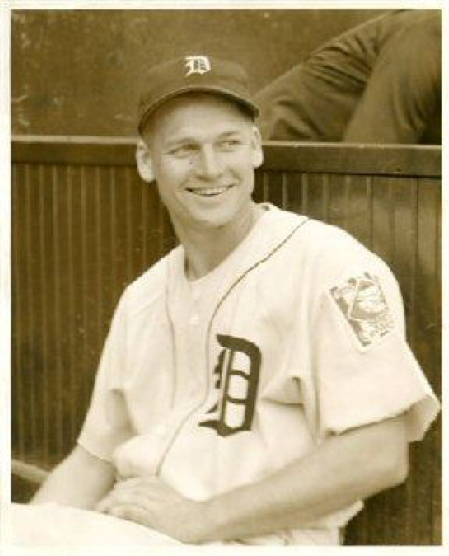

Benny McCoy

Benny McCoy was the talk of every town in 1940 when the obscure rookie became baseball’s first big-money free agent. He failed to live up to the hype — who could? — and crumpled under the weight of great expectations. “Benny’s problem was too much attention,” Philadelphia Inquirer columnist Cy Peterman wrote.1 We’ll never know whether he was any more than an ordinary player because World War II cut his career short.

Benny McCoy was the talk of every town in 1940 when the obscure rookie became baseball’s first big-money free agent. He failed to live up to the hype — who could? — and crumpled under the weight of great expectations. “Benny’s problem was too much attention,” Philadelphia Inquirer columnist Cy Peterman wrote.1 We’ll never know whether he was any more than an ordinary player because World War II cut his career short.

Benjamin Jenison McCoy was born in Jenison, Michigan, just outside Grand Rapids, on November 9, 1915. He was the ninth child and seventh son of Elmer Wiley McCoy, the superintendent of a dairy farm, and the former Winifred Pfeiffer. The family moved to the next-door town of Grandville, where Elmer worked as a railroad mechanic.

The blond baby of the family spent his childhood chasing after his older brothers, following them into sandlot ball. He always maintained that some of his elders were better players, but it was the youngest who got the attention when he played shortstop for the semipro Grandville Merchants. A local sportswriter touted him to Tigers scout Wish Egan. After McCoy hammered a homer, a triple, and a single in an exhibition game against the Tigers, Egan signed him in 1933. No bonus, just the promise of a contract. McCoy was 17, though he was listed as a year or more younger on team rosters throughout his career.

McCoy worked his way up through the Detroit farm system for six years. The stocky left-handed batter Egan called “the little bowlegged kid” was a consistent .300 hitter with doubles and triples power.2 But he was a man without a position, shuttled around the outfield and infield.

When he stuck with the top farm club at Double-A Toledo in 1938, manager Fred Haney put him at second base. Muscled up to around 170 pounds on a 5-foot-8 frame,3 he pounded 17 home runs to go with his league-leading 16 triples and a .309 batting average. Earle Mack, son of the Philadelphia Athletics owner, tried to buy his contract, but McCoy was earmarked for Detroit.

He got his first chance in a seven-game late-season trial. In his first start, he led off the game by striking out against the Indians’ 19-year-old wonder boy, Bob Feller. McCoy had plenty of company; Feller struck out 18 Tigers that day, then a major-league record.

McCoy went to spring training with the Tigers in 1939, but not even a two-homer game could earn him a spot on the roster. Back in Toledo, he was hitting .323 in July when Detroit’s perennial All-Star second baseman Charlie Gehringer went down with a severe charley horse. The 23-year-old McCoy stepped in with big spikes. In his first game he delivered two doubles and a single. His 30 appearances as Gehringer’s replacement included a six-RBI game and another with five, and a batting line of .325/.426/.517.

His neighbors from Grandville came to Briggs Stadium to honor their hometown boy on August 9. With his mother, two brothers, and a sister looking on, McCoy received a shotgun and hunting knife from the mayor. Benny made their trip worthwhile when he rapped out two hits and scored twice as the Tigers routed the White Sox, 10-3.

After Gehringer recovered and reclaimed his job, McCoy got a September tryout at shortstop. He capped his breakout season by slamming a double in the final game, driving pitcher Bobo Newsom home with the winning run in his 20th victory. McCoy hit .302 with an .842 OPS in 55 games. But in a season wrecked by injuries, the Tigers sagged to fifth place. “If we had McCoy two weeks earlier than we did when Gehringer was hurt, we would have finished higher than we did,” manager Del Baker said.4

Another Wish Egan discovery, center fielder Barney McCosky, batted .311 and scored 120 runs in his rookie season. “In Barney McCosky and McCoy the Tigers appear to have snagged two of the greatest young stars in the majors this year,” Leo McDonnell wrote in the Detroit Times.5 Yet the club gave up one of those budding stars in December, trading McCoy with pitcher George Coffman to the Athletics for right fielder Wally Moses.

Manager Baker revealed that he had only reluctantly parted with the hard-hitting, versatile rookie. “Mr. Mack,” Baker told the A’s owner and manager, “we’ve given you a high-class big league ball player.”6 But Tigers general manager Jack Zeller thought McCoy had been playing over his head and, besides, had “bad hands.”7 Moses was an established .300 hitter with a five-year track record, while McCoy’s resume was still more potential than performance.

A snag developed within 48 hours. Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis withheld approval of the trade pending his investigation of alleged underhanded dealings in the Detroit farm system. When a sportswriter called to ask about the investigation, Landis barked, “When there is anything to report it will be promptly passed on to you. Goodbye!”8 McCoy, who was at home driving a truck for a beer distributor, passed an uneasy Christmas not knowing where he would play. He, Coffman, and Moses sat in limbo for more than a month.

Judge Landis had been waging a futile crusade against the “evil” farm system that made minor-league clubs slaves of the majors and deprived players of “their essential rights.”9 Two years earlier he had declared 74 Cardinals minor leaguers free agents because of rule violations in the handling of their contracts. He had also freed a Cleveland farmhand, Tommy Henrich, who signed with the Yankees for a $20,000 bonus. At the 1939 winter meetings, National League owners had voted unanimously to limit the commissioner’s authority over farm systems, but the American League refused to go along, and Landis cast the deciding “no” vote.

Now Landis had the Tigers squarely in his sights, and he hit the club with a scattershot attack that wiped out more than half of its farm system. On January 14, 1940, the commissioner made 92 Detroit players free agents, including McCoy, Dizzy Trout, Roy Cullenbine, and Johnny Sain. He charged that the Tigers had used “fake agreements [and] cover-up” deals to hide players under their control. He ordered the team to pay $47,250 to 14 other players who had been victims of the chicanery.10 (The Tigers retained Trout by convincing Landis that the pitcher’s contract had been handled by the book.)

A bidding frenzy broke out with McCoy as the blue-ribbon prize. He was living with his parents; as soon as they had a phone installed, it started ringing. At least 10 teams made offers. “I’m tired of sitting on the bench and I’m tired of switching positions,” McCoy said. “I want to go with a club where I’m sure of getting a real chance of making good.”11

Connie Mack, having had him and lost him, was determined to get him back. He sent his son Earle to Grandville with a promise to top the highest bidder. He handed McCoy a $45,000 bonus, the biggest in history, plus a two-year contract at $10,000 a year, twice his previous salary. The bonus, worth around $837,000 in 2020 dollars, was more than the greatest stars were being paid. Earle said the publicity was worth the price.12

With the signed contract in hand, Earle hustled McCoy onto a train for Philadelphia. The next night Connie Mack stood before the annual sportswriters banquet at the Penn Athletic Club and pointed to the balcony, where a spotlight fixed on his new phenom. “Come down here, Benny McCoy,” he commanded.

“I hope you don’t think I’m a gold-digger,” McCoy told the crowd of 1,000. “I just did the best I could for myself. I know I’m not a star, and I know I’ll be on the spot next season. But I’m going to ignore all the publicity and just hustle as well as I know how, and I only hope I can play a big part in making Mr. Mack’s cherished dream of another championship team come true.”13

“Acquisition of McCoy completes what should be a grand young infield,” Mack commented, “and we certainly should be pennant contenders by 1941.”14 The 77-year-old saw a chance to return to glory after selling his stars during the Depression while his team fell from World Series champion to never-ran. His high hopes would be brought low by hard facts: He still had a lousy ball club.

Asked about his windfall, McCoy said he didn’t even buy a new car; his old one was running just fine. He did buy a house for his parents and another for a brother and sister who were in need.

The big payoff put him under a permanent spotlight. On the train from Philadelphia to spring training in Anaheim, California, the gilded one was as big an attraction as Connie Mack at every stop. “McCoy made speeches from the train like a presidential candidate,” the Inquirer’s Jimmy Isaminger wrote. “I have been going on training trips since the days when you could buy something for a dollar, but I never saw that before.”15

“Every time I picked up a glove or approached the plate, someone wanted a photograph or an interview or an autograph,” McCoy recalled. “The same thing when the season got underway and me out there realizing every eye was on me every second.” He pointed out that nobody raised an eyebrow when one club paid thousands of dollars to another club to buy a ballplayer, but everybody got excited when the money went to the player instead of a team owner.16

McCoy opened the season leading off and playing second base, but in the first six games he accumulated more errors (4) than hits (3). Philly fans were quick to judge and let him know what they thought. Opposing teams were taunting him, too. “I’m no star and I know it,” he protested. “I never claimed to be a great player, but I can play pretty good ball…. Was I supposed to have turned the money down? Mom would have spanked me if I did.”17

On a visit to Yankee Stadium, he heard how the boo birds cawed at Joe DiMaggio when he failed to deliver a hit every time up. Seeing that even the great DiMag was not immune, McCoy thought, “I’m the Joe DiMaggio of the Philadelphia A’s.”18

By midseason his batting average was stuck around .250 and Mack was losing patience. “McCoy hasn’t been hitting as I expected he would,” the old man said, “and his fielding hasn’t been up to our standard.”19 Isaminger commented that “he is weak on thrown balls and going back on pop flies.”20

McCoy finished with a league-leading 34 errors at second base and range factors well below average to go with a batting line of .257/.345/.373. Mack reportedly put him on waivers in the hope of arranging a trade, but found no takers. “The fact is that McCoy, focal point of the 1940 A’s, has been a failure,” columnist Cy Peterman observed, adding, “A fine boy who has tried hard, we certainly hope 1940 was not his best performance, for if so he simply is not major league.”21

“I have forgotten it,” McCoy said of his 1940 season as he arrived to begin work the next spring. “I hope everyone else will.”22 But he lost his starting job to Duke University product Crash Davis and opened the season on the bench. He was soon back in the lineup when Davis failed to hit. In his first start, McCoy went 4-for-5 and contributed to a game-winning ninth inning rally against the Yankees. That ignited him on a tear that kept his batting average around .300 until the end of May, when he faced a different challenge.

Although Pearl Harbor was still in the future, the United States had instituted a military draft to prepare for the looming threat of war. McCoy’s draft board in Grand Rapids classified him 1-A, available for induction in June. He was 25 and unmarried, but filed an appeal on the grounds that he was supporting his ailing father, his mother, a sister, and a brother.

When the board confirmed his 1-A classification, he flew home to plead in person for a deferment and was rejected again. The board ruled that he couldn’t claim hardship because he could use some of his fortune to support his family while he was in the service. McCoy appealed to the court of last resort, President Roosevelt, arguing that the board had no legal authority to require a man to use up his savings. In August he was granted a deferment by presidential order.23

While he was sweating out his draft status, McCoy endured an 0-for-22 stretch in June and his batting average dwindled to .241 by mid-July. Almost exactly at the time his deferment came through, he rallied to finish at .271/.384/.368 with 8 homers and 95 bases on balls. But his 27 errors were second in the league, and Mack registered his disgust with infielders McCoy, shortstop Pete Suder, and third baseman Al Brancato. “I never realized how bad they were until Wednesday in Washington,” Mack said in September. “They made six errors — when they hurt worst — and should have been charged with three more. If we are going to get anywhere next year I will have to make changes.”24

The Grand Rapids draft board forced Mack to make changes during the winter by revoking McCoy’s deferment. Expecting an immediate call-up, he enlisted in the Navy in February 1942. He took the oath at the Great Lakes Naval Training Station outside Chicago, where former Tigers manager Mickey Cochrane was assembling a big-league caliber baseball team. McCoy started at second base for Lieutenant Cochrane’s Service All-Stars in a July 7 benefit game against the American League stars, winners of the previous night’s major-league All-Star Game. McCoy went 0-for-2 as the paid crowd of 62,094 in Cleveland saw hometown hero Bob Feller of the Navy take a pounding. The American Leaguers won, 5-0, with part of the gate receipts going to the Army and Navy Relief Fund.

McCoy played ball for the Navy at Great Lakes, Norfolk, and San Diego until 1944, when he shipped out to spend more than a year and a half in Brisbane, Australia, and Subic Bay, Philippines. He and Dominic DiMaggio put together a team in the Philippines that included major leaguers Phil Rizzuto, Charlie Wagner, and Don Padgett, but they played only a few games. McCoy said service ball was not serious competition: “It was merely for relaxation — a chance to get out of drills — and don’t think anybody wanted to go to the hospital with a broken ankle or leg on those diamonds.”25

The Navy discharged McCoy just in time for spring training in 1946. He joined a mob scene at the Athletics camp as returning servicemen and wartime replacements jostled for jobs. McCoy was now 30, although the roster listed his age as 28, and he was one of the club’s highest paid players at $10,000. The press named him as the favorite to reclaim his starting position at second base, but the 83-year-old Mack disagreed. Mack said he had shown nothing at bat or in the field, and released him on March 29.26

With just about two weeks left before Opening Day, most teams were sifting through a similar glut of players. Detroit manager Steve O’Neill welcomed McCoy back for a tryout, but cut him after 10 days, saying the Tigers had no room for the onetime phenom. McCoy told sportswriters he had several minor-league offers and was considering the Mexican League, which was tempting major leaguers with big-money contracts.

Instead, he joined the St. Joseph Autos of the semipro Michigan-Indiana League, one of many new circuits that sprang up after the war. Some semipro teams paid salaries comparable to those in the high minors. The Autos, sponsored by the Auto Specialties Manufacturing Co. of St. Joseph, Michigan, had the advantage of being just 80 miles from McCoy’s home in Grandville. They were a powerhouse; one sportswriter commented, “The situation might be likened to having the [defending National League champion] Chicago Cubs join the M-I League.”27

The Autos already had a firm hold on first place when McCoy entered the lineup in June. They swept through the semipro National Baseball Congress tournament in Wichita, Kansas, winning seven straight games to claim the championship behind the pitching of former Tigers left-hander Roy Henshaw, then returned home to raise the M-I League pennant with a 50-15 record.

Longtime NBC president Ray Dumont later named the 1946 Autos as the strongest semipro outfit in tournament history. The club placed five players on the NBC All-America team, although McCoy was not one of them.

After the season the 31-year-old bachelor married Ruth Eleanor Austin. The first of their three daughters was born the next year.

Like McCoy, many other war veterans had been released by their teams after spring tryouts in 1946. But the law entitled returning servicemen to reclaim their prewar jobs for one year as long as they were still able to do the work. Baseball officials argued that the released players had lost their skills while in military service. When second baseman Al Niemiec appealed his release by the Pacific Coast League Seattle Rainiers, a federal judge ordered the club to pay him his full season’s salary whether it played him or not. The Sporting News estimated that more than 1,000 professional players could win back pay under the precedent set by Niemiec.28

In March 1947, McCoy and three others filed similar complaints with the support of Amvets, a veterans organization. Amvets national commander Ray Sawyer charged that baseball was guilty of “flagrant disregard” of the players’ legal rights. In a settlement negotiated by the U.S. attorney in Philadelphia, McCoy reportedly received from $7,500 to $10,000.29

He returned to the St. Joseph team in 1947. Rebranded the Auscos (an acronym for the sponsor) and again loaded with former professionals, they failed to repeat as national champions. They were eliminated in the early rounds of the NBC tournament despite McCoy’s 11-for-19 hitting splurge. He batted .325 for the season, and a local sportswriter commented, “Bright star of the team’s inner defense the past two years, McCoy has become a favorite of twin city diamond fans for his hustle, aggressiveness and fine team spirit.”30

McCoy took over as the Auscos’ manager in 1948, but resigned after another disappointing season. He continued to play semipro ball in the Grand Rapids area until his job as a car salesman began taking up too much time. “The new car business is so good that they’ve got me hopping all day long,” he said in 1950. “I’d have a pretty hard job finding time to practice.”31

Benny McCoy was one of the oldest living major leaguers when he died on his 96th birthday, November 9, 2011. He never publicly expressed any bitterness about his short big-league career. “That was probably the best era in baseball,” he told a reporter late in his life. “Ted Williams, Jimmie Foxx, Hank Greenberg, Joe DiMaggio, Joe Cronin. Those guys could play.” 32

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Joe DeSantis and checked for accuracy by SABR’s fact-checking team.

Notes

1 Cy Peterman, “Janitors, What’s the News? Those A’s and Phils Again?” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 2, 1940: 19.

2 Bob Murphy, “Bob Tales,” Detroit Times, January 24, 1940: 16.

3 Although Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet show 5-feet-9, a questionnaire McCoy filled out says 5-feet-8 (in his file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame library, Cooperstown, New York).

4 Charles P. Ward, “Ward to the Wise,” Detroit Free Press, October 3, 1939: 17.

5 Leo McDonnell, “Gehringer and York to Return This Week,” Detroit Times, August 13, 1939: 2-7.

6 Ward, “Baker Sorry to See McCoy Leave,” Detroit Free Press, December 10, 1939: Sports-1.

7 H.G. Salsinger, “Benny Now Has Chance to Show He’s the Real McCoy,” The Sporting News (hereafter TSN), January 25, 1940: 3.

8 Associated Press, “‘No Comment’ — Landis,” Philadelphia Inquirer, December 11, 1940: 24.

9 David Pietrusza, Judge and Jury (South Bend, Indiana: Diamond, 1998), 368.

10 Associated Press, “Tigers Suffer as Landis Cracks Down on Farm System,” Adrian (Michigan) Daily Telegram, January 15, 1940: 8

11 Murphy, “Sentiment Sways McCoy Towards Joining Mack,” Detroit Times, January 26, 1940: 21

12 Shirley Povich, “This Morning,” Washington Post, April 26, 1940, in HOF file.

13 Frank O’Gara, “Ben M’Coy on Spot, Promises to Hustle,” Philadelphia Inquirer, January 31, 1940: 25.

14 Associated Press, “McCoy Gets $65,000 for Signing Papers with Philadelphia,” Adrian Daily Telegram, January 30, 1940: 6.

15 James C. Isaminger, “Benny Is Always on Location, Never Fails to Look Pleasant,” Philadelphia Inquirer, February 29, 1940, in HOF file.

16 Peterman, “McCoy, Left to Himself, Shows He’s Big Leaguer,” Inquirer, May 22, 1941: 25.

17 Povich, “This Morning.”

18 Kostya Kennedy: 56: Joe DiMaggio and the Last Magic Number in Sports (New York: Sports Illustrated, 2011), 208.

19 Isaminger, “Johnson, Willard, Rubeling Sidelined,” Inquirer, August 13, 1940: 21.

20 Isaminger, “Yankees Defeat Athletics on Gordon’s Homer in 11th,” Inquirer, August 12, 1940: 19.

21 Peterman, “Janitors, What’s the News? Those A’s and Phils Again?” Inquirer, September 2, 1940: 19.

22 Stan Baumgartner, “Chubby Dean, Benny M’Coy on the Spot This Season,” Inquirer, February 27, 1941: 27.

23 “Mack Considering Pact With Orioles,” TSN, August 21, 1941: 3.

24 “Mack Disgusted with Infield,” Inquirer, September 5, 1941: 27.

25 J.G.T. Spink, “Looping the Loops,” TSN, February 7, 1946: 6.

26 Baumgartner, “Athletics Release 7,” Inquirer, March 30, 1946: 14.

27 “Snorter,” “Sports Hash,” Benton Harbor (Michigan) News-Palladium, June 25, 1946: 6.

28 Jeff Obermeyer, “Disposable Heroes: World War II Veteran Al Niemiec Takes on Organized Baseball,” Baseball Research Journal (SABR, Summer 2010), https://sabr.org/research/disposable-heroes-returning-world-war-ii-veteran-al-niemiec-takes-organized-baseball.

29 United Press, “Majors Accused of Violating Ex-Servicemen’s Rights,” Pittsburgh Press, March 27, 1947: 35; “Major Flashes,” TSN, April 9, 1947: 23.

30 “Auscos Baseball Team Disappointing Past Year,” St. Joseph Herald-Press, December 31, 1947: 2.

31 Jerry Kuhn, “Just Browsin’ Around,” St. Joseph Herald-Press, April 26, 1950: 10.

32 Becker, Bob, “An Original Free Agent,” Grand Rapids (Michigan) Press, July 14, 2007: C1.

Full Name

Benjamin Jenison McCoy

Born

November 9, 1915 at Jenison, MI (USA)

Died

November 9, 2011 at Grandville, MI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.