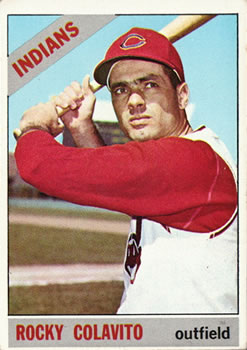

Rocky Colavito

On May 12, 1961, the Detroit Tigers were visiting New York to start a four-game series at Yankee Stadium. Although the season was only a month old, the Tigers held a two-and-a-half-game lead over the Yankees and were eager to send a message to the defending American League champions.

On May 12, 1961, the Detroit Tigers were visiting New York to start a four-game series at Yankee Stadium. Although the season was only a month old, the Tigers held a two-and-a-half-game lead over the Yankees and were eager to send a message to the defending American League champions.

As the eighth inning came to a close, Tigers left fielder Rocky Colavito returned to the third base dugout. Colavito, a native of the Bronx and a fan of the Yankees while growing up, always had a large rooting section whenever he returned home. As he neared the dugout, his custom was to look up at the stands to acknowledge his family and friends.

On this particular night, Colavito looked up at the stands and saw his father in a tussle with another fan. “I always look up there,” Colavito explained, “and when I saw my father struggling with somebody, I went right over the rail. My father is 60, and nobody is going to hit him while I’m there.” Colavito rocketed into the stands to come to his father’s defense, bowling over ticket holders as he went.

Detroit trainer Jack Homel led a posse of Detroit players to retrieve Colavito. “Some big son-of-a-gun got a hold of my back,” Colavito said of his uniform jersey. “But I shook him off fast. I wanted my hands free if there is [sic] going to be a fight.” The cause of the fracas was a Yankees fan, who had imbibed a few beers too many, annoying Rocky’s wife Carmen. Colavito’s older brother, Dominic, and his father Rocco, tried to intervene on Carmen’s behalf. “I found out,” said Colavito, “that some drunken bum was bothering my wife.” The “drunken bum” was escorted from Yankee Stadium by the police.

Umpire Ed Hurley immediately ejected Colavito from the field, citing a rule that any player who invades a fan area during a game must be ejected. After the umpires held a brief conference, it was decided that the other members of the Tigers would not face ejection for leaving the field of play. American League president Joe Cronin felt that the ejection was enough of a penalty for Colavito. “It wasn’t the right thing for the boy to go up into the stands,” said Cronin. “But I guess it was natural for him to want to help his father.”

Rocco Domenico Colavito was born August 10, 1933, in New York City’s Bronx borough. He was the youngest of five children (in order, Antoinette, Dominic, Vito and Michael) of Rocco and Angelina Colavito. Rocco the elder worked as an ice truck driver in the Bronx. Rocky attended Theodore Roosevelt High School, but dropped out after his sophomore year to play semipro baseball, hoping that would lead to a more direct route to his dream of playing major league baseball. “It was a big mistake”, Colavito recalled. “I didn’t want kids to say, ‘He dropped out of school and he made the big leagues.’” Baseball, though, prohibited a player from signing a professional contract until his class graduated. However, Commissioner Happy Chandler made an exception for Colavito, who had appealed the ruling, and Rocky was allowed to sign a contract at age 17.

After a tryout at Yankee Stadium, Cleveland scout Mike McNally was instantly taken with Colavito. “We had a tryout in the Bronx for about eight or ten kids,” said McNally. “I saw Rocky make a throw from the outfield. That was enough for me. I don’t think I have ever seen a stronger arm.” Colavito signed with the Indians for a $3,000 bonus and was assigned to Daytona Beach of the Class D Florida State League.

Colavito climbed the minor league ladder in the Indians organization, being promoted every year. In 1952 he split his time between two Class B teams, Cedar Rapids (Iowa) and Spartanburg (South Carolina). In 1953, Colavito was promoted to Reading (Pennsylvania) of the Class A Eastern League. While at Reading, two important people crossed Colavito’s path. The first was Carmen Perrotti, who lived in nearby Temple, Pennsylvania. After a year courtship, they were married in 1954. Rocky and Carmen each found work with the Indians during the offseason; Rocky worked in the public relations department while Carmen worked among the clerical staff at Cleveland Municipal Stadium. The other relationship was with pitcher Herb Score. Colavito and Score became roommates in Reading, and continued as roommates through their days in Cleveland. Their friendship remained until Score’s death.

When Colavito was growing up, his favorite team was his home-borough Yankees and his favorite player was Joe DiMaggio. Colavito even copied DiMaggio’s open batting stance to use as his own. He started to slump at Reading and manager Kerby Farrell had seen enough of the DiMaggio impersonation. “Rocky, we’ve gone far enough with you on this DiMaggio stuff. Let’s try to be Colavito,” the skipper said. Farrell worked with Colavito to improve his batting stance by having Rocky put his feet together and use a slight crouch in his batting stance. The changes had a positive effect on Colavito as he led the Eastern League with 28 home runs and 121 RBIs.

In 1954, Colavito and Score were both promoted to Indianapolis in the Class AAA American Association. Farrell joined his two stars in Indianapolis as manager. Colavito and Score both enjoyed tremendous years as Indianapolis took the league lead on April 22 and never relinquished it. For Score, he was named Minor League Player of the Year by The Sporting News after posting a 22-5 record with a 2.62 earned run average. Colavito smacked 38 home runs and drove in 116 RBIs. But Colavito showed off more than his power at the plate. He would routinely show off his strong right, arm by standing at home plate and throwing the ball past the outfield wall, more than 400 feet away.

Cleveland had a crowded outfield in 1955, with no less then ten players vying for employment. During the offseason, the Indians acquired Ralph Kiner from the Chicago Cubs. Kiner was at the end of a Hall of Fame career and occupied left field. Larry Doby, another future Hall of Famer, was in center field and Al Smith was in right field. Colavito was sent back to Indianapolis, where he hit 30 home runs and drove in 105, earning a late-season call up to the Indians. In the nightcap of a doubleheader in Detroit on September 24, Colavito subbed for Al Smith and went 4-for-4 with two runs scored in a 7-0 Cleveland win. In addition to his fine day at the plate, Colavito really had the fans at Briggs Stadium buzzing when in the fifth inning, Tigers first baseman Earl Torgeson was on second base and tried to advance on a deep fly off the bat of Detroit center fielder Bill Tuttle. Colavito caught the ball with his back to the wall and fired to third base to nail Torgeson. Not only was the throw from Colavito impressive, Torgeson was still about 30 feet from the bag when the ball arrived to Tribe third baseman Rudy Regalado.

As spring training began in Tucson, Arizona, in 1956, Colavito was feeling more confident about sticking with the varsity. The competition for outfield positions was sliced some, and Rocky had nothing more to prove at the minor league level. However, in the first couple of months, Colavito found the going rough, hitting .215 with five home runs after 93 at-bats in 37 games. On June 16, Colavito was optioned to San Diego of the Pacific Coast League to make room for Gene Woodling, who had been on the disabled list for 30 days with dizzy spells.

Colavito’s wife was expecting their first child, and he was concerned about leaving and going across the country. General Manger Hank Greenberg promised Colavito that it would only be for three weeks. After battering Pacific Coast League pitching to the tune of 12 home runs and a .368 batting average, Colavito returned to the Indians. Colavito credited his hitting success at San Diego to work he had put in with Tribe manager Al Lopez. Lopez changed the rookie’s batting stance from a closed one in a crouch to a closed stand-up position. To make room for him, the popular Dale Mitchell was sold to Brooklyn.

The rest of the season Colavito continued to hit well, batting .301 with 16 home runs and 48 RBIs. The Indians, with three 20 game winners on their staff (Score, Early Wynn and Bob Lemon) finished in second place in the American League for the second straight year, nine games behind New York.

One major change in Cleveland was the resignation of Lopez, who, in six years at the helm, guided the Tribe to one first-place finish and five second-place finishes, felt under appreciated by Greenberg. Although the Indians were competitive on the field, at the box office they drew the second lowest attendance in the American League. Kerby Farrell was promoted from Indianapolis to replace Lopez, who ended up on Chicago’s south side as the new skipper of the White Sox.

Tragedy struck Cleveland on May 7, 1957, when pitcher Herb Score was hit in the right eye off the bat of the Yankees’ Gil McDougald in the first inning. Score suffered a tear to the retina of his right eye and was lost for the season. For Colavito, he played right field most of the season and led all right fielders in putouts with 266. He also had 12 assists. At the plate, Colavito saw his batting average drop by 24 points from the previous season to .252. Yet, he still drove in 84 runs and finished second on the team, to Vic Wertz, with 25 home runs. Cleveland finished in sixth place, 21 1/2 games behind the Yankees. It was their worst finish since 1946.

After the season, GM Greenberg was relieved of his post. That November, Frank “Trader” Lane was given the reins of the Cleveland franchise. He earned the nickname for making more than 400 trades in his career as general manager of the Cardinals, White Sox, Indians, and Athletics. Nobody was above being traded when Lane was in charge. From the Cleveland team that ended the 1957 season to the opening day roster of 1960, only two players, catcher Russ Nixon and infielder George Strickland, were the only holdovers. (Nixon was traded in March 1960 to Boston, but the trade was voided when catcher Sammy White refused to report to Cleveland. Nixon was traded to the Red Sox for good in June 1960.)

Lane hired Bobby Bragan to replace Farrell and lead the Indians in 1958. Bragan had managed In Pittsburgh in 1956 and part of 1957, guiding the Pirates with a winning percentage of .390 over 261 games played. Rocky believed that his uniform number, 38, was more suited for a rookie. He requested and was granted a change to number 6. Some believed Rocky made the switch because 6 was closer to that of the number worn by his idol Joe DiMaggio, who wore number 5. Colavito played some first base to spell the aging Mickey Vernon, but also was splitting some time in right field with Roger Maris. Rocky had appealed to Bragan, promising him that he would slug 35 home runs if he was given the chance to be in the everyday lineup. Colavito became the every day right fielder when Lane traded Maris to Kansas City on June 15, 1958. Colavito made good on his promise, clouting 41 home runs and driving in 113 runs with a .303 average. Colavito added 14 assists from right field and led all outfielders with six double plays made. He finished third in the Most Valuable Player voting behind Jackie Jensen of Boston and Bob Turley of New York, garnering four first place votes.

Bragan wasn’t there to see it. He was replaced after 67 (won-lost record 31-36) games by Lane with former Indian Joe Gordon. The popular second baseman, who was a key member of the Indians’ 1948 world championship team, Gordon had been managing in the minor leagues. He ended the campaign with a 46-40 mark and the Indians had reason for optimism heading into the 1959 season. Gordon did install Colavito as a relief pitcher on August 13, 1958, in a home game against Detroit. In the second game of a doubleheader, Colavito relieved Hoyt Wilhelm in the top of the seventh inning and pitched three innings of no-hit ball against the Tigers. Colavito struck out one batter, and walked three.

The Indians started 1959 in fine fashion, winning their first six games, and 10 of 11 to start the season. As the schedule concluded on May 31, Cleveland held a one-game lead over the White Sox. The pitching rotation, led by Cal McLish, Gary Bell, and rookie Jim Perry, was leading the way from the hill.

The Sporting News had written an article in its June 10 edition touting Colavito as the American League slugger most likely to break Babe Ruth‘s record of 60 home runs in a season. Eddie Mathews of the Milwaukee Braves was the choice to break the record in the National League. “Don’t be silly,” Colavito laughed it off when the suggestion was made to him. “That was a fine compliment The Sporting News paid me,” observed Colavito. “I hope my slump is not letting the paper down.”

Colavito broke out of his slump when on June 10 he hit four consecutive home runs in Baltimore. Colavito was 4-for-4 on the day with one walk, six RBIs and five runs scored. “Honest, I was just trying to meet the ball,” said Colavito. “No, I wasn’t going for a fourth. I thought I had a pretty good night already, hitting three.”

Colavito was selected to start in his first All Star Game, July 7, 1959, at Forbes Field. Colavito went one for three, singling off Lew Burdette in the fourth inning. Colavito graced the cover of Time with the headline “BASEBALL: Here Come the Kids.” The article focused on the majors’ up-and-coming stars. The article centered on Colavito, but also included capsules on Vada Pinson, Maris, Luis Aparicio, Willie McCovey, Harmon Killebrew and others.

As far as the pennant race was concerned, the Al Lopez-led Chicago White Sox had raced past the Indians to lead by 4 1/2-game lead on August 18. The Indians sliced their lead to 1 games when the White Sox came to Cleveland for a four-game weekend series in late August. More than 165,000 disappointed fans turned out for the series in Cleveland as the White Sox won all four games and seven of their next ten to pull away from Cleveland. Colavito had a forgettable series, going 2-for-15 with a home run in the last game. The month of September did not get any better for Colavito as he hit three home runs, knocked in 13, and batted.207. For the season, Colavito hit 42 home rums, tying Harmon Killebrew of Washington for the AL home run crown. Colavito also drove in 111 runs, one RBI shy of Boston’s Jackie Jensen, who led the league with 112 RBIs. His batting average fell 46 points off the previous year, down to .257.

General manager Frank Lane loved to talk trades, throwing names around as if he were dealing baseball cards instead of people. When he was in charge in St. Louis, he even tried to trade Stan Musial. As Musial was an icon to Cardinals fans, Colavito was an icon to Tribe fans. Boys emulated him in the sandlots, either copying his batting stance or the way he flexed his bat behind his back. Girls doted on him, starting numerous fan clubs. Parents loved him as a role model for their children. Most fans appreciated his work ethic, home run power and strong, right arm. Colavito had charisma, and even though he was from the Bronx, Cleveland fans felt that he was one of their own. “Don’t Knock the Rock” was the mantra of many fans, young and old alike.

Lane had always coveted Harvey Kuenn of Detroit. To Lane, the long ball was overrated, and he favored the contact hitter. On April 17, 1960, Colavito was sent to Detroit for Kuenn. Cleveland fans were in an uproar over the trade. Lane traded 1959’s home run king for 1959’s batting champion. Cleveland Manager Joe Gordon gave the trade his full endorsement. “Actually, both Joe and I agree that the home run is overrated,” Lane pointed out. “Look at the Washington club last year. They almost led the league in home runs and finished last.” Lane went on to say that even though Colavito was very popular in Cleveland, and that people came to the park to see Rocky hit home runs, doubles and singles won just as many games. “Kuenn is an all-around player,” said Gordon. “He can run, he can throw, he can shag a fly ball and he’s probably the toughest hitter in the league. I’m glad we got him.”

The Indians were playing the White Sox in Memphis, Tennessee, in their last exhibition game, when the deal was sealed. In the fourth inning, Colavito was standing on first base as the result of a force out. Gordon came out to Colavito at first base, shook his hand and informed him that he had been traded to Detroit for Kuenn. Colavito said that Gordon spread the tale that after Colavito was told of the trade, he asked Gordon “Kuenn and who else?” “It was the biggest lie ever,” said Colavito. “It implied that I didn’t think Harvey was good enough to be traded for me. That wasn’t it at all. I just couldn’t believe they did it. It caught me totally by surprise. I had heard one rumor in spring training, but that had died down. But I never said anything negative about Harvey Kuenn. After that, I never had any stomach for Gordon or Lane.”

The Cleveland Plain Dealer fielded hundreds of phone calls at their switchboard and a ratio of 9-1 fans was opposed to the trade. Reaction to the trade ranged from “My teeth nearly fell out” to “I’ll never go to the ballpark again”. Eighth grader Carol Kickel may have captured the feeling of Tribe fans better then anyone when she said “I just want to tell you this: I belong to one of the Rocky Colavito fan clubs. It’s all over. We’re going to start a new one, the ‘Lane Haters’”

In Detroit, fans and media were overjoyed at the acquisition of Colavito. “The Tigers lost 30 games by one run last season due to the lack of a long ball hitter,” said Edgar Hayes, sports editor of the Detroit Times. “This deal strengthens the Tigers, weakens the Indians. Colavito hit eight home runs in spring training this year, while the entire Detroit club has hit only 14.”

Or as Cincinnati general manager Gabe Paul put it, “The Indians traded a slow guy with power for a slow guy with no power.”

The next day, Colavito’s roommate, Herb Score, was dealt to the White Sox for pitcher Barry Latman. Score never returned to his pre-injury form, but to his credit, he never used it as an excuse. Score was only too happy to be reunited with Al Lopez to try and rejuvenate his career.

As luck would have it, Detroit was opening the 1960 season in Cleveland. Colavito struck out four times against his former team, going hitless in six at bats. The next day, Colavito hit a home run and drove in three runs as Detroit swept the two game series.

In another trade between Detroit and Cleveland, the Indians swapped first baseman Norm Cash for infielder Steve Demeter. The Indians had acquired Cash from Chicago in the off season, and dealt him on April 12 to Detroit, five days before the Colavito-Kuenn deal. Demeter played all of four games for Cleveland in 1960 and then would be out of baseball. Together, Colavito and Cash were teammates in Detroit for four years, combining to smack 263 home runs and 793 RBIs.

Frank Lane was not quite done making deals with Detroit. Lane and Detroit GM Bill DeWitt traded managers on August 3, 1960. Gordon went to Detroit and Jimmie Dykes took over the helm in Cleveland. It was a curious move for the Indians, who were in fourth place, yet just six games off the pace. The unusual swap of field managers did not help either team as both teams trailed by more then 20 games out of first place at season’s end.

For Colavito, 1960 would be a roller coaster year. He started slowly, and was benched by Dykes for a time. But Colavito finished fast, hitting 31 home runs and collecting 75 RBIs in the last four months of the year.

Joe Gordon was released from his contract by Detroit so that he could take the managerial position in Kansas City in 1961. Bob Scheffing replaced Gordon and promptly moved Colavito to left field. “He’ll have all spring to get used to left field,” said Rick Ferrell, the Tigers’ vice president. “He’ll do a god job there. The left fielder has only one long throw-to home plate. It gives a fellow less to think about out there. They won’t get a cheap run against us. Colavito will fire the ball from left field.” The move to left field paid immediate dividends as Colavito led all left fielders with 14 assists and 301 putouts.

The Tigers and Yankees battled for the AL flag for most of the 1961 season. Colavito had a monster year, hitting 45 home runs, driving in 140 runs, scoring 129 runs and hitting .290. A wonderful year for sure, but in every category except for batting average, he was outdone by the Yankees’ Roger Maris, his former teammate in Cleveland. Maris went long for 61 home runs, 141 RBIs and 132 runs scored. The Tigers would also finish second to New York by eight games. Colavito was honored by The Sporting News on its AL All-Star team.

Colavito struggled at the beginning of 1962, when he did not connect on a home run in his first 100 at bats. He finally broke through, getting a solo shot off of Minnesota’s Camilo Pascual on May 16, at Tiger Stadium. From that point on, the Rock was solid. In the month of June, Colavito batted, 356, collected 42 hits, 24 RBIs and eight home runs. Included in his hot streak was a game on June 24 in Detroit. The Tigers lost in a 22 inning marathon to the Yankees, 9-7. Both teams combined to use 14 pitchers. Colavito went 7-for-10 at the plate, stroking six singles and adding a triple. He was selected to play the 1962 All-Star Game at Wrigley Field. Colavito hit a three-run homer in the seventh inning off Turk Farrell. For the regular season, Colavito finished with 37 homers, 112 RBIs and a .273 batting average. Defensively, he led all left fielders with 359 putouts.

The 1963 season was his worst offensively during the four years that he played in Detroit. Through April and May, Colavito hit four round trippers and 14 RBIs. He picked it up some as the season went on, and finished the season with 22 home runs and 91 RBIs; just two of those blasts came in September. Detroit as a team had a miserable year, tying the Indians for fifth place, 251/2 games behind New York. Scheffing had been replaced as manager after starting the season with a 24-36 record. He was replaced by Chuck Dressen.

Colavito was dealt to Kansas City that November 18 in a five player deal. The main player the Athletics gave up was second baseman Jerry Lumpe. Feeling unappreciated in Detroit, Colavito was happy to find a new home. Kansas City also dealt for first baseman Jim Gentile from the Orioles to from a formidable one-two punch in the middle of their lineup. Gentile had averaged 31 home runs a season the four years he played in Baltimore. Colavito was chosen to play in 1964’s Mid-Summer Classic at Shea Stadium on July 7. Again he victimized Turk Farrell with a double in the seventh inning.

The Rock reached two milestones with one swing of the bat by collecting his 300th home run and 900th RBI on September 11, 1964, in Baltimore. With one out in the first inning, shortstop Wayne Causey doubled and scored on Colavito’s 32nd home run of the season. Kansas City owner Charles Finley had a Brinks truck parked outside Municipal Stadium in Kansas City to celebrate Colavito’s feat. The truck contained 300 silver dollars that were to be presented to Colavito once he hit number 300. Unfortunately, he hit the milestone homer on the road.

Colavito had one of his finest offensive years of his career in 1964. Rocky smacked 34 home runs, drove in 102 runs, and collected 31 doubles and 83 walks while batting .274. Gentile, who hit 28 homers, credited Colavito with his own fine season. “Rocky told me to cut down on my swing, shorten my stance and forget my spring training troubles,” said Gentile. As a team, Kansas City finished in last place of the American League, 42 games behind first-place New York.

Cleveland reacquired Colavito as part of a three-team swap January 20, 1965. Athletics general manger Pat Friday said it was with great reluctance that Colavito was dealt. “He is a great player and he was a favorite with the fans here,” Friday said of Colavito. “I never have known a player who hustled as consistently and as much as Colavito.” Cleveland sent pitcher Tommy John, outfielder Tommie Agee and catcher John Romano to Chicago. Cleveland also received catcher Cam Carreon from Chicago. John won 286 games in his career after leaving Cleveland, mostly with the Dodgers and Yankees. Agee won AL Rookie of the Year honors in 1966. He also proved to be a key player on the New York Mets’ 1969 world championship team.

Cleveland general manager Gabe Paul said he had tried to right the wrong made by Lane five years earlier. “I made more then 100 offers to Detroit when Colavito was there.” Cleveland fans flooded the switchboards of the Indians and the local newspapers, complimenting Paul on a shrewd deal. “I’m glad to be going home-and I do mean home,” said Colavito. “Every year when I went into Cleveland with the Tigers or Athletics, I would say to myself, ‘Wouldn’t it be nice to be playing here again?’”

Birdie Tebbetts was in charge for the Tribe in 1965. The crowd of more than 44,000 was the largest opening day gate in the major leagues in 1965. With the hometown fans cheering wildly that their favorite star had come back to them, Colavito did not disappoint. He slugged a two run homer off California Angels reliever Fred Newman. Besides Colavito, the Indians were counting on home run production from Leon Wagner. Colavito, Wagner and first baseman Fred Whitfield combined for 80 home runs and 277 RBIs. Colavito led the AL with 108 RBIs and 93 walks, and was the AL’s starting right fielder in the 1965 All Star Game. Colavito played errorless defense in right field all season, handling 274 chances. He reached the 1,000-RBI plateau on September 6, 1965, in the second game of a doubleheader in Washington. Colavito was voted the Indians’ Man of the Year by the Cleveland chapter of the Baseball Writers Association of America.

Colavito clobbered 30 home runs for the Indians in 1966, but his batting average dropped to a career low of .238. Colavito, who played with a sore shoulder for much of the season, set a record for playing in 206 games without committing an error. Tebbetts resigned on August 19 and was replaced by George Strickland. Strickland had some previous managerial experience. He filled in for Tebbetts as manager in the first half of 1964 when Tebbetts had suffered a heart attack. Strickland benched Colavito for his poor showing during the last month of the season. “I don’t like it and I don’t mind saying so,” said Colavito. “What really burns me is that I played all year with a sore shoulder and always tried to do my best. Now, with 12 games left, he is going to rest me.”

Rocky was a holdout at the beginning of spring training in 1967. Although the exact figure of his 1966 contract was not known, it was believed to be in the $70,000 range. Gabe Paul asked Colavito to take a 25 percent pay cut, the highest percentage that was allowed to be taken by a player. Colavito balked and held out until March 7, when Paul and Colavito came to an understanding. “I’m not happy about the cut,” said Colavito. “No conscientious player ever is. Gabe gave in some and so did I. I hope to have a big year and win the cut back.”

Former Milwaukee Brave Joe Adcock became the new manager in 1967. Adcock, who had no previous managerial or coaching experience at any level, moved Colavito to left field and instituted a platoon situation with Wagner. The circumstances made both players extremely unhappy. “Yes, “I’m unhappy,” said Wagner. “I should be playing regularly. I’m 32, not 36, and I’ve got at least four more good years ahead of me. They gotta prove to me it’s going to work. Any team that’s good enough to platoon me and Rocky ought to be good enough to win the pennant.”

Colavito had similar thoughts. “I’m tired of this platooning and I waited a long time before saying anything,” said the Rock. “I’m not a trouble maker, never was and never will be, but I feel I must speak out now and say what’s inside me.” Earlier in the year in a game in Boston, Colavito was lifted for Wagner when the Red Sox brought in a righthander with the bases loaded. Colavito and Adcock became embroiled in a heated argument in the dugout. Two days later an article appeared in the Cleveland Press titled “Join the Team, Rocky”. The article accused Colavito of not being a team player and putting personal feelings ahead of the team’s success. The article spoke specifically about his holdout over his salary debate with Paul, putting money demands over the team.

After only appearing in 63 games for the Indians, Colavito was traded to the White Sox on July 29, 1967, for outfielder Jim King. The Cleveland Plain Dealer had been running a “Favorite Indian Contest”. Rocky was in the lead at the time of the trade. “Max [Alvis] will probably win the most popular Indian contest by default with Rocky gone,” mused catcher Duke Sims.

Colavito believed that Paul and Adcock were both working in concert against him so that he could not recoup his lost salary by meeting incentives on the field. The Cleveland brass insisted there were no problems. “It’s simply that he was not helping us and it’s obvious our outfield needs some reconstruction and rehabilitation. That’s all.” said Paul.

Chicago had a two-game lead over Boston in the American League. Two days after the trade, Chicago was in Cleveland, and Colavito hit a two-run home run off Luis Tiant in the tenth inning that would prove to be the winning margin of a 4-2 Sox victory.

The White Sox posted a 31-30 record in August and September, while Boston went 35-26 to win the pennant in 1967, with Chicago finishing three games back and in fourth place. For Colavito, he would appear in 60 games, hitting 3 home runs and 29 RBIs.

Toward the end of spring training in 1968, Colavito was sold to the Los Angeles Dodgers. The Dodgers wanted an insurance policy against left-handed pitching and Colavito was available. He hit three home runs for the Dodgers, all of them coming in a two game series at Wrigley Field in Chicago.

Colavito was released by the Dodgers and signed with the Yankees on July 15. In his first appearance wearing the pinstripes for his hometown team, Colavito blasted a three run homer in he fifth inning off of the Senators’ Joe Coleman, helping the Yankees to a 4-0 home win.

The highlight for Colavito came on August 25 when manager Ralph Houk beckoned him from the bullpen to relieve starter Steve Barber in the fourth inning. Pitching two and two-thirds innings of one-hit ball, Colavito picked up the victory for the Yankees. He was the last non-pitcher to win a game until catcher Brent Mayne of Colorado equaled the feat on August 22, 2000. Colavito walked two and struck out one. “When I got in the game, I threw mostly fastballs. A few curves and some sliders,” said Colavito. “My slider worked better in the bullpen than on the mound, but it was there.”

Colavito retired after the season. He returned to Cleveland to work as a TV analyst for WJW in 1972, 1975 and 1976. Rocky also served on the Indians’ coaching staff in 1973 and 1976-1978. Colavito later served on Tribe teammate Dick Howser‘s coaching staff in 1982 and 1983 when Howser managed the Kansas City Royals. Rocky also helped his father-in-law run his mushroom farm near Reading, Pennsylvania.

In 1994, Cleveland sportswriter Terry Pluto wrote a bestselling book entitled The Curse of Rocky Colavito. In it, Pluto details the trials and tribulations of the Cleveland franchise after Frank Lane traded Colavito to Detroit. Pluto, who was born in 1955, recalls that the first words he may have learned were “Don’t Knock the Rock”. He picked up the phrase from his father when he was quite young, as did most Tribe fans of that generation. Pluto describes the Cleveland fans’ admiration for Colavito thus: “He was everything a ballplayer should be: dark, handsome eyes, and a raw-boned build-and he hit home runs at a remarkable rate.”

In 2001, as a celebration of their 100-year anniversary, the Cleveland Indians named their 100 greatest players of all time. The players were selected by a panel of veteran baseball writers, executives and historians. Rocky was selected as one of 23 outfielders to the all-time team.

As of 2024, Colavito remained among Cleveland’s career leaders in many categories, with his 374 home runs as a right-handed hitter and his 268 four-baggers as a right fielder, and one-game mark of 16 total bases. He also shared all-time single-season marks for best fielding average by an outfielder (1.000) and fewest errors by an outfielder (0), both set in 1965.

On August 10, 2021, Colavito’s 88th birthday, a statue in Colavito’s likeness was unveiled in the Little Italy section of Cleveland.

Rocky and Carmen lived in Bernville, Pennsylvania. They had three children, Rocky Jr., Marisa and Steven. Rocky enjoyed hunting and denied that he ever put a curse on the Cleveland Indians.

Rocky Colavito died at the age of 91 on December 10, 2024.

Sources

Publications

Pluto, Terry. The Curse of Rocky Colavito. Simon and Schuster, 1994.

Spatz, Lyle (ed). The SABR Baseball List and Record Book. Scribner, 2007.

Articles

Cleveland Press, various articles between 1955-1960 and 1965-1968.

Detroit Times, various articles in 1960.

New York Times, various articles between 1961-1968.

Plain Dealer (Cleveland), various articles between 1955-1960 and1965-1968.

The Sporting News, various articles between 1955 and 1968.

Time, August 24, 1959.

Website

http://cleveland.indians.mlb.com/index.jsp?c_id=cle

http://minors.sabrwebs.com/cgi-bin/milb.php

http://retrosheet.org/newslt16.htm

http://www.baseball-reference.com/

http://www.time.com/time/

https://www.bostonglobe.com

Other Sources

1930 United States Census

Picture Credit

The Topps Company

Full Name

Rocco Domenico Colavito

Born

August 10, 1933 at New York, NY (USA)

Died

December 10, 2024 at Bernville, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.