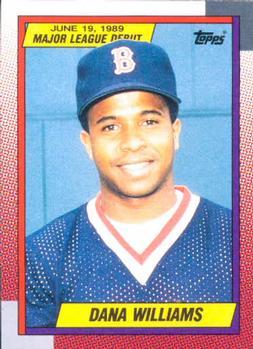

Dana Williams

Though their demanding fans may disagree, the 1980s Red Sox were successful by most measures. While they lost a heartbreaking World Series in 1986 and suffered a League Championship Series sweep two years later, the team enjoyed eight winning seasons against only two losing ones. Their hitters outscored their opponents by an average of 42 runs per season and the ancient turnstiles welcomed more than 19.5 million fans to their beloved Fenway Park. The farm system produced its finest pitcher (Roger Clemens) and third baseman (Wade Boggs). Compared with the fortunes of long-suffering franchises like the Mariners or the Indians, the Red Sox had few gripes.

Though their demanding fans may disagree, the 1980s Red Sox were successful by most measures. While they lost a heartbreaking World Series in 1986 and suffered a League Championship Series sweep two years later, the team enjoyed eight winning seasons against only two losing ones. Their hitters outscored their opponents by an average of 42 runs per season and the ancient turnstiles welcomed more than 19.5 million fans to their beloved Fenway Park. The farm system produced its finest pitcher (Roger Clemens) and third baseman (Wade Boggs). Compared with the fortunes of long-suffering franchises like the Mariners or the Indians, the Red Sox had few gripes.

As the decade began, the outfield was the club’s strength, set in stone by a homegrown trio. Jim Rice had won the MVP in 1978, accumulating 406 total bases, the highest tally since Stan Musial in 1948. Fred Lynn had won both the MVP and the Rookie of the Year awards in 1975 and added the 1979 statistical triple crown with a .333/.423/.637 slash line. Dwight Evans, at 28 the eldest statesman of the group, had picked up three Golden Gloves for his magnificent command of Fenway’s irregularly shaped right field.

But developing players is part art and part science. Boggs supplanted Carney Lansford, who was traded after winning a batting title because his heir apparent was ready. Rich Gedman, while a solid backstop, could not fill the enormous void left by Carlton Fisk, who left for the White Sox. The past-his-prime Tony Pérez, the underpowered Dave Stapleton, and the solid yet unspectacular Bill Buckner manned first base; the franchise was unable to develop any prospects for typically the easiest position to fill in a roster. Red Sox fans were shocked when Lynn, mired in a contract dispute with the club, was traded with Steve Renko to the Angels before the 1981 season. While the Red Sox picked up Joe Rudi, Frank Tanana, and Jim Dorsey, the sudden departure of a young building block was a harbinger of a frustrating, strike-interrupted season. Slugger Tony Armas filled the center-field void in 1983, but the farm system was busy generating other outfielders: Mike Greenwell, Ellis Burks, Todd Benzinger, Kevin Romine, and Dana Williams.

Williams was born on March 20, 1963, in Weirton, West Virginia. His father, Nathaniel, worked in the Weirton Steel Mill but died when Dana was 6 years old. Growing up, Dana and his brothers loved to play the sport: “that’s all I ever did … started at six years old, fell in love with it and never lost the passion. I still have the passion. My dad would tell all of our neighbors to ‘watch my son slide!’”1 His mother, Barbara, remarried and moved the family to Alabama, where Dana grew up. She and her new husband, Joseph Garlington, pursued a religious calling as pastors; in 2019 they led the Covenant Church of Pittsburgh.

In Alabama, Williams continued to turn heads with his athletic abilities. Through the end of the 2019 season, the state had produced 1.7 percent of all men to appear in the major leagues, but its quality surpassed its quantity. Nine Hall of Famers (Hank Aaron, Monte Irvin, Heinie Manush, Willie McCovey, Satchel Paige, Ozzie Smith, Don Sutton, Billy Williams, Early Wynn) hailed from the Yellowhammer State, almost 2.7 percent of the Cooperstown immortals.2

On the high-school diamond, Williams split time between shortstop and the pitching mound. Cincinnati chose him in the 34th round of the 1981 draft, but he opted not to sign and enrolled at Enterprise-Ozark Community College. Baseball celebrated a winter draft to supplement the summer one, and Detroit picked him with the 24th choice in early 1982, but “the money wasn’t right … the true money was in the June draft.”3 Williams returned to school before agreeing to terms with Boston as an amateur free agent on May 17, 1983, for a reported $40,000. Alabama legend Ed Scott, who had discovered Aaron for the Indianapolis Clowns, nudged the Red Sox to offer Williams a contract. This connection to baseball royalty triggered an immense source of joy for Williams: “I’m so proud Ed Scott signed me; he signed Aaron and also Tommie Agee.”

His first professional campaign (1983) saw him split time between Elmira of the short-season Class-A New York-Pennsylvania League and Winston-Salem of the Class-A Carolina League. His bat spoke volumes – he hit .335 in 210 plate appearances – but his defense stuttered: 14 errors in 165 chances at second base, shortstop, and the outfield.

The following year, the Red Sox brass wanted to move Williams to second but “I wasn’t able to do it, so on the last day of spring training they moved me to left field. I ended up leading the league in hits and little by little the errors went down while my hitting improved.” Now patrolling the Winter Haven outfield, he paced the 1984 Florida State League with 167 hits and a .327 batting average, outperforming fellow prospect Burks. In 1985 the organization promoted him to New Britain of the Double-A Eastern League and he responded with a .309 batting average, sixth in the circuit and tops on the team. However, Sam Horn captured the attention of the Red Sox front office, as he projected to be a better power hitter; Burks, while more strikeout-prone, was regarded as a speedier outfielder.

In 1986 there was another promotion, this time to Triple-A Pawtucket. The top farm club is only 46 miles from Boston, but for Williams it may as well have been a world away. Though he appeared in 101 games and garnered 400 plate appearances, his performance was overshadowed by soon-to-be big leaguers Greenwell, Romine, and Jody Reed. The logjam of talent frustrated Williams: “Rice and Evans, they were on their way out; I had no chance. But Burks, Greenwell, Brady (Anderson) … they all jumped over me. (Boston) just didn’t have a place for me.” Power was often cited as the main drawback, but “they put me on the roster I so knew someone wanted me, but they wouldn’t trade me.”

He began 1987 back in Double A but proved he was beyond the competition, producing a .335 average with an .800 OPS in 78 games before returning to Pawtucket. Greenwell was now in Boston and Williams’s .317 average trailed only Benzinger and Horn among farmhands with more than 100 plate appearances. It was a tough year: “I did good; I put the numbers. Why would I quit? I only thought about it when in Triple A behind Greenwell, I hit .270. Greenwell went to the majors and I thought it was my turn, but they sent me to Double A. That was the only time I thought about quitting. But I ended up doing better; I made my second Double-A All-Star team.” Frustrated with Boston’s obsession with round-trippers, he aimed for the fences in 1988, hitting a career-high 10 home runs. But his batting average suffered, dipping to .253.

Meanwhile, the 1989 Red Sox took several steps backward. While their 83-79 record was only six games behind the 1988 pace, the Blue Jays (89-73) and the Orioles (87-75) produced better years. Greenwell delivered solid numbers (123 OPS+ in 145 games) but not as spectacular as his breakthrough 1988 statistics (second in MVP voting, .946 OPS, 160 OPS+). Burks, on the ascend, hit over .300; Evans, on his way out, contributed 20 home runs and 100 RBIs. Boggs turned in his customary numbers (.330 with a .430 OBP) and Clemens garnered 17 wins on a 132 ERA+. Heralded prospect Horn struggled mightily, much to the chagrin of the Red Sox faithful; a washed-up Rice played only 56 games and slashed a career-low .234/.276/.344. In hindsight, the summer was successful because the amateur draft yielded Mo Vaughn, who would win the 1995 MVP Award with the Red Sox, and Jeff Bagwell, who would enter Cooperstown, although as an Astro after Boston flipped him for Larry Andersen in 1990.

After playing 104 games with Pawtucket, Williams was called up to the Red Sox. He entered the June 19 game as a pinch-hitter as Boston trailed the Chicago White Sox 8-2. Manager John McNamara lifted center fielder Randy Kutcher in the ninth inning to call upon his rookie. Like thousands of others before him, Williams grabbed his bat and headed to the plate, dreaming of a hit. While he could not win the game in a single swing, he could ignite a rally by reaching base. Though the cult of OBP was not yet in vogue, players would still take a walk if needed; though not as glorious as making contact, it nevertheless got the job done. Chicago pitcher Donn Pall, working on his third inning, hit Williams with the first pitch. “Bob Stanley told me sometimes pitchers will hit hitters because they don’t want you to get their first hit off them. I don’t know if that was the case or not,” said Williams of the incident. Ninth-place hitter Ed Romero, who would be released on August 5, popped his first offering to right field. Iván Calderón, who played 755 career games in the outfield thanks to a strong arm, dropped the ball, making Williams an easy out at second on the force play; Williams lamented “there was nothing I could do about it” as he headed to the dugout.

As the month progressed, Williams pinch-ran on June 20, played two innings a day later (one at-bat, a strikeout), and enjoyed one plate appearance on June 24. A day later, he found his name on the starting lineup against the Twins. While not a household name, Minnesota starter Allan Anderson spent six years in the majors, enjoying a brief cameo for the 1987 underdog World Series winners (12⅓ innings pitched) and a mediocre 29 games (5-11, 4.96 ERA) for the 1991 last-to-first edition. Between those two campaigns, he shockingly led the league in ERA in 1988 (2.45) and won a career-high 17 games in 1989. Williams, hitting ninth, came to bat in the third inning; he drove an Anderson offering to center field but the ball was caught by John Moses, starting for fan-favorite and eventual batting champion Kirby Puckett’s day off. Though Anderson was not overpowering the hitters (he would not record a strikeout in the game), his mix of pitches kept the Red Sox off-balance and off the scoreboard. Two innings later, with his former minor-league teammate Romine on first, Williams sought the counsel of hitting coach Richie Hebner, who “told me, ‘He’s getting a lot of guys out on fastballs, take a hack.’ I stayed behind on a changeup, missed a home run by about two inches.” The famous Green Monster, bane of many a pitcher, had taken away a round-tripper, but given Williams a two-bagger. Left field at Fenway Park is irregularly sized; hitters are seduced by the wall’s enticing presence. The 37-foot-high wall ensures that home runs are not cheap but also buoys the doubles totals for hitters.4 Until 1996, a scant 315 feet separated home from the foul pole; its distance to left-center increased to 379 feet via an almost 90-degree angle. The ballpark’s asymmetrical nature has baffled visitors; Red Sox legends bolster their bona fides by learning how to play its caroms and quirks. In his brief career, Williams enjoyed only one defensive chance while guarding the Monster; he adroitly gunned down Geno Petralli on June 21 when the Rangers catcher attempted to take second on his sharply hit line drive to left-center.

After sprinting 180 feet but disappointed at not having circled the bases, Williams did not score as Reed lined to second and Luis Rivera popped to the catcher. The Red Sox stranded what would be their best scoring opportunity in the game. In the seventh inning, Williams hit a weak grounder to Greg Gagne, who tossed the ball to Gene Larkin at first. Williams was on the on-deck circle when the game ended; Danny Heep, pinch-hitting for Romine, flied out to short right field as Jeff Reardon closed the 7-0 Twins victory.

Williams pinch-ran in a 5-4 loss to Milwaukee on June 27 and a 3-1 win over the Blue Jays on June 30. He scored the tying run in the latter game on Kutcher’s sacrifice fly off Jimmy Key, and appeared in his final game on July 2, running for Rick Cerone in the ninth inning of a 4-1 Boston victory over Toronto. He was sent back to Pawtucket in July then was traded to the Chicago White Sox on August 2 for Ray Chadwick, who had enjoyed a brief call-up with the California Angels in 1986. A right-handed pitcher, Chadwick tossed 38 frames for Pawtucket before finishing his career with the 1990 Omaha Royals. Williams appeared in four games for Triple-A Vancouver, going 5-for-15 before powering the Canadians to the circuit title over the Albuquerque Dukes.

Williams had a tough 1990 season, splitting time between the Canadians and the Double-A Charlotte Knights. He hit .258 for the year in 82 games, though he was by now an old soul, a few years older than his teammates. The Fleer baseball card company was emboldened by his minor-league accolades, picturing him as number 648 of its 1990 regular-season set. Sharing the cardboard with Rich Monteleone of the Angels, Williams appears relaxed with a shot of Fenway Park’s outfield behind him.

After taking two years off from baseball, Williams suited up for the independent Northern League Duluth-Superior Dukes in 1993. Though the team finished last in the league, he hit .297, a solid 26 points above the average batter. By then, it seemed his baseball peers had surpassed him. Younger, faster, stronger players were in the league; Frank Thomas, the AL MVP, was five years younger than Williams, while Barry Bonds, the NL’s best player, was 15 months his junior.

Players often dream of turning back the clock; for Williams, freezing time almost became a reality as he attempted to make the Pittsburgh Pirates’ 1995 roster. The devastating 1994-1995 strike wiped out one World Series and the opportunity for records to be broken; it frustrated fans everywhere who voiced their discontent through the media and their wallet. The national pastime had survived two world wars and a global depression, but it could not withstand the greed of millionaires and billionaires aloof to public opinion. For some, it represented a golden opportunity to reach the upper echelon of their profession. A few had previously tasted the glory; others had not yet quenched their thirst. While fans, owners, and striking players all espoused different opinions on the morality of their actions, no one doubted the replacement players’ love for the game. More than two decades later, the fans’ scars may have healed, but the perceived transgressions still evoke long-held passions. For every Doug Cinnella, who argued that “the Major League Baseball Players Association did nothing for minor-league players,” there was a Will Clark, who stated, “You can’t replace the top echelon of a business with the lower echelon.”5 A few of the picket-crossers, such as Rick Reed and Kevin Millar, would enjoy lasting major-league success. Others, like Williams, saw their last chance for big-league glory slip by when players and management were ordered back to the bargaining table by future Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor. Like Cinderella, their glass slippers and golden carriages turned into pumpkins. Unlike the fairy tale, their bubble was burst without warning, rather than at a much-forewarned midnight strike of the clock.

Impartial observers would be hard-pressed to fault Williams. The Red Sox could have promoted him to the majors at a younger age; they could have traded him to other clubs to address other roster needs. The Pirates were not a franchise booming with success. After enjoying three consecutive NL East crowns (1990-1992), the club had fallen in hard times. By early 1995 Bonds had departed for San Francisco; Bobby Bonilla for New York; Doug Drabek for Houston. Prospects like Orlando Merced and Al Martin did not live up to the hype; second-bananas Jeff King and Jay Bell were not able to sustain their production; Denny Neagle, while promising, was too raw. Andy Van Slyke, the sole member of the nucleus management had retained, failed to age well. Williams “did well but sat around waiting to come to Pittsburgh.” Shortly after the union and the owners agreed to a deal, he laconically told the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette “nothing has come in the way of me and my dream. My dream was to play in the major leagues. I accomplished that [eight games with the Boston Red Sox in 1989]. But I wanted to play longer.”6 Despite the disappointment of the prior spring, Williams was not yet ready to hang up his spikes. He returned to the independent Northern League, this time patrolling the outfield for the 1996 Sioux City Explorers. After hitting .254 through 30 games, he decided to call it a career.

The term “Four-A player” has been used in a pejorative sense for those hitters who cannot succeed at the major-league level but are above the highest ranking of the minors. Williams fits the criteria; while he hit .291 in the minors, he was not successful in the majors. However, he was barely in the major leagues, with only five at-bats to his credit. Other players suffer through the shuttle of round-trips between the majors and the minors, frustrating fans and front offices alike.

After his playing career, Williams found success in the dugout. “A friend in Mobile worked as the field coordinator for the Seattle Mariners; through him, I became a coach in the organization.” He began with the Lancaster JetHawks of the California League in 1997 as the hitting coach, a role he would hold through 2000. The team made the postseason in three of those campaigns but switched its affiliation to the Diamondbacks in 2001, so Williams, the players, and the coaching staff relocated to San Bernardino.

The Mariners organization promoted Williams to the Midwest League before the 2002 campaign, where the coached the Class-A Wisconsin Timber Rattlers hitters, including Adam Jones and Shin-Soo Choo, who would soon taste major-league stardom. Williams was phlegmatic about this role: “Either you can hit or you cannot. Jones could hit; leave him alone. With Choo, the power came, they kept telling him to pull the ball.” He spent the 2002, 2003, and 2004 campaigns with the team before returning in 2007. Confidence, above all, was often the missing ingredient: “I feel that my job is trying to build the confidence in the players. In baseball you try to look day-by-day. I like to look at it at-bat by at-bat. I know these guys can hit, they wouldn’t be at this level if they couldn’t.”7

Williams managed the Rookie League’s Arizona Mariners in 2005 and 2006, having tested the desert in 1998 as an assistant coach. He recalled that his biggest contribution was telling the Mariners “to put Rafael Soriano on the mound; he was a right fielder but could not hit.” He moved to the Frontier League in 2010 as the hitting coach for the Washington Wild Things. As of 2019 Williams coached high-school baseball with Penn-Trafford, near Pittsburgh, after managing East Allegheny for three years. He said he enjoyed grooming the next generation of players and regaling them with stories of his career; his charges mention “his experiences with traveling and all the unique characters he encountered along the way are great. He has a lot of funny stories about the bus rides and other experiences. It’s pretty cool to hear stories about some of the big leaguers and people you’ve heard of before.”8

Last revised: August 1, 2021

Acknowledgments

Dana Williams for graciously agreeing to an interview with the author.

Kerry Sean Hetrick, athletic director of Penn-Trafford High School, and Dan Miller, baseball head coach of Penn-Trafford High School, for connecting the author to Dana Williams.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author relied extensively on Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Author interview with Dana Williams on September 5, 2019. Unless otherwise specified, all quotations come from this interview.

2 Major League Baseball player figures at the conclusion of 2019 (baseball-reference.com/leagues/) and place of birth (baseball-reference.com/bio/).

3 1982 Draft Results, January Secondary Draft, https://mlb.mlb.com/mlb/history/draft/draft.jsp#season=1982&player_name=&draft_type=NS&draft_team=&draft_round=&page=1&sort_order=&sorted_by=.

4 Left-center field at Fenway Park was listed as 315 feet from home plate from 1936 through 1995 but has been listed as 310 feet since 1995. mlb.com/redsox/ballpark/facts-figures; https://www.baseball-almanac.com/stadium/fenway_park.shtml.

5 Steven Marcus, “Twenty years ago, replacement players almost opened baseball season,” Newsday, March 28, 2015. https://newsday.com/sports/baseball/twenty-years-ago-replacement-players-almost-opened-baseball-season-1.10142935.

6 Chuck Finder, “Back to Reality,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, April 27, 1995: E-13, E-14.

7 The Minor Leaguers of 1990: Greatest 21 Days, https://greatest21days.com/2012/10/dana-williams-higher-level-651.html.

8 Joe Sager, “Penn Trafford Baseball Gets Boost from Former Pro Dana Williams,” TribLive High School Sports Network, May 27, 2019. https://tribhssn.triblive.com/penn-trafford-baseball-gets-boost-from-former-pro-dana-williams/.

Full Name

Dana Lamont Williams

Born

March 20, 1963 at Weirton, WV (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.