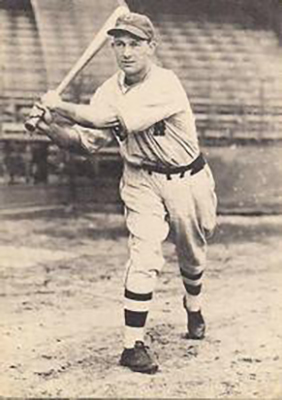

Buzz Boyle

The fourth member of the Boyle family of Cincinnati to play in the majors, Ralph “Buzz” Boyle, made a splash when he joined in the Brooklyn Dodgers at age 25 in June 1933 after brief appearances with Boston Braves in 1929 and 1930. Joining the Dodgers in midseason after some time in the minors, the speedy outfielder hit .299 in his rookie year. The Sporting News and other publications selected him for their 1933 National League All-Rookie Teams.1

The fourth member of the Boyle family of Cincinnati to play in the majors, Ralph “Buzz” Boyle, made a splash when he joined in the Brooklyn Dodgers at age 25 in June 1933 after brief appearances with Boston Braves in 1929 and 1930. Joining the Dodgers in midseason after some time in the minors, the speedy outfielder hit .299 in his rookie year. The Sporting News and other publications selected him for their 1933 National League All-Rookie Teams.1

The following year Boyle had a season to remember. He batted .305, tying the Dodger team record with a 25-game hitting streak. In the field, he led the majors in outfield assists and NL right fielders in range factor. Overall, he ranked eighth in WAR among NL position players. The performance earned Boyle MVP votes and a mention by Roger Kahn in The Boys of Summer as a Dodger he followed closely in his youth.2

Boyle’s career went in a different direction in 1935. He finished tied for second in the NL in outfield assists, but his batting average fell to .272, slightly below the league average. Following the season, the Dodgers traded Boyle to the Yankees, who assigned him to their Newark farm team. The contact-hitting speedster failed to return to the majors with the Bronx Bombers, despite regularly batting over .300 in the Yankee farm system.

Boyle then made his career in professional baseball off the playing field. He managed farm teams for the Yankees in Akron and Norfolk, and then the Muskegon (Michigan) Lassies in the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League in 1946.3

The Cincinnati Reds brought him back to major-league baseball in 1947 as the manager for their Providence affiliate. The next year Boyle became a member of the Reds permanent scouting staff, eventually becoming the organization’s head scout in the build-up to the Big Red Machine in the 1960s.4 Boyle left the Reds in 1968 following a change in ownership and worked as a scout for the Montreal Expos and Kansas City Royals.

***

The youngest of four children born to James and Emma (Hook) Boyle, Ralph Francis Boyle joined siblings Helen, Edward, and future major-leaguer Jim Boyle on February 9, 1908. His father, a captain in the Cincinnati fire department, encouraged his sons to emulate their uncles Jack Boyle and Eddie Boyle and consider a career in professional baseball.5 Ralph enthusiastically followed the advice.

Brother Jim gave Ralph his nickname – originally “Buzzy” – when the two boys were quite young. Neither could remember precisely why the name stuck in the family,6 but older siblings attributed it to Ralph’s constant talking. Eventually shortened to Buzz, it became commonly used professionally once Boyle joined the Dodgers, where his speed on the basepaths and in the outfield reinforced it.7

Benefiting from the baseball experience of his uncles and older brother, Ralph quickly established himself as a sports star at Elder High School in Cincinnati, where he lettered in three sports and captained the football team.8 His play for the New Era amateur team in 1927 caught the eye of scouts from the Boston Braves in the summer before his senior year.9

After graduating in 1928, he followed his brother Jim to Xavier University in Cincinnati. He played on the freshman football team10 and the Xavier reserve basketball team.11 But Boyle’s father had recently retired from the Cincinnati fire department and money was tight for the family. Ralph realized that he needed to provide some funds for his parents.12 The Boston Braves were waiting and Boyle signed on with their Providence Grays farm team in spring 1929.13

Boyle made it to the big leagues with the Braves in September that year after hitting .309 in Providence.14 When he entered his first major-league game on September 11, the Boyles became one of the few baseball families to have sets of brothers in successive generations play in the majors.15 Boyle went hitless in four at-bats with one strikeout in his debut. He played 17 games for the Braves that year, hitting his first major-league home run on September 29 in the Braves 3-2 loss to the Dodgers. He finished with a .263 batting average and an OBP of .333. The league, however, hit .294 that year and Boyle ended with a below-average OPS+ of 81 for the last-place Braves, who as a team had an OPS+ of 79.

Boyle spent most of the following year with Providence. The Braves called him up in September 1930, and Boyle made a single appearance as a late-inning substitute on September 27 in a game against Brooklyn, striking out in his only at-bat.

The Baltimore Orioles of the Class AA International League acquired Boyle from the Braves after the season. The press in Baltimore quickly acknowledged Boyle as an “important cog in the Oriole machine for his hitting, fielding, speed and arm in the outfield.”16 At age 23, Boyle played 157 games for Baltimore in 1931, hitting .312 with 10 home runs, 13 triples, and 36 doubles. As the season wound down, the Washington Senators purchased Boyle from the Orioles along with Johnny Gill.17

Washington manager Walter Johnson noted that, while Boyle might need more seasoning, he had the makings of a star.18 Johnson promised that Boyle would be given plenty of opportunity to show his stuff.19 The same article noted that the lefty hitter and thrower (5-feet-11, 170 pounds) had some trouble handling southpaws. That influenced his chances of sticking with the big club for the 1932 season.

Indeed, Boyle did not stick with the Senators, who returned him to the Orioles on March 28. Baltimore immediately installed him in the leadoff spot.20 He finished the season with a .314 average, including 36 doubles, 11 triples, and nine home runs. On June 6, he married Mary Grace Mannix, a Cincinnati girl, in Baltimore; eight hours later, he appeared with the Orioles in his normal leadoff spot to an ovation.21 Ralph and Mary Grace stayed married through Boyle’s death in 1978. They had two children, Terry and Dan.

While noted for his speed, Boyle never developed into a base-stealer. The O’s wanted to see more of it.22 Boyle admitted he could do better in that area, but he never acquired the knack for getting a jump on pitchers. Just how fast was he? The individual recognized as the second fastest member on the Orioles to Boyle ran the 100-yard dash in 10.4 seconds,23 so Boyle sprinted at least a bit faster than that.

Baltimore retained its leadoff hitter for the beginning of the 1933 season. Boyle again crushed the ball, hitting .364 through the first 51 games of the season. The Dodgers noticed and sent Del Bissonette and $7,500 cash to the Orioles for Boyle on June 7, 1933.24

The Brooklyn press and Dodgers manager Max Carey expressed some concern that Boyle’s success at Baltimore might not translate into success at the major-league level, in part owing to the difference between the balls used in the International League and those in play in the National League.25 The NL began experimenting with reducing the responsiveness of its ball following the 1930 season, when Hack Wilson hit 56 home runs and drove in 191 runs.

The experimentation reached its pinnacle (or nadir) with the ball used in 1933. NL home run totals, which had reached 892 in 1930, fell to 460 in 1933. By this time, the NL and AL baseballs were so different that in the inaugural All-Star Game in 1933, half the game was played with the NL ball and half with the AL “jackrabbit pellet” (as the New York Times described it).

Boyle’s three-season sojourn with the Dodgers began with him in center field for the Dodgers on June 10, batting in the leadoff spot. He promptly lined a triple to the wall in Ebbets Field. Soon, however, a condition described as muscle rheumatism slowed him down, and his batting average dropped to .227 by mid-June. Yet it did not stay there long.

Just as Ralph and Grace’s first son, Terry, was born on July 3, Boyle started to cement his position as a starter for the Dodgers. He raised his batting average to over .300 by mid-July; it remained near there for most of the rest of the season. That month the Brooklyn Daily Eagle noted that there was “no displacing the Greyhound Boyle now, so well is Buzz going.”26 The previous day’s headline had proclaimed that “Boyle Looks Like the Find of the Season.”27

The accolades kept coming Boyle’s way. “Boyle Stars Afield and at Bat for the Flock” was the Brooklyn Times Union headline on August 27 as the “young Boyle collected five hits and covered his post like a blanket.”28 As the season wound down, the Times Union led its sports page with “Boyle, Dodger Outfielder, Late Season Sensation of the National League.”29 Even so, the press noted that Boyle hadn’t yet proven his ability to hit lefties.30

Boyle finished the season batting .299 with 13 doubles and four triples but no home runs. The Sporting News and other publications named him to their NL All-Rookie Teams.31 However, the triple Boyle hit in his first at-bat for the Dodger in June was described as the longest hit he had all season.32 His lack of power was viewed as a limiting factor for him.33

In January 1934 the NL and AL agreed on a common baseball, which the New York Times described “as sort of medium between the jackrabbit of the American League at its fastest and the reaction ball of the National League at its slowest.”34 Boyle noted the improved performance of the new ball, and opined that he’d get some home runs with the additional 20 feet of carry he saw.35

As noted above, Boyle turned in quite a performance both offensively and defensively under new manager Casey Stengel in 1934. In addition to playing his typically outstanding defense and leading the majors with 20 outfield assists, he hit .305 and finished the year with 26 doubles, 10 triples – and, living up to his hope, seven home runs. His OBP was .376, well above the league’s .317.

Several noteworthy accomplishments occurred during the year. After starting the season on the bench despite hitting .486 in spring training,36 he went on a hitting tear beginning May 1. By going 4-for-5 in the first game of a doubleheader against the Phillies on June 5, he raised his batting average to .328. With that game, Boyle tied the Dodgers’ existing hitting streak record of 25 games. In the nightcap the Phillies again threw a right-hander, but Boyle did not start in the game. Instead, Stengel sent him in as a defensive replacement for the righty-hitting, slow-footed Hack Wilson in the bottom of the seventh with the Dodgers up 4-0. Unfortunately for Boyle, he came to bat in the ninth and struck out as the Bums lost to the Phillies, 5-4.37 Boyle’s streak is still tied for the fifth-longest in the history of the franchise. For the rest of his life, he held a grudge against Stengel for subbing him in late in the game with only one opportunity at the plate to extend his streak.38

A paired incident involved a doubleheader against the Cardinals on September 21. In the opener, Boyle broke up Dizzy Dean’s bid for a no-hitter in the eighth inning; then in the nightcap, he nearly spoiled rookie brother Paul Dean’s no-hitter on a bang-bang play at first for the final out of that game.39 Dizzy caught up with Boyle after the first game and told Boyle that his hit cost the St. Louis ace $5,000, because that’s what he would have insisted on being paid to pitch the next time he went out.40 After the second game, Dizzy caught up with Boyle again, placed his arm around the outfielder and said, “Boyle, I like you. But you know what would have happened if you beat that last one out.” Boyle admitted later, “Now that I think about it, I am glad I was out.”41

In 1935, Boyle continued to play defense in his customary style42 (he finished tied for second in the NL with 18 outfield assists). However, his plate production fell off. He finished the year hitting .272 with 17 doubles, nine triples, and four home runs in 127 games. The league batting average was .277 and Boyle’s OBP of .332 just barely exceeded the league’s mark.

In midyear, Boyle’s wife Mary Grace was dealing with a difficult pregnancy and was described as being “at death’s door” by the Brooklyn Daily Eagle.43 Boyle left the team to be with his wife in Cincinnati. A successful caesarian section, not the routine procedure it is today, saved both Mary Grace and the Boyles’ second son and last child, Danny.

Boyle signed a contract for 1936 with the Dodgers.44 It was expected that he’d have a battle to retain his starting position with the team,45 but he never got to show his stuff for Brooklyn again. On February 20, the Dodgers traded Boyle along with Johnny McCarthy and $40,000 to the New York Yankees for first baseman/outfielder Buddy Hassett.46 Boyle went straight to the Yankees farm team in Newark.

Boyle hit over .300 in three of his four full seasons in the Yankee farm system, one in Newark and three with the Kansas City Blues, but he never got back to the majors. At age 31, he served as a veteran influence for future Yankee stars Tiny Bonham and Phil Rizzuto , as well as Vince DiMaggio, on the stellar KC team of 1939, which won 107 games against 47 losses. Boyle moved on from the Blues after the 1940 season to manage (and play a bit) with the Yankees’ farm teams in Akron in 1941 and Norfolk in 1942.

In 1943, Boyle joined the war industries with Cincinnati Clock and Instrument.47 There he organized, managed, and played for a semipro team under company sponsorship.48 The team played against other similar squads in the Midwest and Negro League clubs traveling in Ohio. Boyle delivered the game-winning hit in the bottom of the eighth inning against the Negro American League’s Memphis Red Sox in the Clocks’ first game of the season held at Crosley Field (the home of the Reds).49

Following the war, Boyle sought to return to professional baseball, but no offers were forthcoming. Then, Max Carey – Boyle’s manager at Brooklyn in 1933, who’d become president of the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League – presented Buzz with an offer to manage the Muskegon Lassies.50 Boyle accepted, but not without reservations.51 Given the conservative nature of major-league franchise ownership, Boyle thought that joining the AAGPBL might eliminate him from any serious consideration for a future position at the top level. His reservation proved unfounded: the Reds offered him the role of managing the team’s Providence affiliate for the 1947 season.52

Family members had a different reservation about Boyle managing the Muskegon Lassies. Specifically, his coaching style included the liberal use of the type of colorful language that was quite inappropriate for an all-women’s team. His selection to manage the Lassies raised eyebrows for the same reason in the baseball press in Akron, where he had managed in 1941.53 This concern also proved unfounded. Many years later Boyle’s grandson, Dan Boyle, met Erma Bergmann of the Lassies. Buzz had converted her from a position player to a very successful pitcher in the league. Bergmann assured the younger Boyle that Buzz was always the perfect gentleman as the team’s manager.54

Following his stint managing the Reds’ Providence team, Boyle joined the organization’s scouting staff.55 He was elevated to head scout for the Reds and held that position through the mid-1960s.56 Boyle had a significant hand in signing Pete Rose, Jimmy Wynn (lost to the Astros in the expansion draft), Claude Osteen (traded to the Dodgers), Gold Glover Johnny Edwards, Bernie Carbo, and Billy McCool.57

In 1954 Boyle took the opportunity to scout a University of Cincinnati scholarship basketball player also showing great promise, mixed with great wildness, on the mound for the Bearcats.58 Buzz watched the pitcher in a game against Xavier University, unaware (as was UC baseball coach Ed Jucker) that the young man had sprained his ankle the previous day. The young hurler went eight innings but turned in a subpar performance against the Musketeers, losing 5-2.59

The Reds decided to pursue a contract with the player, but his wildness, as observed by Boyle, created a dilemma for the ballclub.60 If they offered “bonus baby” signing money (then, any bonus above $4,000), they would be required to keep the ballplayer on their major-league roster for two years; if they assigned him to the minors he could be claimed by any of the other big-league teams. The Reds concluded that he needed some minor-league experience and chose not to make a bonus-baby offer.61 (The Yankees also offered $4,000 and a minor league assignment.62) The player, Sandy Koufax, ultimately signed with his hometown Brooklyn Dodgers for a bonus of $14,000. Koufax, never assigned to the minors by the Dodgers, worked six mediocre years on the Dodgers’ major-league roster before he put together a six-year stretch that earned him his spot in baseball’s pantheon.

Boyle resigned as a Reds scout in 1968; a new ownership group had purchased the franchise in late 1966.63 Shortly thereafter, he joined the Montreal Expos scouting department with a special focus on the International League for the expansion draft.64 Boyle left the Expos at age 65 and joined the Kansas City Royals as a part-time scout in the final act of his long career.

Boyle was elected to the Hamilton County (Ohio) Sports Hall of Fame in 1964.65 He passed away in 1978 at the age of 70 from cancer. Ralph Boyle is buried in St. Joseph’s New Cemetery in Cincinnati – the same final resting spot as the other three Boyle family members to play in the major leagues.

Author’s Note and Acknowledgments

The author is the great-nephew of Buzz Boyle. The author would also like to express his appreciation for the anecdotes and information provided by Dan and Tay Boyle, grandsons of the subject ballplayer, and the author’s cousin Tom Holtmann.

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Bill Lamb and fact-checked by Rod Nelson.

Sources

In addition to the sources included in the Notes, the author relied on Baseball-Reference.com, Baseball-Almanac.com, and Retrosheet.com.

Notes

1 Dick Farrington, “Stellar Group of Recruits Became Major Regulars in ’33,” The Sporting News, October 19, 1933”: 3; Bill McCullough, “All-Star Rookie Nine Abounds in Quality-Boyle and Jordan of Dodgers Named on National Leagues’ First Year Team,” Times Union (Brooklyn, New York), November 16, 1933: 11.

2 Roger Kahn, The Boys of Summer, Harper-Collins e-books (reissue edition February 22, 2011): 34.

3 “Buzz Boyle to Manage Muskegon Girls,” Lansing (Michigan) State Journal, April 15, 1946: 5.

4 “Stars Will Greet Old Coach for His 25th Year at Elder,” Cincinnati Enquirer, February 20, 1952: 17.

5 Jim Kreuz, “Jimmie Boyle Only had a cup of coffee in the bigs…but his son managed to find an autographed NY Giants ball,” Sports Collector’s Digest, December 9, 1994: 148; Charles Richards, “Big Leaguers Don’t ‘Play’ Ball,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, August 20, 1933: 55.

6 Richards, “Big Leaguers Don’t ‘Play” Ball.”

7 “Hutcheson, Jordan, Stripp Nursing Injuries to Legs,” Times Union, July 16, 1933: 95.

8 “Boyle is Elder ‘Man of the Year,’” Cincinnati Post, March 12, 1971: 33.

9 “Scouts to View Work,” Cincinnati Enquirer, August 27, 1927: 8.

10 “Xavier Selects Two Captains,” Cincinnati Post, December 7, 1928: 47.

11 “Saints to Play Reserves,” Cincinnati Enquirer, February 2, 1929: 12.

12 “Johnny Murphy Keeps Promise,” The Tablet (Brooklyn, New York), August 4, 1934: 11.

13 “Panther Baseball Team After Third Title,” Cincinnati Post, March 29, 1929: 13.

14 “Big Leaguers at St. X,” Cincinnati Enquirer, October 1, 1929: 10.

15 In the Boyles’ case, sets of brothers, uncles, and nephews were involved.

16 “Boyle An Important Cog in Oriole Machine,” Evening Sun (Baltimore, Maryland) April 22, 1931: 29.

17 “Draft Season Now Open—Orioles Sell Gill and Boyle to the Washington Senators,” Baltimore Sun, September 15, 1931: 11.

18 “Draft Season Now Open.”

19 C.M. Gibbs, “The SUNdial,” Baltimore Sun, March 5, 1932: 12.

20 “Boyle Named New Lead-Off Man in Revised Batting Order of Orioles-Senators Send Fielder Back,” Baltimore Sun, March 29, 1932: 13.

21 “Omit Flowers,” Baltimore Sun, June 7, 1932: 12.

22 “Slugger Gets Pilots Tips,” Baltimore Sun, March 17, 1933: 10.

23 “Pitchers Busy Chasing Flies,” Baltimore Sun, March 9, 1932: 14.

24 “Bissonette to Baltimore in Exchange for Outfielder Boyle,” Times Union, June 8, 1933: 13. Later in “Veterans All Praise Boyle as Sure Bet,” the Times Union later reported the cash amount was $5,000. The Sporting News reported that the Dodgers gave the Orioles $15,000 plus Bissonette. “Carey Needs Sugar from Leslie’s Bat,” The Sporting News, June 22, 1933: 1.

25 “Dodgers’ Front Office Now Desperate in Quest for New Players–Scouts Scour Minors for First Baseman; Boyle Dons Uniform,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 10, 1933: 12.

26 “Post-Storm Calm Not for the Dodgers,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 19, 1933: 19.

27 “Boyle Looks Like the Find of the Season,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 18, 1933: 16.

28 “Boyle Stars Afield for the Flock’, Times Union, August 27, 1933: 45.

29 “Boyle, Dodger Outfield, Late Season Sensation of the National League,” Times Union; September 19, 1933: 11.

30 “Buzz Playing Great Game After Dismal Start with Dodgers,” Times Union, August 28, 1933: 9.

31 See Endnote 4, above.

32 Harold Parrott, “Sizz-Boom-Ah Debuts-Then the Dull Thud,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, January 28, 1934: 36.

33 Bill McCullough, “Stripp, Boyle Also Get Results with Livelier Pellet in Dodger Workout,” Times Union, March 4, 1934: 15.

34 “Uniform Baseball Adopted by Major Leagues at Conference in Philadelphia,” New York Times, January 6, 1934: 21.

35 Bill McCullough, “Stripp, Boyle Also Get Results with Livelier Pellet in Dodger Workout.”

36 “Postponements Fail to Prevent Drilling of Team in Capital,” Times Union, April 13, 934: 9.

37 “Pitchers Twice Toss Away Big Leads to Drop Twin Bill to Phils—Boyle’s Hitting Streak Broken,” Brooklyn Citizen, June 6, 1934: 6.

38 Interview with Boyle’s grandson Dan Boyle, February 21, 2024.

39 Tommy Holmes, “Dean Brothers Bubbling Over with Fame,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 22, 1934, 6.

40 “Boyle Makes Dean’s Blood Boil.” Journal Times (Racine, Wisconsin), June 25, 1948: 12.

41 “Boyle Makes Dean’s Blood Boil.”

42 “Boyle Covers Batting Sins with Fielding,” Times Union, May 10, 1935: 13.

43 “Cripples and Sulker Few of Woes Heaped on Dodgers Manager,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 6, 1935: 6.

44 “Frey and Boyle Renew Contracts with Brooklyn Dodgers.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, January 21, 1936: 24.

45 “Van Mungo in Form, Kicks on Contract,” The Sporting News, January 30, 1936: 5.

46 “Dodgers in Fast Double Play Snare First Sacker Via Yankees,” The Sporting News, February 27, 1936: 1.

47 “Boyle to Boss Red Farm Club,” Cincinnati Post, January 15, 1947: 18.

48 “New Team to Drill,” Cincinnati Enquirer, May 9, 1943: 34; “Quits Boyle’s Team,” Cincinnati Post, May 12, 1943: 7.

49 “Clocks Win First Game,” Cincinnati Post, June 21, 1943: 11.

50 “Ex-Dodger Star Pilots in Series Here This Weekend,” Atlanta Constitution, May 8, 1943: 17.

51 Interview with Boyle’s grandson, Dan Boyle.

52 “Boyle to Boss Red Farm Club.”

53 Jim Schlemmer, “Buzz Boyle Pilots Girl’s Team,” Akron Beacon Journal, April 17, 1946: 24.

54 Interview with Boyle’s grandson Dan Boyle.

55 “Buzz Boyle Named as Scout by Reds,” Cincinnati Enquirer, November 4, 1947: 18.

56 “Stars Will Greet Old Coach for His 25th Year at Elder.”

57 “Buzz Boyle Quits Reds Scouting Job,” Cincinnati Enquirer, July 27, 1968: 13; “Lawson’s Notes,” Cincinnati Post, June 25, 1965: 20.

58 See the SABR bio of Koufax.

59 Jane Leavy, Sandy Koufax, New York: HarperCollins Publishers (2002): 51.

60 Sandy Koufax, “Sandy’s Dandy Fastball Does It,” excerpt from Koufax autobiography, published in New York Daily News, September 13, 1966: 125.

61 Koufax, “Sandy’s Dandy Fastball Does It.”

62 See the SABR bio of Koufax.

63 “Buzz Boyle Quits Reds Scouting Job.”

64 “Joins Montreal,” Cincinnati Post, August 20, 1968; 17; “Montreal Adds Boyle as Scout,” Cincinnati Enquirer, August 20, 1968: 34.

65 Pat Harmon, “What Worries Spahn Most,” Cincinnati Post, May 22, 1964: 26.

Full Name

Ralph Francis Boyle

Born

February 9, 1908 at Cincinnati, OH (USA)

Died

November 12, 1978 at Cincinnati, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.