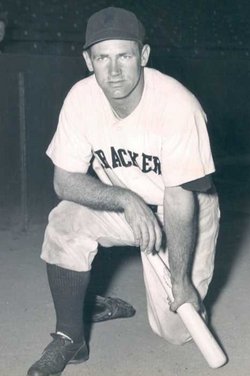

Connie Creeden

Connie Creeden’s life in baseball was defined by two events seven and a half years apart. The first gave him a solitary moment of major-league glory. The second tarnished his reputation and sent him to prison.

Connie Creeden’s life in baseball was defined by two events seven and a half years apart. The first gave him a solitary moment of major-league glory. The second tarnished his reputation and sent him to prison.

On May 2, 1943, at Philadelphia’s Shibe Park, Creeden’s ninth-inning pinch-hit single drove in the winning run in the first game of a doubleheader as his Boston Braves beat the Philadelphia Phillies, 3-1. Creeden, a hard-hitting, lefty-swinging outfielder, made five pinch-hitting appearances that April and May after making the Boston team’s war-depleted roster. This was his only hit.

In November 1950, Creeden pleaded guilty to sexually assaulting a 12-year-old boy in Superior, Nebraska, where he had played that season as a member of the Superior Knights of the Nebraska Independent League.1 A local newspaper reported that Creeden used his baseball fame, as well as his musical talent, to ingratiate himself with families.2 He was sentenced to 10 years in state prison and served almost four before he was granted parole in October 1954.3 He subsequently adopted a new name, Lee Burton, and supported himself as a musician.4

The complicated story of Cornelius Stephen Creeden began on July 21, 1915, in Danvers, Massachusetts, a town on the Atlantic Ocean about 21 highway miles north of Boston.5 According to US Census information and online genealogical records, he was the ninth of 10 children born to Irish-American shoe factory worker John Creeden and his wife, the former Ella Crosby.6

The young man almost didn’t make it out of Danvers. In November 1931, he was operated on for appendicitis.7 Two months later he fell while hunting and shot himself in the stomach. The Boston Globe reported that he was in grave condition, adding that two other boys had been killed in similar incidents.8 And in October 1932, he suffered an unspecified football injury that was serious enough to require hospitalization and cause him blackouts.9 Despite these early mishaps, Creeden grew into a multi-sport athlete with a strapping build. Baseball-Reference lists his adult height and weight as 6-foot-1 and 200 pounds; news articles late in his career placed him as high as 6-foot-3 and 250.10

The young Creeden also honed a wide-ranging talent as a pianist and organist. He played in minstrel shows and amateur musical events in Danvers, and at one point the manager of a theater in town engaged him to perform on its organ. He also sang in a family quartet with three of his brothers.11 Years later a sportswriter was astonished to watch the veteran slugger park himself at a hotel organ and play continuously for an hour, moving effortlessly from hymns to classical to barrelhouse, all without using sheet music.12

On the Fourth of July 1932, not quite 17, Creeden coordinated youth sporting events for Danvers’ Independence Day celebration.13 Youth coaching and counseling, like piano playing, became a recurring thread in Creeden’s adult life. At various times during his baseball career, he was reported to be the football and basketball coach at Falmouth (Massachusetts) High School;14 football coach at Morgan Preparatory School in Petersburg, Tennessee;15 associate headmaster and athletic director at Burritt Preparatory School for Boys in Spencer, Tennessee;16 athletic director at St. John’s Military Academy in Los Angeles; and a coach at the Flintridge School of Pasadena, California.17

For a professional athlete, this pattern of offseason employment seems natural enough. For a man subsequently convicted of abusing a child, it raises eyebrows – and questions about how he behaved in these roles. On one hand, the fact that Creeden held positions of authority over children doesn’t prove that he abused that authority. The author of this biography found no evidence that Creeden was publicly accused of abuse before 1950.18 On the other hand, childhood victims of abuse have sometimes been tacitly or explicitly intimidated out of reporting it; they may also feel shame or repress painful emotions. Thus, the absence of earlier public charges is not an ironclad guarantee that no abuse or grooming occurred.

It would seem like a relief to move from those muddy ethical waters back to the clear-cut world of athletic glory … except that Creeden’s post-Danvers High sporting activities are somewhat clouded as well. He was reported at various times to have played football at Boston College and to have graduated from St. Mary’s College in California, a football powerhouse in the 1920s and 1930s.19 Creeden is not listed on BC’s all-time roster of football lettermen,20 and St. Mary’s has no record of his graduating.21 Archive searches of the Danvers Herald, Boston Globe, and other Massachusetts newspapers turned up no local-boy-made-good stories about Creeden’s college career, and his US Army enlistment record from 1940 lists his educational level as four years of high school. It is possible that journalists mistook Connie Creeden for Patrick “Paddy” Creeden, a star halfback at Boston College in the late 1920s and team captain in 1929.22

We know from the Danvers newspaper that Creeden was in town playing amateur baseball in 1935.23 His first big break came the following year, when he impressed Red Sox chief scout and Boston baseball legend Hugh Duffy in a Fenway Park tryout and at a game in Ipswich, Massachusetts.24 The Red Sox signed Creeden for 1937 and assigned him to a Class D affiliate in Mansfield, Ohio; he lasted there until late May and was released, reportedly for his poor fielding.25 He caught on with a semipro team in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, and fared better there, compiling a .433 batting average in 58 at-bats.26

The following summer found him in the semipro Cape Cod League, where he made the loop’s unofficial season-ending all-star team and earned raves as “a slugger from the word ‘go’ and a ‘natural’ if there ever was one.”27 One writer noted his “tremendous shoulders and powerful wrists” and his speed to first base, as well as a strong but sometimes erratic throwing arm.28

The following three seasons, 1939 through 1941, found Creeden continuing to excel in semipro play29 but making no progress in the minors. His Sporting News contract card has him drawing releases in 1939 and 1940 from minor-league teams in Sydney Mines, Nova Scotia; Wilmington, Delaware; and Saginaw, Michigan.30 Creeden enlisted in the US Army’s Quartermaster Corps in October 1940. He was listed as single without dependents, and his civilian occupation as stenographer and typist.31 According to news stories, he received an honorable discharge from the Army the following year due to the lingering effects of an earlier neck injury suffered on the football field.32

As a 26-year-old with multiple minor-league washouts on his resume, Creeden needed a dramatic turnaround in 1942 to prolong his pro career. He found his chance in Bradford, Pennsylvania, where he wrangled an opportunity with the Braves’ Class D farm club in the Pennsylvania-Ontario-New York (PONY) League as draft-eligible ballplayers marched off to World War II.33 Facing pitchers who were, on average, six years younger than he was,34 Creeden hit .355, set a loop record with 118 RBIs, and broke five batting records of the Bradford team.35 Off the field, he played piano at season-opening receptions in Bradford and Olean, New York, attended by Hall of Famers Branch Rickey and Cy Young and Olean manager Jake Pitler, formerly a Pittsburgh Pirates infielder and later a Brooklyn Dodgers coach.36

Sold to the Braves’ top farm club in Hartford for 1943, the knockabout outfielder reported to spring training with the big-league team, held at The Choate School in Wallingford, Connecticut. Creeden gave news writers a colorful story amid the wintry, mainly indoor setting, which was compelled by wartime travel restrictions.37 They reported not only on his piano playing but also on his off-season employment as a Pinkerton detective.38

With outfielders Nanny Fernandez and Max West gone to the military,39 manager Casey Stengel had roster spots to fill. The piano-playing Pinkerton was a clear defensive liability, but his hard hitting won him a roster spot as a left-handed pinch-hitting specialist.40 For example, in late March Creeden sidelined Braves pitcher Nate Andrews with a line drive off his pitching hand.41 In regular season play, Creeden went 1-for-4 in five appearances between April 28 and May 5. After driving in the winning run in the first game of the May 2 doubleheader against the Phillies, he was intentionally walked in the 12th inning of the second game.42 Stengel sent in a pinch-runner for him in both games.

Creeden’s brief trip to the top of the baseball world ended on May 13. Braves general manager Bob Quinn received a request for an outfielder from a minor league team in Nashville, Tennessee. Creeden was deemed the most dispensable and was ordered to report there, with a significant cut in pay. After a brief debate with Quinn about whether he could field well enough to stay in the majors, Creeden refused to go to Nashville and was suspended.43 Released by Boston, he signed with Utica of the Eastern League within the week, then was sold to Hollywood in the Pacific Coast League in late July.44

Between 1944 and 1950 Creeden continued to play in the minors and independent leagues. However, the most notable aspect of this part of his career as a ballplayer is his unusual fondness for going absent without notice. Creeden’s Sporting News contract card is peppered with references to him being suspended or declared ineligible.45 “He has been fined, suspended, and what not many times in the last few years. When he decides to do a hop, he hops,” one newspaper reported after Creeden left the Atlanta Crackers of the Southern Association in August 1945. “You never know what he is going to do when he scrambles out of his uniform.”46

Even the hometown Danvers Herald, which had often hailed his talents, tut-tutted him in 1947 after he failed to show up for a game in the Class B Colonial League: “Ever one to make the headlines, but not with regard to batting records, Creeden … is still pursuing his age-old precedent of breaking rules but not records.”47

The most baffling of these incidents took place in June 1948 when Creeden was playing for the Florence (South Carolina) Steelers of the Class B Tri-State League. Creeden took a permanent flyer from the team on June 2 – the day after the Steelers’ general manager, Ed Weingarten, received a lifetime ban from organized baseball as part of an investigation into bribery, gambling, and game-throwing. “[Creeden] has a past dotted with several unannounced departures,” one paper noted.48 Weingarten had signed Creeden from the House of David team the month before. The obvious inference from Creeden’s sudden departure was that he was somehow involved in game-fixing, but it was reported that he was hitting .346 at the time he left.49

Two days later, an unnamed “Florence source” provided a reporter with a baroque explanation of Creeden’s departure. It had nothing to do with the gambling investigation, the source asserted. Rather, Creeden was reported as being 39 years old and having trouble seeing the ball at night, so he had gone to Quebec to play semipro ball in daylight.50 In truth, he was a month shy of 33 – although the part about going to Quebec was accurate. Creeden hit a rousing .430 that season with St. Hyacinthe of the independent Provincial League. Shaving a few years off one’s age to seem younger is an old ballplayer’s dodge, but Creeden must be one of relatively few players to add years to his age for his own benefit.51

As it happened, Creeden had used a similar excuse after jumping the Atlanta team in August 1945. He gave a reporter an even more exaggerated age, while also saying he had to leave baseball to begin fall coaching duties at the Morgan Preparatory School in Tennessee. “I’m 40 years old now,” he said, although he was only a month past 30. “My legs can’t take it like they used to. My future is in coaching. I like it at Morgan – a fine school – and have a chance to stay there. I’m going to do that.”52

Why would teams continue to sign a player with an increasing reputation for unreliability? The answer may lie in Creeden’s hitting statistics: Simply put, he mashed from the left side almost everywhere he went.53 After his banishment from Boston, he hit .323 in 63 games for Utica in 1943. The following year he hit .305 in a season split between Seattle of the Double-A Pacific Coast League and Little Rock of the Class A-1 Southern Association – a season that ended with Creeden making an agreement to play for an independent team in Massachusetts and then not showing up.54

Back in the Southern Association for 1945, Creeden was sold in mid-season from Little Rock to Atlanta. Final statistics published after he jumped the Atlanta team reported his average as .362, placing him among the league leaders.55 He apparently sat out the 1946 season, dividing the year between coaching at Morgan and working as associate headmaster, athletic director, and coach at the newly founded Burritt Preparatory School.56

Back in the pros in 1947, his .393 average in 113 games with Port Chester led the Class B Colonial League in hitting.57 As previously mentioned, he excelled at the plate for Florence and St. Hyacinthe in 1948; in his early-season stint with the traveling House of David team, he hit nine home runs in a month.58 By 1949 he had descended to the semipro level with the Galt (Ontario) Terriers of the Intercounty Baseball League, where he also participated as a hitting coach in a three-day school for boys.59

Creeden’s final season, with the Superior Knights in 1950, saw him thump semipro pitching to the tune of .391 in 120 at-bats, ranking him second in the league.60 News accounts of his time with the Knights make no mention of his going absent during the season. But on October 24, Creeden’s boss at a local car dealership, who had heard rumors about his behavior, called him in and fired him. Creeden abruptly left town, shortly before a county sheriff arrived to serve a warrant for his arrest.61 He was arrested in Denver, Colorado, and returned to Superior, where he pleaded guilty.62

To piece together the 15 years that remained of Creeden’s life after his parole, it helps to start with two documents issued after his death.

The first is his state of California death certificate, which identified him as “Cornelius Stephen Creeden aka Lee Burton.”63 Creeden/Burton was listed as a self-employed musician, in that business for 30 years, and as a resident of Santa Ana in Orange County near Anaheim. He was also married to the former Joanne Daigle, who took the name Joanne Burton.64

The second document is an undated letter written by Joanne Burton, apparently in response to an inquiry about Creeden’s name change from former Hall of Fame historian and SABR founding member Cliff Kachline. The response is transcribed here in full. Whether Mrs. Burton was glossing over what she knew to protect her late husband, or had never actually pushed her husband for a proper explanation, is for the reader to guess:65

“Dear Mr. Kachline, I’m afraid I can’t give you a very sensible reason why Lee changed his name. I know that he never liked the name Cornelius, and I would guess that ‘Connie’ sounded too sissy to suit him. He changed his name when he began working steadily as a professional musician. I’m sure he felt that ‘Lee Burton’ would be simpler and easier for people to remember. Sorry I can’t be of more help. Yours truly, Joanne Burton.”

A reasonable observer would imagine that a man of Connie Creeden’s heft could have easily put the kibosh on any nickname he found “too sissy.” The same observer might also guess that a well-traveled athlete would want to trade on his name recognition in his subsequent career, because the fans who remembered his home run hitting might be inclined to come watch him play the organ. Neither of these things happened in Creeden’s case.

Identifying where Creeden was between 1954 and 1969 is also difficult. A scattering of newspaper advertisements and stories from that period promote appearances by a keyboardist named Lee Burton – but none, of course, draw a straight line between Burton and Connie Creeden.

In November 1954, shortly after Creeden’s parole from the state penitentiary at Lincoln, Nebraska, ads began to appear in Omaha newspapers for an organist named Lee Burton playing at a roller rink.66 The ads continued until May 1955. The roller rink continued to advertise after that, but Burton’s name disappeared from its promotions, and no organist or pianist named Lee Burton was subsequently mentioned in Omaha newspapers.67

An organist named Lee Burton also appeared in Kansas City and Chillicothe, Ohio, in 1958; Albuquerque in 1960; Alamogordo, New Mexico, in 1961; Phoenix in 1962; and in Escondido, California, near San Diego, in 1966.68 One of the ads from Phoenix included a head shot of Burton; he passably resembled an older Creeden, though the photo is too small to be certain.69 The Escondido appearance was likely to have been Creeden, because another clue places him in that area around the same time. Joanne Burton’s mother, Rose Daigle, died in Nebraska in January 1966. Her newspaper obituary listed her daughter, Joanne, and husband, Lee Burton, living in San Diego.70

The Burtons had been living in California for about five years and Orange County for about one and a half when a coronary thrombosis ended Creeden’s life on the evening of November 30, 1969. Stricken elsewhere, he was declared dead on arrival at a hospital in Santa Ana. He was buried on December 4 in Good Shepherd Cemetery in the coastal community of Huntington Beach, California.71

Whether by happenstance or design, Creeden’s travels ended almost as far from Danvers, Massachusetts, as it’s possible to go while still being in the continental United States. He is buried under a military-issue gravestone, a remnant of his service in 1940-41, bearing the name Cornelius S. Creeden.72 Still, his alternate identity outlives him in at least one regard. The website for Good Shepherd Cemetery has no listing for Cornelius Creeden; to find his grave, one must search the site for Lee Burton.73

Acknowledgments

This story was reviewed by Rory Costello and Rick Zucker and fact-checked by Dana Berry. The author thanks the Giamatti Research Center at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum; the Peabody Institute Library of Danvers, Massachusetts; and Brian Brownfield of the athletics department at St. Mary’s College of California for assistance with research.

Sources

In addition to the sources credited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org for background information on players, teams, and seasons. He also consulted numerous box scores and game stories for games featuring Connie Creeden.

Notes

1 “Moose Skipped Out Just Ahead of Law,” Superior (Nebraska) Express, October 26, 1950: 1; “Creeden Bound Over to District Court,” Superior Express, November 2, 1950: 1. The formal charge against Creeden was sodomy, according to several legal notices and news reports related to his parole, including a legal notice published in the Nelson Gazette (Ruskin, Nebraska), October 7, 1954: 3.

2 “Moose Skipped Out Just Ahead of Law.”

3 “Creeden Sentenced to 10 Years in Pen,” Superior Express, December 7, 1950: 1; Associated Press, “Pardon Given Detroit Man,” Omaha (Nebraska) World-Herald, October 21, 1954: 8.

4 Information on the Lee Burton name and Creeden’s post-baseball career is based on his death certificate, which is cited and extensively discussed in this article.

5 At the time this story was written in July 2023, Creeden was the most recent of four major-leaguers to be born in Danvers. The other three were Dan “Coke” Woodman (born 1893; played 1914-15); Ed Caskin (born 1851, played 1879-1886); and Thorny Hawkes (born 1852; played 1879 and 1884.)

6 Familysearch.org main page for Cornelius Stephen Creeden and 1910 and 1930 US Census listings for John Creeden and family, both accessed June 2023.

7 “Tapleyville Tips,” Danvers (Massachusetts) Herald, November 25, 1931: 14.

8 “Danvers Boy Near Death in Hunting Trip Mishap,” Boston Globe, January 4, 1932: 13.

9 “Tapleyville Tips,” Danvers Herald, October 20, 1932: 8; “Tapleyville Tips,” Danvers Herald, November 10, 1932: 8.

10 Wally Provost, “Superior Issues Challenge to PNL,” Lincoln (Nebraska) State Journal, May 14, 1950: 5B. This is one of several news articles from Nebraska in 1950 that describe Creeden as Canadian, presumably a misunderstanding based on the fact that Creeden played the previous season for the Galt Terriers of Canada’s Intercounty Baseball League. Creeden was also listed at 210 pounds on his Sporting News player contract card, 220 pounds by the Boston Globe in 1943 (Roger Birtwell, “Creeden Refuses to Go to Minors; Is Suspended,” Boston Globe, May 14, 1943: 29), and 240 pounds by the Fremont (Nebraska) Tribune on August 1, 1950.

11 “Connie Creedon [sic] to Play Organ at Orpheum,” Danvers Herald, January 18, 1940: 7.

12 Hobe Hays, “Sports Haze…,” McCook (Nebraska) Daily Gazette, June 14, 1950: 7.

13 “Tapleyville Bright Spot of Local 4th Celebration,” Danvers Herald, June 30, 1932: 1.

14 Harvey L. Southward, “Itemizing the Sports,” Lynn (Massachusetts) Daily Item, August 4, 1941: 10.

15 Numerous, including “Outfielder to Coach,” Detroit Times, October 20, 1945: 24C, and “Morgan, McCallie’s Foe Friday, is Undefeated in Three Tussles,” Chattanooga (Tennessee) Times, October 18, 1945: 13.

16 “Boys’ Prep School to Open on Plateau,” Knoxville (Tennessee) News-Sentinel, July 26, 1946: 21.

17 “Con Creedon Named Coach,” Nashville (Tennessee) Banner, June 28, 1946: 29.

18 In his book Terrier Town: Summer of ‘49 (Waterloo, Ontario, Canada: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2003), author David Menary wrote that some in Galt, Ontario, suspected Creeden of being a pedophile during his season playing for the Galt Terriers in 1949, and that the player “left town in disgrace.” Menary’s book (which misspells Creeden’s name) does not indicate that formal charges were filed in Galt.

19 In “Con Creeden Named Coach,” he is “the former star athlete at St. Mary’s College.” He is a graduate of St. Mary’s in “Burritt College Leased; Boys School Formed,” Nashville (Tennessee) Banner, June 27, 1946: 8. He is an “ex-B.C. gridder” in “In Different Togs” (photo and caption), Portland (Maine) Evening Express, September 12, 1947: 23, and a “former Boston College luminary” in Bud Cornish, “Sagamore Coach Out; To Form New Eleven,” Portland Evening Express, October 2, 1946: 1.

20 2022 Boston College football media guide (Boston College, Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts): 73. The author also searched Boston College’s online student newspaper archive in June 2023 without result, with the idea that Creeden might have been mentioned in game coverage. Searches were conducted for multiple variations on Creeden’s name, using Cornelius, Connie, and Con for a first name and Creeden and Creedon for a last name. An unsuccessful search was also run using the terms Creeden/Creedon and Danvers, on the theory that the BC paper would be likely to mention a player’s more-or-less-local origins.

21 Email correspondence between the author and Brian Brownfield, assistant athletics director for communications, St. Mary’s College of California, June and July 2023.

22 Searches conducted in June 2023; transcription of US Army enlistment record for Cornelius S. Creeden, accessed via Familysearch.org in June 2023. Patrick “Pat” Creeden was also a Massachusetts native (though not a direct relative of Connie Creeden) and also played major-league baseball, appearing in five games with the Red Sox in 1931. “’Paddy’ Creeden Seeks Representative Post,” Boston Globe, August 4, 1934: 3.

23 “New Enthusiasm Evident in Tapleyville Baseball Team,” Danvers Herald, April 18, 1935: 6.

24 “Chief Red Sox Scout Puts Stamp of Approval on Creedon [sic] as a Future Star,” Danvers Herald, December 31, 1936: 6. This article reprints an interview, in highly florid language, granted by Duffy to the Boston Traveler newspaper.

25 “New Gardener Joins Red Sox,” Mansfield (Ohio) News-Journal, May 26, 1937: 12. As of the time this story was written in June 2023, Creeden’s 1937 experience with the Mansfield team was not included on his Baseball-Reference page.

26 “New England Semi-Pro Title Claimants,” Portsmouth (New Hampshire) Herald, September 30, 1937: 6. Creeden’s Sporting News contract card indicates that he signed in August 1937 with a Boston Bees farm team in Beaver Falls, Pennsylvania. A Newspapers.com search in June 2023 found no mentions of Creeden playing there.

27 “Larkin Selects All-Cape Team,” Boston Globe, September 6, 1938: 20; Fred Jones, “Sportcity,” Portsmouth Herald, September 30, 1939: 5.

28 “Fans Lament Present Status of Town Baseball Teams,” Danvers Herald, June 8, 1939: 3.

29 A few citations from this period: “City Team and Plymouth Face Off Here Tomorrow Afternoon,” Portsmouth Herald, October 7, 1939: 5;Tom Shehan, “The Sporting Way,” Danvers Herald, September 12, 1940: 6; Tom Shehan, “The Sporting Way,” Danvers Herald, September 25, 1941: 6.

30 As of June 2023, Baseball-Reference’s record for Creeden had him hitting .238 in 15 games with Sydney Mines in 1939, but had no listing for his 1940 minor-league appearances. His presence in Wilmington and Saginaw is confirmed in “Blue Rocks Battle Charlotte Club to 1-1 Deadlock,” Wilmington (Delaware) Morning News, April 8, 1940: 17, and Dick Renard, “Calling the Turn,” Wilmington Journal, May 14, 1940: 30.

31 Transcription of US Army enlistment record for Cornelius S. Creeden, cited above.

32 Jack Cuddy (United Press), “Ball-Playing ‘Detective’ Now Haunts Gomez with Hub Braves,” Portland (Maine) Evening Express, April 29, 1943: 17; United Press, “Sport Spurts,” Opelousas (Louisiana) Daily World, July 18, 1945: 10. The latter story has Creeden’s neck injury occurring while playing for St. Mary’s College; the former story does not specify where or when it occurred.

33 The Bradford team signed Creeden on the recommendation of manager Jack Burns, a former big-league first baseman and Cambridge, Massachusetts, native. Roger Birtwell, “Creeden Hits ‘Em Far and Wide for Braves,” Boston Globe, March 27, 1943: 4.

34 According to Baseball-Reference’s page on the 1942 PONY League (accessed June 2023), the average age for a league pitcher was 20.1 years, while the average age for batters was 21.3 years.

35 “Bees Sell Four Star Performers to Class A,” Bradford (Pennsylvania) Yankee Doodler, September 17, 1942: 1. As of June 2023, Baseball-Reference credited Creeden with a slightly lower average – .349 – and did not list his number of RBIs. Other news sources found in the research for this article pegged his RBI total at 118 and his average at .350.

36 “Welcome Dinner for Burns Bees Opens 1942 Campaign,” Bradford (Pennsylvania) Evening Star and Daily Record, April 29, 1942: 8; “Rickey Promises Oilers Help at Opening Banquet,” Olean (New York) Times-Herald, April 30, 1942: 5.

37 “Spring Training Baseball Comes to Wallingford,” Connecticuthistory.org, March 22, 2020 (https://connecticuthistory.org/spring-training-baseball-comes-to-wallingford/).

38 Cuddy, “Ball-Playing ‘Detective’ Now Haunts Gomez with Hub Braves.”

39 Roger Birtwell, “Tattered Braves Lose Fernandez,” Boston Globe, March 23, 1943: 26. As a rookie in 1942, Fernandez had played a majority of his games at third base, but was penciled in as an outfielder in 1943.

40 Roger Birtwell, “Workman In Role of ‘Mystery Man,’” Boston Globe, March 24, 1943: 21; Birtwell, “Creeden Hits ‘Em Far and Wide for Braves.”

41 “Training Camp Briefs,” Columbian (Vancouver, Washington), March 29, 1943: 5.

42 Roger Birtwell, “Braves Nick Phils, 3-1, Lose 2nd in 12th, 6 to 5,” Boston Globe, May 3, 1943: 7.

43 Roger Birtwell, “Creeden Refuses to Go to Minors; Is Suspended,” Boston Globe, May 14, 1943: 29.

44 Associated Press, “Utica Braves Sign Outfielder Creedon [sic,” Hartford Courant, May 19, 1943: 14; International News Service, “Hollywood Purchases Creeden from Utica,” El Paso (Texas) Herald-Post, July 24, 1943: 6.

45 Creeden’s Sporting News contract card can be viewed online. The Sporting News Player Contract Card, https://digital.la84.org/digital/collection/p17103coll3/id/45733/rec/1 (accessed August 25, 2023).

46 Harvey L. Southward, “Itemizing the Sports,” Lynn Daily Item, August 31, 1945: 16.

47 “Connie Creeden, Now in Class B Loop, Is Still Setting Records,” Danvers Herald, September 18, 1947: 8.

48 Associated Press, “Criminal Action Could Be Result,” and “Creeden Jumps Florence Club,” both Charlotte (North Carolina) News, June 2, 1948: 6B.

49 “Police Chief Says: Ball Game ‘Fixers” in 3 N.C. Cities,” Atlanta Constitution, June 3, 1948: 24.

50 Furman Bisher, “Weingarten Returns to Florence,” Charlotte News, June 4, 1948: 6B.

51 A story that appeared after the end of the season mentioned the suspicious timing of Creeden’s departure but noted that nothing was ever proven. “The Fix Leaked and Death Came,” Charlotte News, September 22, 1948: 19C.

52 Wirt Gammon, “Just Between Us Fans,” Chattanooga Times, October 26, 1945: 17.

53 One notable exception was Hollywood of the Pacific Coast League in 1943, where he hit just .229 in 23 games.

54 Harvey L. Southward, “Rhode Island Club Out to Beat Jack Fallon,” Lynn Daily Item, July 27, 1944.

55 Joe Livingston, “341 of Crackers’ Total Runs Sent Across by Three Batters,” Atlanta Journal, September 16, 1945: 20; Ed Danforth, “An Ear to the Ground,” Atlanta Journal, August 29, 1945: 16.

56 Billy Thompson, “Litton Loses Billy Benz for Remainder of Season,” Nashville Banner, February 12, 1946: 11; “Con Creedon [sic] Named Coach,” Nashville Banner, June 28, 1946: 29. A Newspapers.com search conducted in August 2023 for all available newspapers in 1946, for the names Connie Creeden and Connie Creedon, turned up no in-season reports of Creeden appearing in pro baseball.

57 Baseball-Reference credits Creeden with a .394 average in 1947. The .393 figure is taken from a season-ending roundup: “Korponay’s 11 Triples Cop Title,” Poughkeepsie (New York) New Yorker, September 12, 1947: 16.

58 J. Suter Kegg, “Tapping on the Sports Keg,” Cumberland (Maryland) Sunday Times, May 9, 1948: 29.

59 Canadian Press, “45 Youths Attend Galt Ball School,” Windsor (Ontario) Star, August 9, 1949: 3.

60 “Two Bear Batters Were in Top Ten of NIL Sluggers,” Holdrege (Nebraska) Daily Citizen, September 2, 1950: 4. Creeden also ranked among league leaders in doubles, triples, and RBIs.

61 “Moose Skipped Out Just Ahead of Law.”

62 “Creeden Bound Over to District Court.”

63 Creeden/Burton’s death certificate is included in his clipping file at the Giamatti Research Center at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

64 Transcription of Social Security document for Joanne Beverly Daigle (Burton), accessed via Familysearch.org in June 2023. The record indicates that Joanne Beverly Burton filed a Social Security-related application in September 1959, which could mean that the couple was married that year.

65 Joanne Burton cannot speak to the question herself, as she died in 1986, according to California death records accessed via Familysearch.org in June 2023. Her letter to Kachline is included in Creeden’s clipping file at the Giamatti Research Center.

66 Omaha is roughly an hour’s highway drive from Lincoln.

67 In June 2023, the author ran a Newspapers.com search for the name “Lee Burton” in Omaha, Nebraska, between 1945 and 1975. The only reference to a Lee Burton prior to November 1954 was a mention of the owner of a local airstrip in 1952. The Lee Burton organ ads for Crosstown Roller Rink ran from November 9, 1954, to May 22, 1955. There were no subsequent references to a musician named Lee Burton in Omaha newspapers; from 1955 through 1975, the name only occurred in other contexts, such as an unrelated person’s middle and last names. (Burton/Creeden was mentioned in the Omaha Evening World-Herald in the death notice of his mother-in-law in January 1966, which is cited below at endnote 70.)

68 Kansas City and Chillicothe: Advertisement for Beardmore Furniture Company, Chillicothe (Ohio) Constitution-Tribune, November 24, 1958: 3; Albuquerque: Advertisement for Barber’s Super Market, Albuquerque Journal, September 30, 1960: 50; Alamogordo: “Sierra P-TA Hears Dr. Wivel,” Alamogordo (New Mexico) Daily News, February 23, 1961: 2; Phoenix: Advertisement for Palomine Inn, Phoenix (Arizona) Republic, May 26, 1962: 54; Escondido: Eloise Perkins, “North County Nuggets,” Escondido (California) Daily Times-Advocate, December 6, 1966: 8. If any of these listings is least likely to be Creeden/Burton, it’s probably the Alamogordo listing, which is for a private event (a parent-teacher association meeting) rather than in a public setting.

69 Advertisement (headlined “Entertainment Nightly”) for Yucca bar and restaurant, Phoenix (Arizona) Republic, October 13, 1962: 55.

70 “Daigle” (obituary), Omaha Evening World-Herald, January 10, 1966: 28. The obituary also mentions a grandchild. Author David Menary, in Terrier Town (cited above), mentions the Burtons having a son; the author of this article was unable to confirm that.

71 Creeden’s death certificate is the source of all information in this paragraph.

72 Findagrave.com entry for Cornelius Stephen Creeden, accessed June 2023. His wife, Joanne, is buried in another section of the same cemetery.

73 Web search on the Diocese of Orange County Catholic Cemeteries site, conducted June 2023. A guess: Creeden’s burial site was purchased under the name Lee Burton, and the cemetery records reflect that name rather than the name on his gravestone.

Full Name

Cornelius Stephen Creeden

Born

July 21, 1915 at Danvers, MA (USA)

Died

November 30, 1969 at Santa Ana, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.