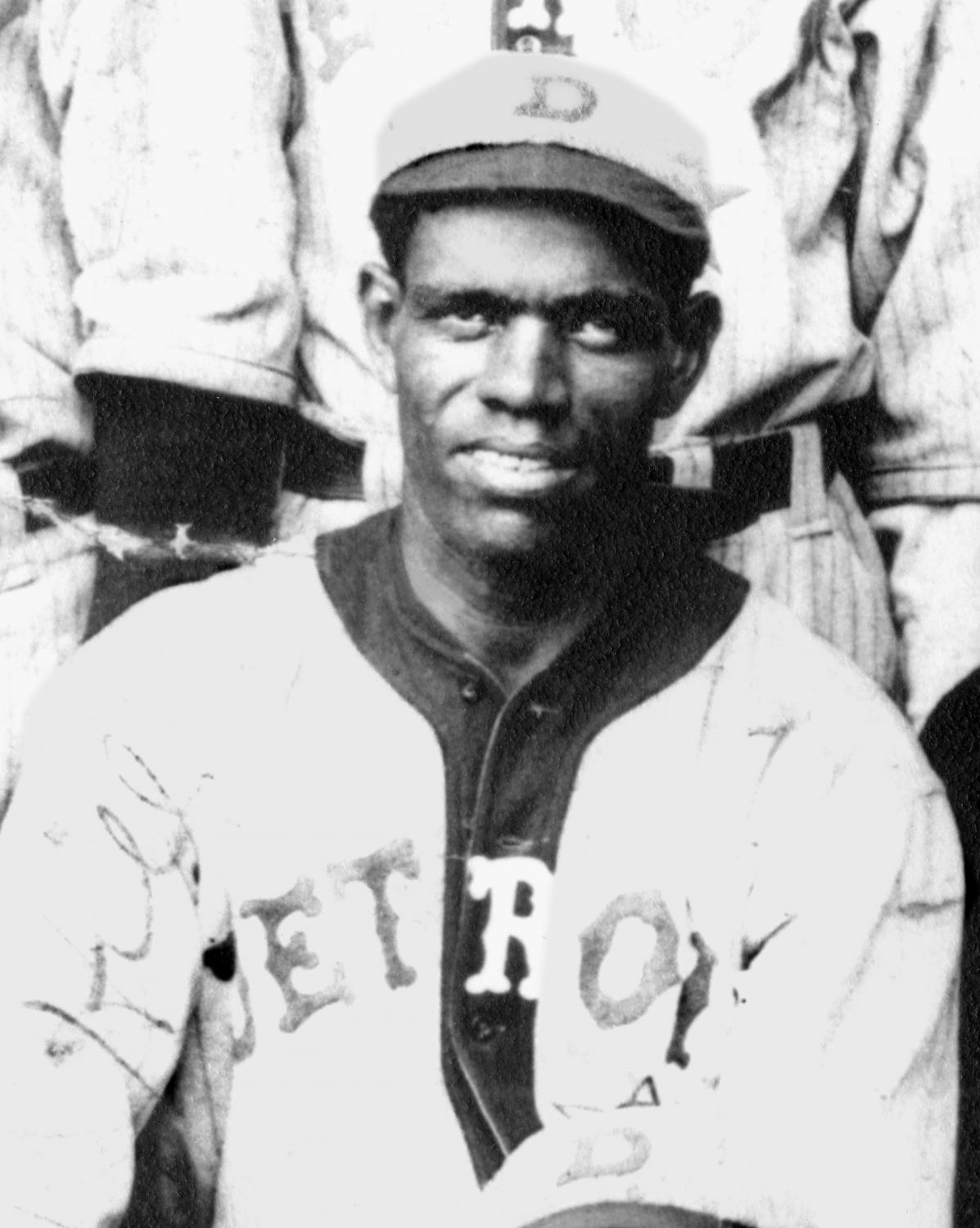

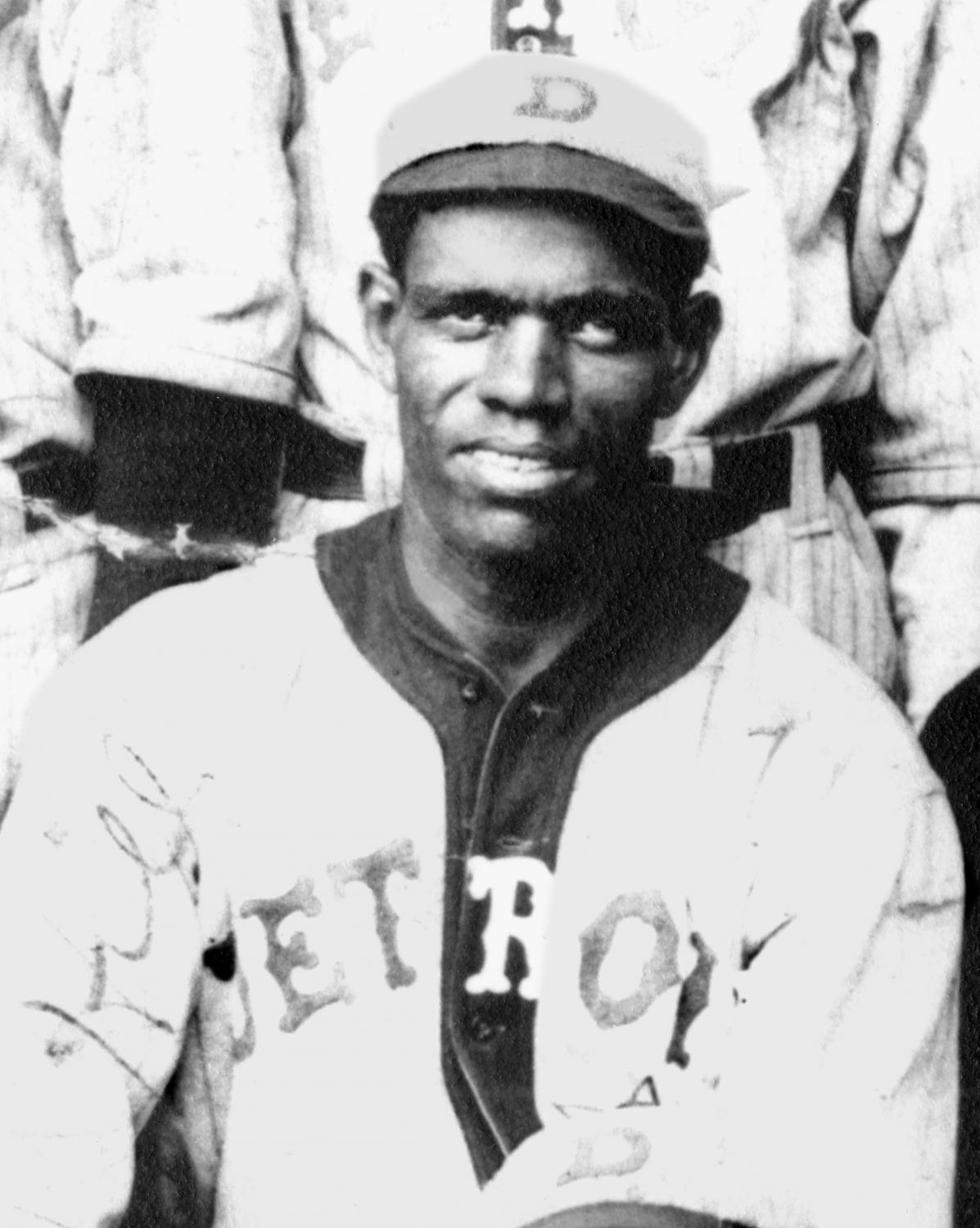

Pete Hill

“Pete Hill was the first great outfielder in black baseball history,” suggests baseball historian Lawrence Hogan.1 The left-handed Hill was a five-tool star with several famed independent African-American teams: the Philadelphia Giants (1904 to 1907), Leland Giants (1908 to 1910), and Chicago American Giants (1911 to 1918). He then slugged his way to Ruthian heights as the Detroit Stars’ player-manager in 1919, before his professional career wound down in 1925. Crowning recognition of his accomplishments came in 2006, when he was inducted into Baseball’s Hall of Fame.

“Pete Hill was the first great outfielder in black baseball history,” suggests baseball historian Lawrence Hogan.1 The left-handed Hill was a five-tool star with several famed independent African-American teams: the Philadelphia Giants (1904 to 1907), Leland Giants (1908 to 1910), and Chicago American Giants (1911 to 1918). He then slugged his way to Ruthian heights as the Detroit Stars’ player-manager in 1919, before his professional career wound down in 1925. Crowning recognition of his accomplishments came in 2006, when he was inducted into Baseball’s Hall of Fame.

John Preston Hill was born in the Culpeper County, Virginia, hamlet of Buena, on October 12, 1882. Two brothers, Jerome and Walter, preceded him. His parents, “Ike” and Elizabeth “Lizzie” (née Seals) Hill, were Virginia natives. Early in his life, his father seemingly disappeared, with county records suggesting he may have died in 1887. Soon afterwards, his mother boarded a northbound train with her young sons and settled in Pittsburgh.2

Hill’s professional baseball career is sometimes cited as beginning with the Pittsburgh Keystones in 1899 then, after two years with that squad, moving on for a stint with the famed Cuban X-Giants.3 This storyline seems questionable. At the time of the 1900 census, the teenager lived with his mother, brothers, and stepfather in Pittsburgh, and worked as a day laborer. He may well have played with the Keystones at some point – the scant coverage the era’s newspapers granted Black baseball makes any sweeping conclusions to the contrary ill-advised – but none of the limited references to this team mention a “Hill.”4

Perhaps his professional debut instead came in 1901. That January a “J.P. Hill” was included in a roster of Black players signed by the Golden Slides club.5 Yet box scores for the Slides are elusive. The Barnes Colored Americans, organized by Bud Fowler, also debuted in Pittsburgh that season. Although not listed in the squad’s opening roster, a “Hill” played left field and homered in their 9-7 loss to a Monaca team on July 1.6

Neither the Golden Slides nor the Colored Americans apparently lasted past 1901. Pittsburgh newspapers reference a “Hill” in the Matthews Colored Amateurs’ roster in 1902, and the (likely African-American) Iron City’s roster in 1903.7 Again, box scores for either team are elusive. Meanwhile, the “Hill” playing for the X-Giants in this span was infielder Johnny Hill.8 The X-Giants toured western Pennsylvania twice in 1902 and once in 1903, and quite possibly scouted local teams. But, like so much of Pete Hill’s development, this remains a mystery.

Somehow, by the time the 1904 season dawned, Hill had come to the attention of the Philadelphia Giants. Owned by newspaperman H. Walter Schlichter and managed by Sol White, the team’s 1903 campaign had culminated with a key series loss to the X-Giants. That off-season, the “Phillies” induced several “Cubes” to sign with them: infielder Charlie Grant, outfielder Andrew “Jap” Payne, and pitcher Andrew “Rube” Foster. Hill joined these newcomers in April 1904. He initially played left field and batted in the bottom third of the order. But he soon took over center field and regularly batted third, fourth, or fifth. A season highlight: against a Hoboken team on August 14, Hill contributed four hits and the sole run scored as Foster outdueled semipro ace Ernie Lindemann in a 1-0 thriller.9 That fall, the Phillies avenged their series loss to the Cubes the year before, taking two of three games in a rematch between the teams. Hill struggled, contributing only one hit in the three contests.10

The Phillies again recruited that offseason, adding infielder Grant “Home Run” Johnson and pitchers Emmett Bowman and Dan McClellan. The resulting 1905 squad proved a juggernaut, achieving a 128-23-3 record and earning a place among the finest African-American teams of the Deadball Era, if not all time.11 Per baseball historian Phil Dixon’s research, from the 133 games with box scores (and nine of these lacked summaries detailing extra-base hits and stolen bases), Hill banged out 198 hits, including 37 doubles, 11 triples, and 10 home runs, while stealing 34 bases.12 Then, concluding a lengthy barnstorming campaign – that for Hill had begun in the Florida Hotel League at the beginning of the year – he finished 1905 as the leading offensive star for an X-Giants squad playing in the Cuban Winter League.13

The Phillies remained dominant in 1906, both against other Black teams and White semipro and minor-league competition. That October they met the barnstorming Philadelphia Athletics for two games. The Mackmen took the pair. Facing Eddie Plank and Rube Waddell, Hill contributed three of the Phillies’ seven hits in the matches.14 Per Seamheads’ Negro League database, Hill amassed a BA/OBP/SLG line of .327/.417/.423 (and an OPS+ 217) in 31 career games against major-league teams. Moreover, as baseball historian Gary Ashwill illustrates, in Hill’s extended play in Cuba (against both Cuban teams and exhibitions against major-league teams), he fared strikingly better than Rafael Almeida and Armando Marsáns, two light-skinned Cubans who went on to play in the majors.15

Yet the Phillies’ decline seemed inevitable. “The 1905 Philadelphia Giants, for all their impressive firepower, were a precarious financial balancing act;” observes Ashwill, “they were too dominant, and had trouble booking enough truly high-profile games against worthy opponents.”16 Johnson left prior to the 1906 season, and Bill Monroe as it opened. Following that campaign, owner Schlichter cut some salaries, and instituted other cost-saving measures at his players’ expense.17 Foster, seeking a fairer deal, recruited several Phillies that offseason to join him with the Leland Giants, one of Chicago’s leading Black teams, owned by ex-player Frank Leland. After another fine campaign with the Phillies in 1907, Hill left to join the Lelands.

For the next 11 seasons, he played for Foster. The pitcher transitioned to a successful magnate role, finding increasing autonomy and profit for his squads. Hill was his captain and, in his absences, the de facto manager.18 Contrasts distinguished the two. Foster conveyed bravado. Hill was described as “quiet” and “modest.”19 Foster issued sweeping pronouncements regarding the past, present, and future of Black baseball. Hill’s press output was crisp and minimal. Foster was physically imposing. Hill stood 5-foot-8 and weighed 170 pounds.20 Hill was also a family man, having married Gertrude Lawson in either 1906 or 1907. A son, Kenneth, arrived in 1910.

The highlight of the Leland Giants’ 1908 season was a planned seven-game series with the Philadelphia Giants. The teams split the first six games, with Hill contributing eight hits, including three doubles and one triple, against his former teammates.21 The seventh, deciding game never occurred. In 1909 the Lelands easily captured Chicago’s semipro City League pennant with a 31-9 record.22 Hill played in 37 of these matches, hitting .321 and posting a .429 slugging percentage (in both cases, second among Leland regulars).23 Yet the team lost a three-game rematch against the Phillies that August and a three-game set against the Chicago Cubs in October. In each of these series, Hill collected only two singles.24

Leland and Foster split at the end of the 1909 season. Foster retained rights to the team’s name and, that offseason, recruited with determination. Catcher Bruce Petway, shortstop John Henry Lloyd, and outfielder Frank Duncan were lifted from the Phillies. Grant Johnson came over from the Brooklyn Royal Giants. Pitcher Frank Wickware was added to the rotation.

With the Phillies, Hill spent stretches in both left and center field. Upon arriving in Chicago, he became Foster’s center fielder. Duncan took over left field in 1910; “Jap” Payne remained in right. The trio stayed in place for the next three seasons.

Defensively, Hill impressed onlookers with his heady play and athleticism. In a 1910 match against the semipro Gunthers, “Pete Hill pulled off the unusual trick of dropping an outfield fly purposely with men at first and second in the sixth inning. He picked the ball up and threw to third and the ball was sent back to second for a double play that retired the side.”25 Against the Cuban Stars in 1911, Hill was praised for “cutting off many well-meant hits by sensational running catches.”26 In 1912, against a Tufts-Lyons opponent in Southern California, Ivy Olson took flight from second base on a single to deep center and seemed “a cinch” to score. “Hill, however, upset all calculations with a sensational throw to the plate. His peg came in fast and true, and Petway, throwing himself in front of the sliding Olson, cut him off within a foot of his goal.”27

Hill prospered from the revitalized lineup. Hitting second or third in the order, and sandwiched between Duncan and Johnson, he enjoyed one of his finest offensive seasons in 1910. By mid-August, per contemporary sources, he had 17 home runs and 16 triples to his credit.28 Seamheads, from a limited sample of 22 documented games, credits him with a gaudy BA/OBP/SLG line of .511/.540/.830 (and an OPS+ 319).

Foster next partnered with John C. Schorling. For 1911, the squad was renamed the Chicago American Giants and played their home games at Schorling Park. The new field was spacious, with its fences 350 and 360 feet away down the lines and 450 feet away at dead center.29 Hill’s reputation turned from slugger to one of baseball’s finest line-drive hitters. In one regular-season stretch during 1911, he reportedly hit safely in 115 of the Americans’ 116 games. This seems doubtful: José Méndez alone shut him down twice that summer.30 But even .400 hitters suffer oh-fers, and this was quite possibly Hill’s status at the beginning of the decade.

Like many of his teammates, Hill possessed exceptional speed: at an 1911 “Athletic Field Day” competition, he was timed circling the bases in 14.4 seconds.31 His ability as a lefthanded batter to drag bunts was heralded.32 He routinely took extra bases with his aggressiveness, drawing contemporary comparisons to Ty Cobb.33

Although the team suffered some setbacks, most notably losing a lengthy series to the New York Lincoln Giants in 1913, they were likely the winningest of major western independent Black teams in this era.34 At home, the Americans could outdraw the Cubs and White Sox.35 By 1913, thanks to lengthy West Coast tours, they played over 200 games a year. Beyond this already impressive commitment Hill and several teammates also typically spent a winter month playing hotel ball in Florida.36

Challenges towards both Hill’s and the Americans’ preeminence came in mid-decade. A succession of Black outfield standouts – Judy Gans, Spottswood Poles, George Shively, and Cristóbal Torriente – had arrived in the previous half-dozen seasons. But arguably the greatest outfielder in pre-Integration Black baseball history, Oscar Charleston, debuted in 1915. His team, the Indianapolis ABCs, also toppled the Americans that season.

In Chicago, on July 18, a key series opened between the teams. With the affair knotted, 3-3, a “melee” broke out between the squads, and “the umpire and Pete Hill had an argument and the umpire jerks out a gun and hits ‘Pete’ over the nose.”37 The umpire promptly forfeited the game to Indianapolis. Foster and ABCs manager C.I. Taylor proceeded to squabble in print over what had transpired. But Indianapolis swept the series, despite Hill hitting two home runs in each of the final two matches.38

The teams continued to battle over the next several years. In October 1916 Indianapolis claimed “the colored baseball title of America” after winning five of nine games in a contested series with the Chicagoans.39 In 1917 the Americans dominated their rivals. The next season, although Foster’s squad again led the west, the ABCs won two matches, and gained a tie, in a three-game series played versus the Americans in Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field. Hill contributed two hits and three runs in the set. Charleston collected six hits and six runs.40

If Hill had been a .400 hitter at the beginning of the decade, in his final five years with the Americans, he may have been closer to a .300 hitter.41 As with the White major leagues – where runs-per-game plummeted from 4.5 in 1911 to 3.6 in 1917 – Black independents also scored less over this span. Data from the Seamheads’ database suggest these teams averaged 5.4 runs-per game in 1911, then 4.1 in 1917.42 Even more pronounced was the decline for the Americans. After the team averaged 5.7 runs in 1911, they scored only four per game in 1917.43

In part, the reasons for the offensive contraction in Black baseball likely paralleled those in the major leagues. For example, in 1942, Hill stated he could have “murdered” that era’s live balls, and recalled of the dead balls, “You had to put the wood on it sure enough.”44 But mushy baseballs, doctored pitches, and even park factors may not fully explain the Americans’ scoring decline.

The “small ball” that Foster, aided by captain Hill, refined may been motivated as much by the teams’ strengths as by necessity. Chicago not only possessed excellent team defense and strong starting pitching, but also a disciplined, speedy offensive attack. Cool Papa Bell, for example, recalled that Foster’s “favorite play was the steal and bunt. The runner on first would take off and the batter would bunt the ball so the third baseman had to field it. If he threw to first, the lead runner just kept going to third. If he held the ball, it was runners on first and second. It was a beautiful play and Foster’s team made it work over and over again. To make it work, his guys had to be able to really place their bunts. They used to practice for hours bunting the ball into areas Rube would mark off with chalk.”45

As the Americans evolved, Foster continued to seek a well-organized and economically viable Black baseball league. Detroit, whose African-American population grew from 5,000 in 1910 to 40,000 in 1920, was a fertile opportunity for such a circuit. Foster parted ways with Hill after the 1918 season, setting him up as manager of the new Detroit Stars, and seeding the new franchise with considerable talent. Chicago mainstays Duncan, Petway, and Wickware accompanied Hill to Detroit. Additionally, two newcomers to the Americans in 1918, first baseman Edgar Wesley and shortstop/pitcher José Méndez, were bequeathed to Hill.46

The Stars drew an impressive 3,500 fans on April 20, 1919, for their home debut at Mack Field, as they beat the semipro Maxwells, 8-4. Hill, playing center field and batting third, went 2-for-4.47 A month into the campaign they remained unbeaten.48 In mid-June, visiting Schorling Park, Detroit lost three of four against Chicago. Hill contributed four hits and two runs in the series; Foster’s new center fielder, Charleston, contributed six hits and six runs.49 The teams met again in Detroit for a seven-game set a month later. After losing the first two games, the Stars won the remaining five.50 10,000 fans attended the second game, at Navin Field. Hill batted 10-for-25 in the series, with a double, two triples, and three home runs.

Such slugging was indicative of Hill’s 1919 season. Mack Field possessed a friendly right-field fence that rewarded his left-handed bat.51 But his homers were often anything but cheap. On April 27, Hill “performed a feat duplicated only once before at Mack Park” since its 1915 opening as he “drove the ball far over the centerfield fence.”52 He repeated the accomplishment on May 18.53 On June 8, his drive over the right-field fence “was the longest ever seen at Mack Park.”54 Then, on an eastern road trip, “Pete Hill hit the longest home run ever seen in the Atlantic City park” against the Bacharach Giants’ Dick Redding on July 16.55

Hill finished the campaign with 28 home runs, one less than Babe Ruth hit in his breakthrough final season with the Red Sox.56 It was his most dominant offensive season since 1910 with the Lelands. The Stars scored 5.6 runs per game, well ahead of the Black independent teams’ average of 4.7.57 Like Ruth, Hill led baseball out of the Deadball Era. Detroit finished alongside Chicago atop the western standings.

In 1920, following years of Foster’s efforts to build a Black league, the Negro National League was formed, with the Stars as a charter member. On May 15, Hill homered in his first NNL at-bat against the visiting Cuban Stars, leading Detroit to a 5-2 victory.58 Yet, for most of the season, teams worked around Hill. “The slugging right fielder of the Stars, P. Hill, was the particular victim of the veteran manager’s wiles,” a reporter noted of C.I. Taylor’s strategy as Indianapolis took a game from Detroit on July 3, “He was given three bases on balls, twice in critical moments when a hit would have meant a run.”59 Analyzing 45 documented games, Seamheads credits Hill with the same number of hits (38) as walks. He also battled injuries, as did several other key Stars.60 Although his home run count plummeted, Hill still produced a strong offensive campaign. But in the inaugural NNL pennant race, Chicago comfortably outpaced Detroit.

The Stars raced to the front of the NNL pack to begin the 1921 campaign, compiling a 15-6 league record by early June.61 But St. Louis took four straight games at Mack Park in early July, and Hill’s team then sank further during a lengthy road trip.62 He again contributed another plus season offensively, yet Detroit finished below .500. Owner Tenny Blount dismissed him at the end of the season.

Hill signed on with Chappie Johnson’s semipro Philadelphia Royal Stars for the 1922 season. Johnson, who had been a teammate of Hill’s during his “rookie” year with the Phillies in 1904, named his friend captain. The Royal Stars’ lengthy barnstorming tours of the Northeast must have reminded Hill of his Phillies years.63 He returned to the NNL in 1923 to manage the Milwaukee Bears. The “young and inexperienced” squad finished in last place.64 “Old timers say Pete was a whale of a player,” a correspondent wrote in January 1924, “but newer fans who saw Pete attempt to manage the Milwaukee club, knew his days were about ended as a manager or a player in fast company.”65

“It is true that I am slowing up as a player,” Hill responded, “but I do take exception to being ‘through as a manager.’” He added, “I have never knowingly made an enemy in baseball.”66 If so, as he assumed the helm of the Eastern Colored League’s Baltimore Black Sox, he would soon find many.

The ECL, founded by Hilldale Club owner Ed Bolden in 1923, reflected Bolden’s animosity toward Foster.67 Eastern raids upon the NNL helped to ensure a successful inaugural campaign for the league. Yet Baltimore finished in the ECL cellar that season, leaving owner Charles Spedden anxious for improvement in 1924. To this end, Hill vigorously raided NNL teams. Most notably, he enticed three ABCs: second baseman Connie Day, third baseman Henry Blackmon, and right fielder Crush Holloway. The NNL reportedly “blackballed Pete Hill from future participation in any league clubs as a result of his actions.”68

Hill’s Black Sox kept the Hilldales at bay until mid-July, when the Philadelphians took over the league lead.69 Baltimore eventually finished the 1924 season in second, several games behind the Hilldales. Hill, as he had in Milwaukee, came off the bench occasionally for an outfield start, or to pinch hit.

Disappointed with the 1924 finish, Spedden appointed slugger John Beckwith as Black Sox manager that offseason.70 Hill stayed on as the team’s business manager and occasional pinch hitter.71 In 1925 Baltimore fared little better under Beckwith and Spedden re-appointed Hill skipper in August.72 The team played poorly the rest of the way, and he was let go.

Hill moved to Buffalo that offseason, rooming with his old friend Grant Johnson.73 In 1926 they revamped the local Pullman Colored Giants team, calling it Pete Hill’s Colored Stars.74 In 1927, with the Colored Elks, he was still playing semipro ball.75 By this time he was likely divorced; Gertrude was in Chicago for the 1930 census.

He spent the remainder of his life in Buffalo, working as a porter on the Delaware, Lackawanna & Western Railroad. Hill died on December 19, 1951, of coronary thrombosis. His son, Kenneth, survived him and arranged for his father to buried in Holy Sepulchre Cemetery in Alsip, Illinois.76 He rests today under a headstone provided by SABR’s Negro Leagues Grave Marker Project.

Months after his passing, Hill was named to the second team of the famed 1952 Pittsburgh Courier All-America Baseball Team.77 Four decades later, baseball historian James Riley argued, “If an all-star team had been picked from the Deadball Era, Cobb and Hill would have flanked Tris Speaker to form the outfield constellation.”78 In 2006 Pete Hill was among 16 men and one woman elected to the Hall of Fame by the Special Committee on the Negro Leagues.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Hill’s file from the National Baseball Hall of Fame and the following sites:

digital.chipublib.org/digital/collection/examiner

Notes

1 Lawrence D. Hogan, Shades of Glory: The Negro Leagues and the Story of African-American Baseball (Washington, D.C.: National Geographic, 2006): 108.

2 Upon his induction into the Hall of Fame in 2006, Hill was believed to have been born as Joseph Preston Hill, on October 12, 1880, in Pittsburgh. Soon afterwards Patrick Rock and Gary Ashwill’s research suggested Hill’s given name, birth year, and birthplace were otherwise. Ashwill contacted Leslie Penn and her cousin Ron Hill (the player’s great nephew) with this evidence. Hill then emailed Rob Humphreys, editor of the Culpeper (Virginia) Star-Exponent. Humphreys assigned the story to local researcher Zann Nelson, who delved into local sources, and produced a revealing three-part story that appeared in December 2009. Hill’s Hall of Fame plaque was recast and unveiled on October 12, 2010. For an overview of this tale, see Kevin Kirkland, “Penn Hills Man Wins Battle with Baseball Hall of Fame for his Great-Uncle,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, August 8, 2010, https://tinyurl.com/y4r2oudt. For one of Gary Ashwill’s entries, see “Is Pete Hill’ Hall of Fame Plaque Wrong?” Agate Type, April 20, 2007, https://tinyurl.com/y49x3ve4. For Zann Nelson’s Culpeper Star-Exponent series, see “Correcting History,” December 29, 2009, https://tinyurl.com/y43f32as; “The Mystery Unravels,” December 30, 2009, https://tinyurl.com/y6a4x93y; and “Digging Deeper,” https://tinyurl.com/y4se5473, December 31, 2009. [All online sources accessed February 20, 2019

3 The source for this information may have been reporting late in Hill’s playing career. See “Black Sox Players, No. 1, Pete Hill, Manager,” Baltimore Afro-American, January 18, 1924. Also, an 1899 debut becomes less plausible once Hill’s birth year moved forward two years. Or more – as some of Nelson’s sources suggested an 1883 or 1884 date.

4 See for example the roster within “Afro-American Notes,” Pittsburgh Press, March 18, 1900.

5 “The Golden Slides Are Ready,” Pittsburgh Post, January 24, 1901. On the Slides being an African-American team, see “Among the Amateurs,” Pittsburgh Post, September 14, 1901.

6 “Monaca Wins a Good Game,” Pittsburgh Post, July 2, 1901. For Colored Americans background, see “Strong Colored Team,” Pittsburgh Post, April 16, 1901 and “Colored Champion Baseball Team,” Pittsburgh Post, April 19, 1901.

7 On the Matthews’ team, see “Pittsburg’s Big Colored Team,” Pittsburgh Post, March 8, 1902; “Colored Amateurs at Rochester,” Pittsburgh Post, April 27, 1902; “Colored Amateurs Want Games,” Pittsburgh Post, June 15, 1902. Iron City: “Amateur Notes,” Pittsburgh Press, March 29, 1903. On Iron City being an African-American team, see “Amateur Baseball Notes,” Pittsburgh Post, April 5, 1903.

8 There are 50-100 readily-available box scores for the X-Giants per season from 1900 through 1903. None of them list another “Hill” beyond the weak-hitting Johnny Hill who regularly played short or third.

9 “Hoboken Lost in Record Game,” Jersey Journal, August 14, 1904.

10 “Phila. Giants Trim Cuban X-Giants, Foster Fanning 18 Men at Plate,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 2, 1904; “Cuban X Giants Land 2D Game,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 3, 1904; “Phila. Giants Win Championship,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 4, 1904.

11 The team’s record per Phil S. Dixon, Phil Dixon’s American Baseball Chronicles – Great Teams: The 1905 Philadelphia Giants Volume III (Xlibris, 2010): 22-23.

12 Ibid., 33, 46-47, 56-57, 232.

13 For a Florida box score, see “A Palm Beach Fan Valentine,” Kentucky Post, February 14, 1905. For Cuban Winter League statistics, see Seamhards.com.

14 “Athletics Win in Chester,” Camden Daily Courier, October 13, 1906; “Rube Fans 18 Batsmen,” Camden Post-Telegram, October 15, 1906.

15 Gary Ashwill, “Fourth of July 1911,” Agate Type, July 4, 2011, https://tinyurl.com/y3eyrdzl.

16 Gary Ashwill, introduction to Sol White’s Official Base Ball Guide by Sol White (South Orange, NJ, Summer Game Books, 2014): xvii.

17 Larry Lester, Rube Foster in his Time: On the Field and in the Papers with Black Baseball’s Greatest Visionary (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2004): 29.

18 The earliest mention of Hill as captain identified by the author: Cary B. Lewis, “Baseball Gossip,” (Indianapolis) Freeman, May 28, 1910.

19 “Baseball,” (Chicago) Suburban Economist, August 26, 1910; “Scraps of Sport,” (Indianapolis) Freeman, June 27, 1908.

20 Possibly he was shorter. Late in his career, sportswriters called him “a small man” and “diminutive.” See “Briscoes to Play Pair of Games Here,” Jackson (Michigan) Citizen Patriot, August 7, 1921; Herman Appelman, “Amateur Ball,” Detroit Times, May 3, 1920.

21 “Leland Giants Take Game,” Chicago Tribune, July 28, 1908; “Get Even with Their Rivals,” Chicago Tribune, July 29, 1908; “Batting Rally in the Ninth Gives Leland Giants Game,” Chicago Tribune, July 29, 1908; “Victory for Leland Giants,” Chicago Tribune, August 3, 1908; “Trimming for ‘Rube’ Foster,” Chicago Tribune, August 7, 1908; “Another Game To Easterners,” Chicago Tribune, August 8, 1908.

22 “City League Ends Season Schedule,” Chicago Tribune, October 4, 1909.

23 Lester, Rube Foster in his Time, 40.

24 For the Phillies’ series, see Lester A. Walton, “In the Sporting World,” New York Age, August 19, 1909. For the Cubs’ series, see “City Champs Win from Lelands, 4-1,” Chicago Tribune, October 19, 1909; R.W. Lardner, “Foster Argues, Schulte Scores,” Chicago Tribune, October 22, 1909; R.W. Lardner, “Cubs Trim Giants in Final Game, 1-0,” Chicago Tribune, October 23, 1909.

25 “Gunthers’ Errors and Lelands’ 5-1 Win,” Chicago Examiner, May 16, 1910.

26 “American Giants Are Blanked by Cuban Stars,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 30, 1911.

27 “Giants Beat Nagle’s Men,” Los Angeles Times, November 11, 1912.

28 Cary B. Lewis, “Diamond Dashes,” (Indianapolis) Freeman, August 6, 1910; Cary B. Lewis, “Diamond Dashes,” (Indianapolis) Freeman, August 20, 1910.

29 Lester, Rube Foster in his Time, 56.

30 For Méndez’s success versus Hill, see “American Giants Are Blanked by Cuban Stars,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 30, 1911; “American Giants Win Then Tie Cuban Stars,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 11, 1911. For other instances of a Hill oh-fer in 1911, see “Giants Down Cuban Stars, 7-3,” Chicago Tribune, June 1, 1911; “Lincoln Giants Win Twice at American League Park,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 5, 1911; “American Giants Lose,” Chicago Inter Ocean, September 17, 1911.

31 Sylvester Russell, “Athletic Field Day,” (Indianapolis) Freeman, October 21, 1911.

32 Russell J. Cowans, “Thru the Sport Mirror, Detroit Tribune, August 19, 1933.

33 “Bots and Bingles,” Tacoma Daily Ledger, April 14, 1915.

34 Seamheads’ partial season records support such a conclusion.

35 Robert Charles Cottrell, The Best Pitcher in Baseball: The Life of Rube Foster, Negro League Giant (New York: New York University Press, 2001): 63.

36 For instances of his Florida play, see “Baseball Season Ends on Florida Fields,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, March 18, 1914; “Ball Players Go South,” (Indianapolis) Freeman, January 16, 1915.

37 “American Giants in Fierce Riot at Hoosier City,” Chicago Defender, July 24, 1915.

38 Cottrell, The Best Pitcher in Baseball: 92-93.

39 “Colored Title Won by A.B.C.s,” Indianapolis Star, October 30, 1916.

40 “Giants-A.B.C. Deadlocked in Eleven Innings,” Pittsburgh Post, July 26, 1918; “Colored Series to Close Today,” Pittsburgh Press, July 27, 1918; “American Giants Go Down to Defeat,” Pittsburgh Press, July 28, 1918.

41 Seamheads’ database, for the available statistics, suggests as much.

42 These counts do not include Seamheads’ data of games versus MLB teams in this span.

43 Again, per Seamheads.

44 “Pete Hill, Retired Baseball Player Visits Solider Son,” Chicago Defender, December 12, 1942.

45 Lester, Rube Foster in his Time, 105.

46 Cottrell, The Best Pitcher in Baseball: 133-134.

47 “Big Crowd Sees Detroit Stars Lick Maxwells,” Detroit Free Press, April 21, 1919.

48 “Jackson’s Best Tries to Halt Detroit Stars,” Detroit Free Press, May 25, 1919.

49 “15,000 Fans See American Giants Trim Detroiters,” Chicago Tribune, June 16, 1919; “Foster’s Giants Cop Again,” Chicago Tribune, June 18, 1919; “American Giants Beat Detroit, 8-5; Hurlers Wild,” Chicago Tribune, June 19, 1919; “American Giants Lost Final Battle to Detroiters, 5-4,” Chicago Tribune, June 20, 1919.

50 “American Giants Rally in Ninth to Annex First,” Detroit Free Press, July 27, 1919 ; “Whitworth is Master Over Blount’s Cast,” Detroit Free Press, July 28, 1919; “Stars Pummel Foster’s Club in Third Game,” Detroit Free Press, July 29, 1919; “Detroit Stars Tie Up Series with Chi Team,” Detroit Free Press, July 30, 1919; “Five Scores in Fifth Enough to Beat Chicagoans,” Detroit Free Press, July 31, 1919; “Detroit Stars Take Slugfest From Chi Team,” Detroit Free Press, August 1, 1919; “Detroit Stars Capture Final Game of Series,” Detroit Free Press, August 3, 1919.

51 For more on Mack Park, see Gary Ashwill, “Mack Park, 1929,” Agate Type, April 23, 2010, http://tinyurl.com/yymghtft.

52 “Stars Work Hard Scoring Odd Run on Doyle’s Boys,” Detroit Free Press, April 28, 1919.

53 “Champs Defeated by Colored Team in Good Battle,” Detroit Free Press, May 19, 1919.

54 “Second Battle Goes Same Way as Initial One,” Detroit Free Press, June 9, 1919.

55 “Stars Capture First in East,” Detroit Free Press, July 17, 1919.

56 For more on Hill’s 1919 season, see Gary Ashwill, “Pete Hill’s Historical Marker, Annotated,” Agate Type, March 18, 2011, https://tinyurl.com/y5h3vkd8.

57 Again, per Seamheads, with data from games versus MLB teams not included.

58 “Stars Take First from Cuban Team,” Detroit Free Press, May 16, 1920.

59 “Classy Pitching Wins For A.B.C.s,” Muncie Star Press, July 4, 1920.

60 “Blount and Hill Ready for Gong,” Chicago Defender, February 19, 1921.

61 “Monarchs in Second Place,” Kansas City Kansan, June 9, 1921.

62 “Charleston’s Hit is Winning Blow,” Detroit Free Press, July 6, 1921.

63 For more on the Royal Giants, see Gary Ashwill, “’Black Sox Players,’ Nos. 1 & 2” Agate Type, December 11, 2006, http://tinyurl.com/yyuvt53u; “19 Men Report to Chappie Johnson,” Philadelphia Evening Public Ledger, April 1, 1922; “Knights Down Chappie’s Men,” Schenectady Gazette, July 19, 1922; “North Phils to Oppose Fletcher,” Philadelphia Evening Public Ledger, July 31, 1922.

64 William Dismukes, “Winter’s Blast and Summer Echoes,” Pittsburgh Courier, November 24, 1923.

65 “Hilldale Played Only 59 League Games During 1923,” Chicago Defender, January 12, 1924.

66 “’Not Through as Player and Manager,’ Says Pete Hill,” Pittsburgh Courier, February 23, 1924.

67 For more on this rivalry, see Courtney Michelle Smith, Ed Bolden and Black Baseball in Philadelphia (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2017): 22-36.

68 “Holloway Better Jumper Than Frog, Hops to Baltimore,” Chicago Defender, April 24, 1924.

69 “Black Sox Take Lead in Eastern Colored League,” Baltimore Evening Sun, July 17, 1924; “Baltimore Black Sox Swamped by Hilldale,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 25, 1924.

70 “Clubs Forming East and West Remain Intact,” Baltimore Afro-American, December 20, 1924.

71 G.L. Mackey, “Sports Mirror,” Baltimore Afro-American, April 18, 1925.

72 “Sox and Giants to Lock Horns Sunday,” Baltimore Afro-American, August 8, 1925.

73 Ryan Whirty, “Remembering Pete Hill,” Hill’s Hall of Fame file.

74 “Easter Brands Bow to Colored Giants,” Buffalo Evening News, May 10, 1926; “County Champs Win, Fredonia (New York) Censor, July 7, 1926.

75 “Colored Elks to Travel,” Buffalo Evening News, June 25, 1927.

76 Just as the identification of Hill’s birthplace and year has a compelling story of historical research behind it, so does Jeremy Krock’s determination of his resting place. See Gary Ashwill, “Found: Pete Hill’s Grave,” Agate Type, November 8, 2010, https://tinyurl.com/yxu4p9q3.

77 “Power, Speed, Skill Make All-America Team Excel,” Pittsburgh Courier, April 19, 1952.

78 James A. Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues (Carroll and Graf, New York, 1994): 381.

Full Name

John Preston Hill

Born

October 12, 1882 at Buena, VA (US)

Died

December 19, 1951 at Buffalo, NY (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.