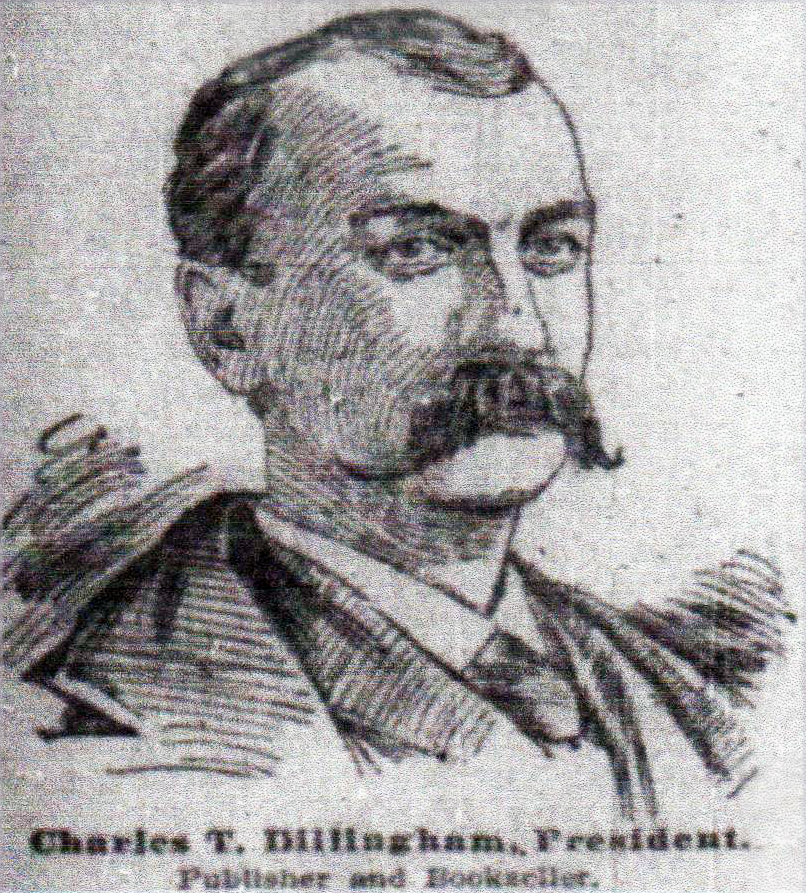

Charles T. Dillingham

Gentlemanly Charles T. Dillingham was the least visible member of the Metropolitan Exhibition Company, the closely held corporation that owned and operated New York’s major league ball clubs during the 1880s. He kept a low profile as a board director of the New York Giants and his views on baseball rarely found their way into newsprint. Indeed, from the outside it appeared that Dillingham was a nonentity, his principal function being to accompany MEC boss John B. Day to National League meetings.

Gentlemanly Charles T. Dillingham was the least visible member of the Metropolitan Exhibition Company, the closely held corporation that owned and operated New York’s major league ball clubs during the 1880s. He kept a low profile as a board director of the New York Giants and his views on baseball rarely found their way into newsprint. Indeed, from the outside it appeared that Dillingham was a nonentity, his principal function being to accompany MEC boss John B. Day to National League meetings.

This contrasted sharply with the esteem in which Dillingham was held by those in his chosen profession: book publishing and distribution. In August 1891, the New York Sun described our subject as “the leading jobber [wholesale bookseller] in the United States, a smart, active and energetic businessman.”1 Ironically, this encomium was contained in a front-page announcement of the financial failure of Charles T. Dillingham & Company. Although he soon had to liquidate his business, Dillingham hung onto his slice of Giants ownership for a few more years. He finally left the board in April 1896 and withdrew from the game, having tendered 15 years of useful, if uncelebrated, service to baseball in New York. Dillingham spent the next two decades in obscurity, dying quietly in 1918 at age 75. The ensuing paragraphs provide the details of his life.

Charles Theodore Dillingham was the embodiment of the 19th century’s self-made man, rising from modest roots to fortune and renown, at least for a time. He was born on December 7, 1842, in Bangor, Maine, a small northern New England manufacturing hub situated 235 miles northeast of Boston. Charley (as he was known to family and friends) was the second of four children born to Theodore Heald Dillingham (1806-1858), a tradesman whose Maine ancestry predated the Revoulutionary War, and his second wife Susan (née Beverage, 1812-1873).2 The death of his father ended Charley’s schooling at age 15. Shortly thereafter, he left for Boston where he found a position as a clerk with a publishing firm.3 By 1860, Dillingham was living and working in New York City.

At the outbreak of the Civil War, Dillingham briefly paused his advancement in the publishing industry for a three-month tour of duty with the New York Seventh Regiment infantry but saw no battlefield action. Once mustered out, he returned to book publishing in Manhattan. In due course, he rose to become a name partner in the publishing houses of Felt & Dillingham (dissolved 1870) and Lee, Shepard & Dillingham.4 He also returned to military service, enlisting in the Seventh Regiment National Guard and serving as recording secretary for the regiment’s alumni association.5 In April 1873, Charley took Frances (Fanny) Pease as his bride. Thereafter, the births of Lee (1875), Alice (1877), and Shepard (1879) completed the Dillingham family.

In February 1875, Dillingham was elected to the executive committee of the Publishers’ Central Organization, a consortium composed “of all the leading publishers in New York, Philadelphia and Boston.”6 Also elected to the committee was Walter S. Appleton, agent for the Manhattan publishing firm D. Appleton & Company and a future MEC cohort. That October, Dillingham bought out his partners and recommenced business as Charles T. Dillingham & Company.7 Although the new concern remained active in publishing, wholesale bookselling was the firm’s forte. Decades later, his obituary noted that although Dillingham “belonged distinctly to the old [conservative] school of booksellers … he mastered the new conditions of changing times successfully and his success in book distribution was marked.”8 The following year, he took over the business of the Boston bookselling firm of James R. Osgood & Company, prompting a distant newspaper to observe that “Mr. Dillingham is known as one of the most enterprising wholesale booksellers of New York.”9

In July 1878, Dillingham was among the noted New Yorkers in attendance at the funeral of Walter Appleton’s father, the distinguished publisher George Swett Appleton.10 In addition to their occupation in the bookselling trade, Walter and Charley were ardent baseball fans, a mutual passion that would shortly manifest itself in ball club investment. In the meantime, Dillingham became active in New York City Republican Party politics. But a fall 1880 bid for a state assembly seat by the “self-made man” was unsuccessful.11

In May 1883, it was reported that “Charles T. Dillingham, the newly elected second lieutenant of Company D, Seventh Regiment, NGSNY, was presented with a set of full dress equipment” at a regimental meeting.12 By now, New York City dailies regularly carried advertisements and book reviews for the latest offerings of Charles T. Dillingham & Company. Curiously absent, however, from Gotham newspaper pages was mention of Dillingham’s association with the Metropolitan Exhibition Company, the organization that sponsored New York’s fledgling major league baseball clubs.

Although there is no evidence that Dillingham was ever a ballplayer himself, as a fan of the game he took a keen interest in the New York Metropolitans, a newly formed independent professional nine that made its way from a Brooklyn start to Manhattan in September 1880. Whether or not Dillingham or his friend Walter Appleton were then personally acquainted with fellow NYC businessman John B. Day is unclear. According to former New York Mets second baseman–turned–New York City sportswriter Sam Crane, Dillingham and Appleton were induced to invest in the MEC by Mets manager Jim Mutrie, rather than by Day.13 Whatever the case, the two booksellers became ground-floor minority shareholders in Day’s baseball venture.

The story of how Day near-simultaneously placed the New York Mets in the major league American Association and the New York Giants14 in the National League for the 1883 season can be found elsewhere.15 The point to be made here is that the rare notice of Charles T. Dillingham’s connection to the ball clubs was confined almost entirely to Sporting Life. In November 1883, the baseball weekly first published what would become its standard mention of Dillingham — namely, that he accompanied New York Giants club president John B. Day to the postseason meeting of NL club owners, and nothing more.16

From its inaugural season on, the Giants board of directors included Dillingham. In the immediately ensuing seasons, however, it was the MEC’s other ball club making most of the stir.17 In 1884, the Metropolitans captured the American Association pennant. During the offseason, the club was stripped of manager Jim Mutrie and stars Tim Keefe and Dude Esterbrook in order to bolster the Giants, the MEC’s favored side. After the denuded and demoralized Mets plummeted to seventh place in 1885, the club was sold to railroad magnate Erastus Wiman who promptly relocated the team to Staten Island.

Charles T. Dillingham played no visible role in any of these events. Apart from regular newspaper advertisement for the wares of his company and the odd review of one of its books, the only time Dillingham’s name saw newsprint was when he accompanied Day to a National League meeting18 or resigned his Seventh Regiment commission.19 That began to change, however, when threats to the Polo Grounds’ existence emerged in early 1888. The Giants ballpark had been a constant irritant to the inhabitants of its tony Central Park North neighborhood. And now friendly forces in city government were pushing a plan to complete the area transportation grid by running a street through the Polo Grounds outfield. An affidavit from New York Giants “Vice-President Charles T. Dillingham” was among the pleadings filed by the MEC in rearguard legal action instituted to forestall condemnation of the ballpark.20 All to no avail. The Giants would need a new home in 1889. In the meantime, the MEC celebrated the club’s 1888 NL pennant and subsequent World Series victory over the AA champion St. Louis Browns.

In January 1889, Dillingham was re-elected vice president of the Stationers Board of Trade.21 He then disappeared from public view as the Giants — playing in a newly constructed far north Manhattan ballpark with a roster that included six future Hall of Famers22 — encored as National League and World Series champions. But a pall was cast over celebration by the announcement that an ominous new rival, the player-owned-and-operated Players League, would be taking the field for the 1890 season. Given that the circuit was the brainchild of visionary Giants shortstop John Montgomery Ward and that teammates Tim Keefe, Roger Connor, and Jim O’Rourke were among its most vocal promoters, the Giants were likely to be hit hard by player defections.

In a preemptive move apparently designed to legally bar the Players League from using the name New York for one of its clubs, Dillingham and others connected to MEC filed a certificate with the New York Secretary of State incorporating the “New-York Baseball Club of New York City” in early October 1889.23 Confusion arose, however, when John B. Day incorporated “The New York Club” immediately thereafter. But the specter of dissention in MEC ranks was thereafter dismissed by Day, as he and Dillingham remained “on friendly terms.”24 Dillingham concurred in that sentiment, backhanding the rumor that Day was interested in allying with the Players League in New York. “There is not a word of truth in it,” declared Dillingham. “Nor do I believe that there is going to be a brotherhood club in [New York] next year. There has already been too much said on that subject. If the players really have any grievances, they will be given a chance to state them at the next meeting of the League.”25

Badly mistaken about Brotherhood intentions, Dillingham was among the MEC brass attending court sessions wherein attempts to enjoin Giants players from jumping to the Players League were rejected. As a result, only aging hurler Mickey Welch and outfielder Mike Tiernan remained in the NL Giants fold. Most of the others signed with the Players League New York Giants.26 With a far better-drawing competitor playing literally only feet away in newly erected Brotherhood Park,27 the MEC soon found itself in financial distress. By July, the situation had become dire, with only an emergency infusion of cash by other NL club owners saving the Giants from bankruptcy. The introduction of these new partners into the club’s operation, however, initiated events that would soon lead to the MEC’s liquidation.

Over the near term, Charles T. Dillingham clung to his normal routine of seeing to his bookselling business and attending intermittent meetings of the National League. Both operations, however, were headed in the wrong direction. After the bloodletting of the 1890 season, MEC boss Day and Players League counterpart Edward B. Talcott agreed to the merger of their Giants ball clubs. In January 1891, their consolidated franchise was reorganized under the laws of New Jersey, with the new organization assuming the title of the National Exhibition Company,28 the corporate handle that the New York Giants would retain for the duration of club existence. Dillingham was among the Day loyalists appointed to a numerically balanced club board of directors, but in reality, Talcott and his allies were now in charge of Giants affairs. By the end of the 1891 season, the portion of club stock held by Day, Dillingham, and their former MEC cohorts had been reduced to a mere 16 percent.29

Far worse for Dillingham than his reduced stake in baseball club ownership was a nosedive suffered by his commercial interests. Although times in the publishing industry had recently grown hard, the business community was stunned by the August 1891 announcement that Charles T. Dillingham & Company had failed, its debts assumed by creditors. Outstanding liabilities were placed in the $150,000 range.30 Dillingham himself attributed the business collapse to “dull trade, low prices, strong competition, and lack of capital.”31 But his lawyer placed the blame on “heavy losses incurred” by Dillingham in propping up the fortunes of the Giants. Allegedly, the club director had “sank close to $100,000” into the ball club.32

This assertion drew a sharp rejoinder from Sporting Life: “Who that knows anything about baseball believes that Mr. Dillingham lost anything like $100,000 in the New York club! The club had but two unprofitable seasons, if attendance figures are to be believed, and in those two years losses would not have been so heavy as to cause a single stockholder to drop such an amount so claimed.”33 Indeed, less than two years earlier the New York Times asserted that MEC principals had “cleared about $750,000” in the then less-than-ten years of the corporation’s existence.34 While this figure seems wildly inflated — only one MEC club is known to have reported a single-season profit as high as $50,00035 — baseball had nevertheless provided Day, Dillingham, and the others with a handsome income stream through 1889.36 The failure of Charles T. Dillingham & Company, therefore, more likely resided with the causes cited by its namesake.

In any event, Dillingham was not giving up his slice of the Giants. To the contrary, reported sportswriter George H. Dickinson, “Mr. Dillingham … expects to arrange his financial affairs so that he can retain his stock in the club.”37 This was in baseball’s interest, added Dickinson, as the genial and conciliatory Dillingham “held the balance between the competing factions” on the Giants board of directors.38

The windup of the Dillingham bookselling business entailed disposing of “the large store of books” in the company inventory. Assisting in this exercise was erstwhile MEC comrade Walter Appleton,39 his own fortune dissipated by indolence, an ex-wife’s extravagance, and the loss of his baseball income.40 Dillingham attempted to stay in the bookselling business, forming a partnership with a nephew, but this endeavor failed, as well.41 Despite these setbacks, Dillingham retained the esteem of professional colleagues, being chosen as president of the Booksellers and Stationers Provident Association in the mid-1890s.42 He completed his working life as an associate in “the well known house of Roberts Brothers.”43

Similar regard attended his relationship with the Giants co-owners. Dillingham was liked and trusted by both the ascendant Talcott faction and his old MEC colleagues, and was retained on the club board of directors at the annual owners meetings as others came and went.44 He even survived the arrival on scene of tempestuous new Giants boss Andrew Freedman in January 1895. Dillingham withdrew from the club directory in April 1896, but held on to a small share of Giants stock, likely as a keepsake.45

Notwithstanding the vicissitudes of the publishing/bookselling business, Charley and wife Fanny enjoyed a mostly comfortable life, ensconced in a luxurious Manhattan brownstone acquired in April 1891.46 In May 1906, however, the couple was distressed by report that a lifeless body pulled from the East River was that of their son Lee. Happily, the report proved false.47

Late in life, Charles Theodore Dillingham retired to Great Barrington, Massachusetts. He died at his home there on October 29, 1918,48 aged 75. The obituary in his Maine birthplace newspaper declared that “as a friend his loyalty was proverbial and his death will mean great loss to his many friends in this city.”49 Following funeral services, the deceased’s remains were interred in Hudson City Cemetery, Hudson, New York. Survivors included his widow and three adult children.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Natalie Montanez and fact-checked by Paul Proia.

Sources

Sources for the information imparted above include US and New York State Census data and other governmental records accessed via Ancestry.com, and newspaper articles cited in the endnotes.

Notes

1 “Charles T. Dillingham Fails,” New York Sun, August 7, 1891: 1.

2 Brother Albert was two years younger. Two other siblings (Harriet and Henry) did not survive infancy. Charley also had two older half-brothers, Edwin (born 1832) and George (1835) from his father’s first marriage to the late Angela Miller Dillingham (1812-1839).

3 Per the Dillingham obituary published in the Bangor (Maine) Daily News, November 2, 1918: 15.

4 Same as above. See also, “Publisher Charles T. Dillingham,” Library of Congress publisher record #29375, accessible online.

5 Per “Circular,” New York Herald, May 29, 1876: 10. Dillingham’s progression through the ranks of his unit is recounted in “National Guard Gossip,” New York Times, February 22, 1885: 4.

6 See “Publishers’ Central Association,” New York Herald, February 10, 1875: 11.

7 As reported in “New York City News,” Pomeroy’s (New York) Democrat, October 23, 1875: 8; “New York and Vicinity,” Albany Argus, October 19, 1875: 1; “Lee, Shepard & Dillingham,” New York Commercial Advertiser, October 18, 1875: 4.

8 “Chas. T. Dillingham,” Bangor Daily News, November 2, 1918: 15.

9 “Literary Gleanings,” Buffalo Commercial, May 16, 1877: 1.

10 See “Funeral of George S. Appleton,” Brooklyn Eagle, July 11, 1878: 4.

11 See “The Political Campaign,” New York Evening Post, October 27, 1880: 3. See also, “The IIId Assembly District,” New York Times, October 31, 1880: 7.

12 Per “City News Items,” New York Herald, May 24, 1883: 3. An ink drawing of 2d Lt. Dillingham in full uniform is viewable on the New York Historical Society website.

13 See “A Bit of History,” Sporting Life, February 5, 1893: 14.

14 Originally nicknamed the Gothams or Maroons but more often identified simply as the New Yorks, the club was not known as the Giants until the 1885 season. For purposes of clarity, however, the club will be referred to as the New York Giants throughout this profile.

15 See e.g., the Bio-Project profile of John B. Day.

16 See “The National League,” Sporting Life, November 28, 1883: 2.

17 According to his obituaries, Charley’s cousin and fellow bookseller Horace E. Dillingham (1849-1889) served as Mets club treasurer. See “Horace Edward Dillingham,” Portland (Maine) Daily Press, December 10, 1889: 2; “Obituary,” New York Tribune, December 9, 1889: 7.

18 See e.g., “Baseball Legislation,” New York Herald, November 19, 1885: 6; “From Chicago,” Sporting Life, October 7, 1885: 5; “Arranging the League Games,” New York Times, March 8, 1885: 2.

19 See “Changes in the National Guard,” New York Tribune, April 5, 1885: 3.

20 “The Polo Grounds Menaced,” New York Herald, June 12, 1888: 8.

21 Per “New York City,” New York Tribune, January 18, 1889: 10.

22 Buck Ewing, Roger Connor, Tim Keefe, John Montgomery Ward, Mickey Welch, and Jim O’Rourke.

23 As reported in the New York Tribune, October 3, 1889: 3. See also, “New York Club Incorporated,” St. Louis Republic, October 5, 1889: 6; “New Name for the New York Club,” New York Evening World, October 5, 1889: 3. The other incorporators of the new club were Walter S. Appleton, Horace E. Dillingham, John T. Walker, and MEC lawyer George F. Duysters.

24 Per “What’s in the Wind, Anyhow?” New York Herald, October 11, 1889: 8.

25 “Will Stand with the League,” Boston Herald, October 6, 1889: 18.

26 Defectors to the PL New York Giants included the Cooperstown-bound Ewing, Connor, Keefe, and O’Rourke, plus second baseman Danny Richardson, third baseman Art Whitney, outfielder George Gore, and utility infielder Gil Hatfield. Ward, meanwhile, assumed command of the Players League club in nearby Brooklyn.

27 The New Polo Grounds home of the NL New York Giants and Brotherhood Park base of the PL New York Giants sat on the same piece of real property and were separated by only a ten-foot-wide alley and the ballpark walls.

28 As reported in “New York Club Affairs,” Sporting Life, January 31, 1891: 3.

29 According to George H. Dickinson, “New York Comment,” Sporting Life, October 17, 1891: 3. Talcott and his allies controlled 44.5 percent of club stock while the remainder was spread out among other National League club owners and a few random shareholders.

30 As reported in “C.T. Dillingham Assigns,” New York Herald, August 7, 1891: 11; “Charles T. Dillingham Fails,” New York Sun, August 7, 1891: 1; “Publisher Dillingham Fails,” New York Evening World, August 6, 1891: 1.

31 “Charles T. Dillingham Fails,” above.

32 Per “Baseball Beats Books,” New York Herald, August 8, 1891: 8.

33 “Dillingham’s Failure,” Sporting Life, August 15, 1891: 1.

34 See “An Offer for the Giants,” New York Times, September 6, 1889: 3, reporting MEC rejection of a $200,000 offer for New York Giants made by Polo Grounds landlord James J. Coogan.

35 The Giants reported a $50,000 profit in 1885, per Orem, 202.

36 A more plausible estimate put MEC profits at about $300,000. See “Western Magnates Fear Treachery,” Philadelphia Inquirer, January 20, 1895: 24.

37 George H. Dickinson, “New York News,” Sporting Life, August 22, 1891: 2.

38 Same as above.

39 Per “Personal Mention,” Sporting Life, February 20, 1892: 2.

40 For more on Walter S. Appleton, consult his Bio-Project profile.

41 Per “Chas. T. Dillingham,” above.

42 See “A Splendid Institution,” New York Times, February 2, 1896: 26.

43 “Chas. T. Dillingham,” above.

44 See “New York’s Club,” Sporting Life, February 17, 1894: 3, noting Dillingham’s reelection to the board at the annual NEH meeting held in early 1894.

45 Per “News and Comment,” Sporting Life, April 4, 1896: 5.

46 Purchased for $22,750, the “Charles T. Dillingham House” at 320 West 88th Street stands to this day and can be viewed online via the Daytonian in Manhattan website.

47 See “Not C.T. Dillingham’s Son,” New York Evening Post, May 17, 1906: 3; “Mystery in Identity of Drowned Man,” New York Evening World, May 17, 1906: 4. Concern was generated when a card found on the deceased’s body bore the name of an alias adopted by elder son Lee, long estranged from his parents.

48 Per “Chas. T. Dillingham,” Bangor Daily News, November 2, 1918: 15, and the death notice published in the New York Tribune, November 3, 1918: 14. October 30 is the date of death published in the New York Times, October 31, 1918: 3.

49 “Chas. T. Dillingham,” above.

Full Name

Charles Theodore Dillingham

Born

December 7, 1842 at Bangor, ME (US)

Died

October 30, 1918 at Great Barrington, MA (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.