Floyd Giebell

On September 27, 1940, the Detroit Tigers were in Cleveland to start a three-game series against the second-place Indians. The Tigers had a two-game lead in the pennant race, so one win in the series would bring a league title back to Detroit. But Cleveland was starting off the set by sending the top pitcher of the era to the mound — Bob Feller. To oppose Feller, Detroit manager Del Baker selected Floyd Giebell, a little-known 30-year-old making only his second appearance of the season. Indeed, the righty had turned pro only two years before and had reached the majors for just nine games in 1939.

On September 27, 1940, the Detroit Tigers were in Cleveland to start a three-game series against the second-place Indians. The Tigers had a two-game lead in the pennant race, so one win in the series would bring a league title back to Detroit. But Cleveland was starting off the set by sending the top pitcher of the era to the mound — Bob Feller. To oppose Feller, Detroit manager Del Baker selected Floyd Giebell, a little-known 30-year-old making only his second appearance of the season. Indeed, the righty had turned pro only two years before and had reached the majors for just nine games in 1939.

Giebell was given one job to do: basically put a warm arm on the mound and keep the game respectable for the Tigers as they took their lumps from Feller. Then they would come back and try to seal the pennant in one of the next two games with one of their regular starters. Instead, Giebell pitched the game of a lifetime, a six-hit shutout. Afterward he was hoisted off the field on the shoulders of his teammates. For years Giebell’s name brought a cringe when mentioned to Indians fans. To this day he is still listed among Tiger heroes of the past.

In many baseball accounts this is where Giebell’s story comes to an end. His name would appear occasionally in “This Day in Sports” articles, and these pieces usually highlighted that after his pennant-clinching victory he never won another major-league game.

Giebell even received mention in the July 1951 issue of Esquire magazine, as author John P. Carmichael, in his article entitled “One Crowded Afternoon,” pondered whatever happened to the one-time wonder pitcher who seemingly dropped off the face of the earth. But Giebell’s baseball career went on long after that 1940 game, extending through years of service to his country, community, and family.

Floyd George Giebell Jr. was born on December 10, 1909, in Pennsboro, West Virginia. Floyd’s middle name changes between George, Carl, and Karl when looked up in various sources. The reason is a mystery even to direct family members. He was the first of four boys born to Floyd N. and Ora Giebell.

The elder Floyd was the son of German immigrants. Besides running the family farm, he also worked at a lumber mill in the area. His father, Conrad, served his adopted country by joining the 155th Regiment of the Pennsylvania Infantry for the Union in the Civil War before settling in Pennsboro.

The younger Floyd started out playing baseball the same way many kids of his era did, by throwing a ball up against the walls of his family farmhouse or aiming for holes in the barn. Giebell attended Pennsboro High School, where he stood out on the school team both as an outfielder and on the mound.

After finishing high school, Giebell went to work to help support his family. His father had been involved in a workplace accident, so Floyd devoted his time to working and tending to the farm. Four years later Giebell enrolled at Salem College (now Salem University) in nearby Salem, West Virginia. There he worked toward a business degree and played on the varsity baseball and basketball teams.

Giebell was older than much of the competition he faced while at Salem — many students were four years his junior. Whether purposeful or based on assumptions from the year he graduated, Giebell’s age was mislabeled throughout his career. Various articles from 1940 noted his age as 26, 25, or getting ready to turn 25, when he was already past 30 years old. As Dennis Snelling notes in his chapter on Giebell for his book, A Glimpse of Fame, it was quite common for baseball players of the day to have a “playing age” that wouldn’t turn scouts away.

But his age in school shouldn’t diminish the feats Giebell accomplished for the Salem College Tigers. Besides starring in baseball, both as a left-handed batter and as a right-handed pitcher, he also captained the men’s basketball team. Years later he was named to the West Virginia Intercollegiate Athletic Conference all-time teams for both sports. In 1992 he was inducted into Salem University’s athletic hall of fame, and as of 2020 he was the school’s only graduate to appear in the major leagues. In addition to these accolades, he also received invaluable experience when Salem played exhibition games against local professional teams, including most notably the legendary Homestead Grays of the Negro Leagues.

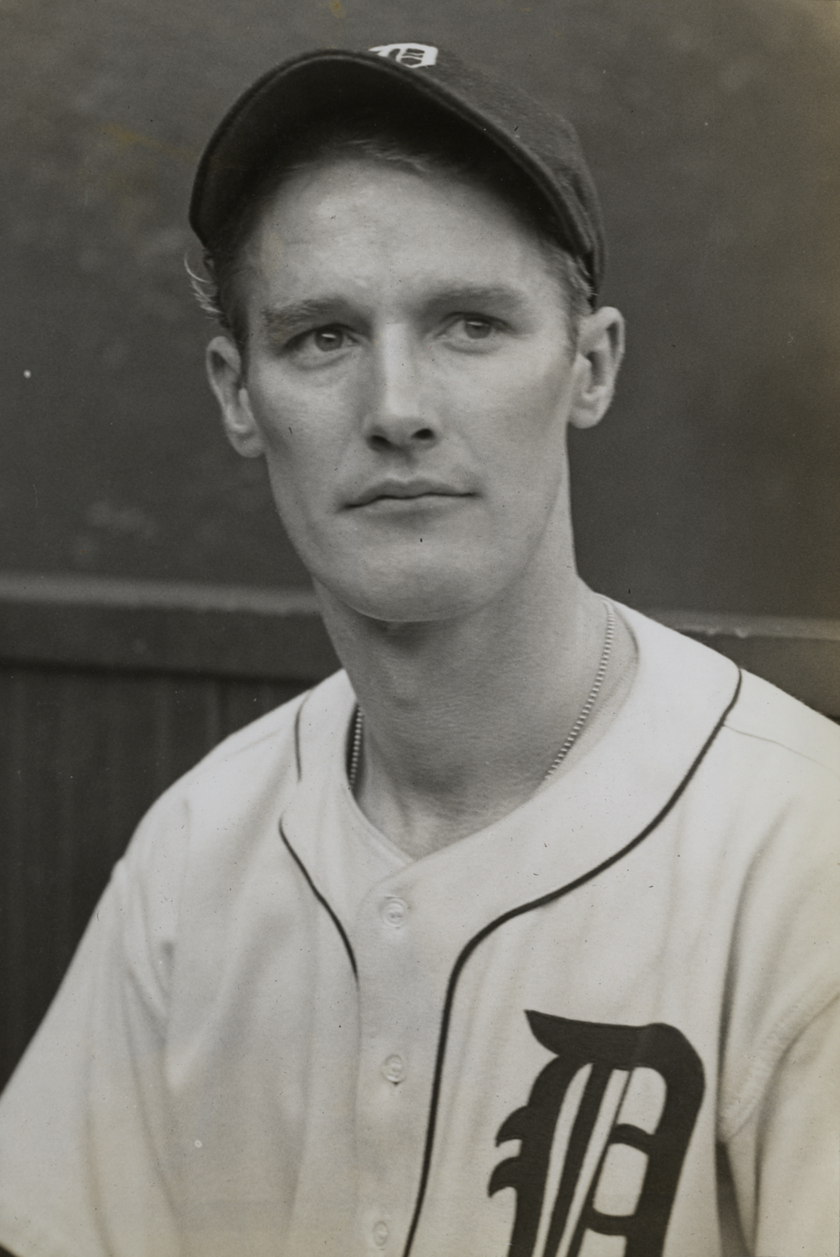

Once while attending a Salem College girls softball game, Giebell couldn’t take his attention away from the young lady playing first base for Salem, a student in the teaching program named Helen Mae Button. Giebell was tall and lanky, standing 6-feet-2 and staying around 175 pounds during his playing days. He had sandy blond hair and blue eyes, and he was very quiet and typically kept a low profile. Later, at his first major-league spring-training camp, Giebell made the front page of the sports section of the Detroit Free Press when photo captions joked that he had finally been witnessed talking. But the normally soft-spoken Giebell apparently had no trouble approaching Helen. The two were later engaged and eventually married, and they stayed together over 60 years.

Floyd’s parents had relocated to Holliday’s Cove, West Virginia, and during his summer breaks from college, Giebell worked nearby for the Weirton Steel Corporation. That company was at one time among the world’s largest steel producers, and the community of Weirton was built around the factory. The steel plant was large enough that it supported its own baseball league for its employees, with teams representing the various work departments. Employees and baseball fans in the town closely followed their department teams, and game results were highlighted in local papers. Mike Naymick of the Cleveland Indians and Frank Kalin of the Chicago White Sox were also alumni of the Weirton Steel baseball league.

Giebell worked in the strip steel section of the plant and was the top pitcher for the department’s team, even though he preferred batting to pitching. In September 1937 Giebell led a team of Weirton players to victory at the National Amateur Baseball Federation championship in Dayton, Ohio, beating out top amateur teams from all over the Eastern part of the country. Giebell started the championship game on one day’s rest and “turned in a sterling performance” against a Dayton team playing with a home-field advantage.1 The annual tournament regularly drew major-league scouts in to view some of the top unsigned talent in the country. Billy Doyle, the longtime scout for the Tigers who discovered Hank Greenberg, was among the scouts in attendance. After the tournament he signed Giebell for the Detroit organization. The Reds had also offered Giebell a contract, but they wanted him to go straight to prospect camp. Detroit made an offer that allowed him first go to back home and help out on the farm for the rest of the year before reporting to camp.

For his first professional spring training in 1938, Giebell was assigned to the Beaumont Exporters of the Class A1 Texas League, but to start the season he was farmed to the Evansville Bees of the Class B Three-I League. Evansville was actually a farm team for the Boston Bees (Braves), but they had a rotation spot open and Detroit wished for Giebell to work under the tutelage of Evansville’s manager, former major-league catcher Bob Coleman. Giebell again may have been playing against younger competition, but nonetheless he was dominant against other teams in the league. After starting off the year with 10 wins against only one loss, Giebell was a unanimous choice for the league’s Southern Division all-star team. He finished the 1938 season with an 18-6 record, tying with Emil Bildilli for the league lead in wins and leading the Bees to the Three-I league pennant. He also topped the league with a 1.98 ERA and 23 complete games.2 By coincidence, one of Giebell’s teammates in Evansville was Bob Feller’s cousin, pitcher Hal Manders.

The following season Giebell was slated to attend spring training with Beaumont again, but Coleman recommended to the Tigers that he was ready to try out for the major-league squad.3 When 1939 Opening Day arrived, Giebell had made the roster (30 men to start the season) and traveled north with the team. He made his major-league debut on April 21 against Cleveland; as it happened, Bob Feller was on the mound for the Indians. Giebell entered the game in the eighth inning and had two strikeouts (the first against Feller) in a successful debut.

However, the Tigers began planning moves to meet the May 15 25-man-roster deadline, and Giebell was one of the first players sent down. The announcement that he’d been optioned to Beaumont came on April 29.4

Giebell was shuttled between the majors and minors during the year. He started off well in the Texas League with four straight wins before being called back up to Detroit on June 23. Giebell earned his first major-league win on July 6 in a relief effort against the Browns. After appearing in four more games in relief, he was sent back to the minors, this time to Toledo of the Double-A American Association. George “Slick” Coffman had originally been announced to be getting demoted so that top pitching prospect Fred Hutchinson could join the team, but Coffman demanded to be traded and Giebell was sent instead.5

Giebell ended up with a disappointing record in the American Association, losing 10 games versus only one victory, but a fair portion of that record can be attributed to a poor Toledo team. Giebell had a decent year statistically speaking, finishing 16th in the league with a 3.58 ERA. He wasn’t overpowering (37 strikeouts in 93 innings) but had good control (21 walks). He was recalled to the majors in September and appeared in two more games in mop-up duty against the Yankees and then the Indians.

Although Giebell didn’t spend much time in the majors in 1939, he witnessed the year’s most memorable baseball moment. On May 2 he was on the bench for the Tigers when Lou Gehrig walked the lineup card for the Yankees to the umpires and it was announced that Gehrig’s streak of 2,130 consecutive games played had come to an end. Giebell later provided vivid memories of this day to Dennis Snelling, as well as Jonathan Eig, author of the Gehrig book Luckiest Man. One may infer that even though his assignment to Beaumont had been announced a few days before, he was still with the big club for part of Detroit’s homestand, although further evidence confirming when he traveled south has not surfaced. As Texas newspapers show, Giebell pitched for Beaumont no later than May 6.6

Giebell was invited back to Lakeland for spring training in 1940 but got off to a very slow start. An article in The Sporting News made mention of a sore arm; another article from the same paper attributed his woes to a sore back. In actuality Giebell was still recovering from severe blood loss following a routine tonsillectomy. He had made it to Florida for the start of spring training, but was not yet back at full strength after the procedure.

After some rough spring outings, Giebell was optioned to the Buffalo Bisons of the International League. He’d have preferred to start the season in the majors but was optimistic about possibly starting regularly in Double A. After reporting to Buffalo’s spring camp, Giebell made a good impression on skipper Steve O’Neill, a former longtime catcher in the AL, and he was named Opening Day starter for the Bisons.

That first start on April 18 was a rough one for Giebell, and it proved to be just the beginning of a frustrating season. Giebell did have 15 wins that year, just meeting a $1,000 bonus goal, but his 17 losses tied him for the league lead. At least 10 of those defeats were by one run. Giebell was normally very composed, but he was also quietly a fierce competitor. After a third one-run loss in a row during one stretch, he picked up a fungo bat on the way to the clubhouse and smashed out every light in the passageway.7

But manager O’Neill knew that Giebell had pitched better than his record showed, commenting that Giebell “pitched in 40 games, and there were only two bad ones.”8 Giebell also led the International League in runs and earned runs allowed, but despite his pedestrian numbers he was called back up to the majors in September. O’Neill had suggested to Del Baker that Giebell would be helpful to have down the stretch. He called Giebell the kind of pitcher that batters like to hit against, saying they “won’t do a lot to him, although they won’t be able to wait until they get up to the plate.”9 And with a big series in Cleveland on the horizon, O’Neill suggested that Giebell “would be at his best in a big ballpark, where the outfielders have room to move around.”10

Giebell returned to Detroit, and after a doubleheader on September 18, he was called on for a spot start the next day against the Athletics in the first game of another twin bill. Even if it was against the worst team in the league, he still had a solid performance, pitching a complete game in a 13-2 victory.

Giebell’s next start would go into baseball annals. The Tigers needed just one win to capture the flag, but if the Indians could sweep, they would overtake the Tigers and win the pennant. The Tigers had just gone through their three front-line starters, Schoolboy Rowe, Tommy Bridges, and Bobo Newsom. Rowe was next in line to pitch, but Baker half-forfeited the game to Feller in advance, opting instead for either Giebell or 19-year-old rookie Hal Newhouser. There are several variations to the story of how Giebell was selected to pitch that day, but they all agree that leading up to the game Baker met with veteran members of the team and asked for their input regarding who should get the start in game one. Baker was leaning toward Giebell, and the team backed his decision.

Before the game Giebell was spotted warming up in the bullpen, and journalists in the press box had to make a mad dash to figure out who the mystery pitcher was. Some spectators in the stands thought Giebell warming up was a ploy to throw off the Indians — or even a joke. “They thought the real starter was somewhere under the stands,” Giebell recalled in 1972. “They were certain Baker was up to something and I was just a decoy.”11

But Giebell had indeed been tabbed as the “sacrificial lamb” versus Feller. Over 45,000 Cleveland fans showed up for the ladies day game, and they were more than a little disappointed to find out that Rowe would not be pitching that day. Detroit and Cleveland had a nasty rivalry that extended to their fans, and the Tigers were the target of all sorts of flying debris leading up to the start of the game. After a barrage of fruit and trash in the first inning, umpire Bill Summers announced that one more outburst would result in the Indians forfeiting the game, and the crowd finally settled down. Through this commotion, Giebell had remained composed and focused on the mound. There’s still no telling how his middle initial came to be K, but it was said it stood for Kalm that day.12

Giebell had been described as a hitter-friendly pitcher, in that batters loved to see his pitches but had a hard time actually doing anything with them — and that’s exactly how the game went for the Indians. He scattered six hits and two walks, and though he found himself in trouble a few times during the game, the “Icicle Kid” remained unflustered each time and escaped without damage. Feller allowed only three hits, but one was a two-run homer by Rudy York. That was all the offense Detroit managed — but it was all that Giebell needed.

As soon as Jeff Heath grounded out for the last out of the game, the Tigers swarmed upon Giebell and carried him off the field. As they celebrated their title win in the clubhouse, journalists started searching for this unknown pitcher who had seemingly come out of thin air and just outdueled the best pitcher in the world. They found Giebell sitting quietly by his locker, silently absorbing what had just happened. “They thought I should be up and whooping it up and turning lockers over. I didn’t feel that way. … Something had been accomplished that I’d … that most boys had dreamed about.”13

Unfortunately for Giebell, players added to the roster after September 1 were not eligible for the postseason. So despite his pennant-clinching heroics, Giebell was not able to take part in the World Series against the NL champion Cincinnati Reds. The Tigers approached Reds manager Bill McKechnie and he graciously allowed Giebell to suit up and sit on the bench with his Tigers teammates for the Series and toss batting practice. Giebell was voted a $500 share at the conclusion of the Series, which Cincinnati won in a seven thrilling games. He also came away from it with high praise from Baker, who reportedly told him, “You would have been my starter in Game 3 if I could have used you.”14

Newspaper articles later chronicled how Tigers owner Walter Briggs showed Giebell his appreciation by promising him a full share of the Detroit players’ World Series winnings, making up the difference out of his own pocket. Briggs also reportedly arranged to have Helen, then Giebell’s fiancée, come see the Series. Stories like this endeared Briggs to the fans of Detroit, but they may not have been true. Years later for his interview in Snelling’s book, Giebell said he did receive a $1,000 bonus, but not the full Series share,15 and he wired money to Helen so she could come to the Series.

Even so, Giebell came away with mementos from the season. His friend York took the bat that he had used to hit the homer in Giebell’s win, and had it signed by the team for him. His most cherished prize, though, was a sterling silver plate that he received from the fans of Detroit, as did all the Tigers players.16 It was adorned with the likeness of owner Briggs surrounded by the engraved signatures of his Tiger teammates.

Giebell’s sudden popularity carried into the offseason. He was invited to be the guest speaker at several events across the Eastern United States, including a dinner ceremony sponsored by the Dayton Amateur Baseball commission, the group that sponsored the NABF tournament in which Giebell had starred just three years earlier. By the time Giebell got ready to show up for spring training 1941, he’d spoken to crowds as many as 13 times.17

Heading into that season, Giebell was expected not only to make the Tigers roster out of spring training but also to step up and be part of the starting rotation. He was looking forward to the coming year since his supporter Steve O’Neill was joining the Tigers staff as a coach. A number of sports journalists did not see how the Tigers could repeat as AL champions for 1941, but Giebell and Newsom were among the team members who spoke out expecting the team to win the pennant again.

But the Tigers started off the year sluggish. After a six-game losing streak in early May, they were in fifth place, seven games behind first-place Cleveland. Age was catching up with Bridges, Newsom, and Rowe, and young hurlers Newhouser and Johnny Gorsica didn’t quite take the step forward that Baker was hoping for. Giebell may again have been dealing with a lame back and possible shoulder issues coming out of spring training;18 he got off to an especially slow start. After starting an exhibition rematch against Feller in March, he made just five regular-season relief appearances through May.

In early June Rowe was moved to the bullpen and Giebell was given a chance to start, but after being driven out early in two straight games, he was sent back to the pen. Through July Giebell had been used sparingly in relief and had not factored in a decision, and his season ERA sat at 6.29.

On August 8 Giebell started in an exhibition game against the Flint Indians, a Cleveland farm club in the Class C Michigan State League. The Tigers lost, although they may have not used their full big-league squad for the game, and Flint — which sported future major leaguers Gene Woodling and Steve Gromek — was the top team in the league. Still, the Tigers could have reasonably been expected to defeat a team from the lower rungs of the minors.

As early as June, Giebell had already approached Detroit general manager Jack Zeller about being traded so he could play more regularly.19 The Flint game may have finally convinced Zeller he should do that. The next day Giebell was sold outright to Buffalo, never to return to the majors.

But despite his step back, Giebell was happy to have a chance to be part of a starting rotation again. In his first appearance with the Bisons, Giebell defeated Rochester, which featured young Stan Musial. His season also concluded on a high note as he and Helen Mae were married that September.

The United States’ entry into World War II pulled many ballplayers into duty with the armed services or in war work. Giebell was initially ruled ineligible for service because he was considered the primary means of support for his parents.20 His status was later changed to make him eligible for the draft, but in 1942 Floyd and Helen welcomed their first child, daughter Sterling Ann. Thus, he was changed back to non-eligible. Giebell did his part for the war effort, though, working during the 1941-42 offseason in a Buffalo defense plant. Floyd and Helen had taken a liking to that city, and he signed on to play with the Bisons again for the 1942 season.

In early May of that year, Giebell suffered a fractured jaw while taking fielding practice before a home game. He was admitted to Buffalo General Hospital and was to be kept there for at least four days for observation, but two days into his stay, the hospital was surprised to find that Giebell had departed. He reportedly left a note saying, “I am leaving; give this bed to someone who is really sick.”21

Though Giebell considered himself healthy enough to go AWOL from the hospital, he didn’t pitch again for nearly three weeks after the injury. He finished the season with a respectable 3.69 ERA and eight wins, including one in a much-hyped August matchup against former Detroit teammate Schoolboy Rowe, then with the Montreal Royals (a Brooklyn Dodgers affiliate).

Giebell was welcomed back in 1943 to pitch another season for the Bisons. But with the war effort ramping up, his draft status was reclassified during the year to 1A and he was called back for another draft board examination. He did finish the season for Buffalo, winning 12 games against 17 losses, but that November Giebell was officially called to service and inducted into the US Coast Guard.

Giebell was assigned to the Coast Guard training station at Curtis Bay in Maryland. Like most US military units of the time, Curtis Bay had a baseball team, the Cutters, which competed in the Eastern Service League. Its East Coast location made the station easily accessible for exhibition games against both major- and minor-league teams. It wasn’t uncommon for the Cutters to beat the pro squads, thanks to a formidable lineup featuring the likes of Giebell, Mickey Witek of the New York Giants, longtime major leaguer Hank Majeski, and two-time All-Stars Hank Sauer and Sid Gordon.

Giebell stayed in Curtis Bay for the duration of his service time, serving aboard the Coast Guard cutter Pontchartrain. He was honorably discharged in October 1945.

Giebell returned to Buffalo for the 1946 season eager to resume his career after losing two years to military service. He made one appearance in his return to the Bisons, but new Buffalo manager Gabby Hartnett was focusing on making the team younger, and Giebell was released. He promptly signed with league rival Syracuse and finished the season with the Chiefs, but his contract was not renewed for the 1947 season.

That offseason Giebell signed with the Dallas Rebels of the Texas League, where he was reunited with Al Vincent, his manager during his first stint in Buffalo. Giebell played for two seasons in Dallas, but by the 1948 season he was 38. Giebell’s family had grown in February 1947 with the birth of his son, Floyd Stephen, and he didn’t want his children moved around from city to city, year after year. As much as he’d appreciated the chance to make a living as a baseball player, he’d seen too many other men try to hang on in the minors, missing time with their families, or even losing them, as they were constantly on the road. “I saw ball players taking their families around … taking their children out of school … and bringing them up for the season. And I said that’s never going to happen to me,” he said.22

On June 21, 1948, Giebell started the game for the Rebels and pitched them to victory over Shreveport. Immediately afterward, he announced his retirement. Giebell had been offered a position as athletic administrator for the Woodside Cotton Mill in Greenville, South Carolina. Dallas persuaded him to stay on through the end of the season, which he did, but then the Giebells headed to the textile region of the Southeast.

As West Virginia and Pennsylvania had steel leagues, South Carolina had a thriving baseball scene with a multitude of textile factory-based leagues. Woodside had what at one point in the twentieth century was the largest textile mill in the world. Though the textile leagues were formed around town mills, they were also considered independent minor leagues, where young players could work their way up to more advanced levels while “working” at the factories. The leagues also provided a means for some former major leaguers to get a chance to play ball once again, the most famous example being Shoeless Joe Jackson.

Giebell was placed in charge of Woodside’s athletic programs, including baseball, basketball, track, and any sports that could be made available to the mill’s employees. Among his duties was managing the Woodside Wolves baseball team in the Western Carolina Textile League, the same team Jackson had managed and played for in 1937. Giebell guided the team to a league title in 1950 while also serving as one of its starting pitchers. During his time at Woodside, Giebell also coached men’s and women’s basketball teams, added a softball program, helped his wife start a nursery for employees’ children, built new playgrounds, and assisted in an undertaking to construct a new gym and community center.

After three years at Woodside, Giebell moved to Great Falls, South Carolina, where he took a similar but scaled-back position with Republic Mills. This move appears to have closed the book on Giebell’s playing career. He managed the Republic team but there is no indication that he played for it.

After six years in South Carolina, the Giebell family returned to Weirton. Floyd rejoined the Weirton Steel Corporation and worked in its quality control department until his retirement in 1972. He had no regrets moving on from baseball and the Giebells were happy to finally be resettled near family in West Virginia. But this phase of their life had a sorrowful moment. In November 1969, Floyd and Helen received the devastating news that their 22-year-old son, Floyd, had been killed in action during the Vietnam War. Sgt. Floyd Stephen Giebell had just entered the Army the year before after working along with his dad at Weirton Steel. He had been recognized as the top artilleryman in his graduating class at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, and had achieved the highest grades ever made in military strategy at Camp Gordon, Georgia.23 He was posthumously awarded the Military Merit Medal and the Gallantry Cross with Palms, and awarded a Good Conduct Medal, Bronze Medal, Air Medal, and a Purple Heart.

Not long after the death of their son, the Giebells retired near Naples, Florida. But once again wanting to be near family, they eventually relocated to Wilkesboro, North Carolina, to be close to their daughter, Sterling, and her family.

In April 2004, Floyd Giebell died at the age of 94. He’d been the first born of his four brothers but ended up the last survivor. Helen, his wife of over 62 years, lived another two years before her death in 2006. Both are buried in Scenic Memorial Gardens in Wilkesboro.

In 2001 Giebell’s win over Feller for the 1940 pennant was ranked 17th on the Cleveland Indians all-time 100 worst moments of their first 100 years.24 As recently as 2016, Bill Livingston of the Plain Dealer in Cleveland still “recognized” Giebell by placing him on his list of Detroit’s Dirty Dozen, along with the likes of noted enemies of Cleveland such as NBA players Bill Laimbeer and Dennis Rodman.25

Yet for as long as he lived, Giebell regularly received letters from fans, reminding him how much his effort in that one game in September 1940 still meant to them so many years later. He always made sure to get out his typewriter and personally respond to each one. He also received the occasional request from authors or journalists wishing to visit and interview him for various publications. When they did, he made sure to show them his cherished gift from that season: the silver platter from the appreciative fans of Detroit.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Len Levin and fact-checked by Bill Johnson.

Photo credit: Detroit Public Library, Ernie Harwell Collection.

Sources

The author thanks Floyd Giebell’s daughter, Ms. Sterling Tomlin, for taking the time to help fill in some gaps, and generally sharing memories of her parents (phone interview, July 2020).

The author relied on Dennis Snelling’s interview with Giebell from his book A Glimpse of Fame for much of the information on Giebell’s life before and after his baseball career.

Johnson, Lloyd, and Miles Wolff, eds. Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball (Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America, Inc., 1993).

Kelley, Brent. The Pastime in Turbulence, (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2010), 41-50.

Wancho, Joseph. “Tigers clinch American League pennant behind Floyd Giebell,” SABR Games Project: https://sabr.org/gamesproj/game/september-27-1940-tigers-clinch-american-league-pennant-behind-floyd-giebell/.

Perry, Thomas K. Textile League Baseball: South Carolina’s Mill teams, 1880-1955 (Durham, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 1993).

Snelling, Dennis. A Glimpse of Fame, (Durham, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 1993), 183-200.

The author used the following websites for research: baseball-reference.com, newspapers.com, paperofrecord.com, newspaperarchive.com, ancestry.com, scpictureproject.org (for history of Woodside Textile Mill), wikipedia.org (for history on USCGC Pontchartrain), nps.gov/civilwar/soldiers-and-sailors-database.htm (for military record of Conrad Giebell), cleveland.com for Detroit’s Dirty Dozen article.

TheSABR Guide to Minor League Statistics, 3rd Edition, was used to check several of Giebell’s minor-league statistics.

The Baseball Hall of Fame provided the player file for Floyd Giebell.

Baseball Digest magazine archives.

Notes

1 “Weirton Tossers Crowned Champs,” Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, September 20, 1937: 22.

2 “Giebell Tops Pitchers,” The Dispatch (Moline, Illinois), October 24, 1938: 15.

3 Charles P. Ward, “Ward to the Wise,” Detroit Free Press, March 9, 1939: 17.

4 “Tigers Send Giebell to Beaumont Club,” Des Moines Register, April 30, 1939: 22.

5 Charles P. Ward, “Tigers Trade McCoy and Coffman to A’s for Wally Moses,” Detroit Free Press, December 12, 1939: 15.

6 “Beaumont Exporters Win from Dallas Rebels, 2-1,” Abilene (Texas) Reporter-News, May 7, 1939: 10.

7 Brent Kelley, The Pastime in Turbulence, (Durham, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2010), 46.

8 Vince Agul, “Tigers’ 1940 Pennant-Clincher: Game of His Life,” Detroit Free Press, September 23, 2003: 2.

9 H.G. Salsinger, “Giebell, Who Pitched Tiger Flag-Clincher, ‘Icicle Kid’ with Cooling System for Batters, The Sporting News, March 13, 1941: 5.

10 Salsinger.

11 Vince Agul, “Floyd Giebell … One Brief Brush with Fame,” Detroit Free Press, September 30, 1972 (from Hall of Fame Player File).

12 Dillon Graham, “Detroit Looks to Rookie for Help,” Associated Press, April 2, 1941.

13 Dennis Snelling, A Glimpse of Fame, (Durham, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 1993), 194.

14 Agul, “Tigers’ 1940 Pennant-Clincher: Game of his Life.”

15 A full share for a player on the losing team in 1940 was $3,531.81. baseball-almanac.com/ws/wsshares.shtml.

16 Kelley, 49.

17 Judson Bailey, “Yankees and Cards Draw 5,119 Fans,” Associated Press, March 9 1941.

18 Sam Greene, “Tiger Infield and Outfield Holes Plugged, but Hurling Goes Blooie,” The Sporting News, June 5, 1941: 5 (back problem); Greene, “Detroit Pitching Starts After Starter Departs,” The Sporting News, July 3, 1941: 1 (sore shoulder).

19 Snelling, 195.

20 Charles P. Ward, “Ward to the Wise,” Detroit Free Press, December 10, 1940: 17.

21 “Injured Giebell Flees Hospital,” New York Daily News, May 3, 1942: 83.

22 Snelling, 196.

23 “Giebells Receive Award of Son,” Weirton (West Virginia) Daily Times, December 21, 1970: 15.

24 “The Tribe’s Worst Moments,” Chronicle-Telegram (Elyria, Ohio), April 2, 2001: 1.

25 Bill Livingston, “Detroit’s Dirty Dozen (+1): Reasons Why We Loathe That Place,” cleveland.com, April 20, 2016.

Full Name

Floyd George Giebell

Born

December 10, 1909 at Pennsboro, WV (USA)

Died

April 28, 2004 at Wilkesboro, NC (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.