Dinny McNamara

Personal problems rooted in a car accident stopped Dinny McNamara from fulfilling what might have been a legendary Boston sporting career. Still, before his troubles intervened, McNamara became a multisport high-school and college star, an outfielder with the 1927 and ’28 Boston Braves, and head football coach at Boston College – all before his 30th birthday.

Personal problems rooted in a car accident stopped Dinny McNamara from fulfilling what might have been a legendary Boston sporting career. Still, before his troubles intervened, McNamara became a multisport high-school and college star, an outfielder with the 1927 and ’28 Boston Braves, and head football coach at Boston College – all before his 30th birthday.

John Raymond McNamara was born on September 16, 1905, in Lexington, Massachusetts, the Boston suburb that hosted the first battle of the Revolutionary War 130 years earlier.1 As of 2024, he remained the only major leaguer to list Lexington as his birthplace. He was the son of Dennis McNamara, a stonemason, and Catherine (Lynch) McNamara, both first-generation Americans of Irish ancestry.2 At the time of the 1910 Census, the McNamaras had had eight children, of whom five were living. By 1920, they had added two more.3

Young McNamara quickly set himself apart as a star athlete. At age 15, he pitched a no-hitter for a local church’s youth team against a team from South Boston.4 His nickname Dinny – the origin of which was not explained5 – first appeared in Lexington’s weekly newspaper in January 1922, when he was cited as “the outstanding star” in a scrimmage between Lexington High School’s first- and second-string basketball teams.6

The Boston Traveler newspaper singled out quarterback McNamara as an “extraordinary performer” and “a college prospect” on the Lexington High football team.7 Ice hockey has long been popular in Massachusetts, and McNamara was good at that too, scoring two goals in a fiercely fought tie game between teams from the towns of Lexington and Lynnfield.8

Graduating as vice president of Lexington High’s Class of 1922,9 McNamara moved on to one of New England’s biggest athletic powers, Boston College. Despite his small size – listed in Baseball-Reference as 5-feet-9 and 165 pounds10 – McNamara played four seasons of football at BC. He lost out to teammate Joe McKenney in a competition to start at quarterback, but McNamara’s speed made him a useful “mighty mite”-type player at several positions.11

The Boston Globe praised McNamara’s pass-catching abilities, called him “the flash of the outfit” and “the BC speed demon,” and added that he could “turn in a good day’s work at either quarterback or fullback.”12 Under coach Frank Cavanaugh, the Eagles posted an undefeated 6-0-2 record in 1926.13 Cavanaugh reportedly called McNamara “the greatest football player that has ever represented the Maroon and Gold.”14

McNamara also spent three years on BC’s baseball team.15 A starter in center field, he was chosen as captain for his senior season in a vote of the team taken at Fenway Park after a game against the College of the Holy Cross. As a junior, McNamara was described as “one of the fastest players in the college ranks,” with a 16-game hitting streak made possible in part by his ability to leg out bunts from the left-hand side of the plate.16 (McNamara batted left and threw right.) The Globe described the Eagles’ outfield that year as “the best in collegiate circles not only for hitting but for fielding.”17

McNamara continued to shine in his senior year. In a game against Syracuse University, he went 2-for-3, scored three runs, and stole second, third, and home in a single inning.18 “Dinny can play any sport, any time and anywhere from 100 to 101 percent perfect,” the BC student newspaper raved. “When this captain runs around the bases he makes a split-second watch look like an hourglass.”19 He was reported to be hitting around .400 near the end of his senior season,20 and rumors had him signing either with the hometown Braves or the Cincinnati Reds.21 In his final collegiate game, against Holy Cross, McNamara singled, doubled, and tripled in five at-bats and scored the winning run in the 11th inning.22 A comment in his senior yearbook summed up his career at Boston College: “He came unheralded. He is leaving famous.”23

Less than a week after that final game, McNamara signed with the Braves; whether the Reds truly had a chance to pry him away from Boston is an open question. The Braves’ owner, Judge Emil Fuchs, described McNamara as “the outstanding college player of the country,” according to one news story that gave his senior-season batting average as .459.24

After starting in center field in an exhibition game on June 28,25 McNamara made his big-league debut as a pinch-runner in the second game of a doubleheader against the New York Giants on July 2. Sent in for left fielder Eddie Brown in the 10th inning, McNamara scored the winning run on Eddie Moore’s bunt single as the Braves won, 2-1, in front of a hometown crowd at Braves Field.26

The rookie’s next six appearances also came as a pinch-runner. He finally got the chance to start three games in center field against the Reds – a single game on July 19 and a doubleheader on July 20 – but went a combined 0-for-9 with three strikeouts. After one more pinch-running appearance, against Pittsburgh on July 22, McNamara was sent to Providence of the Class A Eastern League, where he batted .244 in 51 games.27

McNamara’s Boston College baseball coach, Jack Slattery, replaced Dave Bancroft as Braves manager for the 1928 season. This did not prove advantageous, as Slattery didn’t give McNamara any more playing time than his predecessor had. Through May 23, McNamara played in only seven games and was given only one start. He started in center field against the Brooklyn Robins on April 26 and went 1-for-3, collecting his only major-league hit, an infield single against future Hall of Famer Dazzy Vance. McNamara was later caught trying to steal second base, but the Braves won, 4-0.

Slattery resigned on May 23, under pressure to make way as manager for offseason acquisition Rogers Hornsby.28 Hornsby gave McNamara only two more pinch-running opportunities, the latter in the first game of a May 30 doubleheader against the Philadelphia Phillies at Baker Bowl. McNamara’s final major-league appearance went much the same as his first: Running for catcher Zack Taylor in the 10th inning, McNamara scored what proved to be the winning run on Lance Richbourg’s single in a 5-3 Braves victory. Five days later, the Braves sent Dinny back to Providence, where he hit just .222 in 95 games.29

McNamara’s idiosyncratic usage led to an unusual career line: 20 games played, 13 at-bats, one hit (for an .077 average), five runs scored, four strikeouts, three sacrifices, and one unsuccessful stolen-base attempt.30 He handled 17 fielding chances flawlessly. Modern statistical measures give him a Wins Above Replacement total of -0.4.

McNamara and fellow Lexington ballplayer Tom Fitzgerald spent the 1929 and 1930 summers playing for Osterville in the Cape Cod League,31 but there’s no indication that McNamara played professional baseball after 1928. By the fall of 1929, he had returned to football, signing on as an assistant coach and advance scout under Cavanaugh, who had moved on to Fordham University.32 McNamara was on hand at Fenway Park on November 9, 1929, when Fordham snapped Boston College’s 17-game unbeaten streak with a 7-6 victory in front of more than 25,000 fans.33 That summer, McNamara had served as an usher at the wedding of Joe McKenney. McNamara’s former baseball teammate and rival for the starting quarterback job had become BC’s head football coach.34

McNamara spent four years with Fordham as a scout and staffer until ill health forced Cavanaugh to retire in December 1932.35 Dinny also taught and coached at a high school in Brooklyn during this period.36 After Cavanaugh retired, Fordham released McNamara from its football staff; McKenney snapped him up as an assistant coach at Boston College.37 McKenney moved on to a new job in February 1935, and recommended McNamara as his successor. BC made the appointment official a few weeks later.38

The Boston Globe predicted great things, depicting McNamara as a canny, football-shrewd leprechaun. “The fair blue of his Irish eyes and the strange quirk of his Irish smile curtain one of the keenest minds in football,” sportswriter Jerry Nason wrote. Nason added that McNamara had “personality in gobs,” was “happy-go-lucky” and perpetually smiling.39

But McNamara’s future was not as bright as expected, apparently due to the aftereffects of an accident two years earlier. On the early morning of January 17, 1933, McNamara’s car skidded off the road on Waltham Street in Lexington and hit a tree. Passing truck drivers took him to a nearby hospital, where he was believed to have suffered a fractured skull, broken jaw, and severe cuts to the head.40 The specific impacts of the accident on McNamara are difficult to gauge – newspaper descriptions of his later problems are vague and inconsistent. Still, the long-term effects of the crash were subsequently blamed for difficulties in McNamara’s life.

The McNamara coaching era at Boston College got off to a turbulent start. Dinny was absent from his team’s first practice, on August 28, and rumors immediately began circulating that health problems would force him to resign before he had coached a game.41 Nason, who had touted McNamara’s upbeat nature in the spring, reported at summer’s end that the coach had been found at a local boarding house suffering from “a nervous ailment which has gripped him on and off all summer.”42

McNamara was able to start the season, but his tenure lasted only four games. The Eagles beat St. Anselm, lost to Fordham, upset heavily favored Michigan State, and beat New Hampshire.43 McNamara handed in his resignation on October 30. Printed quotes by the college’s athletic director did not give a reason, but the BC campus newspaper reported that McNamara had been “in a serious nervous condition” for several weeks and had been “affected by an ailment since a serious accident two years ago.”44 An Associated Press story gave the same explanation.45

For most purposes, McNamara disappeared from the public eye after his resignation from Boston College. The Lexington newspaper mentioned his appearances at a few events in town in the mid-1930s, and reported in September 1936 that he was taking a scouting trip to the Midwest on behalf of the Brooklyn Dodgers, the Detroit Lions football team, and several colleges.46

This may have been his last involvement with sports. An article written after McNamara’s death almost 30 years later said that he “never again figured in the Boston sports picture” after leaving BC. The article also mentioned “emotional problems” brought on by his injuries from the auto accident.47 In October 1936, a Lowell Sun columnist asked, “Whatever became of Dinny McNamara?”48

McNamara’s problems – characterized in a different way – were cited in a criminal incident in 1940. On August 2, McNamara held up a gas station in Concord, Massachusetts, hit the attendant in the head, and stole $10 and a car. He was arrested in Lowell, Massachusetts, an hour later. McNamara was committed to the Boston Psychopathic Hospital for 10 days for observation. He later pleaded guilty to robbery and larceny of an automobile and was sentenced to a year in state prison. “McNamara testified he had suffered a head injury in an auto accident several years ago that caused him frequent memory lapses,” a wire-service report summarized.49 According to another story, McNamara told police he had no memory of the incident.50

Articles about the gas station holdup mentioned that McNamara had been serving as a private in the 10th Field Artillery of the US Army, stationed at Newport, Rhode Island, and New London, Connecticut.51 A John McNamara can be found in the 1940 US Census, stationed at Fort Adams in Newport. Like Dinny, the McNamara in the Census listing was 34 years old in the spring of 1940, had never married, was a college graduate, and had lived in Lexington, Massachusetts.52

The Census offers no other hint as to McNamara’s activities after leaving BC. He was apparently a longtime resident of the family home at 2377 Massachusetts Avenue, Lexington: That address was listed in articles about his car accident in 1933 and his funeral 30 years later; it is also on his death certificate.53 However, the 1950 Census listing for the McNamara family at that address does not include him.54

He might have moved out for a time – or he might have been institutionalized. An entry in the 1950 Census finds a John McNamara living at the Francis Farris Memorial Hospital in Lowell, described on the Census form as “Home for the Aged & Needy, Chronic & Incurable.”55 While it can’t be proven that this was the former athlete and coach, the scant information available for the hospital resident – 44 years old, never married, born in Massachusetts – is a match for Dinny.56

Boston-area newspapers also reported on a family tragedy that could only have added to McNamara’s burden in the post-BC years. On November 22, 1942, Dinny’s nephew Edward Jr. and another young man were killed in a car crash on Massachusetts Avenue in Lexington. Their car left the road and hit a tree, as Dinny’s had nine years earlier. Edward Jr. was 17 years old, a junior at Lexington High School, and a star fullback on the football team.57

Car accidents had changed McNamara’s life for the worse. In the waning days of 1963, another accident ended his life. Shortly after 5 P.M. on December 20, 1963 – almost an hour after sunset, on a frigid, windy day58 – McNamara was hit by a car and killed while walking on Waltham Street in Lexington, the same road where his 1933 accident occurred.59 He was 58 years old and was survived by a brother and four sisters. Following services at St. Brigid’s Church in Lexington, he was buried in St. Bernard’s Cemetery in nearby Concord.60

McNamara’s death certificate listed his occupation as a retired coach at Boston College, further supporting the perception that his promising career had stilled to silence in the latter half of his life.

Acknowledgments

This story was reviewed by Rory Costello and Len Levin and checked for accuracy by SABR’s fact-checking team.

Sources and photo credit

In addition to the sources credited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org for background information on players, teams, and seasons. The author thanks the Giamatti Research Center of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum for research assistance, and thanks the Cary Memorial Library of Lexington, Massachusetts, for making its archive of local newspapers freely available online.

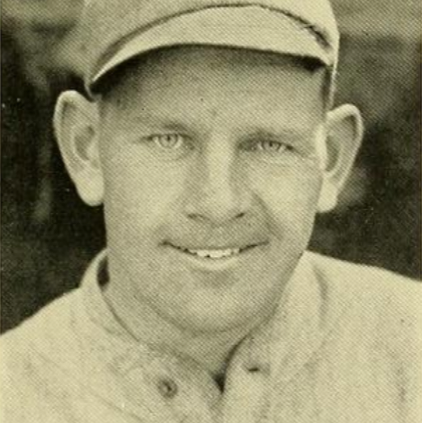

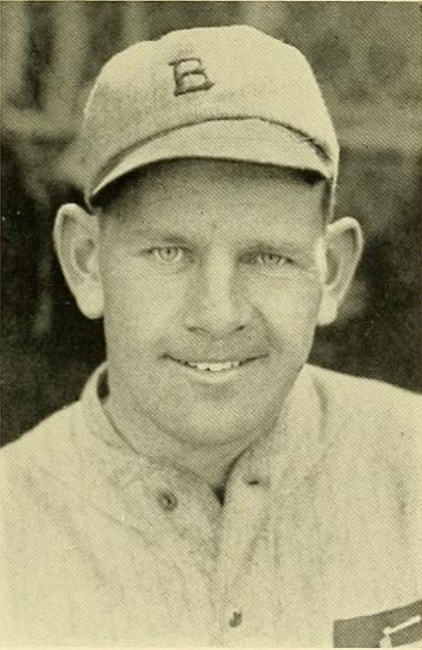

Photo from the 1927 Sub Turri Boston College yearbook: 373. https://archive.org/details/subturriundertow1927bost/page/372/mode/2up?view=theater

Notes

1 Fighting between British soldiers and colonial residents at Lexington on April 19, 1775, preceded the skirmishing at Concord later that day. “April 19, 1775,” Minute Man National Historical Park website, accessed February 2024. https://www.nps.gov/mima/learn/historyculture/april-19-1775.htm.

2 1910 US Census listing for the McNamara family, accessed via Familysearch.org in January 2024. The 1910 and 1920 Censuses spell Mrs. McNamara’s name Katherine, but other sources spell it Catherine, including newspaper obituaries: “Mrs. Catherine McNamara,” Lexington (Massachusetts) Minute-Man, March 11, 1943: 5, and “Catherine McNamara,” Boston Globe, March 8, 1943: 9. Dinny McNamara’s death certificate – for which his sister, Theresa, provided information – also spells it Catherine. McNamara’s death certificate is available as part of his clip file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum’s Giamatti Research Center.

3 1910 Census and 1920 Census listings for the McNamara family, accessed via Familysearch.org in January 2024.

4 “Lexington Locals,” Lexington Minute-Man, June 10, 1921: 1. The local church in question, St. Brigid’s, was the site of McNamara’s funeral service in December 1963.

5 “Dinny” is an Irish diminutive of Dennis – McNamara’s father’s first name – and it’s possible that “Dinny” was coined as a way of calling the boy “Little Dennis.”

6 “Lexington Locals,” Lexington Minute-Man, January 20, 1922: 1. McNamara’s page in the 1927 Boston College Sub Turri yearbook described “Dinny” as “the readily adopted nickname of uncertain origin.”

7 “Lexington High School Football Record,” Lexington Minute-Man, December 16, 1921: 8. The Lexington paper reprinted an article that had appeared in the Boston Traveler the previous week.

8 “Lexington Ties Lynnfield,” Lexington (Massachusetts) Times, February 15, 1924: 7.

9 “Lexington H.S. Graduation,” Lexington Minute-Man, June 23, 1922: 8.

10 One article from McNamara’s college days spotted him an extra inch, listing him as 5-feet-10 and 162 pounds. “Brief Sketches of B.C. Players,” Boston Globe, November 28, 1924: 20.

11 Sub Turri (“Under the Tower”), Boston College yearbook, 1927: 188. https://archive.org/details/subturriundertow1927bost/page/188/mode/2up?view=theater.

12 “Visitors Boast Flashy Backs,” Boston Globe, October 11, 1926: 17; “B.C Looks to Hard Tilt with Indians,” Boston Globe, November 12, 1926: 27; “Boston College’s All-Around Star Back Expected to Shine Saturday,” Boston Globe, November 25, 1926: 21. The first of these stories previewed a Boston College-Fordham University matchup played at Braves Field.

13 2023 Boston College football media guide: 126. https://bceagles.com/documents/2023/8/21/2023_BC_Football_Media_Guide.pdf

14 Sub Turri, Boston College yearbook, 1927: 369.

15 Sub Turri, Boston College yearbook, 1927: 188.

16 “McNamara Elected to Captain Eagles,” Boston Globe, June 18, 1926:

17 “B.C. Batters to Face Test,” Boston Globe, May 28, 1926: 20.

18 “Syracuse Defeated by Boston College,” Boston Globe, May 19, 1927: 21. McNamara’s football rival Joe McKenney, playing left field, hit a home run in this game.

19 “Captain ‘Dinny’ Impatiently Waiting for Time to Workout on Alumni Field,” The Heights (Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts), February 22, 1927: 1. https://newspapers.bc.edu/?a=d&d=bcheights19270222&e=——-en-20–61–txt-txIN-%22dinny+mcnamara%22——.

20 “Eagles and Purple in Second Clash,” Boston Globe, June 11, 1927: 10;

“Collegiate Batting Drops,” Boston Globe, June 11, 1927: 9. The Globe had McNamara hitting as high as .463 a few weeks earlier: “Holy Cross Nine Slight Favorite to Defeat Boston College Nine Monday,” May 28, 1927: 6.

21 Melville E. Webb Jr., “Persistent Rumor Denny McNamara of B.C. May Sign Pro Baseball Contract,” Boston Globe, June 14, 1927: 21. The Globe generally spelled McNamara’s nickname as “Denny” during his college years.

22 “McNulty Beats Crusaders in 11 Despite Misplays,” Boston Globe, June 15, 1927: 24.

23 Sub Turri Boston College yearbook, 1927: 188.

24 James J. Murphy, “Pitching Has Improved Despite Work of Boys with the Hefty Wallop,” Brooklyn Eagle, June 21, 1927: 2A.

25 “Braves Bunch ’Em in the Eighth,” Boston Globe, June 29, 1927: 14. The Braves played the Lynn, Massachusetts, team of the Class B New England League in Lynn. McNamara went 1-for-4.

26 It was not an especially large crowd: Only about 8,500 fans attended.

27 Associated Press, “Dozen Straight Upon Short End for Grays,” Portland (Maine) Sunday Telegram and Sunday Press Herald, July 24, 1927: B2.

28 Bill Nowlin, “Jack Slattery,” SABR Biography Project, accessed January 2024. https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/Jack-Slattery/.

29 Associated Press, “Player Released,” Montpelier (Vermont) Evening Argus, June 5, 1928: 7.

30 McNamara is on record as making only one – unsuccessful – attempt to steal a base in his brief big-league career. Braves managers might have esteemed McNamara’s speed, but they didn’t give him carte blanche on the basepaths.

31 “Sport Notes,” Lexington Times-Minute-Man, July 19, 1929: 4; “News of Your Neighbors,” Lexington Times-Minute-Man, July 4, 1930: 4.

32 “Fordham Team in Fine Trim,” Boston Globe, November 8, 1929: 25; Murray Robinson, “As You Like It,” Brooklyn Standard Union, November 22, 1929: 12.

33 Score and length of unbeaten streak from 2023 Boston College football media guide: 112. As for the attendance, one New York paper had it at 30,000, while the Boston College student paper said 27,000. “Fordham Downs Boston College by 7 to 6 Score,” Brooklyn Daily Times, November 10, 1929: 1A; “Fordham Spoils Eagles’ Record,” The Heights, November 12, 1929: 1. https://newspapers.bc.edu/?a=d&d=bcheights19291112.2.10&e=——-en-20–1–txt-txIN——-.

34 “B.C. Coach Marries Miss Alice Ryan,” Boston Globe, June 26, 1929: 5.

35 Hy Hurwitz, “Dinny Wants to Beat Rams,” Boston Globe, October 2, 1935: 23; Jimmy Powers, “Cavanaugh Resigns!” New York Daily News, December 20, 1932: 46.

36 “Lexington Athlete Given Sendoff,” Boston Globe, January 25, 1930: 2.

37 Hurwitz, “Dinny Wants to Beat Rams.”

38 Associated Press, “Joe McKenney Takes Post in Physical Education Department of Boston Schools,” Hartford (Connecticut) Daily Courant, February 19, 1935: 17; United Press, “McNamara Named to Succeed Joe McKenney,” Miami Herald, March 8, 1935: 1B.

39 Jerry Nason, “‘Dinny Mac’ Knows His Football,” Boston Globe, March 8, 1935: 18.

40 “McNamara Is Badly Injured,” Boston Globe, January 17, 1933: 5; “John ‘Dinny’ McNamara Injured in Auto Accident,” Lexington Townsman and Times-Minute Man, January 19, 1933: 1.

41 “B.C. Grid Squad Now in Training,” Burlington (Vermont) Free Press and Times, August 29, 1935: 13.

42 Jerry Nason, “Downes May Get B.C. Job,” Boston Globe, August 30, 1935: 11.

43 United Press, “National Grid Picture Knocked Cock-eyed by Surprises,” Muskogee (Oklahoma) Daily Phoenix, October 21, 1935: 6; 2023 Boston College football media guide: 113. The guide misspells McNamara’s first name as “Dinney.”

44 “Downes Appointed Football Coach; To Succeed McNamara,” The Heights (Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts), November 1, 1935: 1. https://newspapers.bc.edu/?a=d&d=bcheights19351101&e=——193-en-20–1–txt-txIN-%22dinny+mcnamara%22——. One news report blamed McNamara’s “nervous disorder” on “an old football injury,” but most stories about McNamara’s woes linked them to the car accident. International News Service, “Dinny McNamara Forced to Resign as Grid Coach,” Paterson (New Jersey) Evening News, October 30, 1935: 54.

45 Associated Press, “Downes One of Youngest Grid Coaches in U.S.,” Burlington (Vermont) Daily News, October 31, 1935: 8.

46 “McNamara Scouting for Colleges and Clubs,” Lexington Minute-Man, September 17, 1936: 7. It should be noted that the fledgling National Football League had a team called the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1936. The context of the article suggests McNamara was working for the baseball Dodgers, but the author might have misunderstood.

47 Arthur Siegel, “How Dinny McNamara’s Eagles Beat Mich. State,” Boston Globe, December 24, 1963: 14.

48 John F. Kenney, “The Lookout,” Lowell Sun, October 3, 1936: 11. https://access-newspaperarchive-com.ezproxy.bpl.org/us/massachusetts/lowell/lowell-sun/1936/10-03/page-59/.

49 “Ex-Coach at B.C. Sent to Hospital for Observation,” Boston Globe, August 3, 1940: 2; United Press, “McNamara Jailed on Theft Charge,” Waterbury (Connecticut) Evening Democrat, October 16, 1940: 16. The Boston Psychopathic Hospital is now known as the Massachusetts Mental Health Center. “Ask the Globe,” Boston Globe, February 12, 1980: 40.

50 “Bandit Suspect Is Held for Mental Exam,” Lowell Sun, August 3, 1940: 1. https://access-newspaperarchive-com.ezproxy.bpl.org/us/massachusetts/lowell/lowell-sun/1940/08-03/page-27/.

51 “Ex-Coach at B.C. Sent to Hospital for Observation.” McNamara’s presence in the Army suggests that his personal problems, whatever their nature, were not onerous enough to prevent him from military induction and service prior to the gas station incident.

52 1940 US Census listing for John McNamara, accessed through Familysearch.org in January 2024. Since the Census is conducted in the spring, the information in it would have been gathered before the gas station incident.

53 “McNamara Is Badly Injured”; “John R. McNamara,” Lexington Minute-Man, December 26, 1963: 2A; “Ex-B.C. Coach J.R. McNamara,” Boston Globe, December 23, 1963: 22; Dinny McNamara death certificate.

54 1950 US Census listings for the McNamara family of 2377 Massachusetts Avenue, Lexington, accessed via Familysearch.org in January 2024. Dinny McNamara is also not listed with his family in the 1940 US Census, but that discrepancy is addressed above in the discussion of his service as a soldier.

55 Francis Farris Memorial Hospital, formerly known as the Chelmsford Street Hospital, began its existence as the city of Lowell’s poor farm. In the first half of the 20th century, the hospital offered a home to the indigent and those suffering from mental illness or alcoholism. The hospital closed in 1958. Gregory Gray Fitzsimmons, Changing Course: A History of River Meadow Brook (Lowell Land and Conservation Trust, Lowell, Massachusetts: 2013): 224. https://lowelllandtrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Changing_Course_A_History_of_River_Meadow_Brook_Final.pdf.

56 1950 US Census listing for John McNamara in Francis Farris Memorial Hospital, accessed via Familysearch.org in January 2024. Lowell and Lexington are both located in Middlesex County, Massachusetts.

57 “Auto Crash Kills 2 Lexington Youths, One a Football Star,” Boston Globe, November 23, 1942: 1.

58 The sun set in the Boston area at 4:13 P.M. that day, according to the weather update on the upper right-hand corner of Page 1 of the Boston Globe’s morning edition of December 20, 1963.

59 The Lexington Minute-Man’s short article on McNamara’s death, cited above, sets the time of the accident at 5:08 P.M. McNamara’s death certificate lists the time of the accident as about 6:30 P.M. Neither the Boston Globe nor the Lexington paper made any reference to charges being filed against the driver.

60 “McNamara” (death listing), Boston Globe, December 23, 1963: 22; “John R. McNamara,” Lexington Minute-Man, December 26, 1963: 2A.

Full Name

John Raymond McNamara

Born

September 16, 1905 at Lexington, MA (USA)

Died

December 20, 1963 at Arlington, MA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.