Frank Selee

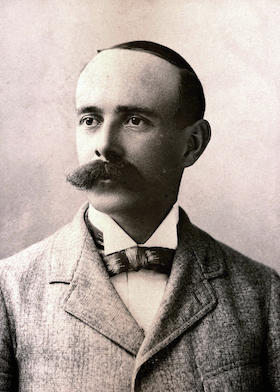

A small, mild-mannered, prematurely bald man with a prominent mustache, Frank Selee looked more like an insurance underwriter than a baseball manager, especially in team photos next to his strapping young athletes. Nevertheless, he was one of the most successful field leaders of his era, directing the Boston Beaneaters to five National League pennants between 1891 and 1898. Later, he assembled the Chicago Cubs team that won four pennants and two World Series titles during the following decade. Selee, whom Sporting Life described in 1893 as “a manager who is a thorough baseball general … who knows what should be done and how to do it, and is able to impress his advice upon the men under his control,”1 was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1999, 90 years after his death.

A small, mild-mannered, prematurely bald man with a prominent mustache, Frank Selee looked more like an insurance underwriter than a baseball manager, especially in team photos next to his strapping young athletes. Nevertheless, he was one of the most successful field leaders of his era, directing the Boston Beaneaters to five National League pennants between 1891 and 1898. Later, he assembled the Chicago Cubs team that won four pennants and two World Series titles during the following decade. Selee, whom Sporting Life described in 1893 as “a manager who is a thorough baseball general … who knows what should be done and how to do it, and is able to impress his advice upon the men under his control,”1 was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1999, 90 years after his death.

Frank Gibson Selee was born in Amherst, New Hampshire on October 26, 1859, the oldest child of Nathan and Annie Selee. Nathan Selee had taught school before becoming a Methodist preacher one year before the birth of his first son. In 1864, Nathan moved the family to Melrose, Massachusetts, about eight miles north of Boston. Frank played the outfield for the main town team in Melrose, the Alphas, though he possessed more enthusiasm than talent. While in his early twenties, he decided to focus his talents on organizing, not playing, the game.

In 1884, he left a job at a watch company to organize the new Waltham team in the Massachusetts State League. He signed players and raised $1,000 to provide the playing field with seats and a fence. Despite Frank’s hard work, the Waltham franchise collapsed after a few months, and he and several of his players moved to Lawrence to finish the season. He played the outfield a few times that year, and those contests represent Frank Selee’s entire professional playing career.

In 1885 and 1886, Frank managed at Haverhill in the New England League. He was hired by Oshkosh of the Northwest League in 1887, and convinced the team owners to sign outfielder Tommy McCarthy, who had won the batting title for Brockton, and pitcher Tom Lovett, a 32-game winner for Newburyport and Lynn.

Frank also took a chance on William (Dummy) Hoy, a speedy 24-year-old former shoemaker from rural Ohio. Hoy, who was deaf (the nickname “Dummy” was not considered a pejorative at the time), played for Oshkosh in 1886, but batted only .219. Selee retained Hoy for the 1887 season and devised ways to make it easier for him to play. As an 1888 article explained, “[Hoy] is left handed, and when he bats a man stands in the captain’s box near third base and signals to him decisions of the umpire on balls and strikes by raising his fingers.”2 This may have been the first use of ball-and-strike signals on the baseball field; it was years before umpires adopted the practice. Hoy played centerfield and batted .367, while McCarthy hit .345. Frank won his first pennant over Jim Hart’s Milwaukee club.

The directors of the Omaha club in the Western Association offered Frank a reported $3,000 to move his Oshkosh team en masse to Omaha. Tom Lovett made the move to Nebraska, but McCarthy and Hoy advanced to the major leagues and left Frank with holes in his lineup. Though Lovett won 30 games, Omaha finished in fourth place in 1888, with a 55-48 record. Lovett then left to join Brooklyn of the American Association, but Frank identified another outstanding pitching prospect. Charles (Kid) Nichols was an 18-year-old right-hander who had posted a 16-2 record for Kansas City in 1888. Kansas City won the Western Association pennant that year, then joined the American Association and decided not to sign Nichols for the 1889 campaign. Selee hired Nichols and installed the slender teenager as the team’s premier starting pitcher.

Nichols posted an incredible 39-8 record and led Omaha to the Western Association pennant, Frank Selee’s second as a manager. Omaha’s 83-38 record and .686 winning percentage were the best in all of organized baseball that year. The National League’s Boston Beaneaters signed Nichols to a contract for the following year, while William Conant, one of the three Boston club owners, persuaded the other two Triumvirs (as the papers called them) to hire Selee as well. In late 1889 Selee, who lived year-round in Melrose, became the manager of the nearby Boston ballclub.

Most of Boston’s stars, except for pitcher John Clarkson and catcher Charlie Bennett, had jumped to the new Players League, leaving the Beaneaters short of talent. However, nearly every other National League team was in the same predicament, and the exodus removed several strong-willed and hard-drinking veterans from Selee’s roster. Mike (King) Kelly, the most popular player in the game, had undermined Jim Hart’s authority as manager in 1889, and Kelly’s jump to the rival league left Selee free to manage with no interference from the game’s biggest star.

Selee, the son of a minister, was not a drinker, in contrast to almost all other managers of his day. Frank was a soft-spoken man who relied on preparation, not force, to lead his players. “If I make things pleasant for the players, they reciprocate,” Selee once explained. “I want them to be temperate and live properly. I do not believe that men who are engaged in such exhilarating exercise should be kept in strait jackets all the time, but I expect them to be in condition to play. I do not want a man who cannot appreciate such treatment.”3 He transformed the Beaneaters from a wild, hard-drinking crew into a team that relied on intelligence and execution to win games.

Kid Nichols stepped in as a starting pitcher, and Selee persuaded the Triumvirs to sign Milwaukee second baseman Bobby Lowe and Kansas City shortstop Herman Long. Long became a star at shortstop, Nichols won 27 games as a rookie, and Lowe filled in ably as a utility man. While Kelly and the Boston Players League squad won the pennant in the rival circuit, Selee brought the Beaneaters home in fifth place in the National League during his first season.

The Players League collapsed after one season, and third baseman Billy Nash and right fielder Harry Stovey returned to the Beaneaters. These stars solidified Selee’s lineup and boosted Boston into the pennant race in the early stages of the 1891 season. By August, the Beaneaters stood alone in second place behind Cap Anson’s Chicago squad, but later that month King Kelly returned to Boston and provided the spark that Selee’s club needed. Chicago defeated Boston twice in mid-September, but then Selee’s men ran off an 18-game winning streak (including one tie) and finished the race three games in front of Chicago. In Frank Selee’s second season as Boston manager, he won the team’s first league championship since 1883. When the American Association collapsed that winter, the Beaneaters acquired two future Hall of Famers, outfielder Hugh Duffy and the star of Selee’s Oshkosh pennant-winners, Tommy McCarthy.

Team chemistry was paramount to Selee, and the manager made sure not to sign anyone who might disrupt the harmony of the ballclub. Reflecting upon his Boston experience, Selee once said, “It was my good fortune to be surrounded by a lot of good, clean fellows who got along finely together. To tell the truth, I would not have anyone on a team who was not congenial.”4 King Kelly was a behavioral nightmare and a hard drinker, but by the end of the 1891 season the Beaneaters were Selee’s team and not Kelly’s.

Kelly’s presence electrified the fans and the local sportswriters, but he batted only .231. The next year, Kelly batted .189 as a part-time player. John Clarkson, too, was fading; he won 33 games in 1891, but when he complained of a sore arm in early 1892, the Beaneaters released him and replaced him with Jack Stivetts, another signee from the defunct Association. Stivetts and Nichols posted identical 35-16 records in 1892 as the Beaneaters won 102 games, becoming the first team in history to win 100 in a season.

The 1892 campaign marked the first and last instance (until 1981) of a split-season pennant race. Boston easily won the first half, but the Cleveland Spiders rallied in mid-season and won the second. In the end, Boston handily defeated Cleveland in their October matchup. Jack Stivetts and Cleveland’s Cy Young battled to an 11-inning scoreless tie in the first game, but Selee’s team won the next four contests and captured their second pennant in a row.

Selee valued players with brains as well as brawn, and trusted his men to make the right decisions. “He was a good judge of players,” said Bobby Lowe. “He didn’t bother with a lot of signals, but let his players figure out their own plays. He didn’t blame them if they took a chance that failed. He believed in place-hitting, sacrifice-hitting, and stealing bases. He was wonderful with young players.”5 Under Selee, the Beaneaters refined the hit-and-run to a science. Monte Ward watched the Boston team with amazement. “I have never, in my twelve years’ experience on the diamond, seen such skillful playing,” said Ward in 1893. “The Boston players use more head-work and private signals than any other team in the country.”6

Selee moved Bobby Lowe from the outfield to second base in 1892, and Lowe teamed with Herman Long to form a keystone combination that stayed together for nearly 10 years. In 1893, Selee’s men held off the Pittsburg Pirates and won their third pennant by a five-game margin. The Boston dominance ended in 1894, when injuries, holdouts, and the emergence of the Baltimore Orioles drove the Beaneaters to a third-place finish, eight games behind.

Selee convinced the Triumvirs not to tear the team apart, but to refine it. He kept Long and Lowe at short and second, but sent third sacker Billy Nash to Philadelphia for outfielder Billy Hamilton. On a trip to Buffalo, Selee noticed a young third baseman named Jimmy Collins and brought him to Boston. Collins stumbled early on, and the Triumvirs demanded that Selee get rid of the youngster, but Selee farmed him out to Louisville for more experience. In 1895 Selee brought Collins back to Boston, where the young man completed the new Boston infield.7

Hugh Duffy remained, but Tommy McCarthy began to slow down in his mid-thirties, so Selee released his longtime favorite and put Hamilton in center, with Duffy in left and newcomer Chick Stahl in right. The pitching staff featured Kid Nichols, Jack Stivetts, and two new faces, left-hander Fred Klobedanz and right-hander Ted Lewis. The career of catcher Charlie Bennett ended in a train accident in 1894, but Selee found a talented replacement in Marty Bergen. The Orioles won three pennants in a row from 1894 to 1896, but the revamped Beaneaters stood ready to challenge again for the flag in 1897.

Selee’s retooled ballclub jumped out to an early lead, but Baltimore stayed close all season long. In mid-September the two teams met in a three-game series to decide the pennant. Nichols won the first game for Boston. Lewis lost the second, and set the stage for one of the greatest games of the nineteenth century. On September 25, 1897, more than 25,000 people packed the Baltimore ballpark and watched Kid Nichols stagger to a 19-10 win over the Orioles. This victory virtually clinched Selee’s fourth pennant and established Boston once again as the dominant team of the National League.

Jack Stivetts’ mound career was crippled in 1898 by a sore arm, but Selee located another outstanding young pitcher. Vic Willis was a tall curveball specialist who posted a 20-17 mark for Syracuse in 1897, and Selee convinced the Boston owners to buy the pitcher’s release for $3,000. Willis impressed the Boston observers with his overhand curve, but he needed work on his control, so Selee hired Jack Ryan, a retired catcher, who built a wooden target for Willis to practice against. Before long Willis began to get his pitches over the plate, and he joined the rotation in May. Willis posted a 25-13 record in able support of Nichols (31-12) and Lewis (26-8), and Selee’s Beaneaters rolled to their fifth pennant in eight years.

The core of the team began to unravel in 1899. Nichols fell to a 21-19 record, Hamilton slowed down due to leg injuries, and stars such as Lowe, Long, and Duffy all were showing their age. The Brooklyn Dodgers ran away with the 1899 pennant as the fading Bostons held second place. Selee tried to rebuild, but management balked at spending money for minor-league players, and Selee had no choice but to play his aging stars. The club suffered another blow when catcher Marty Bergen committed suicide in January 1900, and left the Beaneaters short behind the plate. After a fourth-place finish in 1900, several Boston stars jumped to the new American League and doomed the Beaneaters to a sixth-place finish in 1901. At season’s end, the Triumvirs hired Al Buckenberger to replace Selee.

Jim Hart, the man Selee replaced as manager of the Beaneaters in 1890, was the general manager of the National League Chicago Orphans and contacted Selee almost immediately after Selee’s firing hit the newspapers. In no time, Selee signed a contract to succeed Tom Loftus as manager of the Chicago ballclub.

Once again, Selee built a team by studying young players and finding places for them to fit in. Frank Chance, who joined the club in 1898, was a good-hitting catcher but struggled with his defense, especially his throwing. Selee put the better-fielding Johnny Kling behind the plate and transferred Chance to first base. Selee brought Bobby Lowe with him to Chicago, but Lowe relinquished the second base position to an intense young man from Troy, New York named Johnny Evers. During spring training, Selee looked at a dozen shortstops before giving the job to Joe Tinker. He had created the most famous double play combination of all time: Tinker to Evers to Chance.

Selee’s infusion of youth gave the Chicago ballclub the identity it needed. On May 27, 1902, the Chicago Daily News stated, “Frank Selee will devote his strongest efforts on the team work of the new Cubs, this year.” That sentence turned the Chicago Orphans into the Chicago Cubs, a name the team still carries more than 100 years later.

The Cubs improved to within one game of .500 in 1902 and jumped to 82-56 and a third-place finish in 1903. After that season, Selee pulled off one of his most daring trades, sending 20-game winner Jack Taylor to St. Louis for a young right-hander from Indiana named Mordecai Brown. They called him “Three-Finger” Brown because his pitching hand was severely injured in a childhood accident, but he could throw unusual curveballs, and Selee saw Brown as a future star. Selee, as usual, was correct; Brown soon became Chicago’s primary starting pitcher.

“To make a success,” Selee once wrote, “a baseball manager must enter into his work with every bit of energy he can command.”8 By the early 1900s, Selee’s poor health made him unable to apply his usual energy to the task of building another baseball team. He contracted a severe cold during the last series of the 1902 campaign, and by mid-October was diagnosed with pleurisy. He recovered, but his lungs remained weak, and he traveled to Colorado to spend the winter breathing the healthy mountain air. Selee spent the rest of his tenure with the Cubs battling health problems. In late 1904, he returned to Colorado to rejuvenate his weakening lungs.

The Cubs advanced to second place in 1904 and prepared to challenge for the league title in 1905, but Selee was not destined to be its leader. He fell ill during spring training at Santa Monica, California. He offered to give up the reins of the team, but Jim Hart convinced him to stay, so Selee opened the 1905 season as manager. His condition grew worse, and before long he developed both appendicitis and lung congestion. He stopped taking road trips, leaving Frank Chance in charge while he stayed in Chicago and sought medical attention. In July 1905, Selee received the bad news that he was suffering from tuberculosis; on July 28 he took a leave of absence. Frank Chance, who had been elected captain of the team earlier that season, succeeded him on an interim basis.9

Selee expected to return to the Cubs, but in the fall of 1905 Hart, who was ill himself, sold his interest in the Cubs to a group of Cincinnati and Chicago businessmen. Selee considered putting his own syndicate together to buy the team, but his health worsened again, and during the winter he severed his connection with the club. Chance became the full-time manager. Selee could only watch as Chance led the Cubs to three consecutive pennants and two World Series titles.

In late 1905, Selee moved to Denver, Colorado, hoping that the environment would restore his health. He could not stay away from the game, however, and in 1906 he bought an interest in the Pueblo team of the Western League. Despite his declining physical state, Selee managed the team for three seasons but never finished higher than fifth in an eight-team league. He sold the team after the 1908 campaign when his physical condition became precarious.

In 1909, he entered a sanitarium, the Rev. Frederick W. Oakes Home for Consumptives in Denver, where he died on July 5. He was 49 years old and left a widow, Mary, but no children. Frank’s parents, who were still living, brought his body back to Massachusetts, and buried him in the town cemetery in Melrose.

An updated version of this biography appeared in “The Glorious Beaneaters of the 1890s” (SABR, 2019), edited by Bob LeMoine and Bill Nowlin.

Notes

1 Sporting Life, September 23, 1893: 2.

2 Article by unknown writer, dated 1888, in Silent World, published by the Pennsylvania School for the Deaf.

3 Harold Kaese, The Boston Braves (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1948), 55-56.

4 Frank G. Selee, “Twenty-One Years in Baseball,” Baseball Magazine, December 1911: 55.

5 Kaese, 55.

6 Spalding’s Official Base Ball Guide, 1896. Reprinted in Dean A. Sullivan, ed., Extra Innings: A Documentary History of Baseball, 1825-1908 (Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 1995).

8 Selee, Baseball Magazine, December 1911: 56.

9 Chicago Tribune, July 29, 1905. The Tribune report made it clear that Chance was the interim, not the permanent, manager of the Cubs for the rest of the 1905 campaign.

Full Name

Frank Gibson Selee

Born

October 26, 1859 at Amherst, NH (USA)

Died

July 5, 1909 at Denver, CO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.