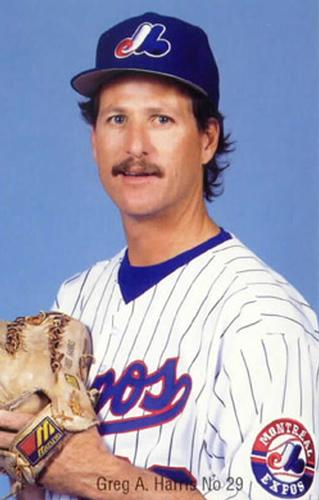

Greg A. Harris

The thing that sticks in the minds of many baseball fans about Greg Harris is that he was ambidextrous. Indeed, he had a glove custom-made for him with an extra thumb, so he could use it either on his left hand or his right hand. Though he long wanted the opportunity, there was only one major-league game in which he pitched left-handed.

The thing that sticks in the minds of many baseball fans about Greg Harris is that he was ambidextrous. Indeed, he had a glove custom-made for him with an extra thumb, so he could use it either on his left hand or his right hand. Though he long wanted the opportunity, there was only one major-league game in which he pitched left-handed.

Harris pitched 16 seasons in the big leagues, from 1981 to 1995. He worked for eight teams, though it was for the Boston Red Sox and Texas Rangers that he pitched the most. All told, he appeared in 703 games, starting 98 and closing in 266. He compiled a career 3.69 earned run average in 1,467 innings. Despite a good ERA, there was only one team for which he had a winning record. All told, his totals were 74-90, with 54 saves.

Greg Allen Harris was born on November 2, 1955, in Lynwood, California, a city in Los Angeles County north of Long Beach. He grew up in nearby Los Alamitos, also near Long Beach, with two younger brothers, Jeff and Brad, and a younger sister, Kelly. Their parents were Lester and Barbara Harris, both graduates of U.C. Santa Barbara.

Barbara Harris did odd jobs, working for a time at the local Broadway department store, but for the most part worked as a homemaker. Les Harris was a basketball and football coach at Long Beach’s Millikan High School. He was also the wood shop teacher. He later joined the faculty at Long Beach City Junior College and started teaching cabinet making. The college had vocational programs that taught students all it took to build housing — from roofing to refrigeration. Harris became the Dean of Occupation.

“We just had a normal growing up, which was pretty cool. We were all into sports,” recalled Greg Harris in a July 2021 interview.1 Both parents were avid golfers. As early as age 9 or 10, Greg was a ball boy for his father’s basketball and football teams. He was also the batboy for the baseball team.

One of Les Harris’s friends from college days at U.C. Santa Barbara was Bob Myers, the baseball coach at Millikan High School. “I was very lucky,” Greg said. “He kind of became my second dad. He’s the one who kind of put me on the right trail, mechanically and all that stuff. He’s a Hall of Fame coach from Long Beach, and he was assistant coach at Long Beach City when I got there, with the legendary Joe Hicks.”

Harris was drafted more than once but took his time before signing. A star at Los Alamitos High School — which through 2020 had 20 players selected in the draft2 — Harris was selected by the Angels in the 10th round of the June 1974 draft. His high school coach was a scout for the Angels. He didn’t sign. Nor did he sign when selected by the New York Mets in the fourth round of the January 1975 draft, by which time he was at Long Beach City College. A good friend of his father’s was Harry Minor, the head West Coast scout for the Mets. Minor came over to the house, and the three of them talked. “You’re not ready yet,” Minor told him.3

At Long Beach, Harris was an All-American, 18-4 with a 1.23 ERA4 He was drafted a third time, in the seventh round of the January 1976 draft, though once more he did not sign. Long Beach won the 1976 state championship. Harris went to Fairbanks, Alaska that summer and played for the Goldpanners, the only junior college player on a team stocked with Division I and Division II players.

The team traveled to Wichita, Kansas, for the annual National Baseball Congress tournament, and squared off against another Alaskan team, Anchorage, in the final championship game. Anchorage’s Dan Boone was locked in a pitcher’s duel against Harris, neither allowing a run for nine full innings. Boone had a one-hitter going but was reached for two runs in the 10th. Harris won the game, 2-0, firing a two-hit shutout.5 He won four games during the tournament and was named tourney MVP.

On September 17, 1976, he signed with the Mets as a free agent. Both the Red Sox and Mets had approached him. “They both offered me $20,000,” Harris said. The Red Sox had been doing well; the Mets had been struggling badly. He figured they were the ones who needed pitching the most.6 “Roger Jongewaard signed me,” Harris said, though Harry Minor had often come with him.

His first minor-league assignment came the next year. He pitched in the Double-A Texas League for the Jackson (Mississippi) Mets. Harris was 3-6 with a 5.42 ERA, starting in eight games and relieving in 22 games, working 83 innings.

Three more years of minor-league development followed. Harris pitched 187 innings in 1978, starting 21 games for the Single-A Carolina League’s Lynchburg Mets, with a 2.16 ERA, and working in six games for Jackson, with a 3.00 ERA. His entire 1979 season was with Jackson and his ERA improved to 2.26 over 25 starts; he was named to the league all-star team.7 After the season, he played in Mexico with Hermosillo. In 1980, he was advanced to Triple A and pitched in Norfolk, Virginia, for the Tidewater Tides. The teams he was with never enjoyed much success; he still had never had a winning record but his earned run average in 1980 was 2.70. He pitched for Ponce in Puerto Rican winter ball from 1980 through 1982.

In 1981, Harris made the major leagues. He got off to a good start in Tidewater, where he was 4-0 with a 2.06 ERA when he was called up to the Mets on May 18. His debut was on May 20, pitching for the Mets in San Francisco. He threw the first six innings of the game for manager Joe Torre, allowing just two runs in a 4-3, 10-inning Mets victory.

Five days later, he got his second start, a win against the visiting Philadelphia Phillies. He threw 5 2/3 innings, again allowing just two runs in a 13-3 victory. When he left the game, the Mets had a 10-2 lead. He lost two months of playing time during the season due to the players’ strike, finishing up with a 4.46 ERA and a record of 3-5, with 14 starts and two relief appearances.8

On February 10, 1982, Harris was one of three players traded to the Cincinnati Reds for five-time All-Star outfielder George Foster. He started the season in Triple A again, this time with the Indianapolis Indians, and was 4-1 in the early going. Called up to the majors, he won his first start on May 25, and his second, but lost the next two. The Reds began to use him as a reliever, usually in the middle innings. He did get four more starts near the end of the season, but finished with a 2-6 record for the last-place Reds, with a 4.83 ERA in 34 games.9

Harris spent almost all of 1983 with Indianapolis, working mostly as a starter, going 9-12 with a 4.14 ERA. He pitched in just one big-league game — one inning of relief on May 14 against visiting San Francisco, in which he was tagged for three earned runs.

The Montreal Expos selected Harris off waivers in late September and he opened the 1984 season for the Expos. He worked in 15 games, all in relief, during April and May. He was 0-1 but had an excellent 2.04 ERA. Even so, he was outrighted to Indianapolis, an Expos affiliate in 1984, and was there almost two months, going 4-4 with a 4.43 ERA. On July 20, as the San Diego Padres headed into a stretch of seven doubleheaders, they traded infield prospect Al Newman to acquire Harris.10 He worked in 19 games for the Padres, sticking with the team the rest of the season (2-1, 2.70).

Harris also got his first taste of postseason play in 1984. In Game One of the NLCS, the Chicago Cubs built a 5-0 lead off starter Eric Show. Harris was brought in to pitch the fifth. He gave up six runs that inning, and two more the next — left in despite being ineffective, to keep the rest of the staff rested for the next games.11 It was also the Padres’ first time in the postseason. They won the final three games of the best-of-five series and advanced to the World Series against the Detroit Tigers.

The two teams traded wins in Games One and Two. Detroit built a 3-0 lead in Game Three off Tim Lollar, who then loaded the bases in the third inning. Greg Booker came in to relieve Lollar and walked in a fourth run before securing the third out. The Padres scored once. In the third, Booker got two outs but walked the bases loaded. Harris was summoned — but hit the first batter, Kirk Gibson, forcing in a fifth run. He got the final out and then worked the remaining five innings, without allowing a run and just three scattered hits. The Tigers won the game, though — and, the following day, the Series.

As spring training was about to get underway, the Texas Rangers purchased Harris’s contract in February 1985. The Rangers were his fourth major-league team, the first in the American League. He became the team’s most frequently used reliever, closing 35 of the 58 games in which he appeared. He was 5-4, 2.47 for the season. He struck out 111 batters in 113 innings.

Harris pitched for the Rangers again in 1986. That year, Texas Rangers climbed from seventh place to second place in the American League West. By June 10, Harris had already posted 11 saves, matching his career high. He finished with 20 saves. In 73 games — in 63 of them, he finished the game — he was 10-8, 2.83 for manager Bobby Valentine. Harris had thought he was going to have his first opportunity to pitch with both hands in 1986, and Mizuno even made the special ambidextrous glove for him. However, with the Rangers somewhat unexpectedly in contention,12 Valentine didn’t want to take the chance.

After the season, Harris played in Japan, touring with a team of National League stars.

Texas dropped to sixth place in 1987, though, and Harris’s record fell to 5-10 (4.86 ERA). He was used more in long relief, averaging more than three innings per appearance. Dale Mohorcic had been given the role of closer. Harris struggled badly early on. On May 10, the Los Angeles Times observed he had “been in six games with a lead or tie and blown them all.” He was quoted: “I’m a walking time bomb.”13

Harris never really did snap out of whatever funk he was in, though from June 5 on, he was primarily a starter and had a few good games. Having to make that adjustment too, though, was not helpful in regaining the success he’d had the prior year. It was a tough year in the field as well. His five errors tied the club record for errors by a pitcher — he then went error-free over the last two months.

One bizarre story about Harris came near the end of the season. He missed some games with tightness in his forearm; one diagnosis was “sunflower seed elbow” caused by repeatedly flicking sunflower seeds toward a friend seated in the stands.14

The Rangers released Harris four days before Christmas in 1987. The Cleveland Indians signed him as a free agent for 1988, but they let him go near the end of spring training despite a sub-2.00 ERA that spring. Seeing Harris available, the Philadelphia Phillies signed him to bolster their roster. Starting out with the Maine Phillies, he was in three games before being brought back to the majors. Once there, he pitched 107 innings in 66 appearances, with a 4-6 won/loss record despite an excellent 2.36 ERA. Well into the season, Phils pitching coach Claude Osteen said, of both the Rangers and Indians, “The only reason I can see for [them] not wanting him would be that they had only one specific role to fill and he wasn’t the guy.”15 The Phillies finished last in the NL East.

Harris became a free agent after the 1988 season but signed again with the Phillies a month later, in December.

During 1988 and 1989, there was a stretch when there were two pitchers named Greg Harris in the National League. The other was Gregory Wade Harris, a right-hander from North Carolina who pitched in the majors from 1988 to 1995. The two met just once: on May 20, 1989, at Veterans Stadium in Philadelphia. San Diego had a 3-1 lead in the bottom of the sixth, when they brought in G. W. Harris to relieve. One inherited run scored. The Phillies had pinch-hit for their starter and had G. A. Harris start the seventh. He worked a scoreless seventh and eighth, the final batter he faced being San Diego’s Harris, who grounded out. The game ended, 3-2, with neither Harris giving up a run. Greg W. Harris got a save.

Greg A. Harris appeared in 44 games during the first four months of the 1989 season for the Phillies, with a 2-2 record and an ERA that jumped from 3.22 to 3.58 during his final game on July 31. At one point, 10 of the 13 baserunners he had inherited came around to score.16 The Phillies were 42-62 and in sixth place. The team released Harris outright. Manager Nick Leyva simply said that the team needed to “find out about our young people.”17

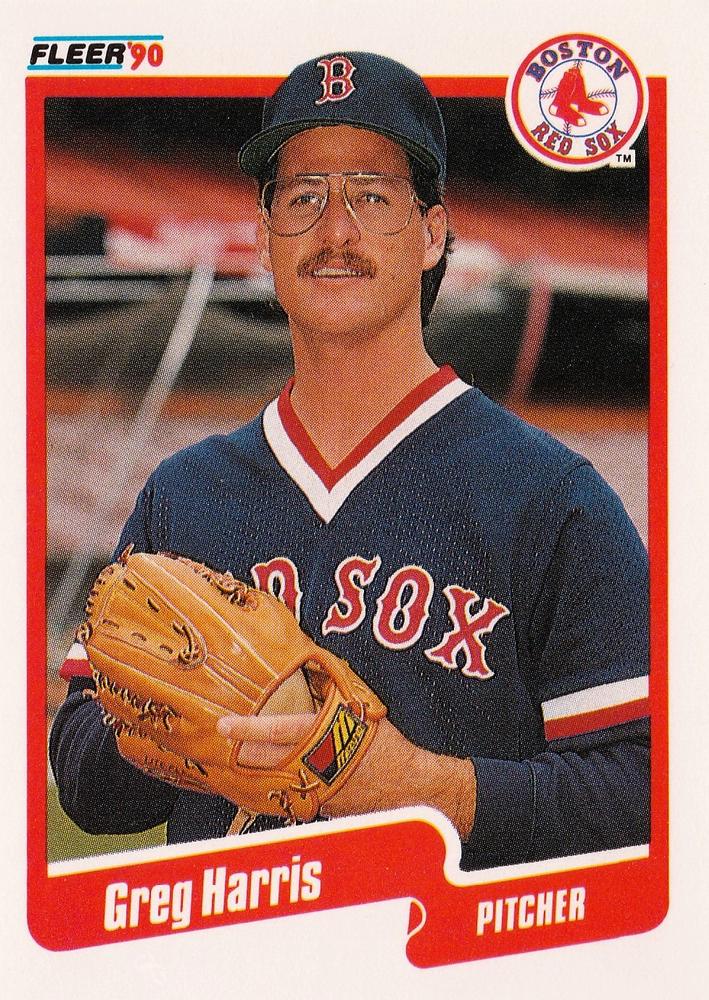

Harris made his way back to the American League. The Boston Red Sox needed to bolster a pitching staff beset with injuries; on August 7, 1989, they selected Harris off waivers.18 He was with the Red Sox from then until late June 1994, the longest stretch he spent with any one team. In the 15 games he worked for Boston in 1989, primarily as a middle reliever, he was 2-2, 2.57. He liked the area enough that he built a house in Centerville, on Cape Cod, and became a year-round resident for close to a decade.

Harris re-signed with the Red Sox as a free agent in February 1990. He had only relieved for Boston in 1989 — but in 1990, still working under manager Joe Morgan, he started 30 of the 34 games in which he appeared. He drew the admiration of several Bostonians for taking public transportation — the Green Line trolley — to work at Fenway Park.19

The 1990 Red Sox finished first in the AL East. Harris compiled an even 4.00 ERA, and his 13-9 record placed him third on the team in wins behind Roger Clemens (21-6) and Mike Boddicker (17-8). His ERA had been 3.17 at the end of August but rose significantly over his final six starts. The 184 1/3 innings he pitched were more than 40 above his prior high and almost double his workload from the previous year.

The 1990 Red Sox finished first in the AL East. Harris compiled an even 4.00 ERA, and his 13-9 record placed him third on the team in wins behind Roger Clemens (21-6) and Mike Boddicker (17-8). His ERA had been 3.17 at the end of August but rose significantly over his final six starts. The 184 1/3 innings he pitched were more than 40 above his prior high and almost double his workload from the previous year.

The Red Sox were swept in the American League Championship Series, four games to none, by the Oakland Athletics. In relief of Dana Kiecker, Harris faced four batters in Game Two. Mike Gallego’s leadoff single in the top of the seventh proved to be the eventual winning run in the 4-1 A’s victory. Gallego scored on a Harold Baines groundout off Larry Andersen, who relieved Harris.

In April 1991, Morgan said he foresaw Harris as his #2 starter after only Clemens.20 Harris was in and out of the starting role a couple of times, spending the last two months as the setup man in the bullpen after Jeff Gray was injured. He hit double digits in wins again in 1991. He finished 11-12, 3.85 after a 1-5 start through May. Clemens won 18 games and Joe Hesketh won 12.

Harris returned to the bullpen in 1992. He appeared in a team-high 70 games, with only two of them starts. His ERA improved considerably, to 2.51 (he had been under 2.00 through July) — more than a run below the team’s 3.58. The Red Sox, though, finished last in the division.

In 1993, his 80 appearances led the league. Not until his 23rd appearance of the season did he allow an inherited runner to score. The Red Sox finished fifth (80-82). Harris’s record was 6-7 with a 3.77 ERA. He was 37 years old. At that point in team history, he was the only pitcher to have appeared in 70 games for two years in a row.21

During the 1994 season, Harris pitched in 35 games over the first three months of the season, but after a 3.57 ERA in April, he hit a rough patch. His ERA climbed to 6.83 by the end of May and to 8.28 when the Red Sox released him on June 27. Because of incentives in his contract, it would automatically renew when he reached a threshold number of “points.” He was leading the American League in appearances as spring turned to summer, but getting hit hard enough that the team could reasonably let him go without triggering a grievance.22 Harris was angry at being released, and placed the blame on Red Sox GM Dan Duquette.23

Less than a week later, he was signed by the New York Yankees. He appeared in three games — on July 4, 5, and 9, but was released on July 13 having pitched only five innings. He had one decision, a loss, which brought his overall record to 3-5. He had the rest of the year off, so went home and made sure to keep in shape, while still drawing salary.

The season ended prematurely, due to the strike that year which resulted in the World Series being canceled. Harris joined many who went to the Dominican Republic for winter ball. He pitched well there, and right at the end of spring training in 1995, he signed with Montreal.

Harris joined the Expos two months later, after going 3-0 (1.06) in 11 games with the Triple-A Ottawa Lynx. In his second stint with the Expos, he worked in 45 games with an ERA of 2.61 and a 2-3 record. It was his final season.

It was in his penultimate game — September 28, 1995 — that Expos manager Felipe Alou finally gave Harris the opportunity to get his name into the record books by pitching to two batters as a left-hander. It was a Thursday night home game at Stade Olympique against Cincinnati. After eight innings, the Reds were leading, 9-3. Montreal starter Pedro Martinez had been knocked out after six innings.

At the plate, Harris had been a switch-hitter throughout his career. Batting left-handed, he was 10-for-52 (.192) and batting right-handed he was 5-for-16 (.313). His overall career batting average was .221.

But, although he had ample opportunities to swing from either side of the plate, he had exclusively been a right-handed pitcher. That was about to change. The date he had been waiting for came on September 28, 1995.

Harris had talked with the Wall Street Journal a couple of months earlier. Discussing baseball fantasies, he said: “In my imagination, mine goes like this…I come into a game as usual, to get a right-handed batter out, and I do. A left-handed hitter is next, and the manager leaves me in. I switch my glove to my right hand and prepare to pitch to him lefty. His mouth drops. While he’s gaping, I whiff him on three pitches.”24 He had pitched batting practice left-handed a few times, and always had his custom glove made by Mizuno. It was the glove Harris always used; Mizuno provided him with two new ones each year.25

Harris had wanted to pitch as a left-hander for so long that when the moment came, he admitted that he “had jelly knees.”26 Alou told him he had to pitch righty to the first batter, Reggie Sanders. The right-handed hitter grounded out, short to first. “All I was thinking was to get Sanders out. When he grounded out to short, I took the ball and thought, ‘Here we go.’ I think my heart stopped.”27 Using his special six-fingered glove, he pitched left-handed for the first time in the majors. The last time there had been an ambidextrous pitcher was in 1888 when the Louisville Colonels’ Elton “Ice Box” Chamberlain pitched in the American Association.28

The first batter Harris faced as a southpaw was first baseman Hal Morris, a left-handed hitter. His first pitch sailed outside, past Montreal catcher Joe Siddall, and Morris walked after three more balls in a row. Next up was catcher Eddie Taubensee, also a lefty swinger. Harris got a strike — and a standing ovation from an energized crowd of 14,581. Siddall fielded Taubensee’s high chopper in front of the plate and threw him out at first. Morris went to second base. Righty-hitting second baseman Bret Boone was up next; Harris switched back to pitching righty. He retired Boone on a weak grounder he fielded himself, throwing to first right-handed, of course.29 Inning over. Harris was replaced by pinch-hitter Shane Andrews.

After the game, Harris said, “I’m still in shock.”30 He said, “It was probably the most nervous time of my life. I realized this was happening and this was the opportunity I was waiting for. The fans were crazy because they saw me warm up left-handed in the bullpen…Thank goodness Morris wasn’t a right-handed hitter or he probably would have ended up in the hospital. The most fortunate thing was I was able to face another lefty (Taubensee) and actually got somebody out.” He added, “I didn’t hit anybody. I didn’t hurt anybody, and it didn’t ruin the integrity of the game. It came out very professional and that was the way I wanted it, to prove that it was not a joke, that it was something I could do.”31

The glove was donated to the National Baseball Hall of Fame.32 It was nearly 20 years before another switch-pitcher — Pat Venditte of the Oakland A’s — appeared in the majors. As a young boy, Venditte idolized Harris.33

Harris’s final game in the majors was the very next day. He pitched two innings of scoreless ball, allowing just one hit.

Harris turned 40 after the 1995 season ended. He was then the oldest pitcher in the National League. At the time, many teams were intent on a “youth movement.” As Harris reflected in 2021, “Us veterans who still had plenty of life left were let go or unable to re-sign. Look how that has reversed. Veterans are playing longer and the youth movement did not quite work out. The way they use the relievers now, I could still be pitching.”34

For the next three years, Harris worked in the Tampa Bay system. “Tom Foley became the minor-league coordinator. We played together in Cincinnati. We worked and put the minor-league system together for the inaugural year in 1998. I worked as pitching coach for the Hudson Valley Renegades for two years. Tom coached in Billings. After the second year, we got Charleston, South Carolina. Each year, we added a club, and eventually ended up in Durham. I ended up coaching in St. Pete in my third year in the Florida State League.” In the fall of 1998, he was the pitching coach for the East Coast team in the Arizona Fall League.

In 1999, he worked for the Seattle Mariners as pitching coach with the California League’s Lancaster Jethawks. This offered the opportunity to work and commute from home. Around the turn of the century, more computerization was coming into pro ball, so he turned to other work, coaching at area colleges — for instance, a stretch at Cypress Junior College (2008-2011) — and even at his high school. Helping some old friends, he put in time working with younger players. He worked as assistant coach at Kennedy High School of La Palma, California, from 2001-06, and was active with both Connie Mack and Mickey Mantle Junior Olympic baseball from 2002-05. For 12 years (2000-2011), he started and ran Strike Zone Pitching School to teach throwing and pitching mechanics for players aged 7 through college.

Harris’s first marriage, in September 1977 to Joni Lynn Kinne, produced two daughters named Shannon and Lindzy. He also had a son — Greg Allen Lester Harris, whom he raised — from his second marriage to Liz Ohman. One of the reasons he elected to stay closer to home was to spend more time with his son.

Harris aspired to become a big-league pitching coach after his playing days. He was learning the ropes in his player development work with Tampa Bay and then with Hudson Valley and Lancaster. As he himself grew up, his father had come to every single one of his games. Harris explained that after the ’99 season, “I made a choice to raise my 8-year-old son. I chose to do private lessons and coach locally to be around my son until he graduated high school. Then I would go back and pursue the role as a big-league pitching coach.”

To his surprise, Harris found that nine years away from pro ball had brought drastic changes. “Teams were hiring ex-minor leaguers who never pitched a day in the big leagues as pitching coaches just to make sure the staff had their throwing routine, and to file reports on each pitcher,” Harris said. “All the development work was done by pitching coordinators, not by that team’s pitching coach.”35 Once again, something of a youth movement had come into play.

Eventually, it came time to retire. Then kismet called. He reconnected with his high school sweetheart, the former Kelly Helseth. “We got reunited 32 years later,” Harris said. “It’s pretty awesome. We dated when she was a freshman and I was a junior in high school. It’s a great story. It all comes around. We probably should have stayed together back then. She was set designer for Days of Our Lives, and also an executive administrator in the music industry. She’s an architectural designer, a full-service master project manager, a ground-up construction designer and builder.”

Harris has had both knees replaced, owing to the wear and tear from playing. At the time of the July 2021 interview, he was following the career of son Greg, a right-handed pitcher who was playing with the Winnipeg Goldeyes in the American Association of Professional Baseball, an independent league. Drafted by the Dodgers in 2013, he joined the Rays organization in 2015. He bounced back after suffering a labrum tear in 2018 but then had to endure a year off in 2020 when minor-league baseball was canceled during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The elder Greg Harris and Kelly are both retired now, living on Canyon Lake about an hour from where they both grew up. As of late 2021, he is writing a book, with the working title Ambidextrously Speaking.

Last revised: October 20, 2021

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Kevin Lamp and Greg’s wife Kelly Ford Harris for assistance.

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and David Bilmes and fact-checked by Evan Katz.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, and SABR.org.

Notes

1 Author interview with Greg Harris on July 28, 2021. Unless otherwise indicated, all direct quotations from Greg Harris come from this interview.

2 https://www.baseball-reference.com/draft/?key_school=e6020635&exact=1&query_type=key_school

3 Author interview with Greg Harris.

4 Kurt Rosenberg, “This Time, Tag Greg Harris’ Bag ‘San Diego’,” New York Times, July 25, 1984: III, 6.

5 “Goldpanners claim national title,” Fairbanks Daily News-Miner, August 25, 1976: 1. See also “Panners beat Pilots for national title,” Fairbanks Daily News-Miner, August 25, 1976: 15. It was the fourth national title for Fairbanks over a five- year stretch.

6 Timing can be everything. In his 2021 interview, Harris said, “‘78, I played in Lynchburg, Virginia. Winston-Salem was the Red Sox minor-league…when I played against them, I go “Holy crap! They don’t have any pitching.” As it turned out, the Red Sox didn’t have any minor-league pitching, but they had offense. If I’d have picked the Red Sox, I probably would have made it to the big leagues sooner.”

7 “El Paso’s Brouhard Wins Triple Crown,” The Sporting News, September 22, 1979: 39.

8 During the strike, he and pitcher Mike Scott worked out at Long Island’s Port Washington High School. See Gordon S. White, Jr., “Workouts in Strike Paying Off for Scott,” New York Times, August 7, 1981: A17.

9 The Mets finished last in their division, as well. Foster had a disappointing season.

10 See Rosenberg for detail on some of Harris’s background and his arrival with the Padres.

11 Sportswriter Bill Conlin even wrote, “Many people feel that Harris was a real unsung hero in that Wrigley Field holocaust, staying out there through a merciless beating so Williams could rest Andy Hawkins, Dave Dravecky, Craig Lefferts and Rich Gossage.” Bill Conlin, “Tigers Sleepwalk over Padres,” Philadelphia Daily News, October 13, 1984: 44.

12 Harris had talked to a representative from Mizuno, a company that had introduced several innovations — “they were known as the gimmick company,” he says — and when he arrived at spring training in 1986, there were three custom-made gloves for him. “It was a great glove. Number one, you could open it farther than a regular glove. And it was legal. In my locker was a set of rules. Bobby Brown became the president of the American League that year. I’ve got the letter that he wrote, that he gave to all the major-league umpires. This is back in 1986, anticipating what might happen.”

13 Ross Newhan, “Baseball A New Red Machine?,” Los Angeles Times, May 10, 1987: 10.

14 “Sunflower seed elbow!,” The Sporting News, September 7, 1987: 22.

15 “Phillies,” The Sporting News, August 22, 1988: 15.

16 There was one amusing note during the June 15 game against the Pirates. Pittsburgh’s Andy Van Slyke noticed the unusual glove that Harris wore. Phillies third baseman Randy Ready accidentally misspoke, saying, “Because he’s amphibious.” Van Slyke asked, “Does that mean he can throw underwater?” See “‘Amphibious’ Right, er, Lefty,” The Sporting News, July 3, 1989: 16.

17 “Phillies,” The Sporting News, August 14, 1989: 23.

18 The Red Sox could have saved a considerable amount of money by waiting for Harris to clear waivers, but GM Lou Gorman said he was afraid another team would claim him. Steve Fainaru, “Harris to lend a hand,” Boston Globe, August 8, 1989: 58.

19 When he first came to Boston, he lived in a condo near Cleveland Circle. “That’s where I stayed. I’d either walk — which was 45 minutes or take the T. They drop you near Fenway. I thought that was great. There are really a lot of characters on a Sunday morning.” He didn’t take the streetcar in his uniform. “Nobody knew who I was. I was incognito and that was how I liked it.”

20 Joe Giuliotti, “Boston Red Sox,” The Sporting News, April 8, 1991: 22.

21 Bill Ballou, “Team throws Harris curve,” Worcester Telegram and Gazette, June 28, 1994: D1.

22 Nick Cafardo, “Red Sox throw Harris a curve: He’s released,” Boston Globe, June 28, 1994: 65.

23 Sean Horgan, “Harris releases his frustration,” Hartford Courant, July 5, 1994: D5.

24 Frederick C. Klein, “‘Six-Finger’ Harris dreams of making historic switch,” Wall Street Journal, August 11, 1995: B10. The Journal article explained:

A couple of more-recent major league pitchers have had the capacity to throw with either hand. One was Dave “Boo” Ferriss of the 1940s Boston Red Sox. Another was Calvin Coolidge Julius Caesar Tuskahoma “Buster” McLish, who pitched for several teams in a 15-season career that ended in 1964.

The right-handed Mr. McLish did throw lefty to one batter in a Venezuelan Winter League game but got off just one delivery. “The other team’s manager came out and argued about it with the umpire for 15 minutes,” he later said. “I thought, `Hell, it’s not worth it,’ and went back to regular.”

In fact, the rules on switch pitching (and hitting) are simple: Once a pitcher (or hitter) begins to face a batter (or pitcher) from one side, he must complete that turn the same way. “In that respect, there’s nothing to it but to do it,” Mr. Harris avers.

25 Bill Francis, “‘Switch-pitcher’ gives glove to HOF,” Freeman’s Journal (Oneonta, New York), October 15, 1995.

26 Associated Press, “Harris throws a rare right-left combo,” Los Angeles Times, September 29, 1995: C7.

27 “Harris throws a rare right-left combo.”

28 Charles F. Faber wrote Chamberlain’s biography for SABR, explaining that he was “one of three 19th century hurlers known to have pitched ambidextrously. (The others were Larry Corcoran and Tony Mullane.) It would be a bit of a stretch to call Chamberlain ambidextrous. But he did pitch four innings left-handed in the minors and on May 9, 1888, he pitched the first seven innings right-handed and the final two innings as a lefty as the Colonels routed the Kansas City Cowboys 18-6. He seldom pitched left-handed, but he used his dexterity another way. He did not wear a glove, so he could use either hand to throw to a base. As baserunners could never tell with which hand he would throw, he became adept at picking them off.” Charles F. Faber, “Ice Box Chamberlain,” SABR BioProject, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/ice-box-chamberlain. There is the possibility that Bert Campaneris threw ambidextrously during a game on September 9, 1965 in which, as a stunt, he played all nine innings during the course of one game.

29 Harris’s performance is available on YouTube, allowing viewers to see the event — and him changing the custom glove from one hand to the other. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s4ozn8kaTTU

30 “Harris throws a rare right-left combo.” As far back as 1985, it had been reported that Harris was working on his left-handed delivery with Texas Rangers pitching coach Tom House. See Peter Gammons, “A. L. Oscars for Mattingly, Saberhagen,” The Sporting News, October 14, 1985: 28. Harris later said that in 1986, “I had worked on it every other day for three months.” Ken Davis, “Being a ‘switch pitcher’ all that’s left for Harris,” Hartford Courant, August 9, 1989: F5A. Red Sox manager Joe Morgan said he might try him out left-handed. “In September, in a blowout, why not?” said Morgan. But he never did. See “A.L. Insider,” USA Today, August 9, 1989: 04C.

31 Francis, “‘Switch-pitcher’ gives glove to HOF.”

32 Francis, “‘Switch-pitcher’ gives glove to HOF.”

33 John Hickey, “A’s call up switch-pitcher Pat Venditte,” Times-Herald (Vallejo, California), June 5, 2015.

34 Email from Greg Harris, August 3, 2021.

35 Email from Greg Harris, August 3, 2021.

Full Name

Greg Allen Harris

Born

November 2, 1955 at Lynwood, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.