A Florida State League in 1979, hitting .298 with a .719 OPS. The next season at Double-A Bristol, he batted .274 with a .677 OPS, and stole 22 bases.

In 1981 Barrett moved up to the Triple-A Pawtucket Red Sox, where he hit a home run in his first at-bat. The team, managed by Joe Morgan, included a number of players who went on to star in the majors – Wade Boggs, Rich Gedman, Bruce Hurst, and Bobby Ojeda.

Early in his time in Pawtucket, Barrett participated in the longest game in the annals of Organized Baseball. It began on April 18, 1981. The night was cold in Pawtucket, a 12-to-20-degree chill factor as the game wore on, and to keep warm players started fires in trash cans. Pawtucket trailed 1-0 in the bottom of the ninth inning, but tied the score on a sacrifice fly by Russ Laribee. Barrett remembered the Rochester relief pitcher throwing nine no-hit innings and the umpires having difficulty reaching the league president. (The Rochester pitcher, Jim Umbarger, actually pitched 10 no-run innings, the 23rd through the 32nd, giving up four hits.) Barrett had two hits in 12 at-bats.

Finally, at 4:00 A.M. the game was suspended. It was completed on June 23 while major-league baseball players were on strike. Media people were on hand in Pawtucket from as far away as Japan on the 23rd, as this was the “only interesting game in town.” Barrett remembered this as a “neat atmosphere” with a “nice spread” of food.3 Rich Gedman, Bruce Hurst, Luis Aponte, Mike Smithson, and Julio Valdéz were other future major leaguers who played in the game. Rochester pitcher Steve Grilli hit Barrett with the first pitch in the bottom of the 33rd inning. Future major leaguer Chico Walker executed a hit-and-run play that moved Barrett to third base, and Dave Koza singled him in for the winning run,

In 1982 Barrett spent his first spring training with Boston but with Jerry Remy as the starting second baseman for the Red Sox, Barrett spent the season with the PawSox again. After batting a team-leading .300, he was called up to the Red Sox on September 6. He got into eight games, with his first major-league hit coming off Mike Caldwell on September 22, but it was his only hit that season, as he finished 1-for-18. In the season’s final series, against the Yankees, he went 0-for-14.

In 1983 Barrett started the season in Boston, mostly playing as a defensive replacement, then was sent down to Pawtucket again. He was recalled near the end of June, ultimately appearing in 33 games and going 10-for-44 at the plate. He spent the entire 1984 season with Boston, taking over from Jerry Remy at second base and getting into 139 games for manager Ralph Houk. He batted .303 with 45 RBIs. His first career homer came on May 11, 1984, off Larry Gura of the Kansas City Royals.

Barrett was a right-hander, 5-feet-10 and listed at 175 pounds. The hidden-ball trick is one of his claims to fame. Joe Morgan, his manager at Pawtucket, taught him the trick. As an example: In 1981 he pulled off the hidden-ball trick on Bobby Bonner of the Rochester Red Wings. Barrett made the putout at first on a sacrifice bunt, and kept the ball. (This is where the ball is hidden.) The pitcher stood off the rubber with his back to first, and Barrett said to the runner, now at second, “Let me clean off the base.”

Barrett said he executed the hidden-ball trick about five to seven times in the minor leagues.4 He pulled it off three times in the major leagues with Red Sox, doing it twice in two weeks against the California Angels in 1985. In Anaheim on July 7, he tricked Bobby Grich, who was on first base, by pantomiming a throw to Glenn Hoffman, the Red Sox shortstop. On the 21st, in Boston, he pulled the same trick on Doug DeCinces, the Angels’ third baseman. (DeCinces had been needling Bobby Grich on the plane ride to Boston about how Grich had fallen for the hidden-ball trick. Naturally, Grich took a little satisfaction when DeCinces himself became a victim.) After Barrett performed the trick one more time, the umpires started to call time outs after the play was considered to be finished. Barrett felt that if he attempted to pull off the trick, again, he would make the umpires “look bad.”

By 1984 Barrett was already being favorably described as being an Eddie Stanky type of player, with more ability, by Detroit Tigers manager Sparky Anderson. Bill Buckner, who came to the Red Sox from the Chicago Cubs, in a May 1984 deal for Dennis Eckersley, gave Barrett the moniker of “Dekemaster” for his ability to pull off the hidden-ball trick, as well as fooling some baserunners into believing that a pitch had been fouled off.5

By 1985 Barrett was already receiving accolades as a player who got the most out of his physical and mental capabilities. Teammate and keystone partner Glenn Hoffman called him very smart and cagey.6 Coach Tony Torchia said Barrett understood that in a hit-and-run situation, he had to manipulate the bat to somehow meet the ball to protect the runner.7 In 1985 Barrett’s batting average dipped to .266 but he had a .987 fielding percentage and 56 RBIs to his credit. His lifetime fielding percentage was .986.

Everything went right in 1986. Barrett batted .286, the Red Sox with a career-high 15 stolen bases, and led the American League with 18 sacrifice bunts. He was “hot” for two to three weeks during the American League Championship Series and the World Series, against the New York Mets. In Game Six of the World Series, with the Red Sox up three games to two, Barrett’s single drove in a 10th-inning run that put the Red Sox ahead 5-3 and seemed to ice their Series triumph. But with two outs in the bottom of the 10th and the Series seemingly over, there came three or four bloop hits in a row. Future Hall of Famer Gary Carter flipped a hit into left field. Kevin Mitchell hit a bloop to center. Ray Knight fisted a pitch over Barrett’s head. Then, of course, there came the sinker away and the Mookie Wilson groundball the skittered under Bill Buckner’s glove. The Mets won the World Series in the next game.

In October 2014, Barrett reflected on Game Six of the 1986 World Series. He said it was manager John McNamara’s call to remove pitcher Roger Clemens for a pinch-hitter in the top of the eighth with the Red Sox leading 3-2. Most Red Sox players were upset with the wild pitch that allowed Mitchell to score the tying run in the bottom of the 10th. Prior to Mookie Wilson’s groundball, Barrett was trying to position himself to attempt a pickoff play on the runner at second base. Commenting on Mookie Wilson’s grounder, Barrett said, “What goes around comes around, but I didn’t think it would come around this quick.” He was referring to the fact that the Red Sox had advanced to the World Series on similar dramatics – Dave Henderson’s home run that pulled the Red Sox back from defeat in the ALCS.

Interestingly, in 1986, Barrett had not hit well against the Angels, hitting .188 (9-for-48). What made him so valuable in the American Championship Series? He watched videotapes of the season before the ALCS. He indicated that he had learned a lot from those tapes.8 Sure enough, with five RBIS and a .367 average, Barrett was named the MVP for that unforgettable series against the Angels. (He donated the Chevrolet Sportsvan he received as the MVP to the Childhood Cancer Association of Southern Nevada.)

Barrett hit a solid .293 in 1987, and then .283 with a career-high 65 RBIs in 1988. On June 16, 1988, he stole home in a game at Baltimore. In the fourth inning of a scoreless game, Barrett singled leading off the inning against Jeff Ballard. He was on third base with two outs. Mike Greenwell was the Red Sox batter. At an opportune moment Barrett dashed home. His steal of home gave the Red Sox the early lead, but Baltimore eventually won, 8-4. The Red Sox made the postseason again in 1988 but were swept in four games by Oakland; Barrett was just 1-for-15.

In 1989 Barrett signed a big contract with the Red Sox but suffered his first serious injury when he tore the anterior cruciate ligament in his right knee on June 4. He missed 55 games after the injury and, for the season, played in only 86 games. The next season, 1990, was his last with the Red Sox. He played in only 62 games, batting .226. He was ejected from Game Four of the American League Championship Series, against Oakland. Roger Clemens had been ejected in the bottom of the second by umpire Terry Cooney. After a pitch that Cooney called a ball, Clemens erupted and shouted expletives. Cooney promptly tossed him. Barrett was so incensed that he started to throw things on the field, so he was ejected as well.

After the season Barrett was released by the Red Sox. He signed on with the San Diego Padres, but played in only 12 games (3-for-16) before being released in June 1991. His time in the majors was complete. He played 16 games for Las Vegas, batting .319, but then retired from the game.

In 1992 Barrett sued Dr. Arthur Pappas, the Red Sox’ team physician and a limited partner in the Red Sox ownership, for malpractice. This stemmed from the torn ACL that he had endured in the summer of 1989. Dr. Pappas advised Barrett to do physical therapy and rehabilitation. This had allowed him to return to the field in six weeks, but in 1995, when the verdict was read, it was concluded that he should have had surgical reconstruction of the knee. He received $1.7 million in back salary.9

Barrett spent some time in 1995 managing Rancho Cucamonga in the Class-A California League, but despite opportunities to manage elsewhere, elected to stay at home with his family. Interestingly, in an interview in the spring of 1987 discussing his three-year, $2 million contract, he said he loved to spend time with his family. That may explain why he decided to get out of Organized Baseball in 1996 and help to coach Little League baseball back home in Las Vegas.10

In March 2014, in an appearance in West Hartford, Connecticut, Barrett opined on a number of subjects in an interview.

He told the interviewer, Alan Cohen, that he liked the idea of instant replay. It would keep the umpires focused and not allow game outcomes to be determined by “brutal calls.” Replay may cut down on arguments, shortening the length of games. He also noted, “As you look back, you realize how dumb you were when you first got big money at a young age. Kids need more tutoring at handling money.”

Barrett said his favorite ballparks to hit in were Anaheim Stadium and Baltimore’s Memorial Stadium. On the subject of steroids, he said he felt that ownership turned a blind eye. Growing up, his favorite player was Pete Rose and he said Rose should be admitted to the Hall of Fame. His current favorites were Bryce Harper and Dustin Pedroia, who “dives for everything” and shows “unmatched drive and desire.”

The toughest pitcher during Barrett’s time in the majors was Jack Morris. Although he tipped his pitches, he had excellent control. Barrett spoke highly of his batting coach, Walter Hriniak, who stressed the importance of taking batting practice seriously, and stressed work ethic, even more than technique.11

Barrett and his wife, Robin, had three children: Eric, Katy, and Kyle. Katy, a fine athlete in her own right, is an assistant golf pro in the Las Vegas area. Robin Barrett sold real estate, and Marty owned rental properties. In 2014 he was still active with baseball in Las Vegas, where he coached a team of 14-year-olds. Barrett began coaching in 1996, when his son Kyle recognized him from his baseball cards more than in person. It was at that point that he decided to leave Organized Baseball; he had been with the Rancho Cucamonga Padres. There is still a Marty Barrett Little League in North Las Vegas. Marty had provided his name to the Little League, in the 1990s, because it was dying at the time in North Las Vegas.

Barrett said he played golf as much as possible, and at one time had a 3-handcap. He said he considered former teammate Jim Rice the best golfer among baseball players.12

Sources

Marty Barrett was a pleasure to talk with in October of 2014. He gave an hour and a half of his time to talk with me. He and I had never met before. My friend Kevin Hunt, an anthropology professor at Indiana University, helped arrange the interview. SABR member Alan Cohen provided much help, as well. His article “Marty Barrett at World Series Club” was a great help and is cited in this article.

Notes

1 lasvegassun.com/news/2008/jan/24/rancho-high-alums/.

2 Nick Cafardo, Lewiston (Maine) Daily Sun, June 24, 1988.

3 Marty Barrett interview with author, October 14, 2014.

4 Barrett interview.

5 Associated Press, Bangor Daily News, March 4, 1985, 12.

6 Mike Fine, Lewiston (Maine) Daily Sun, June 26, 1985.

7 Ibid.

8 Associated Press, Bangor (Maine) Daily News, October 9, 1986, 17.

9 Associated Press, Lewiston (Maine) Sun Journal, October 26, 1995, 4C.

10 Nick Cafardo (Patriot Ledger Sports Service), “Barrett is cautious, conservative – and totally dependable,” The Telegraph, Nashua, New Hampshire, March 24, 1987, 11. news.google.com/newspapers?nid=2209&dat=19870324&id=U09KAAAAIBAJ&sjid=zJMMAAAAIBAJ&pg=2824,8086749. Accessed February 10, 2015.

11 Alan Cohen, “Marty Barrett at World Series Club,” December 11, 2014. linkedin.com/pulse/marty-barrett-world-series-club-alan-cohen.

12 Todd Dewey, “Marty Barrett remembers the Sox’ last streak and talks Vegas golf,” lasvegasgolf.com/departments/features/marty-barrett-profile.htm, October 12, 2003. Accessed January 12, 2015.

Full Name

Martin Glenn Barrett

Born

June 23, 1958 at Arcadia, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.