Gene Brabender

It would have been fun to see Gene Brabender wrestle with Frank Howard: “a polar bear versus a grizzly,” suggested his old teammate, Jim Bouton. At 6 feet, 5 1/2 inches and 225 to 240 pounds, “Bender” gave away roughly two inches and 30-40 pounds to “Hondo.” Yet the big man from Black Earth, Wisconsin, ranked right with the Senators slugger as the strongest big-leaguers of their day — perhaps ever. Amid the motley cast of the 1969 Seattle Pilots, the “hard-throwing righthanded country boy” [1] gave Bouton much to write about in his classic diary Ball Four:

It would have been fun to see Gene Brabender wrestle with Frank Howard: “a polar bear versus a grizzly,” suggested his old teammate, Jim Bouton. At 6 feet, 5 1/2 inches and 225 to 240 pounds, “Bender” gave away roughly two inches and 30-40 pounds to “Hondo.” Yet the big man from Black Earth, Wisconsin, ranked right with the Senators slugger as the strongest big-leaguers of their day — perhaps ever. Amid the motley cast of the 1969 Seattle Pilots, the “hard-throwing righthanded country boy” [1] gave Bouton much to write about in his classic diary Ball Four:

“We were talking about what to call Brabender when he gets here. He looks rather like Lurch of the ‘Addams Family,’ so we thought we might call him that, or Monster, or Animal, which is what they called him in Baltimore last year. Then Larry Haney told us how Brabender used to take those thick metal spikes that are used to hold the bases down and bend them in his bare hands. ‘In that case,’ said Gary Bell, ‘we better call him Sir.’” [2]

The pitcher stood out visually and audibly, with his large frame, Clark Kent glasses, and stentorian voice. He had an outsized personality to match: hearty and jovial, garrulous and guileless. “He was a big easygoing guy who gave me a lot of laughs,” says his teammate with the Baltimore Orioles, Hall of Fame third baseman Brooks Robinson. Sportswriters, who played up Gene’s occasional comic mishaps, loved him; he also loved silly clubhouse pranks. Still, Brabender had a serious side — he was more than a caricature. As a rookie, he contributed to a World Series champion, the 1966 Orioles. His 13 wins with the Pilots also set a mark for expansion teams that lasted until 1998. Shoulder problems ended Gene’s big-league career before he was 30, though, and he also passed away at the young age of 55.

Eugene Mathew Brabender was born on August 16, 1941, in Madison, Wisconsin. This German family name (pronounced BRAH-bender) is fairly common in the Badger State, especially in Dane County, which turns to picturesque farm country as one travels west of the state capital. The Black Earth valley — once home to the Winnebago Indians, whose mounds still dot the area — received its first European settlers in 1842-43. A little village sprang up in 1850, and it took the name of its rich soil in 1857.

Gene’s father, Bernard Brabender, worked for the Gisholt Machine Company of Madison when his wife Cecilia (née Meier) gave birth to their second child. When the U.S. entered World War II, Bernard went into the Army. He got hurt in basic training, though, and wound up guarding prisoners of war in Tampa, Florida. Since he spoke German, he became friends with many of the Deutschlanders.

After the war, Gisholt was going to give Bernard a promotion, but he had never admitted something when he was first employed — he lacked an eighth-grade education. “They had never asked before, but then they wanted to see his diploma, and so Dad thought the only thing he could do was farm,” remembered Gene’s older sister, Caryl. The boy was about six years old when his family moved to Black Earth, where Cecilia’s father had owned a 400-acre farm but lost it during the Depression. The Brabenders rented the old Meier property and repurchased it several years later, in the early 1950s.

There were seven Brabender siblings. Gene’s brothers, Darrell and Deane, were roughly five and eight years his junior. Then came twin sisters, Charyl and Charlene, plus one more girl named Karyn. It was a typical farm childhood, with plenty of hard work and chores. Starting with the freshly painted white picket fence, all hands kept the entire spread neat as a pin. There may not have been much money, but there was plenty to eat — the good earth provided.

The boys rose at around 4:30 AM. They milked 40 or so producing cows by hand and poured the buckets into old-style milk cans. Then they carried the cans the length of the 54-stanchion dairy barn, putting them in the cooler for the milkman to pick up. “No pipelines,” notes Deane. “Except for the tractor, and some horses, we did everything by hand.” The draft horses pulled logs away after Bernard, Grandpa Meier, and Gene cleared woodland. Darrell remembers that timber rattlers nested in the groves. His big brother seized the snakes by the tail, swung them like a lasso, and (before they became a protected species) dispatched them with a whip-crack.

There were also about 200 hogs and several thousand chickens. The girls’ tasks included cleaning and grading pails of eggs, as well as gardening and canning. The garden was no mere patch, rather a full acre with varied produce that needed constant weeding and tending. The one day of rest was Sunday; the strict Catholic family never missed Mass.

Still, the youngsters had fun too. “Gene was always a happy kid. We didn’t have Little League, but he was always practicing with a baseball,” said Caryl. “He kept breaking holes in the barn door!” added Deane. “He had a piece of tin for a strike zone and he kept moving it around. Dad got sick of patching that door and finally he set up a tire with some chicken wire behind it for Gene to throw at.”

The Catholic Youth Organization provided about the only baseball leagues for children in the area. Back then, though, not everything had to be structured. “We just played ball!” said Darrell, who also remembered how the Brabenders followed the Milwaukee Braves, with Hank Aaron, Eddie Mathews, Warren Spahn, and Lew Burdette. “When they pulled up stakes, we were pretty burnt up — it was a sore spot.” On one visit to County Stadium, Gene predicted to his father, “I’ll play here someday.”

Through eighth grade, Gene attended St. Francis Xavier parochial school in nearby Cross Plains. Organized team sports became part of his life year-round at Black Earth High School. In 1960, when he graduated, the town’s population was around 800. He would later boast that he knew them all by first name. In 1966, he noted, “There were 26 in my graduating class, including eight girls. We barely had 11 big guys for the football team [in fact, they had to play eight-on-eight against even smaller towns]. All the subs were midgets.” [3]

The Brabender men were all big and strong, but Gene had unusual size and athletic skill. In the fall, he was a defensive tackle and running back. Knees churning, he dragged undersized linebackers 15 yards downfield. As a punter and kicker, his booming leg got him attention from college recruiters. During the winter he also earned first-team Tri-County honors in basketball as a center. (He continued to play hoops with the Black Earth amateur team during his first two off-seasons in pro baseball.) In the spring the powerful youth went out for track and field. Sure enough, his main event was shot-put. Deane remembered, “It was like picking rocks in our fields, or our hay bales. Gene would stand up on a wagon and throw ’em up over a beam into the loft.”

Brabender’s first love, though, was baseball. He actually didn’t start to pitch in high school until his senior year; previously he played first base and outfield. He remembered that as a senior, “Heck, it wasn’t anything for me to start a game as the pitcher and wind up as the catcher.” He hit .440 as a junior and .444 as a senior. Later, when he got to the majors (where he hit .102 lifetime), Gene chuckled, “These fellows are pretty smart, they don’t throw all fastballs.” [4]

He gained experience playing in Wisconsin’s Home Talent amateur league. As the Black Earth Chamber of Commerce web site notes, “Home Talent baseball has had a home in this community since the inception of the organization,” founded in 1929. “Really fast and really wild,” Gene won a reputation as the scariest hurler in the region. During the summer of 1960, “Black Earth invited Waunakee to play a night game at Black Earth. Waunakee’s brass, watching Brabender in the all-star game, also played at night, had a unanimous opinion: ‘that guy’s not for us under those lights.’” [5]

In fact, remembered his friend Steve Schmitt, Gene once broke an opponent’s jaw in a Home Talent game with a pitch that got away. He broke down and said he would never pitch again before the batter got up, put his arm around Gene, and consoled him.

Major-league scouts took notice of the young fireballer, thanks to Black Earth High coach Don Oscar, who sent letters to all 16 teams alerting them. Oscar remembered that Cincinnati and Washington sent bird dogs around, but the Los Angeles Dodgers had the inside track. “Upon graduation, Brabender was offered a chance to pitch batting practice with St. Paul of the Triple A International League [sic; the Dodgers affiliate was in the American Association]. The try-out lasted five days, and he was signed for a $10,000 bonus by the Dodgers.” [6]

St. Paul coach Carroll Beringer noted that he was pressed back into service as an active pitcher early in 1960, so he didn’t run that tryout or recommend Gene. Beringer’s longtime colleague, future Phillies manager Danny Ozark, was the Saints’ skipper that year. Ozark couldn’t remember exactly who the scout was either, but he later managed Brabender in Instructional League. “I remember him. I named him ‘Brew.’ He was a tall rugged man with a good sinking fastball.” However, Baltimore sportswriter Gordon Beard’s account of the 1966 champion Orioles, Birds on the Wing, names Jerry Flathman as the scout. Records also show that St. Paul business manager Mel Jones had a hand in the signing.

Connie Grob, a minor-league pitcher from Cross Plains, was a friendly adviser to the Brabenders. For the past few years, Connie (who was with the Washington Senators in 1956) had played for Spokane and Montreal, two other Triple-A teams in L.A.’s chain. He thought Gene could get more money, but the young man was happy with his opportunity.

As a result, Gene quit college. In September 1960, the same month he signed, Brabender had started at Whitewater State College (now the University of Wisconsin-Whitewater). He intended to obtain a teaching degree; he also had a minor in music, which he was able to read. Overall, though, the money and the game proved the stronger lure. Gene stayed for just one semester, through January 27, and so he never played baseball at the NCAA level.

The hulking 19-year-old left Black Earth in March 1961 for spring training at Dodgertown in Vero Beach, Florida. [8] The following month, he headed west for Great Falls, Montana in the Pioneer League (Class C). After posting a record of 2-3 with a 6.33 ERA in his first 8 games as a pro, Brabender took a step back to Class D. With Orlando in the Florida State League, he went 4-10, 5.01 in 20 games. Control was his major issue: while he struck out 100 batters, he walked 119 in 115 total innings.

Brabender remained in the Florida State League in 1962, though the Dodgers affiliate had moved to St. Petersburg. His record was 9-14, while his ERA improved to 3.20. He fanned 204 men in 191 innings but was still very wild, walking 139 and unleashing 37 wild pitches. That fall, the Dodgers sent Gene to the Instructional League in Arizona.

In 1963, with Salem, Oregon (Class A), the young hurler showed even greater promise. Gene went 15-10 with a 3.30 ERA and led the Northwest League with 223 strikeouts, though he still walked 108. His 16 complete games also topped the league; during one midsummer stretch, he fired five shutouts in seven games. It was all or nothing with Brabender that year, though, as he averaged only three innings in his other 15 appearances.

Still, the good far outweighed the bad. Gene was promoted to Albuquerque in the Double-A Texas League, making five relief appearances (1-0) and notching 8 more Ks in 4 innings. He remained impressive in the Arizona Instructional League, striking out 38 in 33 frames with a 2-0 record and 1.64 ERA. Recalled future Angels manager Lefty Phillips in 1971, “After one game, I saw him pick up the Iron Mike pitching machine and carry it to the clubhouse. Those things have to weigh several hundred pounds and I gave him hell for lifting it.” [9]

Deane Brabender told a couple of anecdotes about how his brother struck fear in minor-league hitters. “He wore those thick glasses, and one game it was so hot and he was sweating so much that he threw away the glasses because he couldn’t see. The batter stepped out. The umpire ordered him back in, and the guy said, ‘Not until he puts them glasses back on!’

“Another time a batter came to the plate with one of those coal miner’s lamps on his head. The ump said, ‘What’s the matter, can’t you see?’ The batter said, ‘It’s not for me, it’s for him!’”

At a crucial juncture, Gene’s career was interrupted as he spent the 1964 and 1965 seasons in the Army. “He got drafted,” sister Caryl recalled. “Our parents were really upset — nobody else had to go two years.” Unsurprisingly, he was made a military policeman. He was stationed at Fort Leonard Wood in Missouri to begin with, but received a furlough to marry Karen Gean Zespy of Beloit and Black Earth on May 1, 1964. The newlyweds then moved to the MP’s new post, Aberdeen Proving Ground (APG) in northeastern Maryland. [10]

Brabender carried the APG Bombers both years. In 1964, even though he struck out almost two batters per inning on average, he still went just 9-7 (the team was 12-11). Run support was slim in several losses, but there was a bigger problem — after the team’s one experienced catcher transferred out, nobody else could hold him. He burned through four other receivers with bruised, jammed, and broken fingers. Passed balls abounded — 27 in the first game of the Second Army championship! Even so, Gene’s highlights included a 24-strikeout no-hitter on August 13, after a sleepless night awaiting the birth of his son Kenny. Other outings featured 22 and 19 Ks (the last in a 1-0 loss). He also clubbed 10 homers and hit .371.

Gene had a sore arm and was rocked a couple of times early in APG’s 1965 season. Still, the occasional right fielder remained a heavy hitter and rebounded to post a 10-5 record for the 18-12 Bombers. From a new mound dubbed “Brabender Peak,” he fired another no-hitter on June 17. The 15-K performance was marred only by a bout of wildness in the 9th inning, as a walk, three hit batters, and two errors left the score 5-3. [11]

Major-league scouts were again aware. Houston and Pittsburgh saw him in Aberdeen, as well as the Phillies. However, APG was in the back yard of the Baltimore Orioles, and their influential scout Walter Youse recommended him.

When Private First Class Brabender returned to professional action, it was with the Bóer Indians in the Nicaraguan League. The season began in early November 1965, and on November 29, the Orioles selected him in the Rule V draft from the roster of the Dodgers’ Triple-A club, Spokane. As the organization stockpiled yet another strong young arm, Gene got the news down in Central America:

“One of the guys heard it on his short-wave radio and two days later I got a telegram from the club. The Pittsburgh scout told me I was eligible for the draft and I was hoping someone would take me. I mean, how’s anyone going to run [Sandy] Koufax or [Don] Drysdale out of a job?” [12]

On the surface, Gene’s numbers in Nicaragua were just fair (5-5, 3.52, though he did strike out 62 men in 62 innings). [13] He finished strongly, though, and Bóer club officials asked him to stay for the full season even though he had been scheduled to return in January [14]. In an extra game against Estrellas on January 24 to determine who would make the playoffs, he took a no-hitter into the 7th inning and won 9-1. [15] Then in the championship, which Bóer took 4 games to 1 over León, Gene won Game 3. He beat Minervino “Minnie” Rojas, the league’s top pitcher that year, 10-2. [16]

When Brabender reported to the Orioles camp in spring 1966, he had a couple of little misadventures. One day the team was traveling to the Gulf Coast on a 9:30 A.M. plane, but Gene and Karen both managed to snooze through two alarms. At 9:00 Karen rapped him on the chest to wake him. He jumped out of bed and, without glasses, ran smack into a wall. (Think Herman Munster, not Lurch.) Finding an alternate flight to Tampa, he packed hurriedly. He called a taxi, then another when the first cab was a no-show, and announced, “Buddy, we got some drivin’ to do.” He paid $20 for his ticket — ordering the clerk to “Write faster!” — and got on board just as the door was closing. Finally, he shelled out $12 more for a taxi to Clearwater. Manager Hank Bauer decided that was in effect a fine. [17]

Also in Florida, while fishing with fellow rookie pitcher Delano Hill, Gene fell out of their boat while trying to loosen a 75-cent lure from a tree. “‘Hill really cracked up when I splashed in the water,’ Brabender said. ‘When I got back in, Hill asked why I didn’t dive back in for my glasses. And I had a good reason. I can’t swim a lick.’” [18]

Once Gene was safely back on dry land and the field, pitching coach Harry Brecheen ordered him to throw just fastballs and sliders and to keep the ball down. [19] Bauer, who had previously called Gene a “sleeper”, [20] said, “I’m thinking about him as a long reliever now. But if he shows he can get the ball over the plate, he could be a short reliever too. He sure throws the ball hard and he’s really tough on righthanders. He might be a lifesaver.” [21] Brooks Robinson agreed. “He was one of those guys you’d like to bring out of the pen. He threw hard and dropped down from the side.”

By the time Bauer used his rookie, it was May 11, minutes before the roster cutdown deadline. (Clubs were then permitted to carry 28 players for the season’s first month.) In his big-league debut, Bender entered in the 10th inning against the White Sox at Memorial Stadium. He pitched a scoreless inning but a walk, a single and a hit batsman loaded the bases to start the 11th, before he balked home the eventual winning run, despite striking out four Chicago hitters.

In his next outing, versus Boston on May 17, Gene qualified for the win in relief as Baltimore scored four runs in the sixth inning. However, he had allowed four runs himself, all scoring on a grand slam by Rico Petrocelli. A rare scorer’s decision awarded the W to Eddie Watt.

Thus Brabender’s first victory in the majors came on June 8. It was a doubleheader, and the first game went 14 innings. In the nightcap, as the clock struck midnight, a local curfew in Washington, DC caused a suspension in the Orioles half of the 6th. Play resumed the next day with Bender (who had relieved Steve Barber in the third inning) still on the mound. Brooks Robinson observed that before the game, Gene “kept pacing in the dugout. He got a rubdown, and then walked some more. Once he lay down for a while and then got up again.” When he asked who was on the mound for the Senators (it was Dick Bosman), Gene declared, “Whoever he is, he’s going to get a big L strapped against him real quick.” [22] Indeed, the O’s rallied in the eighth and Watt got the save.

Deane Brabender, still in high school then, spent the summer of ’66 with his big brother. He kept a peanut box with the team’s signatures, including Gene’s pals Brooks Robinson and Boog Powell. Deane remembered that Gene was also friends with Frank Howard, who was just a short drive away in Washington. At least on the mound, Brabender owned “The Capital Punisher” — Frank went just 4 for 25 lifetime in their matchups, with 11 strikeouts. (Harmon Killebrew was a different story, though: 8 for 19 with 5 homers.)

Brooks Robinson remembered one of Howard’s hits off Bender well. “He almost got me killed one time. Frank Howard was the one guy I really, I wouldn’t say feared, but had extra respect for as a third baseman. He was so strong and hit the ball so hard. Gene dropped down from the side, Frank hit one over my head, and I jumped. But it was a day game — people were wearing white shirts and I couldn’t pick up the ball very well. The ball hit the left field wall. I said to Gene, ‘If I’d jumped at the wrong time, I might have gotten killed!”

Brabender finished the year at 4-3, 3.55. In the World Series that October, Baltimore swept the Dodgers in four straight games. The O’s posted three complete-game shutouts and needed just one reliever, Moe Drabowsky. Gene’s exuberance after the sweep caused sportswriter George Vecsey to coin a wry phrase years later. “Brabender’s Law” states that “The most inactive player during the World Series will be the most active in the clubhouse follies.” [23] “He went nuts. . .spraying champagne all over teammates as well as sportswriters, baseball officials, and innocent bystanders.” [24] Brooks Robinson noted, “Everybody was going nuts — but Gene really went over the top.”

Probably Gene’s best sustained stretch as a pro came in winter ball from December 1966 through February 1967. This time he was in Venezuela, with the La Guaira Tiburones. It was an amazingly tight race: Caracas and Lara tied for first at 31-29, while Magallanes, Valencia, and La Guaira all finished at 30-30. Last-place Aragua finished just three games out of first. The Tiburones won 16 of their last 22 games, led by Brabender. [25]

“The fireballing righthander climaxed his heroics by whipping Caracas twice on closing day, January 22. [He] hurled seven innings to win the first game that day and then came back to pitch the last three and one-third frames in relief to earn credit for the 11-inning nightcap. Earlier Brabender lifted La Guaira into contention with successive route-going victories over Caracas and Valencia.” [26]

Bender then defeated Magallanes 3-2 in 11 innings to bring the Sharks into the first round of the playoffs. [27] He finished the season at 13-7, 2.45, tying for the league lead in wins with Jim McGlothlin. He also had 147 strikeouts in 161 innings. Gene wasn’t finished yet — in the semifinals, he allowed just five hits in a 1-0 shutout over Caracas. [28] La Guaira went 4-2 in the round robin and faced the Leones yet again for the championship. At last, though, the Tiburones’ exciting run came to an end. Luis Tiant defeated Brabender in both Game 1 and Game 4 as Caracas took the five-game series 3-2. [29]

Despite his excellent showing that winter, Gene did not make the Baltimore staff to open the 1967 season. He was sent to Triple-A Rochester near the end of spring training. Although he started slowly, he went 8-6, 2.77 in the International League. Meanwhile, he was still performing his favorite stunt. “‘Frank Peters, one of my teammates, found a [tarpaulin] spike for me and I bent it,’ Brabender said. ‘But it was made of some kind of alloy and when I released the pressure, the spike snapped back into shape. First time I ever saw one like that.’” [30] While others tried their might over the years, none could match the feat with hands alone.

The Orioles recalled him in July as their staff was beset by injuries. Over the rest of the season, Gene was a regular in the rotation (6-4, 3.35 in 14 starts). He noted that at Rochester, he had rediscovered how to run his fastball in on lefthanders. [31] The best game of his career came on August 7. Against the Cleveland Indians, he pitched a four-hit shutout and struck out 12. Dodgers GM Buzzie Bavasi said that year, “If we ever made a mistake, it was letting Brabender get away.” [32]

Gene spent the entire 1968 season with Baltimore. As a swingman, his record (6-7, 3.31) was not up to his team’s high standard. His best outing came on May 5. In his first start, he fired a six-hit shutout against the Senators at D.C. Stadium — also connecting off Dennis Higgins for his first of two major-league homers.

Brooks Robinson had a favorite memory from that year, a story that Brabender would also tell himself. Brooks recalled, “We were out for dinner in New York one time, four of us, I think it was Gallagher’s Steak House. The waiter was really obnoxious. We didn’t leave him a very big tip. He came back to complain, and Gene stood up, put his hand on his shoulder, and said, ‘How far do you want to get tipped?”

In December 1968, the Orioles made a crucial trade that would help establish them as a power in the American League for several seasons. The team already had a lot of good pitching, but after they obtained Mike Cuellar from Houston, they were even deeper in starters. Thus, on March 31, 1969, near the end of spring training, Baltimore was dealing from strength when they sent Gene and Gordy Lund to the Seattle Pilots for Chico Salmón.

The front office’s thinking showed just how strong the Orioles had become. “‘The ideal situation is to have two utility infielders,’ [Harry] Dalton said. ‘It’ll give [Earl] Weaver more mobility and flexibility.’” Dalton added that while the club had not intended all along to deal Brabender, the pitcher had reported late and gotten little work. He also alluded to Gene’s conditioning, which turned out to be the wrong kind of workout. [33] The muscleman had spent the winter hoisting 150-pound crates of carp in Sturgeon Bay, Wisconsin. [34] He’d moved to his new hometown, on the scenic Door Peninsula in Lake Michigan, for the fishing and hunting. [35]

Brabender — who was fishing when the trade was made — was disappointed, but added, “I was half-way mentally prepared for this anyway.” However, he had to get the news to Karen, who was already on a ferryboat with their four-year-old son Kenny and dog, headed for Baltimore. [36]

Gene got off to a slow start with the expansion club, working mainly in relief. Toward the end of May, though, he rounded into form and embraced the opportunity the trade had given him to be a frontline starter. He got satisfaction the first time he faced Baltimore after the trade, going all the way in an 8-1 win on May 27. Then in a three-week stretch from June 13 to July 1, he racked up four more complete-game wins in five starts.

In the first of these games, at Yankee Stadium, Brabender again avenged a slight. Sportswriter Vic Ziegel (then of the New York Post) wrote, “Today Mel Stottlemyre goes after his seventh victory and Gene Brabender goes after whatever the Gene Brabenders of the world go after.” When the column was read in the clubhouse, Bender boomed, “Will someone point out that f***er to me?” “He must not have seen you in person, rooms,” said catcher Jim Pagliaroni. [37] Gene and the Pilots then prevailed, 2-1.

Eight days later, versus Kansas City at home, he threw his only shutout of the season — with a beer in the clubhouse between each inning. Fellow pitcher Dick Baney recalled, “You don’t see that every day.” [38] He didn’t say whether manager Joe Schultz (“Pound that ol’ Budweiser!”) winked at the fluid replacement strategy.

Brabender enjoyed another three-game winning streak in September, but then he dropped his last two decisions of the year, leaving him a game under .500 at 13-14, 4.37. He was the club’s leading winner, pitching a career-high 202 innings. One reason, in his view, was that Seattle let him bulk up. Whereas he had to keep his weight down to 220-230 pounds with the Orioles [39], “I weighed about 248,” he noted at the start of 1970. “I feel stronger and I have more endurance when I’m a little heavier. I have better control too.” [40]

Bender left his size 14 footprints throughout the pages of Ball Four. “Gene Brabender sometimes walks around bellowing ‘cowabunga!’” and “He looks like if you got a hit off him, he’d crush your spleen” were just two of many images. [41]

Being so imposing, Gene was appointed judge of the Pilots’ “kangaroo court.” Also threaded through the book were many pranks. When the Orioles visited Sick’s Stadium in June, they put little black and orange fish in their opponents’ water cooler — after finding their bullpen benches on the roof of the shed. Only Bender was strong enough to do this — or to rip a door off its hinges, something for which Jim Bouton got charged. After the knuckleballer was traded to Houston, he also found out that Brabender was the man who had nailed his shoes to the clubhouse floor, torn the buttons off his sweatshirts, and pulled his jockstraps out of shape. Shooting darts into the walls above guys’ heads with a homemade blowgun was another of Gene’s little pastimes. [42]

After just one year in Seattle, the Pilots moved to Milwaukee. Bender became the first Wisconsin native to appear for the Brewers. He was hoping that he could win 20 games. Unfortunately, even with family rooting him on at County Stadium, the presence of many local friends may have distracted him off the field. Despite the birth of his second son, Tony, the season was a big disappointment (6-15, 6.02). Gene held out for (and got) a raise, but then suffered an early leg injury [43] — and worse, again he started off with a sore shoulder. This time he could not work his way through it. “Big Bra” — articles from this period indulge in dreadful lingerie-based puns — couldn’t throw his hard sinker or his slider. He was just plain hittable. [44, 45]

On January 28, 1971, the Brewers traded Brabender to the California Angels for outfielder Bill Voss. The Angels viewed him as a short reliever. Lefty Phillips said, “We think he can be the answer. We need a man who can come in and throw the ball past a hitter or make him pop it up.” [46] Perhaps another hard thrower from Wisconsin, Ryne Duren, came to mind. For about a year Gene had been wearing prescription glasses that changed tint in the sun, similar to Duren’s dark lenses.

However, he did not make the team in spring training, as evidenced in an exhibition game against the Tokyo Giants. Brabender had loaded the bases and Phillips came out to the mound. “‘I told him if he didn’t get the next guy out, I would bring a weather report.’ The puzzled Brabender asked what a weather report was. ‘For you,’ said Lefty, ‘it could be showers.’” [47]

Assigned to Triple-A Salt Lake City, Bender went just 1-4, 8.36. Clearly still hurting, he pitched just 27 innings in 13 games and barely appeared at all after May. His biggest thrill as an Angel was meeting club owner Gene Autry; as a boy, Brabender had idolized “The Singing Cowboy” and never missed his movies. [48]

In the spring of 1972, Gene returned for a last chance with Salt Lake. Several men were battling for two open spots on the staff, though, and he had just an outside shot. [49] Though he said his arm felt great again [50], a later report said it hadn’t really improved. The Angels cut him in early April, and he then retired to “spend more time with family.” [51]

Brabender then got into the mobile-home business in Sturgeon Bay. He still pitched recreationally with Door County’s Cherry League (the peninsula is known for its cherry orchards). However, he gave that up in 1973 after he couldn’t see an incoming pitch and it beaned him. Deane lured him back for the league championship a couple of years later, though, so the brothers could form a battery for the first time. “He was out of shape and only throwing three-quarters speed, but he was still killing them. But then he gave up a homer and we lost 2-0!”

A thinly veiled version of Bender was visible on TV in 1976, when Ball Four became a short-lived sitcom. (Oddly enough, New York sports columnist Vic Ziegel, who had “dissed” Gene back in 1969, was a staff writer.) Series star Jim Bouton actually invited his teammate in from Sturgeon Bay to audition. He did come to New York, since he was not one of the people who resented the book. “He smiled about it,” said brother Darrell. “He had good things to say.” As it turned out, the big man was smaller than life in front of the camera. So, Bouton never got to ask about his nailed-down shoes, and 6-foot-8 former NFL defensive end Ben Davidson won the role of “Rhino Rhinelander.” It was the best thing in the unsubtle show. [52]

Around 1978, Brabender moved back to Black Earth. He had gotten divorced and the mobile-home business had ended badly. He then established a small construction firm, doing concrete work, siding, and other related jobs along with one of his sister Caryl’s classmates. From 1975 until his death in 1996, his significant other was Donna Meland.

In 1983, Gene suffered more business reverses. It came to the point where he had to sell his tool box, and he nearly had to part with his onyx-and-diamond World Series ring that July. He had used the ring, then valued at $6,500, as collateral for a business loan that carried a crushing 20% interest rate. When the loan went unpaid, though, the State Bank of Cross Plains put it up for sale via ads in two Baltimore newspapers. As John Steadman of the Baltimore Sun wrote in 1993, “Brabender was more than down on his luck. He retreated into the woods of Wisconsin and became a recluse.” Brabender told Steadman about how he lost his self-respect and fell into a deep depression – but with the support of family and friends, plus prayer, he emerged from oblivion. [53]

“When word of his problem got out, Brabender received a few hundred dollars in contributions to help settle his debt. He was still facing the loss of his ring until a relative of a friend came to his rescue. ‘The loan is paid off and I don’t have to worry about it any more,’ said Brabender. ‘The person involved wishes to remain anonymous. I know the people and they’re local, and this way, I can go to see him and pay him back in person.’”[54] This good Samaritan, a Madison executive named Donald Schaefer, held the ring in trust until Gene got a little more cash flow.[55] That came in part once he started drawing his major-league pension. Bender eventually reclaimed his most treasured asset; it is now in the family’s safekeeping.

Gene had boundless patience with young people. For example, he was repairing his brother Deane’s roof one summer but repeatedly climbed down to bait his niece’s hook as she learned to fish. Even so, he never coached baseball on any level, though he was always willing to offer verbal tips or meet young players down at the field for one-on-one sessions. Another former occupation did become an extra job — the old MP was a bouncer at a local dance hall. Rowdy patrons who had to leave always left quietly.

In December 1996, Gene promised to do the cement work on his sister Caryl’s new driveway. He never had the chance. The day after Christmas, he collapsed by the side of his parked truck at home in Arena, another small town west of Black Earth. His father said, “They figure he had kind of a stroke. He was out there by himself. A neighbor happened to drive by and saw him lying there. It happened so fast just like that.” [56]

In December 1996, Gene promised to do the cement work on his sister Caryl’s new driveway. He never had the chance. The day after Christmas, he collapsed by the side of his parked truck at home in Arena, another small town west of Black Earth. His father said, “They figure he had kind of a stroke. He was out there by himself. A neighbor happened to drive by and saw him lying there. It happened so fast just like that.” [56]

That evening, the neighbor saw the vehicle’s overhead light on, thought it odd, and then came back after noticing the light still on some time later. Brabender was taken to University Hospital in Madison, but nothing could be done. On December 27, Gene Brabender passed away.

The root cause was a brain aneurysm. Gene did not suffer a heart attack, as some stories state. (In fact, he became an organ donor; “whoever got that big heart sure was lucky,” said Deane.) Also, he was not farming, as the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel implied — the small shed next to his modest dwelling held his construction gear. One other point deserves a little extra clarity. While money was tight, and MLB’s Baseball Assistance Team reportedly lent a helping hand in an emotional time of need, there was some insurance as well to tide things over with the funeral.

Brabender was laid to rest in St. Barnabas Cemetery in the town of Mazomanie, north of Black Earth. He had been married in the parish’s pretty little Catholic church and had worshiped there. “God was always in his heart,” said his brother Deane. “You never heard him swear.” Thus he reacted strongly when Bouton and Pagliaroni once sang the Lord’s Prayer as the Pilots’ plane hit turbulence. Typically, though, he had a friendly word with “J.B.” right after. [57] Gene never let anything rile him very long.

This trusting, open-hearted man was deeply attached to his home turf. One especially telling quote from 1969 remained true:

“He prides himself in being Gene Brabender, no one else. ‘If the time ever comes when I snub the fellows I grew up with, I want someone to punch me in the nose to bring me to my senses. And I mean that. I’m pretty proud of the place.” [58]

His sister Caryl added, “He would stand by anybody. . .he would help anybody. He would have helped the Devil himself.”

Originally posted in May 2008; updated August 2012.

Grateful acknowledgment to the following members of Gene Brabender’s family: Caryl Brabender Zander (sister), Darrell and Deane Brabender (brothers), Brett Lucey (nephew), Amber Brabender (granddaughter). Thanks also to Jim Bouton (telephone interview, January 21, 2008), Brooks Robinson (telephone interview, April 24, 2008), Carroll Beringer, Danny Ozark, Don Oscar, Steve Schmitt, Marguerite Towson (editorial technician, United States Army Garrison, Aberdeen Proving Ground).

Notes

[1] Jim Bouton, Ball Four: Twentieth Anniversary Edition (New York: Macmillan General Reference, 1990), p. 91. Quote: Steve Barber.

[2] Ibid., pp. 93-94.

[3] Doug Brown, “Brabender Misses the Plane–But Orioles Forgive Hill Whiz,” The Sporting News, April 16, 1966, p. 34.

[4] J. Suter Kegg, “Orioles’ Brabender Ring Lardner Type,” Cumberland (MD) Evening Times, April 6, 1966, p. 33.

[5] Lew Cornelius, Capital Times (Madison, WI), April 28, 1961, p. 21.

[6] “Big League Pitching Standout on Bomber Squad,” APG News – Harford Democrat Observer (MD), September 11, 1964.

[7] Gordon Beard, Birds on the Wing: The Story of the Baltimore Orioles (New York: Doubleday, 1967)

[8] Lew Cornelius, Capital Times (Madison, WI), March 18, 1961, p. 11.

[9] Ross Newhan, “Angels Ask: Can Big Bra Regain Maiden Form?” The Sporting News, February 13, 1971, p. 43.

[10] “Brabender Marriage Takes Place,” Wisconsin State Journal, May 6, 1964, p. 15.

[11] Various stories, APG News – Harford (MD) Democrat Observer, 1964-65.

[12] Brown, op. cit.

[13] Horacio Ruiz, “Oliver, Lundgren, Scott Bat Kings of Boer Victory,” The Sporting News, February 12, 1966, p. 25.

[14] Horacio Ruiz, “Home Run Heroics Put Oliver, Hicks and Alvarez in Spotlight,” The Sporting News, January 29, 1966, p. 27.

[15] Horacio Ruiz, “Sharks Cop Crown; Hurler Rojas Lifts Leon Into Playoffs,” The Sporting News, February 12, 1966, p. 30.

[16] Julio C. Miranda Aguilar, “Final con olor a revancha,” El Nuevo Diario (Managua, Nicaragua), January 22, 2007.

[17] Joe Snyder, “Baseball Characters: Enter Brabender,” Hagerstown (MD) Morning Herald, April 8, 1966, p. 21.

[18] “It Takes Gene Two Days For First Win,” Waterloo (IA) Daily Courier, June 10, 1966, p. 14.

[19] Snyder, op. cit.

[20] Doug Brown, “Orioles Stirred Up Plenty of Rumors–Result: One Trade,” The Sporting News, December 18, 1965, p. 12.

[21] Brown, “Brabender Misses the Plane–But Orioles Forgive Hill Whiz”

[22] “It Takes Gene Two Days For First Win”

[23] George Vecsey, “Brabender’s Law Works Again,” New York Times, October 18, 1983.

[24] Mike Shannon, Tales from the Dugout (Lincolnwood, IL: Contemporary Books, 1997), p. 27.

[25] Eduardo Moncada, “A Frantic Finish–Two-Way Flag Tie,” The Sporting News, February 4, 1967, p. 39.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Eduardo Moncada, “Pena, McGlothlin, Brabender Mound Heroes in Playoff Games,” The Sporting News, February 11, 1967, p. 39.

[28] Eduardo Moncada, “Aparicio Bat Sparks Late Shark Surge,” The Sporting News, February 18, 1967, p. 39.

[29] Eduardo Moncada, “Tiant, Casanova Cook a Feast for Champion Lions,” The Sporting News, February 18, 1967, p. 33.

[30] “Orioles’ Animal Tossing the Ball,” Port Arthur (TX) News, August 8, 1967, p. 20.

[31] Doug Brown, “The Sunflower Is Brabender’s Favorite Bloom,” The Sporting News, December 2, 1967, p. 49.

[32] Phil Jackman, “Orioles Chirping Over Stylish Hill Jobs by Gene Brabender,” The Sporting News, August 26, 1967, p. 17.

[33] Doug Brown, “Salmon to Bolster Baltimore’s Bench,” The Sporting News, April 12, 1969, p. 52.

[34] Hy Zimmerman, “Nothing Fishy About Brabender’s Goal,” The Sporting News, March 7, 1970, p. 26.

[35] Monte McCormick, “Gene Madison Native Too,” Wisconsin State Journal, April 8, 1970, Section 2, p. 2.

[36] Brown, “Salmon to Bolster Baltimore’s Bench”

[37] Bouton, p. 216.

[38] Larry Stone, “Endearing and Enduring: The 1969 Seattle Pilots,” Seattle Times, July 9, 2006.

[39] Hy Zimmerman, “Big Gene: Pilots’ Pride, Joy,” The Sporting News, October 4, 1969, p. 16.

[40] McCormick, op. cit.

[41] Bouton, pp. 314, 245.

[42] Bouton, pp. 163, 205, 345, 383, 440.

[43] Zimmerman, “Nothing Fishy About Brabender’s Goal”

[44] Larry Whiteside, “Brewers Enjoy Snug Feeling With Big Bra,” The Sporting News, July 4, 1970, p. 20.

[45] Larry Whiteside, “Can Brewers’ Big Bra Snap Back Next Season?” The Sporting News, December 12, 1970, p. 60.

[46] Newhan, op. cit.

[47] Dick Miller, “New Angel Torborg Eager to Shuck Benchrider Role,” The Sporting News, April 3, 1971, p. 30.

[48] Dick Miller, “O’Brien Like Three-Way Insurance for Angels,” The Sporting News, March 27, 1971, p. 31.

[49] Ray Herbat, “Moss Taps Reynolds for S.L. Opener,” Salt Lake Tribune, April 7, 1972, p. 16B.

[50] Ray Herbat, “Fighting for S.L. Jobs,” Salt Lake Tribune, April 4, 1972, p. 15B.

[51] “Brabender Quits Baseball,” Oshkosh (WI) Daily Northwestern, April 26, 1972, p. 31.

[52] Bouton, p. 404.

[53] John Steadman, “After hitting bottom, Gene Brabender rings in a new year and a new life,” Baltimore Sun, January 11, 1993.

[54] “Pitcher gets ’66 ring back,” Syracuse Herald-Journal, July 21, 1983, p. D-2.

[55] Steadman, “After hitting bottom, Gene Brabender rings in a new year and a new life.”

[56] “Ex-Brewers pitcher Brabender ‘loved baseball’”, Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, December 31, 1996.

[57] Bouton, p. 246.

[58] J. Suter Kegg, “Spring Training Taps by Kegg,” Cumberland (MD) Evening Times, April 3, 1969, p. 15.

Sources

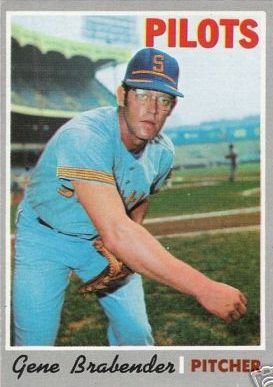

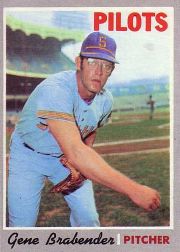

Gene Brabender’s Topps baseball cards, 1967 and 1970

www.mlb.com

www.retrosheet.org

www.findagrave.com (showed Brabender’s Army rank)

Professional Baseball Player Database V6.0

www.blackearth.org

www.rootsweb.com (more on the origins of the town of Black Earth)

University of Wisconsin-Whitewater Registrar’s office

Photo Credits

The Topps Company, Amber Brabender

Full Name

Eugene Mathew Brabender

Born

August 16, 1941 at Madison, WI (USA)

Died

December 27, 1996 at Madison, WI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.