Bobby Bonner

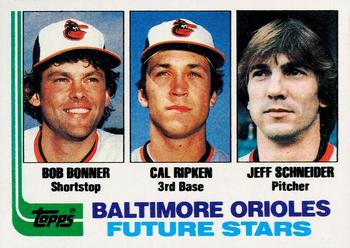

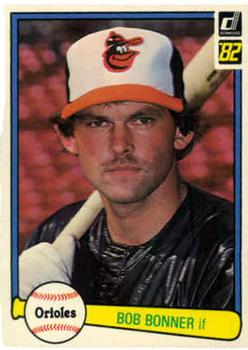

Four years before Bobby Bonner and Cal Ripken, Jr. appeared on their first Topps baseball card together — a 1982 Orioles Future Stars issue — they stood side by side at shortstop in Bluefield, West Virginia, after signing with the Baltimore organization on the same day. “I took ground balls with him and watched him play,” Ripken remembered thinking. “And I went, ‘God, this guy is great.’”1 Of course, Ripken seized the shortstop job as a rookie in ’82 and his stranglehold lasted more than 14 years. To discover his own destiny, Bonner had to leave baseball behind, make a leap of faith and travel more than 7,500 miles to become a Christian missionary in Zambia.

Four years before Bobby Bonner and Cal Ripken, Jr. appeared on their first Topps baseball card together — a 1982 Orioles Future Stars issue — they stood side by side at shortstop in Bluefield, West Virginia, after signing with the Baltimore organization on the same day. “I took ground balls with him and watched him play,” Ripken remembered thinking. “And I went, ‘God, this guy is great.’”1 Of course, Ripken seized the shortstop job as a rookie in ’82 and his stranglehold lasted more than 14 years. To discover his own destiny, Bonner had to leave baseball behind, make a leap of faith and travel more than 7,500 miles to become a Christian missionary in Zambia.

Robert Averill Bonner was born on August 12, 1956, in Uvalde, Texas, the fourth of Keros Johnson Bonner and the former Clara Juanita Ratliff’s five children. They lived on a ranch that produced saddle blankets and mohair cord in Leakey — pop. 587, about 100 miles west of San Antonio. There, Bonner rode horses, fished, swam, and explored caves on what had once been Comanche land.

When he was 11, the family moved 220 miles southeast to Corpus Christi. His father, who’d been aboard the U.S.S. Enterprise during World War II’s Battle of Midway, had sold the ranch and bought a trucking rig in an effort to make ends meet. The Bonners lived check-to-check and ate beans and cornbread every night

Bonner accompanied his dad on long annual rides to Montana and Colorado but spent much of his time playing sports. To emulate his older brothers, he’d started running track and playing basketball and football, though he mostly avoided baseball after taking a ball in the face at age 8 or 9. “I was afraid to play baseball,” he said. “My heart was more into football, even though that seems like a scarier sport.”2

In Corpus Christi, however, Bonner “literally played every league I could enter.”3 Little League, Pony League, Colt League, then on to King High School where he was a four-sport standout for the Mustangs. In baseball at King, he batted .451 as a junior, followed by .525 as a senior, earned first-team all-American honors, and played in the first Texas high school All-Star game at the Houston Astrodome.4 When he pitched in summer leagues, he averaged 17 strikeouts per game with a 90-mph fastball.5

Bonner was an intense player with an all-out style that took a toll on his body. After undergoing his first knee operation in ninth grade, he was up to four surgeries by his 1974 graduation. He overheard doctors warning his mother that he could be crippled for life within a few years if he kept playing baseball.

Nevertheless, the Montreal Expos drafted him in the 10th round and offered him $30,000 plus college costs to sign as a pitcher. “Management told me that I had been knocked all the way down the list from top pick because of injury concerns,” Bonner said.6 He turned down the offer and fielded more than 20 college scholarship offers to pitch, but he wanted to play every day in the infield. After coach Tom Chandler promised Bonner that he could do just that at Texas A & M, he agreed to join the Aggies. When the Kanas City Royals drafted him in the ninth round following his junior season in 1977, he almost turned pro, but Chandler convinced him that he could rewrite Texas A & M’s record book if he returned for his senior year. Bonner earned all-Southwest Conference honors twice for the Aggies and once went 69 straight at-bats without striking out. Though he departed with single-season school records for hits, doubles and triples; plus career-leading totals of runs, hits, doubles and total bases, his marks have since been surpassed.7 “Records are made to be broken,” he said in 2007.8

In 1978, Bonner was named the second-team All-America shortstop, behind only Arizona State’s Hubie Brooks.9 With the Boulder Collegians summer-league club the year before, Bonner had played shortstop while Brooks manned center field and 1978 National League rookie-of-the-year Bob Horner played second base.10

Two days after the Baltimore Orioles picked Bonner in the third round of the 1978 draft, scout Ray Crone signed him to his first professional contract.11 When second-round pick Cal Ripken, Jr. took grounders next to Bonner in Bluefield shortly afterwards, he was so impressed by the Texan’s fielding skills that he admitted thinking, “I’m never going to play here.”12

Ripken did play shortstop for Bluefield, however, while Bonner began his career with the Double-A Charlotte (NC) O’s in the Southern League. He injured his back in an early-season collision, missed six weeks, and played only 35 games, batting .234 with two doubles in his first taste of the pros.

His life changed dramatically that off-season. Bonner had married the former Rebecca Sue Petty during his first year at Texas A & M. Their first daughter Angela had been born in the summer of 1975, and number two, Krissy, was a couple months old. They would be joined by Stacy and Amanda in ensuing years. When Bonner arrived home after his first pro season, he was surprised to find his wife Becky reading her Bible, praying regularly, and consistently attending church.

“I was a hell-raiser,” Bonner confessed to a reporter 18 months later. “I drank every day, no less than six beers a day. I craved it. My marriage was on the rocks as a result. I was in the drug scene too. I smoked pot. I’ve done LSD, coke. I’ve done everything but put the needle in my arm.”13

That all changed in October 1978 when, in Bonner’s words, “I realized I was a sinner. I trusted Jesus Christ as my personal savior, and He forgave me and changed my life.”14 He discussed his transformation with his brother, K.K., who told him that he’d had a similar experience and even considered going to Africa as a missionary.

Bonner fielded a different reaction to his new lifestyle in spring training. “I walk in with a Bible underneath my arm and it freaked everybody out. ‘Who is this guy?’ you know.” he recalled. “There was guys I was running with in ’78 that now I’m praying for and asking them to come to church. They just said, ‘Man, who is this guy?’”15

Back at Charlotte in 1979, he enjoyed a terrific season. But when Orioles farm director Tom Giordano learned that he was leading Bible studies at the ballpark, he ordered him to stop, threatening fines if necessary. Reluctantly, the shortstop moved them to his home or hotel room. “Do you know what was so hypocritical about that whole thing?” asked Bonner. “Every time the Orioles had a prospect that they had spent a lot of money on that was having problems with drugs or alcohol, guess who they called? They called me to talk to him, but not at the ballpark.”16

He was a Southern League All-Star in ‘79, only missing leading the circuit’s shortstops in fielding because a month’s worth of games at second base and a brief Triple-A call-up left him 14 games short of qualifying. Bonner’s .291 batting average, 29 doubles, 7 homers and 67 RBIs would be the best numbers he’d ever produce as a pro. After a brief stop in the Florida Instructional League after the season, he went to Venezuela and hit .305 in 71 games for the Tigres de Aragua.17 When the Reds’ star shortstop Dave Concepcion joined that club, Bonner shifted positions and earned recognition as the league’s all-star third baseman.18

Bonner moved up to Triple-A Rochester in 1980 and spoke candidly about his former lifestyle in an early-season interview. “If Baltimore knew what I had done, they never would have drafted me,” he said.19 When the Orioles visited for a July 24 exhibition, he went 3-for-3 with a double and a triple but managed only a .241 batting average with a dozen extra-base hits in 133 regular-season games.20

Nevertheless, he led league shortstops in most fielding categories after recovering from an early season hyperextended elbow and the league’s managers and media voted him an all-star and the International League’s top rookie. His teammates voted him the Red Wings’ MVP. “The MVP award should go to the player who wins or saves the most games for his team,” Rochester GM Bob Drew observed. “I haven’t seen a guy do more for his team this season than Bonner has for us.”21

“He plays like Rick Burleson,” remarked Pawtucket manager Joe Morgan, comparing Bonner to the Red Sox star.22

Bonner even found a new place to worship in 1980. At the persistent urging of a teenage Red Wings fan, he visited Rochester’s First Bible Baptist Church for the first time. Soon, FBBC’s youth pastor, Mike Metzger, launched a ministry geared toward ballplayers based on an idea that came up at a weeknight Bible talk that Bonner attended. The program lasted for decades and impacted hundreds of players.23

Midway through the 1980 season, Bonner’s father-in-law died suddenly, and his minor league salary wasn’t enough to fly his wife and daughters to the funeral. After borrowing the money from the Red Wings, he gave up his apartment and moved in with the team’s trainer to cut his expenses. One night, after a tough loss, some members of his congregation showed up at Silver Stadium to hand him $400 they’d collected for him. “They don’t really have money,” he told The Sporting News. “They’re hardworking people. But it shows you the Lord provides.”24

A big league paycheck would help, of course, and baseball writer Peter Gammons reported, “More and more, I hear people touting Bob Bonner of Rochester as the Orioles next shortstop.”25 After the Red Wings were eliminated by Toledo in the International League playoffs in September, manager Doc Edwards told Bonner to meet the Orioles in Detroit. He’d been called up to the majors.

When Bonner arrived at Tiger Stadium, Orioles legend Brooks Robinson introduced himself and interviewed the Texan for a broadcast back to Baltimore. The shortstop’s first meeting with his manager, however, was much less cordial. “Who do you think you are?” Bonner remembered Earl Weaver asking.26 The skipper insisted that, despite front office pressure to play the rookie, he had no intention of doing anything but park him on his bench as the second-place Birds tried to catch the Yankees. “‘Sit, listen, and learn,’ that’s what he told me,” the shortstop recalled.27 Bonner debuted in Toronto on September 12 as a ninth-inning pinch runner for Lee May.

Two days later the Orioles were at Toronto on a cold, wet Sunday when Weaver hollered for “Bonnicker” to get in the game. Bonner, sitting next to fellow September call-up Mike Boddicker in the dugout, doubted the manager wanted him with the score tied in the ninth inning. Shortstops Mark Belanger and Kiko Garcia had both already exited for pinch hitters, however, so it was his turn indeed.

In the 11th, Bonner made both his first major league plate appearance and fielding chance. After Baltimore grabbed a 3-2 lead on Eddie Murray’s third solo homer of the day, the rookie grounded out to end the top of the frame. In the Blue Jays’ half of the inning, there was one out and a runner at second base when Barry Bonnell came to the plate. Bonnell smashed a one-hop shot to Bonner’s right that went through into left field, allowing the tying run to score. Orioles’ coach Cal Ripken, Sr. described it as an “impossible chance,” but the official scorer charged the rookie with a very costly error. 28 When the Orioles lost two innings later to fall five games behind in the AL East race with 19 contests remaining, Weaver was apoplectic in the post-game clubhouse.

“He’s yelling at the top of his lungs because my locker is right by his office. He was yelling and screaming, ‘Who do they think this guy is sending him to me? I didn’t want to play him, and he can’t even catch the ball,’ ” Bonner recalled.29 “He said I was not fit to play in the show,” he added. “No one had ever made an attack as personal and hateful as this one.”30

“Bobby Bonner was a great shortstop. But after Earl blasted him that day, he just crumbled and was never the same,” observed Boddicker.31

The shortstop didn’t get into another game until the Orioles were eliminated on the final weekend. One day after the season ended, Bonner’s 37-year-old brother, K.K., died of a heart attack.

That winter, Bonner worked in a Texas oil field. In spring training, a headline in The Sporting News read, “Belanger, 37, Has to Fight for Job,” referring to the eight-time Gold Glove shortstop entering his 17th and final season with the Orioles.32 Bonner was expected to receive a long look in Grapefruit League play, but he contracted viral hepatitis in February, spent four days in the hospital, lost 20 pounds and reported late to camp.33 Baltimore traded away number-two shortstop Kiko Garcia shortly before Opening Day, but kept Lenn Sakata and Wayne Krenchicki as reserve infielders while Bonner returned to Triple-A.

He got off to a slow start for Rochester but hit a grand slam in a seven-RBI outburst versus Charleston on April 27,34 and played all 33 innings of the epic marathon in Pawtucket that began on April 18 and finished on June 23. In between, he went back to the majors in mid-May when Sakata sprained an ankle, but only after Weaver and his coaching staff had voted unanimously that they preferred the powerful bat of Red Wings’ third baseman Cal Ripken, Jr.35 After consulting with his player development team, Orioles GM Hank Peters decided to promote Bonner rather than rush the future Hall of Famer. “We didn’t think all our people in the organization could be wrong,” Peters explained.36

“I’m no Bonner with the glove, but I don’t think he’s going to outhit me,” remarked Ripken, who temporarily became the Red Wings’ shortstop.37

Bonner joined the big-leaguers in Toronto and started the last five games of the road trip — all Orioles wins. On May 14, he legged out an infield hit against the Blue Jays’ Jim Clancy for his first major league hit, followed by a double in his next at-bat. The following night in Minnesota, he went 4-for-5 and stole his first base. Overall, he batted .296 in 10 games over two weeks.

When the Orioles sent him back to Triple-A, Bonner drove non-stop to Rochester to be on time for a May 28 doubleheader, but was knocked out of action leading off the opener when a pitch from Tidewater’s Jesse Orosco drilled him behind the knee.38 Later, a pulled hamstring caused him to miss five out of six midsummer weeks but, at year-end, the circuit’s skippers still named him one of the International League’s top 10 prospects.39 “Bonner was the heir apparent to Belanger,” observed Ripken, who also made the list. “He was one of the best shortstops I’d ever seen. He had a good year, and I thought it was his position for sure.”40

Bonner batted .404 in spring training 1982 and made Baltimore’s Opening Day roster, though Sakata started the bulk of the games at shortstop, including the first one. 41 On May 15, the slow-starting Orioles dropped to last place after a Bonner error led to a decisive unearned run in the bottom of the ninth. Weaver had just put him in the game, and the miscue came on what looked like an inning-ending double play. “When I charged for the ball, it hit the seam of the Astroturf and bounced off my face,” the Texan recalled.42 “After the game Earl calls me into his office in Seattle and cusses me out in front of around a dozen reporters. He called me every name in the book.”43

“Bonner was one of those reborn Christian kids and wore it on his sleeve, and Earl didn’t take to him. He never did. He crumbled him,” observed Hank Peters. “And this was one of the best-looking shortstop prospects you’ll ever want to see. Earl just destroyed that kid. He never did bounce back from it, which is a shame.”44

Bonner started in a Baltimore victory the next day but went 6-for-46 in limited opportunities over the next six weeks to drop his batting average from a poor .226 to an unacceptable .169. In July, Weaver moved Ripken to shortstop, where he started every Baltimore game for the next 14-plus years. Bonner went back to Rochester to become a second baseman and attempt to learn to switch-hit. Though he connected for a three-run homer in his first game batting left-handed, he abandoned the experiment after less than two dozen contests. At second base at least, he finished the year on a streak of 46 straight errorless games.45

After the season, Bonner spent the winter in the Baltimore area, working to convert himself into a useful utility player with Weaver retired and the Orioles under a new manager for 1983. According to Bonner, the new skipper, Joe Altobelli, warned him, “You need to learn to leave Jesus in the church and not bring Him to the ballpark.” When Bonner replied that Christ went everywhere with him, Altobelli answered, “Well, he ain’t going to Baltimore.”46

Bonner went to Rochester and appeared in only 61 games after breaking his hand trying to protect himself from an up-and-in pitch. As the Orioles closed in on a division title in September, he got into six games, but logged only two pinch-running appearances and five innings as a second baseman. Though he’d been measured for a World Series ring, he never received one and he was voted only a $500 portion of a 1983 champions’ $65,487.70 full playoff share.47

When Bonner found out he’d also been dropped from the club’s 40-man roster, he wanted out. But Peters told him that he couldn’t trade him and wouldn’t release him. Being outrighted to Triple-A meant Bonner would essentially be frozen there for 1984 since the Orioles couldn’t recall him without exposing him to waivers. Peters told a reporter, “What he needs is to go out and play a whole year and maybe impress people enough to get one final shot.”48

Upset, Bonner prayed and promised God that he would leave baseball at the end of the year. When he announced his upcoming retirement early in the season at Rochester, he was warned that it was career suicide. The Red Wings had so many injuries, however, that he appeared in 111 games, played seven positions and batted .277. He even pitched three times and was voted team MVP. The day after the season ended, he began teaching high school at Rochester’s North Star Christian Academy.49

Bonner brushed off offers from five big league teams but received an intriguing proposal from the Red Wings for 1985. He could come to the park after school let out, skip road trips until summertime and still earn triple his teaching salary. But he declined. “I love Jesus Christ more than baseball,” he explained. “I made a promise to him that I would not play again.”50

When a visiting speaker at Bonner’s church mentioned the need for missionaries in Africa, something awakened inside him. His late brother K.K. had considered it before, and Bonner felt called to pursue it. Despite advice to remain in Rochester to help build a sports ministry, and concerned friends questioning his sanity for subjecting his wife and daughters to the unknown, Bonner and his family moved to Zambia in 1989. “Africa will either get in your blood, or you will run from it as fast as you can,” he said.51

The country in Southwestern-Central Africa was plagued by high HIV infection rates, short life expectancy and epidemic infant mortality. Once Bonner arrived, he learned to navigate treacherous narrow roads, a bevy of wild animals and the unavoidable misunderstandings awaiting a Texan in a faraway country with 72 distinct tribes. “It was never the job of the nationals to understand me,” he said. “It was my job to understand them. I had moved into their village and into their culture.”52

Bonner made Zambia his home for more than two decades, pastoring, evangelizing, and training hundreds of locals to do the same on behalf of the Gospel. Former major league pitchers Frank Tanana and Mark Thurmond helped support his ministry. “Bonner is no longer an American, but a Zambian,” he remembers being told when the family of a deceased pastor he’d trained asked him to help wash and purify the body for burial. “The locals told me that they had never seen a white man help prepare a body in their history,” he said.53

His Zambian experience included one serious motorbike accident, four heart attacks and 19 bouts of malaria, including two of the dangerous cerebral type. It was in South Africa that a nearly fatal fight with black water fever ended his career as a field missionary in 2012.

He settled in Blue Springs, Missouri, where he’s the associate pastor of First Bible Baptist Church. Bonner is also the president of International Africa Missions; a group that trains local pastors and distributes Bibles throughout sub-Saharan Africa. As of 2020, IAM has planted 320 churches in seven countries, and operates a health clinic and orphanage for the deaf in Zambia. They’ve also opened five Bible institutes and spread their good news to over a half-million people.54

In 2000, Rochester inducted Bonner into the Red Wings Hall of Fame, and he was enshrined in the Texas A & M Athletic Hall of Fame the following year.

Six or seven years before Earl Weaver died in 2013, Bonner met him one last time after Ripken convinced his fellow shortstop to attend a charity fundraiser. When the Texan approached to shake his former manager’s hand, the “Earl of Baltimore” seemed surprised, saying Jim Palmer often reminded him that he’d ruined Bonner’s career. “I told him about Africa, and I said, ‘What people thought was bad, God meant for good,’” Bonner said, explaining that he held no grudge. “More than anything else, skip, ‘God loves you and so do I,’” he told Weaver. “He started crying. That meant everything to me.”55

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Bobby Bonner for the update on his life since his 2011 Book From the Diamond to the Bush in a telephone interview with the author on September 29, 2020.

This biography was reviewed by Gregory H. Wolf and Norman Macht and fact-checked by Bill Lamb.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Note, the author also consulted, https://internationalafricanmissions.org/about.html, www.ancestry.com, www.baseball-reference.com and www.retrosheet.org

Notes

1 John Eisenberg, From 33rd Street to Camden Yards, (New York: Contemporary Books, 2001): 316.

2 Bobby Bonner, From the Diamond to the Bush, (Fort Pierce, Florida: FBC Publications, 2011): 21.

3 Bonner, From the Diamond to the Bush: 31.

4 1981 Baltimore Orioles Media Guide: 87.

5 Bonner, From the Diamond to the Bush: 35.

6 Bonner, From the Diamond to the Bush: 32.

7 1981 Baltimore Orioles Media Guide: 87.

8 “Interview With Bobby Bonner,” December 19, 2007, https://www.ripkenintheminors.com/intbobbybonner.htm (last accessed September 28, 2020).

9 “The Class of the College Crop,” The Sporting News, July 8, 1978: 42.

10 Bonner, From the Diamond to the Bush: 37.

11 1981 Baltimore Orioles Media Guide: 87.

12 Eisenberg, From 33rd Street to Camden Yards: 316.

13 Greg Boeck, “Bonner Up from Depths to New Heights with Wings,” Democrat and Chronicle (Rochester, New York), April 9, 1980: D1.

14 Interview with Bobby Bonner.

15 Interview with Bobby Bonner.

16 Interview with Bobby Bonner.

17 Venezuelan League statistics from Pelota Binaria, http://www.pelotabinaria.com.ve/beisbol/mostrar.php?ID=bonnbob001 (last accessed September 28, 2020).

18 1981 Baltimore Orioles Media Guide: 87.

19 Boeck, “Bonner Up from Depths to New Heights with Wings.”

20 1981 Baltimore Orioles Media Guide: 86.

21 “Drew Supports Bonner,” The Sporting News, September 6, 1980: 58.

22 Peter Gammons, “One Thing About Steinbrenner: He Acts,” The Sporting News, August 30, 1980: 7.

23 Bonner, From the Diamond to the Bush: 59.

24 “Fans, Friends Support Bonner,” The Sporting News, September 13, 1980: 51.

25 Gammons, “One Thing About Steinbrenner: He Acts.”

26 Interview with Bobby Bonner.

27 Interview with Bobby Bonner.

28 Interview with Bobby Bonner.

29 Interview with Bobby Bonner.

30 Bonner, From the Diamond to the Bush: 66.

31 Eisenberg, From 33rd Street to Camden Yards: 356.

32 Ken Nigro, “Belanger, 37, Has to Fight for Job,” The Sporting News, March 21, 1981: 44.

33 Bonner, From the Diamond to the Bush: 70.

34 “Ripken Robs Homers,” The Sporting News, May 16, 1981: 40.

35 “Recall of Bonner Ruffles Feathers,” The Sporting News, May 30, 1981: 23.

36 Ken Nigro, “Bird Seed,” The Sporting News, June 6, 1981: 25.

37 “Corey Concerned Over Circuit Clouts,” The Sporting News, June 6, 1981: 41.

38 “Ripken Rips Pair of Three-Run Homers,” The Sporting News, June 27, 1981: 40.

39 1982 Baltimore Orioles Media Guide: 80.

40 Eisenberg, From 33rd Street to Camden Yards: 354.

41 1983 Baltimore Orioles Media Guide: 87.

42 Bonner, From the Diamond to the Bush: 77.

43 Interview with Bobby Bonner.

44 Eisenberg, From 33rd Street to Camden Yards: 356.

45 1983 Baltimore Orioles Media Guide: 87.

46 Bonner, From the Diamond to the Bush: 79.

47 “World Series Shares,” The Sporting News, November 21, 1983: 51.

48 Jim Henneman, “Orioles Drop Bonner From Roster,” The Sporting News, January 16, 1984: 44.

49 Bonner, From the Diamond to the Bush: 79.

50 Bonner, From the Diamond to the Bush: 97.

51 Bonner, From the Diamond to the Bush: 115.

52 Bonner, From the Diamond to the Bush: 131.

53 Bonner, From the Diamond to the Bush: 132.

54 Bobby Bonner, telephone interview with author, September 29, 2020.

55 Interview with Bobby Bonner.

Full Name

Robert Averill Bonner

Born

August 12, 1956 at Uvalde, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.