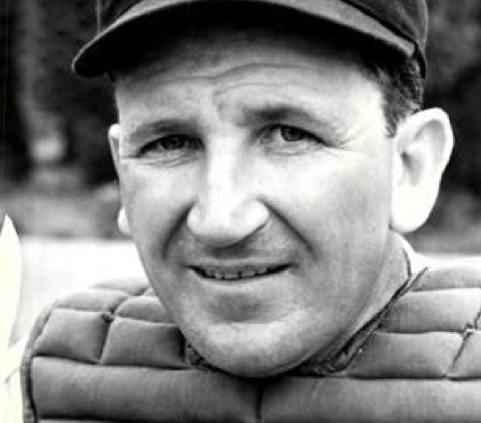

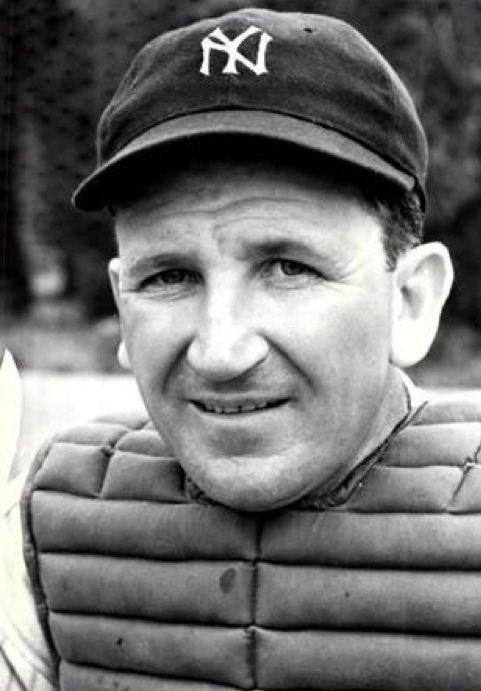

Arndt Jorgens

Joe DiMaggio put his name on a book titled Lucky to Be a Yankee. His teammate Arndt Jorgens seconded the emotion. In 10 years as a backup catcher behind Hall of Famer Bill Dickey, Jorgens cashed five World Series checks totaling around $30,000 without appearing in a single Series game.

Joe DiMaggio put his name on a book titled Lucky to Be a Yankee. His teammate Arndt Jorgens seconded the emotion. In 10 years as a backup catcher behind Hall of Famer Bill Dickey, Jorgens cashed five World Series checks totaling around $30,000 without appearing in a single Series game.

As the Yankees’ second- or third-string catcher, he started as many as 50 games in only one season. Sportswriters poked fun at his supposedly soft life. New York Daily News columnist Jimmy Powers gibed, “10-1 the guy has more splinters in his fanny than Pinocchio.” The same paper ran his picture with the caption, “A rare photo — he’s working.”1

His main duties included warming up pitchers, cheerleading from the bench, and occasionally relieving Dickey in the late innings or in the second game of a doubleheader. “Jorgens was just a fair hitter, a grand receiver and a remarkable guy who stuck around the Yanks for several years as insurance,” Dan Daniel wrote.2 He stuck around because his “enthusiasm and pep” made him a favorite of manager Joe McCarthy.3 His top salary of $7,500 was a not-so-small fortune during the Depression, when up to one-fourth of workers had no job. It’s equivalent to about $137,000 in 2020 dollars, according to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics.

“When other players yell at me, ‘You lucky stiff,’” Jorgens said, “I can’t do anything else but smile back.”4

Arndt Ludvig Jørgensen was born on May 18, 1905, in Åmot, Modum kommune, Norway, a postcard village in a landscape of forests, lakes, and river valleys whose beauty enchanted some of the nation’s leading painters. Baseball-reference.com lists him as the last of three Norwegian-born major leaguers.

Soon after Arndt’s birth, his father, Andreas Jørgensen, left his family and his job as a railroad fireman to emigrate and join his own mother in Rockford, Illinois. Andreas’s wife, Helma (Larsen), a cook, followed with their son two years later, in 1907. The family moved to Chicago, where Andreas worked with a brother in a furniture-making business. The Jørgensens shortened their last name, and the parents anglicized their given names to Andrew and Helen. Arndt was called “Art” on several baseball cards, but there’s no evidence that he used that name.5 He eventually became an American citizen.

In Illinois the family grew to include another son and a daughter. Befitting a Norwegian, the father was an avid skier, but his sons preferred the American game, baseball. Arndt’s brother, Orville, a pitcher three years younger, followed him to the majors, fashioning a three-year career at the opposite end of the standings with the Philadelphia Phillies.

Arndt discovered the game when he was about 6 and couldn’t remember playing any position except catcher.6 He became a star for Lane Technical High School in Chicago. When he was a freshman in 1920, the team played a highly publicized game against the New York City champions from Commerce High led by “the ‘Babe Ruth’ of the high schools,” Louis Gherig (as some newspapers spelled it). Jorgens didn’t appear in the game, but he saw Gehrig wallop a towering ninth-inning grand slam out of Cubs Park, the future Wrigley Field.7

With Jorgens catching, Lane Tech won an unofficial national prep championship in 1923. After graduation, he was working with his father and uncle in the furniture factory when major leaguers Johnny Mostil and Freddie Lindstrom saw him playing for the semipro Rogers Park team and recommended him to the Rock Island, Illinois, club of the Class-D Mississippi Valley League. Jorgens was not yet 21. It took him several months to persuade his father to sign a contract for him.8

After hitting .302 for Rock Island in 1926, Jorgens jumped up to Class-A ball at Oklahoma City. In his second season there, he batted .335, and scout Eddie Herr bought him for the Yankees. “I think I’ve sent [manager Miller] Huggins a real coming catcher,” Herr said. “He’s a little fellow, like [Ray] Schalk and [Muddy] Ruel, but he’s built of iron. … He hits the ball, too; he’s a sweet right-handed hitter.”9

Jorgens stood 5-foot-9 and weighed around 160 pounds when he reported to the Yankees for spring training in 1929. Writer Will Wedge called him “a redhead, or almost.”10 Towering over him was another rookie catcher, Bill Dickey, at 6-foot-1. Although the Murderers Row lineup powered by Ruth and Gehrig had won three straight pennants, catching was their weakest spot. Dickey claimed the regular job, and Jorgens earned a place on the roster with two spring training homers.

On Opening Day the Yankees took the field with a new look: numbers on the backs of their uniforms. The numbers were assigned according to batting-order positions; that’s how Ruth became No. 3 and Gehrig 4. Pitchers and substitutes got double digits. Jorgens wore 32, the highest on the team,11 illustrating his precarious status. After a month he was sent down to Double-A Jersey City, where he stayed until a September recall. It was the same story in 1930, but in his two brief trials with the big club he lived up to his billing as a sweet hitter, batting .324 and .367.

Jorgens stuck with the Yankees in 1931 and stuck to the bench permanently. For the next decade, Dickey caught more than 100 games every year. Six other catchers wore pinstripes, from rookies to decorated veterans, but none could push Jorgens off the roster.

In 1932 he hit the first two home runs of his career. The first, on June 1 at Philadelphia off the Athletics’ lefty Rube Walberg, gave the Yankees a lead, but they lost the game.

On July 4 Dickey slugged Washington outfielder Carl Reynolds after a collision at the plate. The punch broke Reynolds’s jaw and cost the Yankees catcher a 30-day suspension. Presented with his first opportunity for extensive playing time, Jorgens failed to take advantage. He hit .169 with a .446 OPS in 26 games while Dickey was sidelined, though he did collect his second homer on July 11 against the Browns.

In a career with few highlights, Jorgens enjoyed his most memorable day at the plate on June 10, 1933. In the second game of a doubleheader, he delivered a first-inning grand slam off the Athletics’ right-hander Sugar Cain to extend New York’s lead to 5-0. When he came up in the sixth, the A’s had tied the score. This time he touched Cain for a two-run shot into Shibe Park’s upper deck in left field, but the Yankees blew the lead and lost. Those were the last homers of Jorgens’s career.

Another injury — a foul tip that broke a bone in Dickey’s throwing hand in 1934 — gave Jorgens another chance to play every day, but he flopped again: a .479 OPS while filling in for 35 games. He appeared in a major-league career-high 58 games that year.

His strong arm was the key to a wild finish at Comiskey Park on September 6 when the Yankees’ Red Ruffing took a 5-2 lead over the White Sox into the bottom of the ninth. Consecutive singles by Luke Appling, Jimmy Dykes, and Marty Hopkins made it 5-3 and brought the potential winning run to the plate with two men on. After McCarthy called in Johnny Murphy to save the game, Jorgens picked Dykes off second for the first out. As Murphy threw strike three past pinch-hitter Charlie Uhlir, Jorgens cut down Hopkins trying to steal second for a double play to end the game. Thanks to his catcher, Murphy was credited with getting three outs while facing one batter.12

In 1936 Jorgens dropped to third string with Joe Glenn taking over as the primary backup for the next three years. Glenn, born Joseph Guzenski, was a refugee from the Pennsylvania coal country who had come up through the Yankees farm system. He proved to be a much better hitter, but he never got into a World Series game, either.

With Glenn’s emergence, Jorgens was occasionally mentioned as trade bait, but no other team was interested. He was past 30, his batting average usually wallowed in the low .200s, and he hadn’t hit a home run since 1933.

He held on to his roster spot even as his playing time dwindled “because McCarthy loved his attitude,” said outfielder Tommy Henrich, who joined the club in 1937.13 Jorgens was a pleasant fellow and a family man. He had married a Chicago-area woman, Madelyn Schultz, and they had a daughter, Barbara.14 He was popular with teammates; before Gehrig married, he sometimes went to dinner with the Jorgens couple and danced with Madelyn.15 Club president Ed Barrow described Jorgens as “one of the nicest men ever to play for the Yankees.”16

He also had a hard edge. Henrich said the benchwarmer served as an enforcer of McCarthy’s winning code. “His position as a third-stringer didn’t make any difference, either,” Henrich recalled. “He’d yell at us first-stringers anyhow. He saw me clowning in the dugout before a game in my rookie year and he let me have it. ‘C’mon Tom, bear down!’ And I did.”17

Glenn was traded after the 1938 season to make way for a minor-league phenom, 23-year-old Buddy Rosar. Rosar had won the International League batting title, hitting .387 for Newark, and looked like the heir apparent to Dickey, who was now 32.

While the Yankees won four straight World Series championships from 1936 through 1939, Jorgens all but disappeared. He got into 31 games in 1936, then 13, then 9, and only 3 in ’39. His biggest game was one that didn’t count: the first Hall of Fame game on opening day of the museum in Cooperstown, New York, on June 12, 1939.

The majors took that Monday off and each of the 16 teams sent two players for an exhibition in the remote hamlet where baseball was allegedly born 100 years earlier. Some teams sent their stars — Grove, Greenberg, Gehringer, Hubbell, Ott, and Dizzy Dean were there, among others. The Yankees’ McCarthy dispatched his regular left fielder, George Selkirk, and Jorgens. It may have been the manager’s reward for one of his favorites, or McCarthy may have just sent his most expendable man to the meaningless casual game.

In the fifth inning, Jorgens was behind the plate when the newly enshrined Babe Ruth thrilled the crowd by stepping up as a pinch hitter. With the spectators clamoring for a long ball, the 44-year-old Ruth lifted a meek pop foul. As Jorgens settled under it, fans yelled “Drop it! Drop it!” But Jorgens was a Yankee, not a clown. He squeezed the ball in his mitt to retire his former teammate and disappoint the crowd.18

Jorgens appeared in his first official game of 1939 in Boston on May 30, when he pinch-ran for Joe DiMaggio, who had a sore leg. He caught the final inning of a game in June. By August 2 he hadn’t played for six weeks. With the Yankees trailing Detroit at the Stadium in the Bronx, Jorgens replaced Dickey in the top of the ninth, catching Spud Chandler. It was his 307th, and last, major-league appearance. He didn’t come to bat all year. But he collected his fifth World Series check.

He stayed on the roster for the entire 1940 season without playing a single inning. At 35, he announced his retirement in November. “I’ll miss the Yanks, the fans and the Stadium,” he wrote to President Barrow. “But I want to get into business and here’s my chance.”19

His life after baseball was busier and more successful. He went to work for his father-in-law, Louis F. Schultz, in the family-owned Schultz Bros. variety-store chain based in Chicago. Jorgens rose to be president of the company in the 1960s, when Schultz Bros. was at its peak with more than 70 stores in five Midwestern states. After he retired, the stores, downtown fixtures in many small communities, were crushed by Walmart, and Schultz Bros. liquidated in bankruptcy.

Jorgens died of a heart attack at 74 on March 1, 1980, at his home in Wilmette, Illinois. “I certainly am not the game’s greatest catcher, or the greatest hitter,” he said near the end of his baseball career, “so perhaps I am the luckiest ballplayer.”20

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Norman Macht, and fact-checked by Chris Rainey.

Notes

1 Jimmy Powers, “The Power House,” New York Daily News, November 14, 1940: 64; “Jorgens Ends Sit-Down,” Daily News, November 14, 1940: 65.

2 Dan Daniel, “Over the Fence,” The Sporting News (hereafter TSN), October 28, 1943: 8.

3 “Peps Up the Yankees,” TSN, July 1, 1932:1.

4 Frederick G. Lieb, “Jackpots Shower on Jorgens in Bullpen for Yankees,” TSN, September 7, 1939: 3.

5 Erlend Grinna Forsdahl, “From Modum to the Yankees,” Dagbladet Sportsmagasinet, January 2, 2009. Forsdahl’s translation from Norwegian to English is in Jorgens’ file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame library, Cooperstown, New York. The names Andrew, Helen, and Arndt Jorgens appear in the 1930 US census.

6 Arndt Jorgens, “Here’s How I Broke In,” unidentified clipping in HOF file.

7 James Crusinberry, “New York Preps Down Lane Tech in Hitfest, 12-6,” Chicago Tribune, June 27, 1920: 17.

8 “Islander Club Signs Prize Chicago Catcher,” Rock Island (Illinois) Argus, February 26, 1926: 15.

9 Lieb.

10 Will Wedge, “Jorgens Hits Fence Topper,” New York Sun, April 5, 1929, in Jorgens’ HOF file.

11 Thanks to Lyle Spatz for this information.

12 Matt Ferenchick, “The story of a crazy White Sox-Yankees game ending from 1934,” pinstripealley.com, December 17, 2016, https://www.pinstripealley.com/2016/12/17/13988262/yankees-history-white-sox-johnny-murphy-tony-lazzeri-joe-mccarthy.

13 Tommy Henrich with Bill Gilbert, Five O’Clock Lightning (New York: Birch Lane, 1992), quoted in Rob Neyer, Baseball Dynasties (New York: W.W. Norton, 2000), 145.

14 Some sources spell Mrs. Jorgens’ name “Madeline,” but it is “Madelyn” on a questionnaire Arndt Jorgens filled out in 1963, in his HOF file.

15 Forsdahl.

16 “Sitting Bullpenner Goes to Work,” New York Daily News, November 14, 1940: 65.

17 Henrich.

18 Jim Reisler, A Great Day in Cooperstown (New York: Carroll & Graf, 2006), 198-200.

19 “Sitting Bullpenner Goes to Work.”

20 Lieb.

Full Name

Arndt Ludwig Jorgens

Born

May 18, 1905 at Modum, (Norway)

Died

March 1, 1980 at Evanston, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.