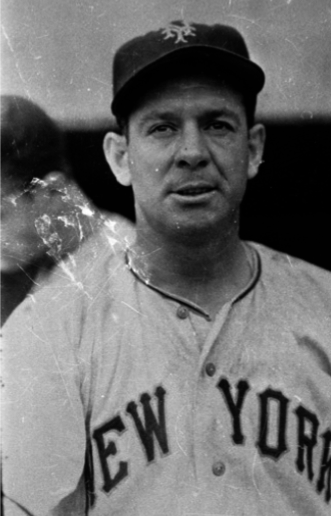

Augie Galan

Donning the uniforms of the Chicago Cubs and Brooklyn Dodgers for the better part of his career, along with playing short stints for the Reds, Giants, and Athletics, Augie Galan (pronounced “guh-LANN”) put together a lifetime .287 batting average in 16 major-league seasons. He reached the .300 plateau six times, played in three World Series, and was named to three All-Star squads.

Donning the uniforms of the Chicago Cubs and Brooklyn Dodgers for the better part of his career, along with playing short stints for the Reds, Giants, and Athletics, Augie Galan (pronounced “guh-LANN”) put together a lifetime .287 batting average in 16 major-league seasons. He reached the .300 plateau six times, played in three World Series, and was named to three All-Star squads.

August John Galan was born in Berkeley, California, on May 25, 1912. Galan’s parents had emigrated from France in the late 19th century, and his father operated a French hand laundry on Berkeley’s University Avenue. One of eight children, Augie maintained that he would have otherwise been involved in the family business had baseball not become his profession. “If something happened to take me out of baseball, I could make a living in the laundry business. I started working for my father after school hours when I was 12 years old and know every branch of the business,” he once said.1

It was baseball, however, that drew his early interest, and it was on the local sandlots of the East Bay, especially James Kenney Park, that Galan honed his skills. At about the age of 11, he broke his right elbow when he fell out of a tree. He concealed the extent of his injury, and because he didn’t see a physician, the arm healed improperly. As a result, he learned to bat left-handed, a skill that served him well in later years.2

After graduation from Berkeley High, where he starred, Galan signed with the San Francisco Seals of the Pacific Coast League in 1931. He was sent to a Class D farm team at Globe in the Arizona-Texas League and the next season was brought up to the Seals camp, where he won the starting shortstop spot and hit a respectable .291. Near season’s end, Galan, whose heritage led to him to be called Frenchy during his PCL days, requested permission to join a Seals teammate, Hawaiian-born Prince Oana, on a barnstorming trip back to the islands. With three games left in the season, Vince DiMaggio persuaded Seals manager Ike Caveney to allow his little brother Joe to take over at shortstop while Galan was in Hawaii.3

The following season, 1933, Joe took an outfield spot with the Seals, where he batted for a lofty .340 average; only Galan, the cleanup hitter, topped DiMaggio and, in fact, carried the highest average on the team, .356. He led the PCL in runs scored (164) and triples (22); he also swiped 41 bases.

A New York Yankees scout approached Galan after hearing rumors that there might be something wrong with the ballplayer’s right arm, and asked to see it. Galan refused. “Well, I was dead either way,” he said years later. “So I decided not to remove my coat, and maybe it wouldn’t get around and somebody else would take a chance on me.” The Chicago Cubs indeed took notice of Galan’s fine season and obtained him from San Francisco for $25,000 and seven veteran players.4

During the 1934 season, Galan platooned for the Cubs at second base, hitting .260 in 192 at-bats. He quickly earned the name “Goo Goo” from his teammates, due to his “great big round eyes,” an endearing moniker that survived throughout his playing career. Second base proved to be a bit of a defensive challenge for the rookie, however, and the following year Cubs manager Charlie Grimm moved Galan to the outfield to take advantage of his speed.5

The Cubs’ first baseman in 1935, Phil Cavarretta, looked back on that season many years later. “Augie Galan originally was a second baseman, but we had Billy Herman, so Charlie moved him out to center field, because we needed a center fielder, and Augie turned out to be one of the best fielding center fielders I’ve ever seen. He had a great arm, and he was a good little hitter. He was our leadoff man. Billy Herman was hitting second, and I’m not just saying this just because they were my teammates, but as far as hit-and-run men are concerned, to me Augie Galan and Billy Herman were the best.”6

The move from second to the outfield paid immediate dividends. In his sophomore year, one in which the Cubs claimed the National League pennant, the switch-hitting Galan hit .314, collected 203 hits, and led the league in both runs scored (133) and stolen bases (22). Galan played the full 154-game schedule (646 at-bats) without hitting into a double play, the first player ever to accomplish the feat. Ironically, however, in an extra-inning affair against the Reds at Wrigley Field on April 21, Galan did line into a triple play.7

The 1935 World Series, however, did not end well for Galan, who hit .160 (4-for-25), or, for that matter, for the Cubs. The Detroit Tigers took the fall classic in six games.

As players gathered for spring training in 1936, one reporter considered what Galan meant to the Cubs. “In addition to his value as a ballplayer, Augie was good medicine for the team’s morale with his pleasing personality and his infectious smile,” the scribe noted. “He went over big with the fans in every city he visited.”8

“Augie Galan was always happy,” remembered Cavarretta. Billy Herman characterized Galan by saying, “He loved to laugh and fool around, and he had a great imagination for practical jokes. His favorite victim was [Chuck] Klein.”9

On the heels of his tremendous 1935 season, Galan was named to start the All-Star Game in 1936 at Boston’s Braves Field. In the fifth inning, he hit the first All-Star home run ever by a Cub, driving a pitch from Detroit’s Schoolboy Rowe off the right-field foul pole. But the 1936 and ’37 seasons proved disappointing to Galan, who saw his batting average dip to .264 and .252, respectively, though in 1937 the outfielder did hit 18 home runs and his 23 stolen bases led the league. One game in this period stands out. On June 25, 1937, against the Dodgers, Galan accomplished a feat never before witnessed in the National League, and only once before in baseball. He launched home runs from both sides of the plate in the same game: from the left side against Freddie Fitzsimmons and from the right side off Ralph Birkofer; only Wally Schang of the Philadelphia Athletics had accomplished it previously, in 1916.10

Galan bounced back in 1938, lifting his average to .286, and he was once again named an All-Star. After looking up in the standings to see the Giants claim first place in 1936 and 1937, the Cubs again hoisted the National League pennant at Wrigley Field in 1938, only to have the Yankees sweep the World Series in four games. Galan saw limited duty due to a knee injury sustained late in the season and went 0-for-2 as a pinch-hitter in the Series.11

Galan remained an everyday outfielder for the Cubs and his batting average improved to .304 in 1939, despite his having to play with an ailing knee at the start of the season. Sportswriter Frank Moran characterized Galan as the National League equivalent of the “Iron Horse,” in July 1939, with “two twisted knees” and “performing with his leg in a steel brace and his right elbow swollen nearly twice its original size.” However, much like the Dodgers’ Pete Reiser, Galan did not know how to play with less than full intensity, and he often paid the price. Perhaps the worst injury came in late July 1940, when Galan broke a knee crashing into the outfield wall at Shibe Park. He saw limited duty from then on with the Cubs and some within the front office felt the outfielder’s career was just about through. While rehabbing his ailing knees in 1941, Galan was good-naturedly outfitted by the team’s trainer with a jockey’s cap and a whip for riding the stationary bike in the clubhouse. Galan was known to be a big fan of horse racing, and often carried a racing form under his arms. But he could not hide his general discontent. The Cubs had recently dealt away two of his best buddies on the ballclub, Billy Herman to the Dodgers and Billy Jurges to the Giants. Couple this with his frustrating injury, and the usually good-natured Galan was not happy.12

In August 1941, with Galan hitting just .208 in 65 games, the Cubs elected to sell his contract to the Los Angeles Angels of the PCL. Galan refused to go. Instead the Brooklyn Dodgers picked up his contract in exchange for $2,500 and pitcher Mace Brown. According to Brooklyn pitcher Rex Barney, Billy Herman persuaded Dodgers owner Larry MacPhail to take a chance on the oft-injured Galan. He arrived in Brooklyn at the tail end of August, made a spectacular diving catch in center in his first game as a Dodger, and reinjured his knee in the process. Still, he helped Brooklyn win its first pennant since 1920. He was hitless in two World Series at-bats against the Yankees, but the Dodgers liked what they saw and Galan remained with the team for another five seasons, through 1946.13

Slated to become a regular in 1942, Galan was stricken with typhoid fever and saw action in only 69 games. He became an everyday player again with the Dodgers in 1943, and over a four-season span hit between .307 and .318. He was selected to be on the All-Star squad in 1943 and 1944; later in ’44, he established a Dodger franchise record, later matched by Roy Campanella and Matt Kemp, by driving in a run in nine consecutive games. Rex Barney recounted in his memoirs, “Galan was as selective a hitter as Ted Williams. He swung only at strikes. Even in batting practice, he made the pitchers throw strikes.” In fact, with his discerning eye and great patience, Galan twice led the National League in walks during this period (1943 and 1944).14

If Galan had his way, however, he would have put his bat and glove aside and joined many of his colleagues in the military service during World War II. But after a physical following the 1942 season, the Selective Service declared him 4-F, unfit for military service, not only due to his baseball-induced knee injuries, but also because of the arm problem caused by his early boyhood tree mishap. Indeed, he was required to freeze his arm before every game. Galan once explained, “By the sixth or seventh inning, the feeling would come back, and if I had to make a throw it would be like somebody sticking needles in me.”15

Though he hit a robust .310 with the Dodgers in 1946, Galan was traded to the Cincinnati Reds for pitcher Ed Heusser after the season. Brooklyn Eagle sportswriter Tommy Holmes wrote that “the deal … does not meet with the unqualified approval of Brooklyn fans. Galan, a grand fellow and a conscientious, capable ball player, is deservedly popular here.” The columnist speculated that it was just another instance of Branch Rickey trading or selling a veteran while he still had market value. As a matter of fact, the Dodgers had a surplus of outfielders heading into the 1947 season, including Dixie Walker, Gene Hermanski, Pete Reiser, Carl Furillo, and a young prospect named Duke Snider.16

Showing he could still swing the bat, Galan posted a .314 average with Cincinnati in 124 games in 1947 and led the league with a .449 on-base percentage. But his big-league career was clearly winding down, his many knee injuries taking a toll and limiting his playing time. Galan had but 165 plate appearances in his final two seasons, playing with the Reds, New York Giants, and Philadelphia A’s. Over a span of 16 seasons, Galan had played every position in the majors except for pitcher and catcher, and had hit for a .287 average, collecting 1,706 hits and amassing an even 100 home runs. His favorite target for home runs had been Bucky Walters, whom he took deep five times.17

Galan returned home to the Bay Area and signed with the Oakland Oaks of the PCL. He played first base, third base, and the outfield in 265 games over the 1950 and 1951 seasons, and was a coach for the team in 1952. He took over as manager in 1953, succeeding Mel Ott; the team played poorly, however, and finished seventh, and Galan was fired after just a year at the helm. At the end of the year, he married Shirley Boyle. He accepted a coaching job with the Philadelphia Athletics in 1954. Player-manager Eddie Joost found Galan to be “knowledgeable, and a good guy, and helpful.”18

But coaching for a last-place team some 3,000 miles from his home and his new bride was not appealing, and after one year in Philadelphia, Galan retired from the game for good. He returned to the Bay Area to manage a string of butcher shops, a business he had begun during his playing days. Together Augie and Shirley raised four children. On December 28, 1993, one day after their 40th wedding anniversary, Galan died at the age of 81.19

This biography originally appeared in “Van Lingle Mungo: The Man, The Song, The Players” (SABR, 2014), edited by Bill Nowlin.

Notes

1 Doug Feldman, September Streak: The 1935 Chicago Cubs Chase the Pennant (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Co., 2003), 29. While a few sources list Galan’s birth date as May 23, most sources, ranging from the Sporting News’ Baseball Register (1945 edition) to MLB.com and the US Social Security Death Index cite May 25.

2 For most of his playing years, Galan was identified as being a switch-hitter. Bob McConnell wrote “Searching Out the Switch Hitters” in the 1973 edition of SABR’s Baseball Research Journal, Galan, from the start of his major-league career in 1934 through 1940, batted from both sides of the plate. However, he batted only right-handed in 1941, went back to being a switch-hitter from 1942 through 1944, and then batted only left-handed from 1945 through the end of his career in 1949. McConnell said he sent letters to living ballplayers for his research and Galan wrote back that he was a switch-hitter until 1943, when he began batting exclusively left-handed. Yet, reports in the Brooklyn Eagle cite at least a couple of exceptions: “Augie Galan went back to switch-hitting, batting right-handed against southpaw Max Lanier. It was on instructions from manager Leo Durocher” (May 13, 1944). A July 31, 1944, article in the Eagle stated that Galan had switched sides of the plate in the same at-bat after failing to get down a sacrifice bunt after two strikes in the previous day’s game.

3 Kevin Nelson, The Golden Game: The Story of California Baseball (Berkeley, California: Heyday Books, 2004), 177.

4 Pete Cava, Tales from the Cubs Dugout (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing, 2000), 94; Spalding, 98. The players he was traded for were pitchers Sam Gibson, Win Ballou, Leroy Hermann, and Walter Mails; catchers Larry Woodall and Hugh McMullen; and infielder Lenny Backer.

5 Rex Barney with Norman L. Macht, Rex Barney’s Thank Youuuu (Centreville, Maryland: Tidewater Publishers, 1993), 42; References to “Goo-Goo” Galan appear in wire-service stories over the years, including the Nevada State Journal (Reno), March 29, 1935; Charleston (West Virginia) Daily Mail, June 5, 1938; and the Lowell (Massachusetts) Sun, August 3, 1942, among others. Dolph Camilli originated the Goo-Goo nickname when they were Cubs rookie teammates, according to the Brooklyn Eagle, July 12, 1942. Newspaper accounts and sports columns also frequently referred to Galan as “Little Augie Galan” over the years; though he was of slight frame, Galan was listed as just a half-inch short of 6 feet in height.

6 Peter Golenbock, Wrigleyville: A Magical History Tour of the Chicago Cubs (New York: St. Martin’s, 1999), 253. Actually, Cavarretta’s memory had slightly faded. According to Baseball-Reference.com, Galan played in left field exclusively in 1935, as fellow Californian Frank Demaree patrolled center. Galan did play center field in 1936, but then went back to primarily playing in left.

7 Hammond (Indiana) Times, October 24, 1935.

8 Berkeley (California) Daily Gazette, February 20, 1936.

9 Golenbock, 253; Donald Honig, Baseball When the Grass Was Real (New York: Coward, McCann and Geoghegan, 1975), 146.

10 John Thorn et al., eds. Total Baseball (Kingston, New York: Total Sports, 1999 [Sixth Edition]), 288, 875; BaseballLibrary.com; bleedcubbiesblue.com.

11 Hutchinson (Texas) News, September 28, 1938.

12 Lowell Sun, July 6, 1939; Nevada State Journal, April 11, 1939; Barney, 42; Saratoga Springs (New York) Saratogian, July 1, 1941; Warren Brown, The Chicago Cubs (Carbondale, Illinois: Southern Illinois University, 2001 [originally published 1946]), 199-200; Dick Bartell recalled, “Herman, Jurges, and Galan were sort of a club within the club. They did everything together. Galan and Jurges were jokesters.” Dick Bartell with Norman L. Macht, Rowdy Richard (Berkeley, California: North Atlantic Books, 1987), 228.

13 Baseball Register (St. Louis: The Sporting News, 1943), 141. Lowell Sun, August 26, 1941; Barney, 42, Brooklyn Eagle, March 3, 1942.

14 Brooklyn Eagle, April 21, 1943, and July 3, 1944; Spalding, 99; Barney, 42.

15 Brooklyn Eagle, February 9, 1943; Cava, 95.

16 Brooklyn Eagle, December 10, 1946. Heusser, in fact, never appeared in a single game for the Dodgers.

17 Brooklyn Eagle, June 10, 1947, February 20, 1949; Bob McConnell and David Vincent, SABR Presents the Home Run Encyclopedia (New York: Macmillan, 1996), 540.

18 Dennis Snelling, The Pacific Coast League: A Statistical History, 1903-1957 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Co., 1995), 185; Oakland Tribune, December 29, 1953; Danny Peary, ed., We Played the Game: Memories of Baseball’s Greatest Era (New York: Black Dog and Leventhal, 1994), 264.

19 Big Spring (Texas) Daily Herald, March 27, 1945; Spalding, 99; New York Times, December 30, 1993.

Full Name

August John Galan

Born

May 23, 1912 at Berkeley, CA (USA)

Died

December 28, 1993 at Fairfield, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.