Andy Coakley

Andy Coakley is remembered most as “Lou Gehrig’s coach” in his 37 years as head of Columbia University’s baseball program.

Andy Coakley is remembered most as “Lou Gehrig’s coach” in his 37 years as head of Columbia University’s baseball program.

But this overlooks his extensive influence on the game. Once a promising right-hander with Connie Mack’s Athletics in the early 20th century, Coakley was also a labor pioneer, a forward-thinking league organizer, a team owner, and a bird-dog scout, before spending four decades as a college coach — three years at Williams, then at Columbia.

Andrew James Coakley was born on November 20, 1882. He was the ninth of ten children of Irish immigrants Michael (who ran a grocery store) and Hannah “Annie” Sullivan Coakley. The couple — both of whom crossed the Atlantic in their youth — was in San Francisco, California, when their first child, Edward, was born in 1869. They relocated to Providence, Rhode Island, the following year. Eugene, Mary, John, Nellie,1 Agnes, Nora,2 and James soon followed, though Mary passed away at age two in 1874.

Although Andy had a younger sister, also named Mary, she did not survive past adolescence. James died at age six, and Eugene and Agnes didn’t see 30.

Young Andy’s first taste of baseball was through his local parish, St. Michael’s. The coach, Tim O’Neil, was later renowned as “King of the Sandlots” for organizing his nationally acclaimed, eponymous youth leagues throughout Providence. He adhered to the credo later made famous by Father Flanagan: “There is no such thing as a bad boy.”3 The philosophy resonated with Coakley as a college coach.4

Baseball consumed the boy’s thoughts. Neighbors later recalled how deliveries from Michael Coakley’s store in South Providence were sometimes delayed because Andy had stopped to practice pitching on the way.5

His dedication developed him into a standout pitcher at Classical High School, an academically demanding all-boys public school.6 Despite being tall and ungainly — 6’0” and 145 lbs. — Coakley had a killer fastball that enabled him to pitch in two championship games in the Inter-Scholastic League.

Coakley entered the prep school at College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts, in the fall of 1900. He was rapidly establishing himself among the amateur pitching elite.7 After going 6-7 with three shutouts in his first spring with Holy Cross’s varsity nine, Coakley found work with the Saint John Roses in New Brunswick, Canada. But the rival Alerts dashed the Roses’ league championship hopes with a decisive sweep of a Labor Day doubleheader,, in which Coakley hurled 14 innings of one-run ball, only to lose, 3-1, on a walk-off home run.8

On his return to Holy Cross in 1902, Coakley devastated opponents. An 11-inning, 14-strikeout, 1-0 three-hitter at Yale on April 26 earned him widespread recognition.9 His reputation grew when he outdueled Harvard ace and future major-leaguer Walter Clarkson, 2-0, on May 24. Spectators arrived in droves to watch “the great Coakley;” a home crowd of 2,000 showed up for a cold, dreary May 28 game against Georgetown.10

Coakley was responsible for 10 of Holy Cross’s 18 victories that spring, including six shutouts, still a school record in 2018. His control was impeccable for a college pitcher; in those two seasons, he allowed 53 walks in 241 innings pitched. In that same span, he struck out more batters (188) than he allowed hits (172).11

Ball clubs lined up for the young fireballer’s services for the summer. As early as March 15 the Malone club of the Northern New York League was negotiating a contract, which Coakley accepted by telegram shortly thereafter.

But when manager William J. Tucker of rival Potsdam approached him with an offer too good to turn down — $50 a week with $25 up front — Coakley snatched it. The Malone club protested, threatening to “withdraw from the league” if Coakley’s contract-jumping were permitted.12

Coakley’s case went before league headquarters in Plattsburgh on May 27, where the executive board (largely composed of the league’s managers) ruled that he was under obligation with Malone.13 Although club-jumping was prevalent back then (including at baseball’s highest level, with the upstart American League luring away the National League’s best), local media lambasted the star collegian. One observer said, “We wouldn’t have him in Malone if he played for one cent a year.”14

It wouldn’t be the last time a league would blacklist Coakley over a contract dispute.

Coakley eventually signed with Old Town of the short-lived Northern Maine League, though he also played for a team in Lebanon, New Hampshire, at some point that summer.

Meanwhile, another scout had taken notice of Coakley — Thomas McGillicuddy, brother of the manager and part-owner of the Philadelphia Athletics, Connie Mack. The Tall Tactician offered Coakley a contract in June, but he declined. Coakley also turned down the Detroit Tigers.15 Coakley may have been first noticed by the sponsor of one of those summer teams for which he played, who was friendly with Mack.16 The rules on professionalism could be bent somewhat in collegiate athletics then; however, the American League was clearly out of bounds, at least for the time being. Having finished prep school, Coakley planned to matriculate at the college that fall, not to drop out. Pitching for the Holy Cross varsity must have crossed his mind. But Coakley, like many college players of the day, succumbed to the very pressure for which he would later call out Lou Gehrig — playing professionally under a pseudonym.17

On September 17, 1902, Coakley told his mother he was going to Worcester to see about a room on campus. A few hours later, a young man named “McAllister” stepped off the train in Philadelphia and onto the mound at the Athletics’ Columbia Park. Word had it he was from Iowa, or perhaps Colorado.18 He allowed six hits (five were doubles) and struck out six in the complete-game 6-5 victory over Washington. Afterward, he boarded another train and went home.19

A story (likely embellished) said that the kid “was so fast and so deceptive” that the Senators attempted to steal Philadelphia’s signals, and that when Coakley and catcher Ossee Schrecongost discovered what they were doing, they secretly changed them. Tipped off by third base coach Ed Delahanty, Washington’s next batter, Bill Coughlin, had prepared to swing at a curveball and was flattened when Coakley’s fastball inside didn’t break.20

“The ball fractured his jaw and knocked out a lot of his teeth and I had visions of being tried for manslaughter,” Coakley recalled.21

Coughlin, who batted clean-up, was hit in the first inning, so the whole sign-stealing scenario is less believable. However, decades later, when Coughlin was coaching at Lafayette and Coakley at Columbia, he would flash his gold teeth and joke with Coakley about when he was going to pay the dentist’s bill.

“McAllister” returned to Philadelphia to start two more games that month. Splitting the decisions, he totaled a 2-1 record with a 2.67 ERA. He watched from the bench as the Athletics clinched the AL pennant.

Unfortunately, Boston Globe writer Tim Murnane was familiar with Coakley of Holy Cross and made the connection with “McAllister.” The rumors reached Rev. Daniel Quinn, the college’s athletic disciplinarian. Summoned before the faculty just before Christmas, Coakley confessed, calling Mack a “personal friend” whose team was fighting for the pennant and desperate for pitchers.22 On January 8, 1903, Coakley — “without a doubt the best college pitcher in the country,” Quinn said — was suspended from collegiate competition the following spring.23

Coakley continued his studies. He must have been at least a fair student, since (before grade inflation) one needed at least a 60 average to compete for Holy Cross. He turned down an offer to join an independent club in Woonsocket, Rhode Island; his family was opposed to him playing professionally.24

But he practiced with the Holy Cross team to stay fresh and helped coach them that spring. He also worked out with semipro clubs, including Milford. The brand-new Holyoke Paperweights of the Connecticut League brought him in as a “ringer” under the name of “Sullivan” to pitch Opening Day and a few other games.25 After finishing examinations in mid-June, he reported back to Philadelphia.

As Andy Coakley, though, he did not reprise “McAllister’s” flashes of brilliance. The Athletics’ rotation already included two respectable rookies, Weldon Henley and Chief Bender, in addition to steady veterans Rube Waddell and Eddie Plank. In the few opportunities Coakley had to pitch that summer, he faltered. A disappointed Mack sent him to Lebanon of the Tri-State League for more seasoning on August 2. When Coakley returned on September 5, first-place Boston slaughtered him, 12-1, in a contest thankfully shortened by darkness. Coakley finished 1903 at 0-3 with a 5.50 ERA.

Coakley followed a similar routine in 1904: studying at Holy Cross until the end of the term and participating in athletics when he could. In a basketball game against the senior class, he scored five of the sophomores’ seven points in those primitive days of the sport.26 He also coached baseball for the Highland Military Academy in Worcester.27 On June 20, he was back with Philadelphia, but was farmed out to Montpelier, Vermont, within days. He might have been suffering from malaria.28 The Athletics’ pitching staff was as strong as the year before, but, with the team one game out of first place in the loss column on August 29, Mack recalled Coakley. The upcoming road trip had a slew of doubleheaders. Paired with college pal Pete Noonan behind the plate, Coakley returned to form, going 4-3 with a 1.89 ERA in eight starts, though the Athletics stumbled into fifth place.

After that, Coakley finally left Holy Cross. Why? Perhaps he had validated Mack’s confidence in his talent. Maybe it was the promise of a full year’s contract. Or he might have believed that following the team’s training regimen from Day One would give him the best chance to crack the rotation, headed by future Hall of Famers Waddell, Plank, and Bender. But according to Coakley, the matter was simpler: “I definitely gave up college when they handed me a textbook entitled ‘Ars Discendi,’” he said. “It was all in Latin which was too much for me. It was more fun to listen to Rube Waddell.”29

For a dropout, Coakley left an impression. Two decades later, writer Irving McDonald’s series of morally idealistic books for Christian boys featured an All-American athletic hero, “Andy Carroll of Holy Cross.” The name was reputedly a combination of Andy Coakley and Ownie Carroll, another clean-cut alumnus who also went on to a major league career.30 Holy Cross inducted Coakley into its collegiate hall of fame in 1958.

Ahead of the 1905 season, Coakley’s finest, he knew he had to be in shape. Thus, he wintered in Jacksonville, Florida, later claiming he was one of the first players to go south to prepare for the upcoming season.31 Pitchers then typically threw for only about a week before the exhibition schedule began.

The Athletics held camp in New Orleans. Coakley, though still technically a rookie, felt accepted right away by the veterans. “Nobody on our club gave me the business,” he recalled a half-century later. “I was treated the way any ballplayer would want to be treated.”32

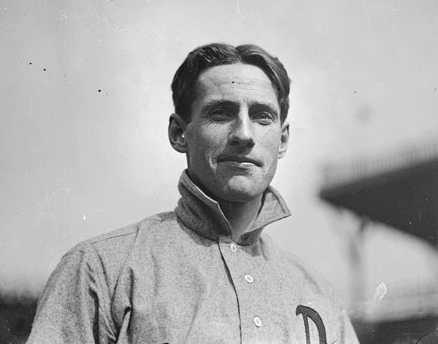

Writers liked him because he was intelligent and articulate. He received a sporadic byline in the Philadelphia North American, reporting from training camp, because he was “in absolute command of the college dialect.”33 Media outlets dubbed him the “Beau Brummel of Baseball,” for his clean-cut, well-dressed appearance.

Coakley and Noonan (sold to St. Paul at the beginning of the season) also became fast friends in camp with “two of the toughest men on the club, by reputation,” the wayward Waddell and his battery mate Schrecongost. As Coakley recalled, about 75 percent of the club didn’t drink. “Remember, Connie Mack was our manager,” he said.34 Thus, Waddell’s off-the-field antics and affinity for the bottle were that much more prominent. Coakley would later regale his audience with Waddell tales whenever asked about his Athletics days.

Coakley’s arsenal of pitches had grown; in addition to his fastball, he possessed “an assortment of curves, shoots, and drops,” said the Philadelphia Inquirer after a 1-0, four-hit victory over New York on July 1. Waddell, who won the pitching Triple Crown that year, might have overshadowed Coakley’s accomplishments, but Coakley was still among the game’s best. Contemporary records showed Coakley compiling the league’s top winning percentage, at 20-6 (or 20-7 or 20-8, depending on the source) to Waddell’s 27-10 (or 26-11 in some newspapers).35 (More recent revisions put Coakley’s record at 18-8 with a 1.84 ERA, the latter fourth-best in the AL)

At bat, Coakley was notoriously bad, even for a pitcher: a career .117 batting average in the majors, with just four extra-base hits. When asked toward the end of his career to select the “most notable achievement” in the history of the game, he chose, “That safe hit I made back near the close of the 1905 season.”36 Babe Ruth, in a ghostwritten column, labeled Coakley one of the game’s all-time worst hitters (despite likely never playing against him).37 Detroit’s Sam Crawford used to imitate Coakley’s awkward crouch of a stance.38

After barely winning the AL pennant over Chicago, the 1905 Athletics were no match for the runaway NL champion New York Giants in baseball’s second World Series that fall. The A’s were flattened, four games to one.

After barely winning the AL pennant over Chicago, the 1905 Athletics were no match for the runaway NL champion New York Giants in baseball’s second World Series that fall. The A’s were flattened, four games to one.

Coakley started Game 3, opposing the great Christy Mathewson in front of a Philadelphia crowd of about 11,000 who braved a biting wind. Burned by five errors that let in seven unearned runs, Coakley took the 9-0 loss (and a bruised arm from one of Matty’s pitches). Years later, Coakley would admit that he had been hardly effective,39 having allowed nine hits and five walks. He’d also lost some intensity from warming up a day earlier, before rain (or more likely lagging ticket sales, possibly because of the poor weather)40 postponed his start.

Coakley might never have pitched during the Series if not for a bizarre encounter with Waddell: the “straw hat” incident. There are many different retellings of the story, which essentially involved The Rube going after Coakley’s straw hat and ending up with an injured arm in the ensuing scuffle. Mack denied that this was what ended Waddell’s season; rumors persist that it was a cover for Waddell’s entanglement with gamblers.41

In any event, Waddell’s absence for the last month of the regular season took its toll on the staff. The Sporting News reported them “overworked” in early October and claimed young Coakley to be suffering from a “lame shoulder.”42 Mack said that the junior pitcher had lost 15 pounds in those final weeks.43 But Coakley insisted, in hindsight, that a healthy Waddell would not have made a difference in the series outcome, “since we did not score a run in the games we lost.”44

As the 1906 season began, Coakley had lost something from the year before. When healthy, he pitched well, but he often wasn’t. A bad “cold and aches” in May sent him to the mountains in Massachusetts to recover.45 He frequently went a week or more between starts. The Sporting News reported during the summer that Coakley was “18 pounds underweight, minus an appetite and lacks strength,” but that otherwise there was nothing really wrong with him or his arm.46

Connie Mack asked for waivers on his ailing pitcher in mid-July, but could not make a deal that would have sent him to Providence of the Eastern League. He permitted Coakley to take a few weeks off instead, ostensibly to get better, but also to get married.

Her name was Martha May Gray, but everyone called her Mattie. Although she was born in Philadelphia in May 1886, her family had relocated to New York around 1900. Described as “an enthusiastic baseball fan,” Mattie attended a few Athletics games the previous year. A cousin introduced her to Coakley, and “it was a case of love at first sight.” They were married in Philadelphia on July 16, 1906, in a “very quiet” ceremony.47

They honeymooned in Vermont, where Coakley made a discovery that demonstrated his keen eye for talent. Watching semipro ball one day in Montpelier, a young shortstop caught his eye — Eddie Collins, who would be entering his senior year at Columbia as captain of the baseball team. Coakley immediately wired Mack of the find, and “Eddie Sullivan” was playing for the Athletics before season’s end. Collins, too, was caught and stripped of eligibility upon returning to finish his degree at Columbia that fall. But after a 25-year Hall of Fame career, that became a mere footnote.

Coakley was also said to have tipped off Connie Mack to Dave Shean, an infielder from Fordham University. Shean played briefly for the Athletics in September 1906 and had a modest major league career with six teams, including the 1918 champion Boston Red Sox.48

Coakley finished 1906 at 7-8 with a 3.14 ERA, pitching about half as many innings as he had in 1905. Within a month after the season ended, Coakley, residing in West Philadelphia49 and thinking ahead about how to provide for his new bride after his baseball career, had enrolled in the University of Pennsylvania dental school.50

But on December 12, Mack asked for waivers again on Coakley and shipped him off to the Cincinnati Reds. The Reds’ own concerns echoed Mack’s.

“The only question regarding Coakley,” said Reds manager Ned Hanlon upon the acquisition, “is his health.”51

Coakley insisted repeatedly during of the offseason that he had recovered from his various ailments. But he wasn’t reporting to Cincinnati if the team was going to give him a lukewarm reception.52 Coakley must have gotten compensation or assurance, because according to the University of Pennsylvania archives, he never earned his diploma (though initially he took his dentistry books with him to Cincinnati with the intention of returning). He often received a “Dr.” in front of his name in print, anyway, and many newspapers referenced his dental training.53

True to his word, Coakley stayed healthy in 1907, pitching more innings than ever, 265 1/3. His 17-16 record (on a team that won just 66 games) was the only one among the regular Reds starters above .500, and he tied with Bob Ewing (17-19) for the team lead in wins. His ERA was 2.34, over a run less than the league average.

Two pitches in a game against the Giants on June 18 marked this otherwise inauspicious season for Coakley. In the fourth inning, he beaned Roger Bresnahan, knocking the star catcher unconscious. Feared dead, Bresnahan was given last rites while he lay on the field, then rushed to Seton Hospital.54 The next batter, first baseman Dan McGann, had his wrist shattered by an inside pitch.

Contemporaries believed both incidents to be accidents. But the damage had long-lasting effects.

Bresnahan spent the next ten days in the hospital developing an early prototype for a batting helmet. In his first game back on July 12, he collected two hits off Coakley, who took a 3-2 loss.

McGann, already on the edge of decline, missed nearly two months and was never the same. He was out of major league ball by the end of 1908, sank into depression, and committed suicide in 1910.

A few months later, Coakley (after disclaiming he’d ever been to war) compared hitting a player with a ball to “shooting a man in battle — you worry about it for a moment, and then go about your business, shooting a few more, if necessary.” Even though he felt “exceedingly sorry for both Bresnahan and McGann,” he pitched full speed to the next batter, Bill Dahlen. “[A]s for these or similar accidents taking a pitcher’s nerve away,” he finished, “there isn’t a chance, provided the pitcher has any nerve in the first place.”55

Coakley’s wit and ability to think things through was often recognized. Hans Lobert, a Carnegie Mellon-educated infielder, enjoyed his company. He remembered that in the middle of an argument Coakley would say, “Being unable to assume an initial premise with any tolerable degree of accuracy, I am loathe to assert a conclusion fearful lest I should err.”56

Coakley had a tendency for mind games on the field, too. At Pittsburgh in 1908, he walked the great Honus Wagner twice in early innings rather than face him. When the Flying Dutchman came up in the seventh with two on, Coakley threw three pitches nowhere near the plate. Wagner tossed his bat, assuming he would be intentionally passed again. The fourth pitch was a strike down the middle; Wagner, caught off guard, embarrassedly readied himself again to hit. Coakley then threw another wide one, taking the bat out of Wagner’s hands.57

Coakley also correctly forecast the increasing popularity of the spitball. He said, “When the spit ball craze became strong about two years ago all the amateur twirlers and bushers took it up. Many of these boys have developed, and as they graduate into fast company they still stick to the spit ball as their best piece of stock in trade.”58

Before the 1908 season, Coakley vowed to “winter in the woods in order to get as strong as an oak” and not to open a single scholarly book.59 He headed to Jefferson, Massachusetts, where he reportedly gained ten pounds.60 He was signed by early February. Some officials, such as John E. Bruce, the secretary of baseball’s National Commission, proclaimed that Coakley would be the Reds’ best pitcher.61

But 1908 was marked by hard luck; by early September, Coakley’s ERA was 1.86, but his record was 8‑18. The abysmal Reds gave him just 2.18 runs per start.

Restless in Cincinnati, Coakley asked Reds president August (Garry) Herrmann for a trade, claiming that he didn’t enjoy being called a “hard luck pitcher” and that the southern Ohio climate didn’t agree with his unpredictable health. Specifically, Coakley wished to go to New York. It would put him closer to family, plus the Giants were in pennant contention.62 Giants manager John McGraw wasn’t interested, but Cubs president Charles Murphy was hot on the idea. Chicago was another player in the three-team NL race, and player-manager Frank Chance agreed that an extra arm of Coakley’s caliber might put them over the top. The sale was completed on September 2.

In his first start for the Cubs, on Labor Day, Coakley hurled a complete-game, four-hit shutout against his old team. In his next outing, he yielded two runs in 1 1/3 innings against St. Louis, but Chicago won in 12. Coakley rebounded with a five-hit 3-2 victory in Philadelphia on September 21 (both runs scored on an error), and the next day, the Cubs, opening a series with the Giants, slid into a tie for first place.

On September 24, the day after the controversial tie game that ended when the Giants’ Fred Merkle failed to touch second base, the Cubs made a vain effort to force the Giants to forfeit. Coakley went to the mound to throw a few pitches before New York showed up, but neither the Giants nor the umpires were notified of the Cubs’ intention to pick up where the teams left off, so the farce was met with laughter.63

The two teams finished tied atop the standings, forcing the unresolved “Merkle game” to be replayed, which the Cubs won for their third straight pennant. Chicago then steamrolled Detroit in the World Series for back-to-back championships.

Coakley was ineligible for the World Series roster because he joined the team after August 31, yet he was dismayed that the Cubs had not given him a share. Without his two wins down the stretch, the Giants would have won the pennant.64 The AL champion Tigers, in comparison, had rewarded everyone who contributed, including the batboy.65 The Cubs (who had a bigger pot) looked like penny-pinchers. Sporting Life reported that Frank Chance had been in favor of acknowledging everybody, but was overruled by the rest of the players on the team.

Wintering in New York, Coakley grew progressively bitter over the snub. Chicago management had reportedly conceded Coakley $500 — or so the story went — but if it ever was agreed upon, no such money reached him.66 When he protested, Chance pointed out that Coakley had joined the club understanding that he would not partake in any potential World Series earnings.67

So Coakley took the only logical next step in the age of the reserve clause — he held out on his 1909 contract. Chance considered trading him, rather than risk him becoming a clubhouse cancer.68 Charles Murphy entertained sending Coakley and pitcher Chick Fraser, another holdout, to the minors if they didn’t report.69

Eventually, Coakley signed in early April for $2,700 — more than he expected, but not as much as he had hoped.70 Still, missing spring training had left him short of peak condition.71 He did not make his season debut until May 3 — and he got shelled, lasting just two innings and giving up seven runs (four earned). Coakley never wore a Cubs uniform again.

On May 12, Chicago optioned the disgruntled right-hander to Louisville of the American Association (along with Fraser and pitcher Carl Lundgren) for $1,500. He refused to report, threatened to retire, and went home. By late May, Coakley had resurfaced with a semipro team in New Brunswick, New Jersey.72 He then signed with Newburgh (New York) of the new outlaw Eastern Baseball Association.73 In early June, he’d latched onto Reading (Pennsylvania) of the Tri-State League.74 Meanwhile, Murphy tried to transfer Coakley back to Cincinnati, but Coakley wouldn’t accept that assignment, either.75

On June 4, flag-raising day for the defending champions, Murphy announced that he would divvy a $10,000 World Series bonus pool “only to those who helped win the third straight National League pennant and are helping to win the fourth.”76 Since Coakley had been demoted from the Cubs, he didn’t meet the second condition.

In July, Coakley agreed to manage and pitch for the semipro Manhattan baseball club, paired with ex-Red Sox backstop Tom Doran.77 He struck out 33 men in back-to-back games during his first week.78 Pete Lamer, an ex-Reds teammate, also caught for the team,79 whose home field was on the Bronx border in Marble Hill. Coakley also pitched for a semipro team in Litchfield, Connecticut, that summer.

In the winter, Coakley took up indoor baseball, a smaller version of the game played in gyms with rubber-soled shoes. By 1911, he’d become one of its staunchest promoters. Big-league stars including Mathewson, Willie Keeler, Heinie Zimmerman, Hal Chase, Johnny Evers, and Eddie Collins used Coakley’s indoor baseball team to keep in shape during the offseason.80 Today, it’s played outdoors and called softball.

As Coakley fought hard to secure his official release from Louisville, he focused on improving his Manhattan semipro club, making plans to “furnish Sunday attractions” and upgrade the diamond for the 1910 season.81 Meanwhile, rumors swirled about where he would be headed — possibly to manage Syracuse,82 or to pitch for his hometown Providence.83 He also assisted college pitchers at Princeton around that time.84

In February 1910, Coakley hired attorney Dave Fultz, an ex-teammate on the ’02 Athletics, to file a $3,280 suit against Charles Murphy for breach of contract.85 The suit alleged that the Cubs, in sending Coakley to Louisville the previous year, had weaseled out of paying all but $420 of his $2,700 salary. The Cubs admitted a contract existed, but that it specifically stipulated they could dismiss Coakley at will. As for the other $1,000, Coakley claimed the right to a percentage of the Cubs’ exhibition game receipts, which the Cubs outright denied.

Coakley might have needed money after a spring of brutal weather in New York.86 Thus, he reluctantly reported to Louisville in June. Colonels President William Grayson Jr. said he had “pleaded” with Coakley to rejoin the club before the season, but Coakley never signed the contract, and Grayson withdrew the offer.87 Now that Coakley was crawling back months later, Grayson was only willing to offer less money. On July 4, likely owing to this new salary dispute, Coakley was suspended for insubordination and fined $50, which he refused to pay. The Louisville club hastily sold their lost cause to Montreal. Again, Coakley rebelled, refusing the assignment until his claims with Louisville were settled.

Garry Herrmann, who doubled as chairman of the National Commission (the major leagues’ governing body in the days before they had a Commissioner), sprang into action. He wired secretary John H. Farrell of the National Association of Professional Baseball Leagues (the minors’ governing body). The message read: “I wish you would notify your respective clubs not to play with any team that Player Coakley is connected with.”88 Word reached Coakley on August 12.

That same day, Coakley claimed to have secured his release papers from Montreal for $500, becoming a free agent in order to sign with Elmira (New York) on August 25. Or perhaps, as a conflicting report suggested, his release was purchased when he wired Montreal the money on August 29, four days after he’d jumped clubs.89 Either way, it probably didn’t matter. Because Coakley had never reported to Montreal, the team had never formally completed the transaction with Louisville. This left Coakley still the property of the Colonels and thus subject to their suspension.90 He pitched one game with Elmira, one-hitting Albany, before Farrell interfered, informing umpires and managers of Coakley’s ineligibility and throwing the game out. 91

The National Commission then took the suspension a step further upon discovering Coakley had arranged exhibitions between his Paterson semipro club and both the Highlanders and Giants in August. It banned Coakley from organized baseball until the minor league matters were resolved. Even his semipro ventures were no longer allowed near any professional clubs.

Feeling like he had “been double crossed 17 different ways by the National Association,” Coakley threatened suit against Farrell (who, he believed, was trying to force him out from the Paterson club in order to absorb it into the New York State League).92 Despite never paying the $50 fine to Louisville from his July suspension, Coakley maintained that Louisville also owed him $55 in back salary. Still, even after he offered to pay the fine under duress if Louisville would lift his suspension, the powers that be were unresponsive.

Players throughout professional ball realized that Coakley had gotten a raw deal for attempting to challenge the system. Coakley’s squabbles with the owners and administrators would be a catalyst in the formation of the Players’ Fraternity, an early attempt to unionize (headed by Fultz) a few years later.93

But Coakley’s blacklisting also ushered in the next phase of his career. For one, he scouted for his friends in major league ball, including the Reds.94 (Despite Garry Herrmann’s role as head of the National Commission, Coakley had a working relationship with the Cincinnati management.) More importantly, he filled an opening for a baseball coach at Williams College in Williamstown, Massachusetts — first as a two-week replacement, but the position became permanent in March.95 He was resourceful: after a harsh winter left the school’s home field in disarray, Coakley arranged for the team to practice in South Orange, New Jersey, for Easter vacation. The team responded with five straight victories to start the season. They finished 9-5, and Coakley, who had been passing the time for $50 a game with Whitinsville (Massachusetts) in the Mill League (a semipro circuit made up of local mill workers), made preliminary plans to return to his semipro club in Paterson.

In late March 1911, the National Association reinstated Coakley; a few days later, the National Commission followed suit. The decision may have been predicated on a thorough investigation ordered by Herrmann to show cause for the suspensions of over 450 players by minor-league clubs.96 Coakley had petitioned AL President Ban Johnson for reinstatement in January; thanks to the scouting work he did for Herrmann, his latest appeal may have had some pull. The terms may also have stemmed from a compromise.97 Coakley had appealed to the National Commission to force the Cubs to pay him his due the previous December, but the Commission refused to act unless Coakley withdrew his suit against the Chicago club from court. The lawsuit was eventually settled privately.

In June, Coakley made one last attempt at a comeback with the New York Highlanders, but it failed miserably, likely because he hadn’t pitched a major league game in over two years. He allowed 13 runs (seven earned) and 20 hits in two appearances (11 2/3 innings). Coakley went back to semipro ball and never wore a big league uniform again. His lifetime totals: 58-59 with a 2.35 ERA, the latter (as of 2019) 16th all-time among players in the modern era.

Williams rehired Coakley for $1,000 for the 1912 season.98 When inclement weather again ruined their field before the season, he relocated team practices to New York City over Easter, arranging exhibitions, including against the New York Giants. Behind ace George “Iron” Davis, who would enjoy a four-year major league career with the Highlanders and Braves, the team responded by going 11-3. The following season, 1913, Williams went 11-4, including a May 27 victory to snap Yale’s 17-game winning streak.

Coakley’s connection to scouting helped three of his players in that three-year span — Davis, Jack Mills, and Bill Otis — sign major league contracts. Charles “Doc” Barrett, the scout who landed Davis and Otis for the Highlanders, was the trainer for both Williams and the Highlanders from 1910 to 1914. Barrett, who was from Worcester, crossed paths with Connie Mack (who came from nearby East Brookfield, Massachusetts) as early as 1907, if not before. Barrett became Columbia’s head athletic trainer in 1921 (while Coakley was coaching), and remained there until his death in 1954.99

Then Williams consolidated its baseball, basketball, and football programs under one coach, and Coakley was out.

Coakley had continued to play semipro after his flop with the Highlanders — including Paterson and Long Branch (New Jersey) in 1912. He received a shot with Jersey City of the Double-A International League in 1913 but went 3-8 for the perennially cellar-dwelling team.100 He also considered buying a ball club.101 However, his day job was working for an advertising agency. Just 31 years old, he was holding onto baseball by a thread.

Columbia University, which had gone through six coaches in eight years, was looking to be more competitive. On February 18, 1914, Columbia announced for the first time it was splitting the baseball coaching duties between two men, both of whom happened to be ex-major leaguers.102 With Billy Lush as head coach and Coakley handling pitchers and catchers, the Lions, who had graduated many of their stars from the previous season, finished 10-7.103

Coakley’s contract terminated on the last day of the season in early May.104 Less than two weeks later, Coakley and New York billiard king John Doyle purchased the failing Bloomfield franchise in the short-lived Class D Atlantic League105 and moved it to Asbury Park. In addition to co-owning the club, Coakley both pitched and managed. After playing its first 40 games on the road, the Sea Urchins opened to fanfare in their home park on July 2. But the league itself barely made it to the scheduled September 7 end of the season.106

Impressed with how Coakley had handled its pitchers, including ace Eddie Shea, the previous year, Columbia snapped up Coakley to be head baseball coach for the 1915 season.107 In 1916, he guided the team to a 17-1 record, with three of his players receiving offers to sign professional contracts (though only one, George Smith, actually went pro). With the exception the 1919 season, when Columbia tried to consolidate its athletic coaching staff, Coakley remained in charge of the Lions nine through 1951. For a detailed account of this period, which is beyond the scope of this biography, please refer to “Andy Coakley at Columbia.” Some choice excerpts are presented here.

Coakley took a laissez-faire approach to coaching. He made his expectations clear, but he preferred not to impose rigid restrictions on his players. He felt that the more rules he created, the more they would be broken.

John McCormack, who played for Coakley in 1937, said he “never heard Andy raise his voice or utter a foul word. He was always well dressed.

“He was on a first-name basis with his players,” McCormack continued. “When we spoke I was ‘Mac’, he was ‘Andy’. Since the players respected him even though we called him ‘Andy’, he had full control of the team.”108

The father-son relationships he fostered over the years with his players may have stemmed, in part, from his own longings as a parent. Coakley’s only child, Kathleen Gray Coakley, died at age 10 on February 27, 1921, after heading to Florida to recuperate from a long illness. He rarely spoke of her.109 Coaching was a part-time position for Coakley; his bread and butter for most of his career and thereafter was selling insurance for Mellor & Allen in Lower Manhattan, and for Providence Mutual, headquartered in Philadelphia.110 Other business pursuits, in the early days, included semipro ventures. In 1915, he had coached Easton in the Saturday-only Lehigh Valley League (likely pulled in by Mike Donlin, who coached rival Phillipsburg).111 Also in August of that year, he hurled a no-hitter for the semipro Degnon Grays against Gowanus F.C.112

As late as 1917 and 1918, Coakley was still pitching semipro ball with a club from the Bronx called the Kingsbridge Athletics. This team played at Dyckman Oval in the far northern reaches of Manhattan, close to where Columbia’s Baker Field would be built. It’s likely that Coakley was the first major leaguer to appear at the Oval.113

The best-known of Coakley’s players to reach the major leagues, of course, was Lou Gehrig. Coakley often receives a startling amount of credit for grooming Gehrig. Gehrig biographer Ray Robinson, who graduated from Columbia in 1941 and superficially knew Coakley, thought the praise was overblown. “You’d have to be blind not to realize the talent right in front of you,” he said.114 Nonetheless, Coakley helped Gehrig refine his natural “sureness of hand,” feeding him hundreds of ground balls to improve his slow timing and sluggish reflexes.115

Pitchers George Smith (class of 1916), who played for four National League teams from 1916 through 1923, and Art Smith (1928), who had a cup of coffee with the White Sox in 1932, also suited up for Coakley at Columbia.

Coakley’s success with Gehrig may have spurred the Pittsfield Hillies of the Double-A Eastern League to make him manager in the middle of 1924 after Billy Gilbert resigned.116 The last-place team, which featured future major league stars Mule Haas and Earl Webb, won 12 of their first 18 under their new manager. The Hillies finished fifth in the eight-team league, but Coakley did not return.

Reporters were referring to Columbia baseball as “the Coakleymen” pretty regularly by the 1930s. In 1933 and 1934, the team won back-to-back championships in the Eastern Intercollegiate League (EIL), the predecessor to the Ivy League.117 From 1934 through 1936, Coakley had four players sign professional contracts.118

That was notable, because Coakley claimed he generally discouraged players from going pro. He said, “The greatest satisfaction I have derived from coaching is to meet a boy who has played for me five or ten years after he’s left Columbia and have him tell me I helped him make a success of his job.”119

Still, he sometimes brought his major league friends in to help coach his players, including Chief Bender, Gabby Street, and Herb Thormahlen.120 According to McCormack, the Yankees gave Coakley a season pass.

By 1951, Coakley looked to be slowing down. Physically drained, he announced the season would be his last in early May.121 Two days later, when the Lions visited Worcester, Holy Cross hosted a “day” in his honor, presenting him with luggage and a desk set. Columbia finished the year 10-7. Overall, Coakley compiled a 315-296-11 record, with three EIL titles (and the 17-1 1916 squad, before the EIL’s existence).

“I leave college baseball with keen regret,” Coakley told the Sporting News that fall. “I leave it with fond memories, with recollections of great players at Columbia, with a feeling of having torn myself away from something very much a part of my life. However, the calendar shouts that I am nearing 69, after which it will be 70, and it is better that a younger coach pick up the task.”122

Over the next decade, Coakley devoted himself full-time to his insurance business, remaining a fairly visible presence in baseball circles, on hand for ceremonial events,123 for his baseball expertise,124 or perhaps just for a good story. He otherwise lived quietly with his wife in their First Avenue apartment in Manhattan, frequently visiting old friends, such as Pete Noonan in western Massachusetts, or dropping by Columbia every so often to take in a game.125

Around New Year’s 1963, Coakley suffered a stroke that confined him to a nursing facility, the Mary Manning Walsh Home on 59th Street in Manhattan. He died on September 27, 1963, at age 80.126

The Collegiate Baseball Hall of Fame recognized Coakley posthumously, enshrining him in 1969. In 1970, Columbia renamed its baseball diamond Andy Coakley Field; however, it was renamed in 2008 in honor of an alum who funded significant renovations. That fall, Coakley was inducted as part of Columbia’s second Athletic Hall of Fame class. Gehrig and Collins were among the first.

Coakley is interred under an adobe-colored brick slab engraved with only his name at Kensico Cemetery in Valhalla, New York. To his right are his daughter, Kathleen, and wife, Mattie (who died in 1971); behind that row are his in-laws, the Grays. On the other side of the cemetery rest the ashes of Coakley’s prize pupil, Gehrig, and Paul Krichell, the scout who signed him.

Acknowledgements

Statistics are courtesy of www.baseball-reference.com and www.retrosheet.org, unless otherwise noted.

The author would like to thank Jo-Anne Carr at the College of the Holy Cross archives; Columbia University for the general use of its library and archives while the author was a student in 2003; Linda Hall at the Williams College archives; Dr. Gerald Klingon and the late John McCormack for sharing their memories of playing for the Columbia baseball team; Norman Macht for sharing his research about the early Athletics; Nancy Miller at the University of Pennsylvania archives; Gabriel Schechter, formerly of the National Baseball Hall of Fame; the late Ray Robinson for his insight into Coakley and Gehrig; and all the other SABR members who offered me help and support.

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Norman Macht and fact-checked by Alan Cohen.

Notes

1 Death certificate in 1944 reads “Nellie Theresa Coakley,” but older census records refer to her as “Ellen R Coakley.” There may be some mix-up with an “Ellen Reardon,” a relative of Hannah Coakley, who is also buried in the family plot.

2 Perhaps short for Honora, as per birth record. Her death certificate reads “Nora Stanislan Coakley”; she died of Bright’s Disease on February 11, 1917, at 37.

3 Patrick T. Conley and Paul Campbell. South Providence. Arcadia, 2006. pp. 105-107.

4 John (“Jack”) Flynn, a year his junior, was one of Coakley’s sandlot teammates. He would follow Coakley to Holy Cross and play first base with the Pittsburgh Pirates and Washington Senators from 1910-1912 before coaching rival Providence College for ten years.

5 “R.I.’s Andy Coakley Dies at 81; Baseball Star, Discovered Gehrig.” Providence Journal. September 28, 1963.

6 Most sources state that Coakley went to “Providence High School.” They are not wrong; the first high school in Providence was renamed Providence Classical High School in 1898, right around the time Coakley would have been attending. Coakley’s obituary in the Providence Journal refers to it as “Classical,” as it is called today.

7 A Worcester writer that had initially called him “green on the inside points of the game” wrote after his first collegiate appearance that Coakley “gave evidence of having all the qualities of a successful pitcher, not a single one lacking.” “Andy Coakley, Coach of Columbia, To Be Honored Here on Saturday.” The Tomahawk. c.] May 4, 1951 (Holy Cross Archives).

8 The Alerts and Roses fielded full professional line-ups around the turn of the century, but several standout college players participated on those teams, including future Athletics ace Jack Coombs. The rules were not standardized (or well-enforced) as to what type of professionalism affected college eligibility back then, and many institutions were not sure how to penalize players, anyway, for keeping fit over the summer and earning a little money to finance their education. The pay wasn’t much for this particular league; by 1903 the Alerts’ total monthly payroll topped out at $715 — and that was considered too high to keep the team going. See “The Scandal of College Players and ‘Summer Ball.’” Middle Innings: A Documentary History of Baseball 1900-1948. Dean A. Sullivan, ed. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1998. pp. 19-22; Richard Papenhausen, Saint John: A Sporting Tradition 1785-1985. Neptune, 1985. pp. 125-127.

9 A sportswriter hailed the 1-0 masterpiece as “the most wonderful contest played on the Yale field in many years.” “Holy Cross Defeats Yale.” Chicago Tribune. April 27, 1902. Yale’s only rally came in the sixth, when they loaded the bases — then Coakley struck out two to get out of the inning.

10 When Coakley fell just short that day, 2-1, against a lineup that featured at least four future major leaguers, the Washington Post seemed astonished: “The great Coakley, the man who shut out both Yale and Harvard, the man who in nine games allowed but thirty-nine hits” had been defeated. “Holy Cross Defeated: Georgetown Wins Great Victory by Score of 2 to 1.” Washington Post. May 29, 1902.

11 Statistical totals courtesy of the above article from The Tomahawk, May 1951 (Holy Cross archives).

12 The Malone Farmer. May 21, 1902.

13 Probably better for Coakley in the long run, as the Potsdam team would fold before summer’s end.

14 “Harmonious Meeting: League Confirms Malone’s Claim To Coakley.” The Plattsburgh Sentinel. May 30, 1902.

15 Sporting Life. August 16, 1902.

16 John Kieran. “Sports of the Times: The Uncovering of McAllister”. New York Times. September 9, 1940.

17 In the summer of 1921, Lou Gehrig put his collegiate athletic eligibility at risk when he played a handful of games for Hartford of the Eastern League as “Lou Lewis.” Coakley helped to lure Gehrig back to Columbia after his cover was blown and to convince the administration to reduce his punishment to a one-year suspension.

18 Omaha Morning World Herald. September 18, 1902; Fort Wayne Journal-Gazette. September 18, 1902.

19 “He had everything that should be included in the repertoire of a first-class pitcher — speed, control and a choice and varied assortment of curves,” The Philadelphia Inquirer proclaimed the next day. Perhaps the first and the third were true, but hardly the second; Coakley walked three and hit two.

20 Berman, Fred. “Andy Coakley Relives Early Baseball Days.” Columbia Daily Spectator. March 26, 1947.

21 Spink, J. G. T. “Mack Star, College Coach and Business Man.” The Sporting News. October 24, 1951.

22 “Coakley Is Out: Holy Cross Pitcher A Professional.” The Lowell Sun. January 9, 1903. (Associated Press report) Coakley’s pleas may have been an embellishment; true, the A’s had lost consecutive doubleheaders at second-place St. Louis as August turned to September, but they’d won twelve of fourteen and were four games up when Coakley debuted.

23 “Holy Cross Surprised By Pennsy.: Northern Institution Had No Intimation That Penn Would Refuse To Play”. The Washington Times. January 24, 1903. In the fallout, at least one institution, the University of Pennsylvania, dropped Holy Cross from its athletic schedule. “Penn Disciplines Four Colleges For Lax Rules.” The Philadelphia Inquirer. January 23, 1903.

24 “Holy Cross Collegians Surprised by Pennsy.” The Washington Times, January 24, 1903.

25 Bridgeport Herald. May 10, 1903. Peculiarly, the paper made light of the fact that Coakley was concealing his true identity under a pseudonym, but never speculated why.

26 The Lowell Sun. February 1, 1904.

27 Sporting Life. March 26, 1904.

28 Grayson, Harry. “Andy Coakley Discovered Collins, Developed Lou Gehrig’s Swing.” The Fitchburg Sentinel. July 21, 1943 (syndicated).

29 Kieran, John. “Sports of the Times: The Uncovering of McAllister”. New York Times. September 9, 1940.

30 McGuane, George. “Boyhood Idol Passes Away.” The Lowell Sun. June 15, 1975.

31 “Early Visitor to Florida, Umpired for Millionaires,” The Sporting News, October 24, 1951. In the article, Coakley also recalls umpiring a game in Palm Beach for employees of two hotels: “Nobody was present as an onlooker who wasn’t a millionaire. And most of ‘em just stood along the sidelines very democratically, dishing out to me one of the worst ridings any umpire ever took…. I knew from that moment Florida’s baseball future was assured.”

32 Bromberg, Lester. “Andy Coakley Recalls Life of a Rookie 50 Years Ago.” New York World-Telegram and Sun. March 5, 1955.

33 Bromberg

34 “Coakley Recalls Player-Fan Riot Of 40 Years Ago Instigated By Waddell,” Columbia Daily Spectator, August 13, 1943.

35 Shoddy, inconsistent bookkeeping had originally credited Coakley with a 17-8 record in 1905, including a September 26 game against Detroit, where he was tagged with the loss for pitching poorly, despite reliever Jimmy Dygert allowing the losing runs in the tenth.

36 “Twenty Greatest Plays: Baseball Men Make Their Selection of Most Notable Achievements.” New York Times. December 31, 1911.

37 The Utica Observer-Dispatch. July 1, 1923.

38 Utica Daily Press. February 23, 1927. To read about Coakley reminiscing about his first major league hit, see “Baseball Happenings,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, December 25, 1909.

39 Scheuer, Stewart H. “Coakley Got Early Start On Road To Major League Pitching Career With A’s.” Columbia Spectator. July 27, 1943.

40 “Baseball Contest Off; The Crowd Was Too Small.” New York Times. October 12, 1905.

41 Coakley retold the story multiple times over the years to the press. For a particularly colorful example, see “Coakley Calls Rube Waddell The Most Colorful Of All Ball Players.” Columbia Spectator. August 6, 1943. For further analysis of the “straw hat incident,” see Steven A. King, “The Strangest Month in the Strange Career of Rube Waddell,” The National Pastime, 2013, https://sabr.org/research/strangest-month-strange-career-rube-waddell. King suggests that the entire incident may never have happened. The author finds no evidence that would corroborate or refute this claim.

42 “Pennant In Doubt”. The Sporting News. October 7, 1905.

43 Koelsch, William F.H. “Metropolis’ Men Are Now the Acknowledged Champions of the World.” Sporting Life. October 21, 1905.

44 Spink, J. G. T. “Mack Star, College Coach and Business Man”. The Sporting News. October 24, 1951.

45 The Sporting News. May 12, 1906. (As reprinted from the Philadelphia North American)

46 “Break Is Coming.” The Sporting News. July 21, 1906.

47 “Coakley A Benedict.” Boston Daily. July 18, 1906.

48 Sporting Life. September 22, 1906. Other major leaguers discovered by Coakley over the years included Sterling “Dutch” Stryker, “Violet Array for Giants,” New York Times, December 7, 1916, and Arthur “Skinny” Graham, “Laurier Club Meets Malden Tonight at Aiken Street,” The Lowell Sun, August 28, 1931. Minor league outfielder Arthur Carroll was also a Coakley discovery. “New Yankee Prospect,” New York Times. September 2, 1920.

49 Sporting Life. November 10, 1906.

50 “Coakley Will Try Dentistry.” Boston American. October 27, 1906. (University of Pennsylvania Archives)

51 “‘Andy’ Coakley For Reds.” Washington Post. December 13, 1906.

52 See personal correspondence, Coakley file, National Baseball Hall of Fame Archives.

53 A cartoon ran in the newspaper that spring titled “How Pitcher Coakley Keeps In Shape,” with his (very poor) likeness using all his might to pull someone’s tooth with giant pliers. “My arm will be stronger than ever,” it had him proclaiming. Eau Claire Sunday Leader. March 10, 1907.

54 Giants manager John McGraw claimed these dire reports were exaggerated. “Cincinnati Again Loses to Giants, Coakley Having a Bad Inning.” New York Times. June 19, 1907.

55 “Coakley’s Mind Is Not Affected When He Knocks a Luckless Batter Out.” Sporting Life. August 31, 1907.

56 Ritter, Lawrence. The Glory of Their Times. New York: Vintage Books, 1985. pp.189-191

57 Utica Saturday Globe. June 6, 1908.

58 Zuber, C. H. “Spitball Here To Stay, He Claims.” The Fort Wayne Journal-Gazette. August 25, 1907.

59 “Coakley’s Chirp: Will Defer Practice of Dentistry for Another Year.” Sporting Life. October 12, 1907.

60 Sporting Life. February 8, 1908.

61 Mulford, Ren Jr. “Redland Astir.” Sporting Life. March 28, 1908.

62 Coakley had also befriended several Giants over the years, including Mike Donlin and Mathewson, and would participate in billiard tournaments at John McGraw’s pool hall during the offseason. See, e.g., Bulger, Bozeman, “Coakley Got Nothing for Helping Cubs Win Pennant,” The Evening World, December 29, 1908; “Coakley Defeats Strang,” New York Times, January 1, 1909.

63 “Matty Saves Day for the Giants.” New York Daily Tribune. September 25, 1908.

64 The Giants and the Pittsburgh Pirates (98-56) finished tied for second place, one game behind the Cubs (99-55). If one or both of Coakley’s wins had been a loss, the Merkle game would have remained a tie, and the Giants would have taken the pennant by a half-game.

65 “World Series Echoes.” Sporting Life. October 31, 1908.

66 “Coakley Didn’t Get Extra Pay.” Washington Times. January 11, 1909.

67 “Chance Predicts Changes in Line=Up of Championship Cubs,” Washington Post, February 14, 1909.

68 Id; see also Chicago Tribune, February 8, 1909.

69 Murphy publicly announced he was in negotiations with Columbus of the American Association. A member of the Columbus club, however, called the deal “all hot fuzz.” “Bobby Quinn Wasn’t Wise.” Kansas City Star. March 6, 1909. (reprinted from the Columbus Dispatch)

70 Lardner, R.W. “Cub Recruits Out in Cold.” Chicago Tribune. April 9, 1909.

71 Coakley had reportedly been conditioning away from the team in Providence. “Coakley Hasn’t Signed Contract,” Philadelphia Inquirer, March 21, 1909.

72 See, e.g., “Eddie Craig Hit in Winning Form,” Trenton Evening Times, May 24, 1909.

73 “Gets ‘Cub’ Pitcher,” Middletown Times-Press, May 28, 1909.

74 “Coakley to Play in the Tri-State,” Washington Times, June 4, 1909.

75 “Coakley joins outlaws.” Wilkes-Barre Times Leader. May 28, 1909.

76 Chicago Tribune. June 3, 1909.

77 “Coakley, Former Cub Twirler, Now Manager,” Oakland Tribune, July 13, 1909.

78 “Coakley to Pitch for Manhattans,” New York Times, July 22, 1909.

79 “Manhattans vs. Colored Giants,” New York Times, July 30, 1909.

80 “Indoor Baseball Regaining Favor.” Middletown Daily Times-Press. January 30, 1911; Grayson, Harry. “Hal Chase Was Greatest Instinctive Ball Player.” Zanesville Signal. May 26, 1947. (NEA report)

81 New York Times. February 17, 1910.

82 “Spicy Sporting Table Talk.” The Post-Standard. December 16, 1909.

83 “Andy Coakley For Grays.” The Rochester Democrat and Chronicle. March 27, 1910.

84 Washington Times. June 8, 1910.

85 Fultz was also the head coach of the Columbia University baseball team in 1910 and 1911. Could Coakley have been so inspired, or was it sheer coincidence he wound up there a few years later?

86 Correspondence between William Grayson Jr. and August Hermann, June 15, 1910. Coakley file, National Baseball Hall of Fame archives.

87 Grayson-Herrmann correspondence

88 “Coakley’s Case.” Sporting Life. October 22, 1910.

89 “Coakley’s Case,”

90 Richter, Francis C. “Coakley’s Case.” Sporting Life. October 8, 1910.

91 Coakley appealed the suspension, unsuccessfully, and was allowed to stay with Elmira a few more days until the matter was decided against him. Pitching the second game of a doubleheader against Syracuse on September 7, Coakley faced future Hall of Fame pitcher Grover Cleveland Alexander, who was, interestingly, playing center field in place of an injured regular that day. Coakley was so impressed with Alexander that he wanted to wire Giants manager John McGraw about the prospect, but was told he was already under contract with the Phillies. See also Talbot, Gayle. “Baseball Scouts To Follow Teams on Trips South.” Winona Republican-Herald. February 17, 1938. (Associated Press report).

92 “Coakley Is Sore.” Auburn Citizen. September 26, 1910.

93 See, e.g., “Sporting Comment: There’ll Be No Ball Games the Coming Winter. But a Lot of Politics, And Perhaps an Organization of Players — Andy Coakley on John H. Farrell,” Auburn Citizen, September 28, 1910; Jackson, Joe S., “Sporting Facts and Fancies,” Washington Post, November 5, 1912; “Showing Teeth: Already Is the New Ball Players’ Fraternity,” Sporting Life, November 16, 1912.

94 One of Coakley’s finds, Daniel Mahoney, a shortstop of Holy Cross who played just one game with the Cincinnati Reds, became yet another player to have his collegiate eligibility revoked when he signed a professional contract. See correspondence between Andy Coakley and August Hermann between 1911 and 1913. Coakley file, National Baseball Hall of Fame archives.

95 “Temporary Baseball Coach,” Williams Record, February 6, 1911; Notes, Williams Alumni Athletic Association, Vol. 3, p. 53 AC #33, March 18, 1911 (courtesy of Williams College archives).

96 Sanborn, I.E. “Aid for Suspended Players.” Chicago Tribune. February 5, 1911.

97 “So another case of insubordination ends with submission of the offender to the necessary discipline of ‘organized ball,’” wrote Sporting Life (April 22, 1911) — though it did not elaborate on specifics of said offender’s (Coakley’s) “submission.”

98 Williams also hired Coakley at that salary for 1913. Notes, Williams Alumni Athletic Association, Vol. 3, p. 53 AC #33, October 7, 1911 & December 16, 1912 (courtesy of Williams College archives).

99 Rory Costello, “Doc Barrett,” SABR BioProject (https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/cf82a4bf)

100 Coakley’s ERA was not available, but one has to believe that the 72 runs he allowed in 94 1/3 innings (6.89 runs per nine innings) could not all have been blamed on poor defense. Then again, Jersey City did finish 53‑101.

101 “Giants Want Romanach.” New York Times. December 18, 1913.

102 “Major League Stars Will Coach Varsity,” Columbia Spectator, February 18, 1914.

103 One of the players who went out for that 1914 squad was the son of Hall of Famer Ned Hanlon, who according to one account, couldn’t bunt. “It’s a good thing your ‘dad’ didn’t see that,” said Coakley. The younger Hanlon retorted, “If I don’t know how to do it better when he sees me, you’re not much of a coach.” Sportsman, “Live Tips and Topics,” Boston Daily Globe, March 14, 1914.

104 “Coakley’s Last Day At Columbia.” New York Times. May 2, 1914. The Times said the Columbia athletic department would have liked to retain him longer, but that Coakley’s other “business interests” got in the way.

105 “Bloomfield Club Is Rescued for League.” Middletown Daily Times-Press. May 14, 1914.

106 During a league meeting on August 11, a proposal to curtail the season at week’s end was voted down, 5-4.

107 According to Sporting Life on December 5, 1914, Columbia athletics manager Grant Stone chose Coakley “after weeks of dickering with Billy Lush.”

108 Correspondence between John McCormack and the author, March 15, 2008.

109 “Coakley Cancels Baseball Smoker,” Columbia Daily Spectator, March 1, 1921. Jerry Klingon, who played for Columbia in the 1930’s, was not aware Coakley had any children when this author interviewed him.

110 One of Coakley’s clients was US Open champion golfer Gene Sarazen. “Gene Insured,” The Circleville (Ohio) Herald, July 7, 1932.

111 “Andy Coakley Coaching Pros,” Columbia Spectator, July 15, 1915; “Donlin in a League of $90-A-Month Men,” Reno Evening Gazette, July 21,1915.

112 Miller, Morris. “Sport Snap Shots.” The Janesville Daily Gazette, August 28, 1915. Coakley didn’t hesitate to show he could still pitch well enough as a young coach, as evidenced by his shutting out his own players for two innings during a scrimmage in 1918. “Coakley’s Pets in Trim for Maroon,” Columbia Daily Spectator, April 9, 1918.

113 Rory Costello, “Dyckman Oval,” SABR Ballparks Project (https://sabr.org/node/50705)

114 Telephone interview with Ray Robinson, July 12, 2017.

115 “Coakley Recalls Lou Gehrig South Field Slugging Days,” Columbia Daily Spectator, August 20, 1943.

116 “Sport Sparks,” New Castle News, August 22, 1924. As Gehrig spent almost the full season with the Hartford Senators that year, Coakley got to manage against him — and Gehrig took his pitchers deep twice in one game. “Gehrig Bats Two Home Runs As Champions Win Twice Over Andy Coakley’s Team,” Bridgeport Telegram, August 14, 1924.

117 Formed in 1930, the EIL was originally comprised of Columbia, Yale, Princeton, Cornell, Penn, and Dartmouth. Harvard joined in 1934, and Brown, Army, and Navy in 1948. The EIL remained a collegiate baseball mainstay until 1992, when the Ivy League (1954) which had previously functioned only informally as a college baseball league, absorbed the eight teams that weren’t Army and Navy.

118 The four players were pitcher Ray White (captain of the 1933 team); first baseman Owen McDowell (captain of the 1934 team); catcher Ed Brominski (the 1935 captain); and outfielder Al Barabas (1936).

119 Coakley, Andy. “Hugh Bradley Says: Veteran Coach Says Leagues Helped to Build Up Following,” New York Evening Post, May 12, 1936. Unclear whether these were Coakley’s words or those of a ghostwriter.

120 Coakley actually had a little fun with a reporter the year Thormahlen helped out. The reporter was impressed by a particular lefthander warming up on the mound for Columbia and asked who it was. “Does he look good to you?” Coakley said, and the writer complimented his “motions and the assurance with which he carried himself.” At which point Coakley revealed it was ex-major leaguer Thormahlen. “Funny how you can tell a player when you see one even walk on a field.” Kelley, Robert F., “The Amateur Sportsman,” New York Evening Post, March 23, 1925.

121 Freyberg, Mike. “Coakley to Retire,” Columbia Daily Spectator, May 3, 1951.

122 Spink, J.G.T., “Mack Star, College Coach and Business Man,” The Sporting News, October 24, 1951.

123 See, e.g., Photo captioned “At Opening of baseball Exhibit in Museum Here,” New York Times, April 30, 1952; “Big Leaguer Stars to Share Spotlight at Journal-American Victory Banquet,” Sporting News, October 13, 1954.

124 See, e.g., “Caught on the Fly: Picking Hearst Sandlot Teams,” Sporting News, July 30, 1952 (selecting a sandlot all-star team); “Heat Treatment May Cause Sore Arms, Coakley Claims,” Sporting News, May 1, 1957; “Sisler, Cooper Compare Pitchers’ Notes,” Sporting News, May 8, 1957 (commenting on the effect of the “lively ball” and “too much reliance on the bull pen”).

125 “N. Y. U. Subdues Columbia as Gherardi Excels in Relief Role at Baker Field,” New York Times, April 4, 1958.

126 At Coakley’s passing, there were just two surviving players from the 1905 Athletics: John Knight and Bris Lord.

Full Name

Andrew James Coakley

Born

November 20, 1882 at Providence, RI (USA)

Died

September 27, 1963 at New York, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.