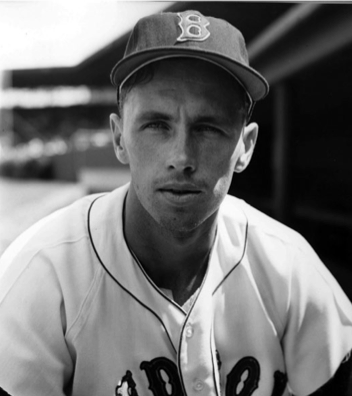

Sammy White

Boston fans who liked the way Jason Varitek handles the Red Sox pitching staff would have loved Sammy White. Sammy, who was selected as an American League All-Star catcher in 1953, was the team’s number one catcher from 1952 to 1959. White was a credible hitter, averaging .264 during his eight full seasons with the Red Sox, but it was his skill behind the plate that earned him a reputation as one of the better major league catchers of the 1950s.

Boston fans who liked the way Jason Varitek handles the Red Sox pitching staff would have loved Sammy White. Sammy, who was selected as an American League All-Star catcher in 1953, was the team’s number one catcher from 1952 to 1959. White was a credible hitter, averaging .264 during his eight full seasons with the Red Sox, but it was his skill behind the plate that earned him a reputation as one of the better major league catchers of the 1950s.

Casey Stengel, who managed the New York Yankees to six American League pennants and four world championships during White’s tenure as the regular Red Sox catcher, was one of Sammy’s biggest fans. Stengel got to see White in action up to 22 times each year under the old 154-game schedule, and he used to shake his head at Sammy’s ability to “frame” a pitch. “He [White] steals more strikes from umpires than anyone else,” Stengel would tell anyone who would listen. “I’m not being critical,” Stengel would add, “I’m just bowing to his skill.”

Former Red Sox pitcher Frank Sullivan has a vivid memory of White’s catching style, and how much it aggravated Stengel. In his book Life Is More Than 9 Innings (Editions Limited), Sullivan writes of White, “He could catch a ball with his palm, heel down, no more than two inches off the ground. Umpires might call it a strike as they figured no ball that low could be caught that way.” Recalling Stengel, Sullivan continued, “Casey Stengel used to holler to the umpires, ‘Get that reptile off his belly.’ ”

Mel Parnell, who won more games (123) for the Red Sox than any other left-hander in the team’s history, has fond memories of pitching to White. “I had some terrific catchers during my career with the Red Sox,” Parnell said, recalling his 10 years with the team. “But I would have to say that Sammy White was the best of them all. He just had a tremendous feel for the pitcher/catcher connection, for the flow of the game. I was always pleased when I knew Sam would be catching me.”

Samuel Charles White was born in Wenatchee, Washington, about 150 miles east of Seattle, on July 7, 1928. He grew up in the Green Lake neighborhood in north central Seattle and he excelled in sports at Lincoln High School. A three-sport star in football (as a fullback and end), basketball, and baseball at Lincoln, he was best known for his exploits on the basketball court. In a comprehensive retrospective of White’s sports career that appeared in the Seattle Times on June 23, 2002, Blaine Newnham wrote, “Sammy White grew up in a one-room house on Aurora near Green Lake. A blanket separated sleeping from eating. But from some such desperate beginnings came an athlete ahead of his time, a rangy kid who could dunk a basketball when it wasn’t yet allowed, who led Seattle’s Lincoln High School to a state championship, and the University of Washington Huskies to the NCAA tournament.” As close as they became as Red Sox teammates and throughout the rest of White’s life, Frank Sullivan said that Sammy never talked about his family. “I was told he grew up in tough circumstances,” Sullivan said.

He also could be a bit of hell-raiser – his actions in breaking up his high school’s senior prom led to his suspension from athletics at the end of his junior year, though he was back starring in time for his senior year. “He was the greatest passer, playmaker, and boardman I’ve seen in 30 years of high-school coaching,” recalled his basketball coach, Bill Nollan. In his final game, he scored 15 points and controlled the backboards in his school’s 50-38 win over Bellingham for the state title.

After a nine-month tour with the Naval Reserve, in 1946 White turned down a few baseball offers, including an $18,000 offer from the Pirates, to enter the University of Washington, where he starred in baseball and basketball. Once more his exploits on the hardwood outshined his achievements on the baseball diamond. Sammy was named to the first-team all-Pacific Coast Conference basketball team in 1947-48 and 1948-49. And he was one of the first future major leaguers to play in the NCAA basketball tournament (NYU’s Sam Mele, future player and manager, was the first), leading his team to the Elite Eight in 1948. White played mainly first base for the college team, but caught in a few semipro leagues in the summer – one of them, the Mt. Vernon Milkmaids, won the state tournament and traveled to Wichita, Kansas, for the semipro national tourney.

But in 1949, White decided that baseball was his best path to a future in professional sports and he left college to sign with the Seattle Rainiers in the Pacific Coast League. Part of his motivation was money – his father had recently died, and his mother was struggling to care for her three children. During the 1949 season, the Boston Red Sox purchased White’s contract from the Rainiers. A longtime friend, University of Washington basketball teammate Lew Morse, recalled how White learned of the transaction. “I remember going to Sick’s Stadium one day,” Morse recalled for the Seattle Times, “and sitting on top of the other dugout was Oakland’s Billy Martin. Billy yelled at Sam, ‘Hey, there goes the $60,000 man,’ and that’s how Sam found out the Red Sox had purchased his contract.” As part of the deal, White received a portion of the sale price. “I told Joe Cronin and Eddie Collins [Red Sox manager and general manager, respectively] that they had another Bill Dickey,” said Rainiers GM Torchy Torrance, “and I don’t think I was far off.”

Despite his impressive hitting in Seattle (.301 average), it was soon clear that White needed to spend some time lower in the minor leagues to learn to catch. After a brief stop in Louisville, the Red Sox sent him to Oneonta, New York, in the Class C Canadian American League. White flew to New York City, and then took a train to (incorrectly) Oneida, where he was told there was no ballpark or team. He called Louisville manager Mike Ryba and had to ask, “What did you say the name of that town was?” He had earned the nickname “The Oneida Kid.”

White hit .356 in 30 games for Oneonta, while also carrying on a letter-writing romance with Sally Jane Mallory, his college sweetheart and a United Airlines stewardess. She came to Oneonta to visit, and “she felt so sorry for me she agreed to marry me.” They tied the knot in New York City on October 3. Their first child, Samuel, was born in 1951, and Kathy and Debbie soon followed.

White advanced the next two seasons to Class B Roanoke (Piedmont League) and Class A Scranton (Eastern League), hitting .258 and .267 while honing his skills as a catcher. After his 1950 season at Roanoke, White tried out with the Minneapolis Lakers of the National Basketball Association.

Former Boston Celtics player Jack Nichols, who was a teammate of White’s at the University of Washington, told the Seattle Times in 1991, “At 6’3” [White] probably could have played small forward in the NBA at that time. He was one of the first guys who could float, like so many of the players do today.” The Red Sox warned White that he could not be late for spring training, while the Lakers insisted that he be prepared to spend the entire season (through April) with the team. In any event, White lost the final spot on the Lakers roster to future Minnesota Vikings coach Bud Grant, who was already a celebrity in the Minneapolis area.

After his season at Scranton, which included rave reviews for his catching ability, Sammy White made his major league debut with Boston on September 26, 1951, against the Senators in Washington. The 1951 Boston Red Sox were only 2½ games out of first place in the American League on September 18, but slumped badly to finish in third place. After the season second baseman Bobby Doerr, who had been plagued by a bad back, retired, and Ted Williams was recalled to active duty by the United States Marines. The Red Sox hired 35-year-old manager Lou Boudreau to begin a “youth movement” to reshape the team. In 1951 the team had used seven different players at catcher, but Boudreau selected Sammy White to provide stability behind the plate in 1952.

In an interview with Sport in 1955, White admitted that he was somewhat raw at the start. “I called the pitches,” he said, “but it was strictly a guessing game. I was nervous and felt I had to argue all the time. I was always saying the wrong thing at the wrong time to the wrong umpire. I gave them all sorts of nonsense, It was pretty stupid of me.” He was thrown out of two games in his rookie year for arguing balls and strikes.

Ted Williams, for one, was appalled at White’s batting stance: legs spread wide and bent over, rump protruded, with his bat held high. “I’ll bet you a hat right now the guy never hits .280,” Williams said. Nonetheless, White rewarded his manager’s faith by batting .281 in 115 games in 1952, while gaining the confidence of the Red Sox pitching staff. Williams eventually came around, though White learned to stand up straighter, move his legs closer together, and bring his arms closer to his body. This allowed him to gain more power as his career progressed.

He first became a Boston fan favorite during a rather bizarre 11-9 victory over the St. Louis Browns on June 18, 1952. The legendary Satchel Paige had come on in relief for the Browns in the bottom of the ninth with St. Louis holding a 9-5 lead. Rookie center fielder Jimmy Piersall, who was in the midst of a bizarre series of behavioral issues that led to a nervous breakdown in July, led off the inning by signaling Paige that he was going to bunt. Piersall bunted successfully and proceeded first to imitate Satchel’s unique delivery, and then to yell and gesture like a monkey as he led off first base. An unnerved Paige gave up two singles and walked two Red Sox players, and when White stepped to the plate the bases were loaded and the Browns’ lead had been cut to 9-7. Sammy hit a game-winning grand slam and celebrated his achievement by crawling halfway home from third base and planting a kiss on home plate. White regretted the incident. “I was struggling like a dog to make the club and I was mighty thrilled with the home run. I remember that by the time I got to third the tension was too much. But that’s still no excuse for crawling home.” On June 23, White showed his power with a home run and four RBIs as the Red Sox defeated the Tigers, 12-6. As the season progressed and White’s strong play continued, he was touted as a candidate to be named the American League’s Rookie of the Year. A mixture of veterans led by Dom DiMaggio, Mel Parnell, and George Kell, together with youngsters like White and power-hitting first baseman Dick Gernert, kept the 1952 Red Sox in contention. On August 27, they were in third place, only 3½ games off the pace.

The 1952 Sox slumped during the balance of the season and finished sixth. White placed third with seven votes for Rookie of the Year, trailing Athletics pitcher Harry Byrd, who got nine votes, and Browns catcher Clint Courtney, with eight votes. The Boston Baseball Writers Association voted White as their co-Rookie of the Year, along with Eddie Mathews of the Boston Braves.

In 1953 Sammy White picked up right where he had left off. He demonstrated that he had improved at the plate, in handling the pitching staff, and with his fists. In the spring he challenged the whole Phillies team in an exhibition game in Roanoke, Virginia. In the middle of a tense duel of hit batsmen, the Phillies players began to yell at Red Sox pitcher Russ Kemmerer. Sticking up for his pitcher, White yelled, “Quit moaning. I called it!” In the second game of the regular season, in Philadelphia, the writers awarded him a TKO victory when he easily outpointed the Athletics’ Allie Clark after a home-plate collision. He also had an early career fight with the Philadelphia’s Billy Hitchcock.

That season White started almost every Red Sox game, appearing in 136 games over the 154-game season. On June 18, White earned a permanent place in the baseball record books during a 23-3 Red Sox shellacking of the Detroit Tigers. The Red Sox scored 17 runs against the Tigers in the seventh inning, and Sammy became the first 20th-century player to score three runs in one inning.

His outstanding first-half play earned White an invitation to the All-Star Game in Cincinnati, where the National League defeated the American League, 5-1. White didn’t play, as American League manager Casey Stengel elected to keep Yogi Berra behind the plate for the entire game.

Pitching in relief against the Chicago White Sox on September 13, with White behind the plate, Frank Sullivan won the first of his 97 major-league victories, as the Red Sox prevailed, 7-6. White’s contribution included a rare play for a catcher: an unassisted double play. In his memoir, Sullivan recalled the role White had in his early success: “I had never thrown to someone with that much grace and agility behind the plate. He was six feet, three inches tall and he could make himself into a two-foot high, one-foot wide block that made the catcher’s mitt look like a barn door,” Sullivan recalled. “When I joined the Red Sox in August 1953, I was somewhat successful, due in large part to Sam. All of the guys I threw to over the years were decent catchers, but I was never as good without Sam.”

Despite strong seasons from pitchers Mel Parnell (21 wins), and Mickey McDermott (18 wins), and good offensive production from White, the 1953 Red Sox were never in contention for the American League pennant. The team finished fourth, 16 games behind the Yankees.

Things got off to a very bad start for the Red Sox on the opening of spring training in 1954, and went downhill from there. Ted Williams had returned from combat in Korea in late 1953, and Red Sox fans were looking forward to his first full season since 1951. But after a few minutes of shagging fly balls on March 1, Williams fell awkwardly on his left shoulder, breaking his collarbone. He was out of the lineup until mid-May.

White was one of the few bright spots for the Red Sox in a dismal 1954 season. He homered on Opening Day in Philadelphia and added a home run two days later as the Red Sox defeated the Washington Senators in the Fenway opener. On May 25, after he had grounded into double plays in his first three at-bats, White’s ninth-inning home run was the margin of victory in the 3-2 win over the Philadelphia Athletics. Over the course of the 1954 season, White caught in 137 games, and increased his production in several important offensive categories. He batted a very respectable .282, and his 14 home runs and 75 RBIs both represented career highs. After three full seasons as the regular Red Sox catcher, White was acknowledged as one of the premier catchers in major-league baseball.

After the 1954 season White got in more hot water when he tried to form a basketball team of major leaguers who would barnstorm around New England. (The Whites had settled in Newton, a suburb just west of Boston.) The Red Sox put a stop to the basketball team, but White would not sign his 1955 contract for a while as a protest. The previous winter he had coached the basketball team at Beverly High School, and believed that his workouts with his boys were more strenuous than a series of exhibitions would have been. Joe Cronin would not budge, and said, “The reason it’s hard to make a trade for this club is that every general manager starts off by asking for White. And now even the basketball general managers are doing it, too.”

In 1955, under new Red Sox manager Mike “Pinky” Higgins, Sammy White was behind the plate for nearly every game. Recognizing White’s value to the pitching staff, Higgins started him in 143 of the team’s 154 games. His 544 at-bats that season ranked tenth in the American League,and first among the league’s catchers. But catching nearly every day took its toll on White’s offensive production. His batting average fell to .261 from .282 the previous season, and his RBI total dropped from 75 to 64, but he did set a career high with 65 runs scored and his 30 doubles ranked fourth in the American League. More importantly, he clearly helped the pitching staff – which featured 10 different starters in the 154 games – to a high level of achievement.

The Red Sox opened the 1956 season at Fenway Park on April 17 with an 8-1 victory over the Baltimore Orioles. The opener featured a very unusual play that involved roommates White and Frank Sullivan. Pitcher Sullivan, who gave up only one unearned run in the Red Sox victory, stepped to the plate with the bases loaded in the third inning. Frank managed a fly ball to right field that was deep enough to allow Jimmy Piersall to score from third base. But White was thrown out after tagging up at first base and attempting to advance to second base. Thus, one of Sullivan’s 22 lifetime RBIs was earned when he hit into a double play.

White had averaged almost 140 appearances behind the plate from 1953 to 1955, and manager Higgins rode him hard in 1956. In fact, Higgins penciled him in behind the plate in each of the first 26 games the team played. As the season wore on, White’s back began to bother him and his hitting continued to suffer. The highlight of the 1956 Red Sox season occurred on July 14 when Mel Parnell threw a no-hitter against the Chicago White Sox in a 4-0 victory. Shortly after Jon Lester tossed his no-hitter against the Kansas City Royals on May 19, 2008, Parnell spoke about the role a catcher plays in a pitcher’s success, and how much he appreciated Sammy White’s contribution.

“I used four different pitches,” Parnell recalled after Lester became the first Red Sox lefthander to pitch a no-hitter since Mel’s gem, “and I always made it a point to throw all four pitches in the first inning. Then I would sit with Sam in the dugout between innings and decide which two of my pitches were working the best that day. Sam had the best feel for the game that I ever saw. I had complete faith in his judgment and he was always right, it seemed.”

The Red Sox finished 1956 a disappointing 13 games behind the New York Yankees. Sammy White’s batting average fell to .245 and he split playing time with Pete Daley during the second half of the season.

In 1957 the Red Sox continued their pattern of winning more than they lost, staying in the middle of the American League pack, and never really contending. The big excitement was Ted Williams’ flirtation with a .400 batting average. On August 25, the 38-year-old Williams had a batting average of .393, and he finished the season at .388. Symptomatic of their subpar season, 11 Red Sox players, including White and Frank Sullivan, were stricken with food poisoning just before a Labor Day doubleheader with the Washington Senators. For the season, White’s batting average dropped to .215 in just 340 at-bats. He managed only three home runs that season, down from a high of 14 in 1954, and his slugging average was a dismal .276.

Little changed for the Red Sox in 1958, but White did show signs of regaining his batting stroke. In 1957, he had started only 105 games behind the plate while Pete Daley started the other 49 games. Manager Higgins continued this pattern in 1958, starting Sammy in only 91 games, and the extra rest paid off in improved offensive production from the veteran backstop. He doubled his home run output to six, he improved his batting average to .259, and he raised his slugging percentage by over 100 points to finish at .378. And no one ever questioned his value to the Red Sox pitching staff.

Sullivan recalled that White had almost a sixth sense when it came to his connection to the pitcher: “Sam would call the first three innings, and if he felt I was in a groove, he would catch me the rest of the way without signs! He just knew what I was going to throw, and I had complete confidence in him.”

After the 1958 season Sullivan agreed to pilot a 42-foot powerboat from Boston to Fort Lauderdale, Florida. Sullivan asked White to join him on the trip, more for his ballast than his seamanship skills. The pair decided that a stop at Tom Yawkey’s private island off the coast of South Carolina would be the ideal way to break up the trip.

Sullivan recalled their warm welcome from Tom and Jean Yawkey, and the dinner that followed. “One drink led to another and the conversation somehow settled around hitting. The next thing I knew, Mr. Yawkey had a broom in his hands and was showing Sam what he thought was wrong with Sam’s swing. I heard Sam tell our host, ‘You may be right, Tom, but if I was that fat I’d never get around to the ball.’” Sullivan added, “I have never been in a room where people sobered up more quickly.”

Whether due to tips from Yawkey or not, Sammy White’s offense continued to improve in 1959. In The Sporting News, Hy Hurwitz noted, “Sammy White continues to hit well and seems headed for that big season that Mike Higgins has been expecting for the past three seasons.” The Red Sox as a team had trouble finding their groove in 1959, and Mike Higgins was fired as the manager on July 3, with the Red Sox in eighth place, 10½ games out of first place.

White’s batting average increased significantly immediately after Higgins’ dismissal. In what Hurwitz described as “strictly a coincidence,” White went 44-for-135 (.326 batting average) during the five weeks following Higgins’ departure. Hurwitz went on to say, “For three years, Mike Higgins, deposed Red Sox manager, kept saying that he saw no reason why catcher Sammy White doesn’t hit .300. With Higgins departed, White seems headed to the exalted group of American League .300 hitters.”

The Red Sox played 44-36 baseball for Billy Jurges, Higgins’ replacement, but finished in fifth place, 19 games behind the White Sox. In what would turn out to be their last year as teammates, Sammy outhit Ted Williams by 30 points, finishing with a batting average of .284 in 119 games, while Ted’s average fell to a career low of .254.

The March 16, 1960, edition of The Sporting News announced that Sammy White was the last Red Sox player to sign his 1960 contract. The article also gave considerable space to White’s business venture, Sammy White’s Brighton Bowl. Frank Sullivan remembered that White didn’t just lend his name to the enterprise. “Sam was very involved in the bowling alley all the way through. He was backed by George Page [of the Colonial Country Club in Lynnfield] and Sam was active in the construction and the operation.” Interestingly, it was when Jackie Jensen returned to help White open the bowling alley that Jensen decided to come back out of retirement and play once more for the Red Sox in 1961. Years later, in September 1980, four workers at the bowling alley were found shot execution-style, when taxi driver Bryan Dyer entered to rob the lanes the moment it opened on a Monday. Dyer was sentenced to five consecutive life terms in prison.

On the same March 16 the Boston Red Sox announced that White had been traded to the Cleveland Indians for catcher Russ Nixon. White promptly announced his retirement from baseball, sitting out the 1960 season to focus on his bowling enterprise. On June 15, 1961, the Milwaukee Braves coaxed White out of retirement and purchased his contract from the Red Sox. Frank Sullivan remembered, “When Del Crandall got hurt, the Braves called Sammy. The Braves paid him something like $35,000 for a partial season, the most money he ever made in baseball.”

In Milwaukee, White backed up the regular catcher, a young rookie by the name of Joe Torre. After appearing in 21 games for Milwaukee, he was released by the Braves at the end of the season. In spring training 1962, Sammy signed on as a free agent with the Philadelphia Phillies, and reunited with his old roommate Frank Sullivan. White started only 31 games for the Phillies, and his baseball career came to an end when he was released on October 19, 1962.

His marriage to Sally, which yielded three children, eventually ended and he remarried Nancy later in his life. In 1964 Sammy rejoined his friend and former batterymate Sullivan on Kauai in Hawaii. The pair originally worked in construction but became certified as golf professionals by the PGA in 1978. Sammy White was the director of golf for the Princeville Resort on Kauai at the time of his death, at the age of 63, in 1991. Lew Morse, White’s old Washington teammate, said it had happened at home, when he took a break from trimming a hedge to have lunch. “Nancy made him a chicken pot pie,” said Morse. “He was having lunch by himself and choked to death.” [Newnham article, op. cit.] He’d fallen asleep on a couch after eating and then choked.

In 1980, Sammy White was inducted into the State of Washington Hall of Fame in recognition of his baseball career. He was voted into the Husky Hall of Fame of the University of Washington for baseball and basketball in 1984.

Sammy White’s lifetime batting average with the Boston Red Sox was .264. And if you speak with the Red Sox pitchers who threw to him, they will tell you that he was as good behind the plate as anyone they ever saw.

Sources

Mel Parnell, telephone interview with Herb Crehan, May 2008.

Frank Sullivan, Life Is More Than 9 Innings (Honolulu, Hawaii: Editions Limited, 2009).

The Sporting News

Jack Newcombe, “Boston’s Cocky Catcher,” Sport, August 1955.

Gerry Hern, “The Pepper Pot,” in Tom Meany [editor], The Boston Red Sox (A.S. Barnes, 1956).

Full Name

Sammy Charles White

Born

July 7, 1927 at Wenatchee, WA (USA)

Died

August 4, 1991 at Princeville, HI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.