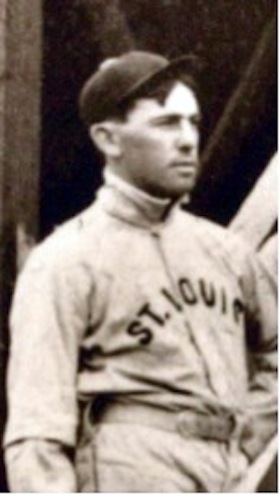

Emmet Heidrick

At the turn of the 20th century, Emmet Heidrick was one of the best players in baseball. A .300 hitter, he could drop a “tantalizing bunt” or drive the ball to the fence.1 As a baserunner and basestealer, he was speedy and aggressive. And as an outfielder, “Snags” was considered “the best fly catcher in the profession.”2 He had exceptional range in center field and a rifle arm. Yet despite these assets, he walked away from major-league baseball at age 28 to focus on his business career.

At the turn of the 20th century, Emmet Heidrick was one of the best players in baseball. A .300 hitter, he could drop a “tantalizing bunt” or drive the ball to the fence.1 As a baserunner and basestealer, he was speedy and aggressive. And as an outfielder, “Snags” was considered “the best fly catcher in the profession.”2 He had exceptional range in center field and a rifle arm. Yet despite these assets, he walked away from major-league baseball at age 28 to focus on his business career.

Robert Emmet Heidrick was born July 29, 1876, in Queenstown, beside the Allegheny River in western Pennsylvania. He was the third oldest of nine children born to Levi Gotlieb Heidrick and Mary Evans “Mollie” Queen. Levi, a son of German immigrants, was a wealthy businessman in the lumber trade during the 1890s.3

Big for the era at 6 feet and 185 pounds, Emmet was a left-handed batter and right-handed thrower. In 1895 he played for the Franklin (PA) Braves of the Class C Iron and Oil League. Among his opponents were brothers Honus and Al Wagner of the Warren (PA) team.4 On August 9, Heidrick contributed a single, double, and two triples in Franklin’s 19-3 rout of Wheeling (WV)5 and attracted the attention of Ed Barrow, owner of the Wheeling team. Barrow acquired the Paterson, New Jersey franchise in the Class A Atlantic League and recruited Heidrick and Honus Wagner to play for the team. Decades later, Barrow would use his eye for talent to build the New York Yankees dynasty.

“Kid” Heidrick was still a teenager when he wowed the Paterson fans in the spring of 1896. He homered in consecutive games against New Haven (CT), May 2-3; went 5-for-5 with three doubles and scored five runs against Newark (NJ) on May 5; and homered against Newark on May 7.6 He made fine catches in left field and threw runners out with a strong, accurate arm. The Wilmington (DE) Morning News declared, “None in the business can beat Heidrick throwing from left field.”7 He batted .299 for the season, while teammate Honus Wagner hit .313.

Paterson won its 1897 season opener at Hartford (CT), and the Paterson Morning Call reported: “Heidrick pulled down a beauty in deep left field that brought the audience to its feet. He got under it after a long run. As it was the third out and two men were on bases, it was a life-saver.”8 At Paterson three days later, “the feature of the game was a catch of a long fly by Heidrick [in left field] and his magnificent throw to first base, completing a double play.”9 It was “one of the finest plays ever seen on the local diamond.”10

After Wagner was promoted to the Louisville Colonels of the National League in July 1897, Heidrick became the most popular player with the Paterson fans.11 He finished the 1897 season with a .334 batting average, 22 triples, and 50 stolen bases. The next year he batted .300 in 45 games12 but left the Paterson team in July for unknown reasons. He played for a semipro club in Atlantic City (NJ) from July to September13 before joining the Cleveland Spiders of the National League in mid-September.

In the first game of a doubleheader at Washington on September 14, 1898, Heidrick singled in each of his first four major-league at-bats.14 He appeared in 19 games for the Spiders in 1898 and hit .303, but his fielding was erratic. Spiders manager Patsy Tebeau said Heidrick is “one of the most natural batters in the country” but must improve his fielding.15

Spiders owner Frank Robison acquired the bankrupt St. Louis Browns in March 1899 and moved the Spiders’ best players, including Heidrick, to a new team called the St. Louis Perfectos. Heidrick quickly won over the St. Louis fans. During the first week of the 1899 season, he “made several sensational catches [in right field] that have astonished the local fans,” and the St. Louis Post-Dispatch said he “throws as well as any man on the team.”16 He slugged his first major-league home run on May 27 in St. Louis, a solo shot off Brickyard Kennedy of the Brooklyn Superbas. Sporting Life called Heidrick “the find of the year.”17 He hit .328 for the Perfectos, scored 109 runs, stole 55 bases (third most in the league), and led the league with 34 outfield assists.

Meanwhile, back in Pennsylvania, Levi Heidrick wished Emmet would quit baseball to help Levi manage his lumber business.18 Emmet loved baseball, but he could please his father and earn more money if he left the game and worked full-time for him. Few ballplayers had any leverage in negotiating with a team owner, but Emmet had leverage and used it. Robison needed this popular young star on his team and could ill afford to lose him. He agreed to Emmet’s demand for a large pay increase, and Emmet returned for the 1900 season.19 His salary rose from $1,500 in 1899 to the league limit of $2,400.20 Emmet would apply this skill in negotiation, no doubt learned from his father, throughout his careers in baseball and business.

Twenty thousand fans packed Robison Field in St. Louis on April 22, 1900, to see Robison’s team, now known as the Cardinals, play Honus Wagner and the Pittsburgh Pirates. All 15,200 seats21 were filled, and an overflow crowd of about 5,000 stood along the periphery of the field. In the top of the ninth inning, Heidrick made two spectacular catches in deep center field, going into the crowd to make the catches. And in the bottom of the ninth, he singled off Rube Waddell and scored the winning run.22

On May 1, Heidrick suffered a leg injury described as a charley horse.23 He tried to play but the injury was serious enough to keep him on the sidelines for most of the next three months. He returned to health in August, and on August 25, he stole four bases and scored both runs in a 2-0 victory over the Chicago Orphans, as Cy Young delivered a shutout.24 Heidrick finished the season with a .301 batting average, but he appeared in only 85 of his team’s 142 games. He would be bothered by leg injuries throughout his baseball career.

The Cardinals tied for fifth place in the eight-team National League in 1900. Furious with his team’s lackluster performance, Robison publicly scolded the players for their “late hours, general debauchery,” and excessive gambling on horse races.25 He leveled his strongest criticism at Heidrick, charging that Heidrick was not truly injured during his long midseason layoff. “I have regretted more than once that this young man didn’t leave us last spring and return to his father’s sawmill,” said Robison. “To him, and to him alone, I blame the loss of third, or even a higher, position in the race.”26 Enraged by Robison’s charges, Heidrick released a written statement from his doctor affirming the extent of his injury.27 Heidrick said, “I defy anyone to prove that I ever drank intoxicating beverages; that I kept bad company or bad hours; that I ever acted save as a gentleman and a ballplayer should.”28

Robison’s diatribe came back to bite Robison. The American League declared itself to be a major league before the 1901 season and elicited a mass defection of players from NL teams. Robison lost Cy Young and catcher Lou Criger to the Boston Americans, while third baseman John McGraw, second baseman Bill Keister, catcher Wilbert Robinson, and outfielder Mike Donlin jumped to the Baltimore Orioles. Heidrick and shortstop Bobby Wallace defected temporarily to the Chicago White Sox,29 but Robison lured the pair back to the Cardinals, presumably by offering a substantial pay raise. This infuriated White Sox owner Charles Comiskey, who threatened to sue Heidrick.30 It was “war” between the major leagues.31

Heidrick began the 1901 season with a bang. In the first six games, he batted .571 (16-for-28) with eight extra-base hits.32 At Cincinnati on May 8, he went 5-for-5 facing Amos Rusie, a future Hall of Famer.33 “For sensational fielding, good hitting and fast base running, Emmet Heidrick of the St. Louis Club ranks at the top among the centerfielders of the league,” reported the Brooklyn Daily Eagle.34

And then on July 20, 1901, tragedy struck the Heidrick family. While retrieving a coat from a closet in his house, Levi upset a loaded shotgun, which discharged into his abdomen, killing him instantly.35 Emmet rushed home to be with his family. He regretted that he had not abided by his father’s wishes, and he considered quitting baseball to help out at home.36 But his father’s business was in the capable hands of Emmet’s older brother Charles, so Emmet returned to baseball. At the time, he led the National League with a .386 batting average.37 He rejoined the Cardinals in Pittsburgh on August 5, and drove in five runs in a 20-6 rout of the Pirates. He finished the season with a .339 average, sixth best in the league.

For a jump in pay, Heidrick and six teammates (Bobby Wallace, Jack Harper, Jesse Burkett, Dick Padden, Jack Powell, and Willie Sudhoff) jumped to the new St. Louis Browns of the American League in 1902. Heidrick had been on the league’s blacklist for reneging on the White Sox the year before, but the league forgave him.38 Robison, left high and dry by the desertion of seven players, went to court to retain three of them (Heidrick, Wallace, and Harper) but lost his lawsuit.39

In St. Louis on June 16, 1902, Heidrick smacked a ninth-inning, walk-off single to give the Browns a 6-5 triumph over the Orioles.40 Ten days later at Cleveland, his four hits were instrumental in his team’s 5-2 victory.41 He returned to Pennsylvania in July, when his mother died after an extended illness.42 Back in St. Louis on August 7, he slugged two doubles and two triples, and scored four runs, in a 12-4 thrashing of the Boston Americans.43 Two days later in St. Louis, he made a catch in center field described as “brilliant in the extreme”; he doffed his cap twice to acknowledge the applause.44 The Browns finished the season in second place, five games behind the Philadelphia Athletics. Though his batting average dropped to .289, Heidrick was a key member of a strong team and was offered a salary of about $5,000 for the 1903 season.45

Generally speaking, ballplayers of this era were an unsavory lot. Heidrick stood out as refined, well-spoken, and well-read. Off the field, the “dapper Beau Brummel” dressed impeccably.46 His wardrobe included a large collection of neckties, stickpins, and whangees (stylish bamboo walking sticks).47 Women adored the handsome (and wealthy) bachelor.

Heidrick hit .280 in 1903 and .273 in 1904 for the Browns, and the team finished a disappointing sixth each season. The decline in his batting average corresponded to a decrease in the league average during these years. On the basepaths, however, he showed no sign of slowing down. Against the Washington Senators on August 15, 1903, Heidrick stretched a single into a double by “a daring dash” and “a very graceful slide” into second base; the play was a “beaut,” noted the St. Louis Republic.48 He was one of the best at the art of sliding, according to New York Highlanders manager Clark Griffith.49 In the second game of a doubleheader on September 17, 1904, the Browns and White Sox were tied 5-5 in the bottom of the 11th inning. Facing pitcher Ed Walsh, Heidrick beat out an infield single, stole second base, and “by a great burst of speed,” scored the winning run on a ball hit into shallow right field.50 He stole 35 bases in 1904, third most in the league.

Ed Barrow managed the Detroit Tigers in 1903 and 1904, and tried to trade for Heidrick.51 “Never mind how far, high or low, a ball was hit to center field, he would catch it if there was the least chance to make a play on it,” said Barrow. “Many a game he has beaten the Tigers while I was handling them, and more than once I have temporarily regretted having found and introduced him to professional baseball.”52

But the Browns were criticized during two straight losing seasons. The St. Louis Post-Dispatch chided the “prima donnas” for their listless performance and said the team has “no support from the public.”53 Browns owner Robert Hedges acknowledged the difficulties. “As a business man, I must make some changes in my team for next season,” said Hedges in August 1904. “Of course Heidrick is a fixture. I would not trade him for any center fielder alive because I consider him the greatest in the business today.”54 But Hedges insisted that Heidrick take a pay cut for the 1905 season, and that did not sit well with the star center fielder.55

Meanwhile, Charles Heidrick needed Emmet to help manage their joint venture, a new railroad in western Pennsylvania. The Pittsburgh, Summerville & Clarion Railroad opened for traffic on August 27, 1904. The 16-mile route for transporting timber and coal, traversed “a large field of undeveloped coal.”56 Emmet had plenty to do in Pennsylvania and chose not to report to the Browns in 1905. He was close-mouthed about his intentions, though, and because he did not declare his retirement from baseball, he may have been holding out for more money from the Browns. But Hedges did not budge, and Emmet remained in the Keystone State. A story appeared in the Washington Post in May 1905, saying that Emmet was engaged to a wealthy woman who requested that he give up baseball,57 but the woman was not identified and he did not marry until three years later. On April 7, 1908, he married Helen Louise Wilson,58 a young woman from a wealthy family.

Heidrick officially announced his retirement from baseball in January 1906. At the time, he was supervising the construction of apartment houses in which he had invested.59 He resided in Clarion (PA) and worked in his railroad office there.60 He still loved baseball and played regularly on local semipro teams, but he turned down several offers to play for major- and minor-league teams.61 “I can’t afford to neglect business interests to indulge myself,” he said.62

Finally, in August 1908, after a four-year absence, the Browns persuaded the 32-year-old Heidrick to return to the team. He homered in his first game back, on August 19, in the first game of a doubleheader at Washington.63 At his first home game, on August 31, he was greeted by “a rousing reception” from the St. Louis fans.64 Four days later in St. Louis, he lined a double over Ty Cobb’s head (“the ball crashing against the right field fence only a foot or two below the top”) in a 4-2 victory over the first-place Tigers.65 The Browns beat the Tigers again the next day to move to within a half game of them, but went 13-17 over the remainder of the season and finished in fourth place.

Described as “overweight and sluggish,”66 Heidrick batted a mere .215 in 26 games in 1908. Nonetheless, the Browns invited him to spring training in 1909, hoping that he would get into shape and return to his former glory. Browns manager Jimmy McAleer said optimistically, “If Heidrick gets back in condition, he will be the best outfielder in the American League, and I haven’t forgotten Ty Cobb and Sam Crawford when I say that.”67 But Heidrick declined the invitation.

Emmet and Helen had two sons born in Clarion, Emmet Jr. in 1909 and Gardner in 1911. Emmet was in charge of coal mines along the route of his railroad, in addition to his lumber and real estate businesses. He continued to play baseball for local teams until he suffered a leg injury in 1913 at the age of 37.68 In May 1912, he recruited Cy Young to pitch for Clarion in a charity game.69

On January 20, 1916, Emmet died unexpectedly of influenza at age 39, in Clarion.70 An obituary in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette details the extent of his business empire. At the time of his death, he was president, owner and operator of two coal companies in Clarion; president of a railway company in Kentucky; director of a Pennsylvania manufacturing firm and a West Virginia lumber company; and co-owner of a telephone company serving several counties in western Pennsylvania.71

Emmet’s business acumen was passed on to his son Gardner, who co-founded Heidrick & Struggles in 1953, one of the first executive recruiting firms. In 2016, the Chicago-based firm was still a leader in executive recruiting. Since 1982, the Association of Executive Search and Leadership Consultants has annually presented the Gardner Heidrick Award to an individual for lifetime achievement in this field.

Last revised: August 28, 2020 (ghw)

Notes

1 Sporting Life, March 11, 1905.

2 Ibid.

3 Ancestry.com; 1880 and 1900 US Censuses; Pittsburgh Daily Post, January 29, 1893; Williamsport (PA) Sun-Gazette, June 29, 1895.

4 Warren (PA) Evening Democrat, August 19, 1895.

5 Philadelphia Times, August 10, 1895.

6 Sporting Life, May 9 and 16, 1896; Paterson (NJ) Morning Call, May 8, 1896.

7 Wilmington (DE) Morning News, August 19, 1896.

8 Paterson Morning Call, April 27, 1897.

9 Philadelphia Times, April 30, 1897.

10 Paterson Morning Call, April 30, 1897.

11 Sporting Life, September 25, 1897.

12 Henry Chadwick, ed., Spalding’s Official Base Ball Guide for 1899 (New York: American Sports Pub., 1899), 111.

13 Philadelphia Times, July 28, August 4, and September 6, 1898.

14 Washington Times, September 15, 1898.

15 Sporting Life, December 17, 1898.

16 St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 17 and 23, 1899.

17 Sporting Life, June 10, 1899.

18 Chicago Inter Ocean, July 21, 1901.

19 Sporting Life, February 3 and 24, 1900; Cincinnati Enquirer, March 5, 1900.

20 Sporting Life, October 27, 1900.

21 Philip J. Lowry, Green Cathedrals (Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1992), 227.

22 Pittsburgh Daily Post, Pittsburgh Press, and St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 23, 1900.

23 St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 2, 1900.

24 St. Paul (Minnesota) Globe, August 26, 1900.

25 Sporting Life, October 27, 1900.

26 Ibid.

27 Pittsburgh Press, October 29, 1900.

28 Sporting Life, November 3, 1900.

29 Minneapolis Journal, March 2, 1901.

30 St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 2, 1901.

31 Chuck Kimberly, The Days of Wee Willie, Old Cy and Baseball War: Scenes from the Dawn of the Deadball Era, 1900-1903 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2014).

32 Sporting Life, April 27 and May 4, 1901.

33 Detroit Free Press, May 9, 1901.

34 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 3, 1901.

35 Pittsburgh Daily Post, July 21, 1901.

36 Chicago Inter Ocean, July 21, 1901.

37 St. Louis Republic, August 4, 1901.

38 Chicago Tribune, October 22, 1901.

39 St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 6, 1902; Minneapolis Journal, June 7, 1902.

40 St. Louis Republic, June 17, 1902.

41 St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 27, 1902.

42 Pittsburgh Press, July 9, 1902.

43 Boston Globe, August 8, 1902.

44 St. Louis Post-Dispatch and St. Louis Republic, August 10, 1902.

45 Pittsburgh Press, December 14, 1902.

46 Sporting Life, March 11, 1905.

47 St. Louis Post-Dispatch, September 13, 1903.

48 St. Louis Republic, August 16, 1903.

49 Washington Post, February 11, 1906.

50 St. Louis Republic, September 18, 1904.

51 Detroit Free Press, May 30, 1904.

52 Washington Post, December 12, 1905.

53 St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 10 and August 7, 1904.

54 St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 18, 1904.

55 St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 2, 1905; Wilkes-Barre (PA) Record, March 11, 1905.

56 William James McKnight, Jefferson County, Pennsylvania: Her Pioneers and People, 1800-1915, Volume I (Chicago: J.H. Beers, 1917), 105.

57 Washington Post, May 22, 1905.

58 Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, April 8, 1908.

59 Boston Globe, January 30, 1906.

60 Harrisburg (PA) Telegraph, May 4, 1906.

61 Pittsburgh Press, March 7, 1906.

62 Washington Times, January 3, 1906.

63 Sporting Life, August 29, 1908.

64 Detroit Free Press, September 1, 1908.

65 St. Louis Post-Dispatch, September 5, 1908.

66 St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 22, 1908.

67 St. Louis Post-Dispatch, February 21, 1909.

68 Pittsburgh Daily Post, July 31, 1913.

69 Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, May 26, 1912.

70 Pennsylvania death certificate.

71 Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, January 24, 1916.

Full Name

R Emmet Heidrick

Born

July 29, 1876 at Queenstown, PA (USA)

Died

January 20, 1916 at Clarion, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.