Max West

A bright future appeared to lie ahead for Boston Braves outfielder Max West after he became a major-league regular in 1938 at the age of 21 and was the team’s top offensive performer a year later. Following a memorable appearance in the 1940 All-Star Game, when he hit a home run to win the contest, it appeared that the young slugging outfielder might be able to lift the Braves out of the second division of the National League. But injuries and constant position changes prevented him from sustaining the high level of play he experienced during his first few major league seasons. Any chance of a comeback ended when he lost three years of playing time serving in the armed forces during World War II. Not all was lost, though, as West became one of the most celebrated home run hitters in the Pacific Coast League. In fact, he nearly became the league’s all-time home run king.

A bright future appeared to lie ahead for Boston Braves outfielder Max West after he became a major-league regular in 1938 at the age of 21 and was the team’s top offensive performer a year later. Following a memorable appearance in the 1940 All-Star Game, when he hit a home run to win the contest, it appeared that the young slugging outfielder might be able to lift the Braves out of the second division of the National League. But injuries and constant position changes prevented him from sustaining the high level of play he experienced during his first few major league seasons. Any chance of a comeback ended when he lost three years of playing time serving in the armed forces during World War II. Not all was lost, though, as West became one of the most celebrated home run hitters in the Pacific Coast League. In fact, he nearly became the league’s all-time home run king.

Max Edward West was born November 28, 1916, in Dexter, Missouri, a town located about 170 miles south of St. Louis, placed just north of Arkansas and just west of Kentucky. He was the first of two children born to Benjamin and Minnie (née Stewart) West. His sister, Mary Louise, arrived in 1923. Ben worked in the oil industry in Dexter, but before Max turned four Ben moved the family to Alhambra, California, a suburb of Los Angeles, where he later worked in sales at a car dealership. As a student at Alhambra High School, Max received attention as a multi-sport athlete, playing baseball, basketball, and football. Ben had played semi-pro baseball, and he recognized that Max had a chance to make a career in baseball, so he convinced his son to give up football to avoid injury.1

Los Angeles is also located less than nine miles from Glendale, California, which, coincidentally, is where Brooklyn Dodgers manager Casey Stengel made his offseason home. Stengel went to Los Angeles in the fall of 1934 to scout at a local tournament, and the young left-handed batter (but right-handed thrower) caught his attention. Stengel wanted to sign West for the Dodgers, but Earl McNeely of the Sacramento Solons got to West first. Before Stengel even laid eyes on him, McNeely had already signed West away from a scholarship offer from the University of Southern California to instead play for his Pacific Coast League club. Later in the year, Stengel and McNeely found each other riding the same train back east. Stengel still lamented over losing out on the young player.2

West was only eighteen when the 1935 season began, so he was expected to be farmed out to a lower minor league team. Instead, he remained on the Sacramento roster in Class AA all year. (West joined the select company of players never to play below the AA level.) One of West’s earliest appearances for Sacramento was in a March exhibition game against the Tokyo Giants, who were touring America. West went 0-for-4 in a loss to Eiji Sawamura, the pitcher who would one day be the namesake of the annual award for the top pitcher in Japan.3

Following the season, McNeely left his role as president-manager of the Solons to take a coaching position with the Washington Senators. With the Sacramento team in financial trouble, McNeely sold off most of the team’s contracts. Without any takers immediately stepping up to buy the Solons, the Anglo-California Bank took possession of the remaining contracts. West was one of the players who became bank property until the financial institution sold his contract to the league-rival Mission Reds in San Francisco.

Over his two seasons with the Missions, West filled out his 6-foot-1 frame. He eventually weighed over 180 pounds, and with that added weight came more power. His 16 home runs and 61 extra-base hits led the Reds in 1937, and he batted over .300 in both seasons. He also got a measure of payback against the Tokyo Giants in March 1936 when he scored the only run in the Reds’ 1–0 exhibition victory.4

The Boston Bees, as the team had come to be known in 1936, purchased West’s contract from the Missions in September 1937. Three years after commiserating over his loss of the young Californian, Stengel finally got his man when he was named the Bees manager in October. West was initially taken aback when he was informed of the deal while on the road in Los Angeles. “I was in the clubhouse at Wrigley Field. … I cried. It was like I was going to Siberia!”5

After batting .400 during the winter for the White Kings in the popular California Winter League,6 West headed to spring training in Bradenton, Florida, where he was already being proclaimed a top prospect for the Bees.7 From the start of camp, manager Stengel took West under his wing. West rewarded Stengel’s faith by batting .290 with 25 hits in his first 22 exhibition games,8 and his batting prowess was called the single outstanding development in camp.9 But there was a question of where West would play. He was often aloof in the outfield, and his fielding wasn’t much better at first base. West won the first-base position over incumbent Elbie Fletcher when the season started, but it became apparent after only seven games that Fletcher’s glove was needed, and West moved to left field.

During the Bees game on May 28, West suffered a concussion when he ran into a fence chasing a fly ball, and he missed the next eight games as a result. West was only twenty-one when the 1938 season began, but he had already endured his share of injuries. While playing in the minor leagues he had fouled balls off his ankle, knocked himself out running into a catcher, sprained his leg with an awkward slide, and suffered other miscellaneous ailments. No one could question West’s hustle, and coaches appreciated his eagerness to learn and make himself a better player, but his knack for getting injured would plague him throughout his career. This would not be the last time he lost a fight with an outfield wall. Stengel would later say of West, “He’ll kill somebody someday. I hope it ain’t himself…”10

Bees fans were mildly disappointed with West’s 1938 rookie campaign after the lead-up to it. Still, West provided one of Boston’s season highlights when on July 9 he and teammates Tony Cuccinello and Fletcher hit three consecutive home runs in an inning, against Carl Hubbell no less. But Boston rooters hoped for more than a .234 average and 10 home runs from the rookie, and West could not help the Bees climb out of the second division. Stengel pointed out that many of West’s fly outs to the deep right garden at Braves Field would have resulted in home runs in other parks.11 Earlier in the season, however, Stengel admitted that West may not have been ready for the majors yet.12 But the Bees skipper stuck with his man, and it paid off in 1939 when West had the breakout year everyone was waiting for.

West led the 1939 Bees in several traditional statistics, including 19 home runs, 26 doubles, 51 walks, and 82 RBIs. More modern statistics show just how good a season he had. His .861 OPS was ninth in the NL, and his 137 adjusted OPS+ ranked sixth. He finished sixth in the league in home runs, hitting at least one in every NL park.13 Only two of his 19 home runs were hit at his home ballpark, and he twice hit homers in both games of a doubleheader. If there was a blemish on West’s season, it may have been his 1-for-10 outing on June 27 during a 23-inning marathon game against Brooklyn. His bat earned him MVP consideration after the season, but West continued struggling in the field. Stengel rotated him between all three outfield spots to find where he fit best – or maybe where he would do the least damage. Stengel was once quoted as saying that West should play the outfield with an umbrella in one hand. “It’s the only thing that’ll save him from catching flies with his head.”14

The Bees were constantly in cost-cutting mode, and practically every other NL team tried to purchase West following the 1939 season. However, Stengel and Boston president Bob Quinn saw him as a potential building block towards constructing a winning team and turned down offers that reportedly reached as much as $55,000 and four players.15 West was too busy in the offseason to worry about trade rumors. He wed Virginia Farmer on November 18. The couple would have a son, Ralph (named for fellow Alhambra native and friend Ralph Kiner), and a daughter, Cindy.16 Then, in March, he was selected to play in an all-star game being held to benefit the citizens of Finland after the Soviet Union invaded the country.

His numbers through July 1940 weren’t on par with his 1939 season, but when it came time to build the National League All-Star roster, West was selected as Boston’s sole player representative, though Stengel also joined as a coach.17 Days before the July 9 game, NL manager Bill McKechnie announced Giants star Mel Ott as his probable starter in right field. Shortly before the game began, however, McKechnie declared that West, the youngest player on the squad, would instead get the start in right field and bat third in the lineup, leaving Ott to come in later and play the sun field if necessary.18 After the American League began the game with a scoreless top of the first inning, NL leadoff batters Arky Vaughan and Billy Herman hit back-to-back singles off AL starter Red Ruffing. West came up next and clubbed a low fastball 360 feet into the right-field pavilion at St. Louis’ Sportsman’s Park. Before Ruffing even recorded an out, the game was lost, as the AL became the first shutout victim in All-Star history.

West was hailed as the game’s hero in the next day’s newspapers, though his All-Star experience had been short-lived. He marched back out to his position in right field at the start of the second inning; then, with one out Luke Appling hit a fly ball in his direction. West chased the ball and made a running leap for it, but he leaped right into the outfield wall and fell to the ground. Stengel had to be mortified as he watched his star player collapse, but West was helped up and walked off the field with only a bruised hip.19

West exceeded his 1940 All-Star season in 1941 when he hit .277 with 12 home runs, and he finished fifth in the league with 16 home runs in 1942. But West could not match the success of his 1939 season. Other NL teams continued approaching Boston about obtaining West, but the club, now known as the Braves once again, wouldn’t budge. Stengel later explained, “I always passed up those chances…because I’ve felt all along that a kid with West’s moxie can’t miss becoming an established major leaguer.”20

Boston finished in seventh place from 1939 to 1942 (with only the lowly Phillies keeping them from finishing last), and West grew discontented as he saw the cash-strapped team deal teammates to contenders. Boston writers questioned Stengel’s sticking with his “cousin” West, but Stengel said if anything, he had done more harm than good to West by moving him around the field and the lineup. “I have given him about the rawest deal I’ve handed any player on our club. I’ve tossed him around from one position to another with reckless abandon.”21

The low point of West’s time with the Braves came during a doubleheader against Philadelphia on September 7, 1941, when he had what the Boston Globe considered a bid for the “Prize Boner of the Year.”22 After a groundout in the fourth inning of the second game, West slowly meandered back to the dugout as play resumed. As he walked by, a pitch got past catcher Mickey Livingston and rolled towards him. West casually picked up the ball and tossed it to Livingston. Unfortunately, he didn’t realize that his teammate Frank Demaree was trying to score from third on the play. Livingston received the toss and relayed it to pitcher Tommy Hughes, who was covering home and waiting to tag out Demaree. West was understandably still stewing about the play an inning later when he went to the water cooler. As he was getting a sip of water, a foul ball off the bat of teammate Paul Waner struck him in the mouth, breaking several teeth and putting him out of action for two weeks. In fairness, West had a triple and a home run and scored three runs in the first game that day.

West was just twenty-six and still in his prime years when the 1943 season began. With a new season came an opportunity to rebound and maybe return to All-Star status. Those plans had to be put on hold; in March 1943, West was inducted into the United States Army Air Corps. He was a baseball celebrity when he entered the military, and as such, he was assigned to the Sixth Ferrying Command at Long Beach, California, along with other major leaguers. West’s teammates with the Ferrying Command included his All-Star teammate Harry Danning, and fellow Brave Nan Fernandez. The team’s manager, coincidentally, was West’s former All-Star Game victim Ruffing.

For the next three years West played ball in military leagues and various all-star and fundraising games at locations throughout California and the Pacific Theater. West’s time in the service, however, was anything but a vacation. After training, he was sent to the Western Pacific Islands region, where he helped during takeoffs and landings as a ground crew support member. The crew also responded when the planes crashed, and memories of horrific scenes would plague him for the rest of his life. “One time…we pulled out this pilot…he had just flown all of us to Saipan for a ballgame a few days before…He was burned pretty badly, and all I saw were his eyes…he looked right at me, his lips kind of smiled and he just died.”23

West was happy to play games to boost the morale of other servicemen, but the baseball schedule could be tiresome when balancing it out with the work schedule. “…We had a job to do as flight/grounds crewmen and…they’d tell us about nine o’clock at night, ‘You’re leaving at six o’clock in the morning for wherever.’”24 West lost three years of his prime playing time serving during WWII, but he said he wouldn’t have changed a thing. “Some people would think I have regrets about changing my baseball uniform for one from Uncle Sam, but I do not. I do not have any regrets about doing that whatsoever!”25 In an interview later, West proclaimed he was within eyesight of the Enola Gay as the plane loaded the “Little Boy” atomic bomb in Saipan.26 With the massive number of troops and the amount of activity on the island at the time, that is not out of reason.

Though he played for the popular Rosabell Plumbers semi-pro team back home in California during the winter of 1946 after being discharged, West wasn’t back to full playing shape by the start of Braves camp. He was set back further when he missed time in March following the death of his father. After playing a single game for Boston, he was traded to the Reds for pitcher Jim Konstanty. The Reds, led by West’s former All-Star manager McKechnie, weren’t sure that he would solve their issues in the outfield,27 but they hoped he could provide left-handed power that they were sorely lacking.

It was difficult enough for West to play for Cincinnati while adjusting back to civilian life, but he was also plagued by injuries, including a back infection that temporarily put him in a back brace. He was limited to 72 games for the Reds and hit only five home runs. One of his home runs, hit in the first game of a doubleheader on August 11, was sandwiched between home runs by Grady Hatton and Ray Mueller, making West the first NL player to twice be part of back-to-back-to-back home run successions. Earlier in the season West had found himself in the middle of another interesting moment, when on May 9 he slid into home in the bottom of the sixth inning and was called both safe and out by two different umpires. (He was ultimately ruled safe.)

During his one season in Cincinnati, West never saw eye to eye with team president Warren Giles. West requested a salary increase after the season, and he refused to have surgery done on his back as the team requested. Giles was happy to jettison West off to the San Diego Padres of the Pacific Coast League in February.28 Giles may have considered the transaction punishment, but West was rejuvenated by the move back to his home state. He recovered from his back problems and had a season not seen in San Diego since Ted Williams wore a Padres jersey. His 120 walks and 124 RBIs set new team marks, and his 43 home runs broke the Padres record previously held by Williams.29 His home run and RBI totals both topped the PCL.

After his colossal 1947 season, it was a safe bet that West would be taken in that year’s major league draft of minor league players. Not that West needed to be evaluated, but scout and former major leaguer Babe Herman, a teammate of West’s in the California Winter League, convinced Pittsburgh to take a chance on him.30 The Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph interviewed West about returning to the major leagues, and he stated that both his confidence and health had returned, and he was excited to play regularly for the Pirates.31 During an interview conducted by Bill Swank and Bill Capps in 1995, West gave a more honest opinion of going to Pittsburgh. “I had to take a cut to go to Pittsburgh, but I needed it for my pension. Most of the guys who played out here wanted to stay…We’ve got the good climate [in California].”32 His batting average reached as high as .323 on May 20; from there it plummeted. He finished the year with only 26 hits in 146 at-bats for a .178 average, though eight of his hits were home runs. On April 25, during one of his few starts, he tied a modern-day NL record by drawing five consecutive walks.33 Otherwise, West wound down his major-league career without making much of an impact for the fourth-place Pirates.

In his seven major-league seasons, West hit for a .254 batting average with 77 home runs despite missing three seasons while serving in the United States Armed Forces. And he will always have a place on the list of the game’s most memorable All-Star appearances. It was in the Pacific Coast League, however, where West made a lasting mark in baseball. West returned to San Diego in 1949 and picked up where he had left off two seasons prior. While West was away in Pittsburgh for one year, Jack Graham hit 48 home runs to break West’s year-old team record. West regained his spot in the Padres record books in 1949 when he clubbed 48 homers to tie the new mark. He also led the PCL in home runs, RBIs, and runs scored, and he provided a veteran presence on a team filled with Indians prospects like Minnie Miñoso, Al Rosen, and Luke Easter.

West topped 30 home runs for four consecutive seasons playing for San Diego and then the Los Angeles Angels, who obtained him in March 1951. In Los Angeles, West was teammates with future TV star Chuck Connors. West also had a short-lived acting career, one might say, when he appeared as a background ballplayer in the 1949 biographical movie The Monty Stratton Story.34 While he never achieved the same success as Connors in front of the camera, West did start up a successful sporting goods store in Alhambra with Ralph Kiner. West was also an usher at Kiner’s wedding in October 1951.

When the 1953 season began, West was 36, and the numerous aches and injuries over his career had taken their toll. He was limited to 38 games and had only 13 hits, five of which were home runs. Despite severe knee pain, he returned for the 1954 season. With 218 career PCL home runs, he was within reach of the all-time PCL home run mark of 251 held by Buzz Arlett. West hit 12 home runs, leaving him 21 short of the record, but his playing career ended when he was released after the season. He was inducted into the minor-league San Diego Padres Hall of Fame in 1965.35

Following his retirement, West remained close to the game through his sporting goods business. He supplied sports equipment to several teams and players in the area, and he represented the Rawling Sporting Goods company at various events. The Angels even worked with West to design their uniforms for the 1956 season. West appeared at old-timer’s games over the years, and he often attended events commemorating the glory days of the old Pacific Coast League before the major leagues moved to California. In October 2003, West was diagnosed with brain cancer. He passed away in Sierra Madre, California, on New Year’s Eve, 2003, just a month after turning eighty-seven, and was cremated. He was survived by his two children. His wife, Virginia, had passed away in 1990.

In celebration of its 100th anniversary in 2003, the Pacific Coast League reopened its Hall of Fame.36 The hall went inactive after 1957, and the 2003 election committee was determined to make up for lost time. They faced the arduous task of identifying the greatest of the thousands of players who had passed through the league in the nearly 50 years since the hall closed. Max West was an easy choice to be one of the 21 inductees in the class.

Acknowledgments

This article was reviewed by Gregory H. Wolf and Abigail Miskowiec and checked for accuracy by SABR’s fact-checking team.

Shawn Hennessey assisted with research on Max West’s time playing ball in the military.

Mitch Soivenski helped run data queries for games with three consecutive home runs in an inning.

The National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum provided the player file for Max West.

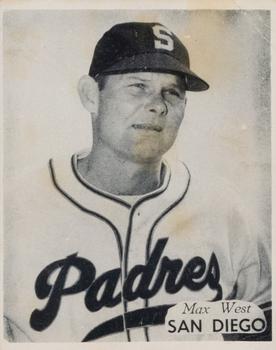

Photo credit: Max West, Trading Card Database.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author relied on Baseball-Reference.com, Ancestry.com, Newspapers.com, and Chevronsanddiamonds.org.

Johnson, Lloyd, ed. The Minor League Register, (Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America, Inc., 1994).

Kaese, Harold. The Boston Braves, (New York: Van Rees Press, 1948).

Sharp, Andrew. “Earl McNeely,” SABR Baseball Biography Project, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/earl-mcneely/, accessed March 1, 2025.

Spalding, John E. Pacific Coast League Stars: One Hundred of the Best, 1903 to 1957, (Manhattan, Kansas: Ag Press, 1994).

Notes

1 Dick Farrington, “Ice Cream Sodas and Pitching ‘Popper’ Inspired Max West, Bee Rookie Socker,” The Sporting News, June 2, 1938: 5.

2 Rudy Hickey, “Max West, Who Helped Brooklyn Tie-up, Is Good Looking Recruit,” Sacramento Bee, March 6, 1935: 16.

3 “Sawamura Turns Back Regulars,” Sacramento Union, March 18, 1935: 7.

4 “Missions Win Game,” Morning Press (Santa Barbara, CA), March 18, 1936: 12.

5 Bill Swanks and Bill Capps interview with Max West for the San Diego History Center, https://sandiegohistory.org/journal/1995/january/west-3/, accessed October 15, 2024.

6 William F. McNeil, The California Winter League: America’s First Integrated Professional Baseball League (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc, 2002), 191.

7 James Bagley, “Stengel Expects to Keep Bees up in Fifth Position,” Springfield (MA) Daily News, February 23, 1938: 20.

8 Robert Webb, “Says Red Sox and Bees Look Like Fifth-Place Ball Clubs,” Springfield Daily News, April 13, 1938: 20.

9 Gerry Moore, “Where to Use West Is Worrying Stengel Now,” Boston Globe, April 5, 1938: 11.

10 John Lardner, “Meet Casey’s Killers,” Boston Globe, March 14, 1939: 6.

11 Braves Field was temporarily renamed while the team played as the Bees.

12 Bill King, “Cooney Helps Bees Greatly,” Berkshire Evening Eagle (Berkshire, MA), May 12, 1938: 17.

13 Hank Lieber was the other player to accomplish the feat in the NL that year.

14 “Deal for West by Bees Made Coast Guffaw,” Springfield Union, August 22, 1939: 16.

15 George Kirksey, “Boston Outfit Turns down 100Gs for Max West,” Daily News (Los Angeles, CA), December 7, 1939: 17.

16 Jeane Hoffman, “Max West’s Adopted Son Ralph Has Definite Slugging Heritage,” Los Angeles Times, April 15, 1953: 75.

17 Bees shortstop Eddie Miller was added after Bill Jurges dropped out of the game with an injury.

18 “West, Whose Homer Beat A.L., Started on Hunch,” Binghamton Press, July 10, 1940: 16.

19 West returned to action after the All-Star break, but he would miss time later in July recovering from the hip injury.

20 Gerry Moore, “Stengle Disowns Maxie as Cousin,” Boston Globe, March 11, 1942: 20.

21 Moore, “Stengle Disowns.”

22 Melville Webb, “West Makes Prize Bid for Boner of the Year,” Boston Globe, September 8, 1941: 8.

23 Todd Anton, No Greater Love: Life Stories from the Men Who Saved Baseball (Burlington, Massachusetts: Rounder Books, 2007), 140.

24 Anton, 141.

25 Anton, 139.

26 Anton, 142.

27 The Reds went through 12 players trying to fill out their outfield that season.

28 Anton, 147.

29 Al Wolf, “Sportraits,” Los Angeles Times, August 18, 1947: 17.

30 Les Biederman, “Cox, Fletcher in Uneasy Seat After Buc Deal,” The Sporting News, November 19, 1947: 11.

31 Mannie Pineda, “Comeback Chance Thrills Max West,” Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, January 28, 1948: 20.

32 Swanks and Capps

33 Vince Johnson, “Sauer Socks Three Home Runs; First Blow Wins Opener,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, April 26, 1948: 20.

34 Max West’s page on IMDB.com: https://www.imdb.com/name/nm6275603/?ref_=nv_sr_srsg_5_tt_1_nm_7_in_0_q_max%2520west

35 “Five Ex-Greats Inducted into Padre Hall of Fame,” The Sporting News, September 4, 1965: p 36.

36 Sheila Mulrooney Eldred, “Fresno is Deer’s Kind of Town,” Fresno Bee, April 8, 2003: D3.

Full Name

Max Edward West

Born

November 28, 1916 at Dexter, MO (USA)

Died

December 31, 2003 at Sierra Madre, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.