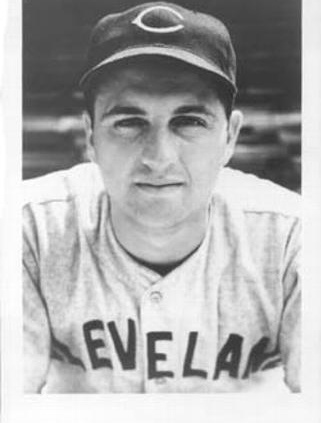

Harry Eisenstat

Harry Eisenstat might have said it best after the conclusion of his eight-year (1935-1942) big-league career: “As long as baseball fans talk about Bob Feller, my name will probably never be forgotten.”

Harry Eisenstat might have said it best after the conclusion of his eight-year (1935-1942) big-league career: “As long as baseball fans talk about Bob Feller, my name will probably never be forgotten.”

When Feller set the modern big-league record (at the time) with 18 strikeouts in a nine-inning game in 1938, Eisenstat – in his most famous moment – outdueled the future Hall of Famer.

Pitching primarily out of the bullpen when relief pitching was less central to the game, Eisenstat packed a lot of life into his professional baseball career before it, like many others, was curtailed by World War II. One of the infrequent Jewish players in baseball,2 the lefty debuted with his hometown Brooklyn Dodgers only one year after his high school graduation. He later became a teammate and lifelong friend of the most famous Jewish ballplayer of the era, Hank Greenberg. Eisenstat once recorded victories in both ends of a doubleheader in which Greenberg homered in each game.

Harry Eisenstat was born in Brooklyn, New York, on October 10, 1915. He was the youngest of three children born to Samuel and Anna (Greenberg) Eisenstat, Jewish immigrants from Russia. Samuel, a carpenter and builder, was born in 1884 in Minsk (which became the capital of Belarus after the Russian Revolution). Anna, a homemaker, was born in 1883 in Kiev (now the capital of Ukraine). Both emigrated in 1906. Their first child, Bertha, was born in 1910, followed by Max in 1912, and Harry.

Harry grew up in Brooklyn’s Flatbush neighborhood and starred on the James Madison High School baseball team, initially as a first baseman. He transitioned to the mound as a sophomore in 1932 and made his pitching debut after another hurler developed a sore arm. Eisenstat was a terrific replacement and thereafter became Madison’s star pitcher.3 The Brooklyn Times Union described him as “short and stocky” with “a wide, sweeping curve which was plenty puzzling.”4 Just three years later, Eisenstat was toeing a major-league rubber for the Brooklyn Dodgers.

From his first amateur season, Eisenstat displayed the control that was a characteristic attribute of his professional career.5 He was entrusted to start Madison’s 1932 city championship match at Yankee Stadium in front of 20,000 schoolchildren, but lost, 2-1.6 He was named to the post-season All-Brooklyn Scholastic All-Star team.7

Eisenstat’s junior year was highlighted by his perfect game against Abraham Lincoln High School in May 1933.8 After the season, he was again named to the Times Union’s P.S.A.L. All-Scholastic Nine.9

In 1934, James Madison’s ballclub took a step backward as their ace “suffered continually from colds and other ailments.” But Eisenstat still made second-team postseason Times Union All-Scholastic All-Star team.10

Upon Eisenstat’s graduation that year, his father had plans for him as a clothing salesman, but first he had to try his luck at professional baseball. The Dodgers had been paying attention to him since his 1933 perfect game, so when the 1934 school year ended, first-year Brooklyn manager Casey Stengel enlisted Eisenstat to pitch batting practice to the big-league club. In August, Eisenstat took the mound for the Dodgers in an exhibition against their Class C Dayton (Ohio) Ducks affiliate and won, 6-3. “He’s a nice-looking southpaw, all right,” Stengel said after the game. “He needs experience. He’s got swell control for a left-hander already.”11 (Eisenstat’s Brooklyn debut, while not reflected in his career statistics, came back to bite the Dodgers after the 1937 season when he was declared a free agent.) Eisenstat accompanied the Dodgers to Cincinnati to continue pitching batting practice before reporting to the Ducks to finish the 1934 season. He registered three wins in six appearances for Dayton.12

In spring training 1935, Eisenstat made the Dodgers at age 19 with standout pitching in the Grapefruit League, including five scoreless innings against the American League champion Detroit Tigers.13

His first major-league appearance came at Forbes Field in Pittsburgh, on May 19, 1935. Coming on in relief of future Hall of Famer Dazzy Vance in a tie game in the sixth inning with two runners on, Eisenstat recorded his first out when Brooklyn catcher Al Lopez picked Tom Padden off second base. The Pirates’ Woody Jensen then singled before Eisenstat struck out Paul Waner to end the threat. The Dodgers rallied to take the lead, but Eisenstat was charged with the loss after he allowed four runs in the eighth. Three of the first five batters he faced were future Hall of Famers: Waner, Arky Vaughan and Pie Traynor.

Eisenstat made his second and final big-league appearance of 1935 in Chicago on Sunday, May 26. Entering in the seventh inning, he allowed three runs (two earned) in the final two innings of an 8-3 loss.

Following a demotion to Dayton, Eisenstat shined, winning 18 games against 8 losses with a 2.73 ERA. After losing his first five decisions, he won six of his next nine decisions and concluded the regular season with 12 straight wins. In the post-season playoffs (which Dayton lost in six games), he tacked on a win before losing his final two decisions of 1935. He finished 1935 with 41 consecutive scoreless innings and tacked on 10 innings in the first playoff game without giving up an earned run.14

Eisenstat worked in retail in Brooklyn during the offseason and put on some weight (likely to his listed size of 5-foot-11, 185 pounds). He sought to pair his impressive control and curveball with a more convincing fastball, a recurring theme throughout his career. “I learned a lot about pitching last year and this time I think I’m prepared to remain with the team,” he said that winter. “I have put on about ten pounds in the last year and think this extra weight will enable me to get more speed on my pitches. I’m not worried about my curve and my change of pace.”15

Eisenstat suffered a sore arm in spring training 1936 and was sent to the minors for a third time. With the Allentown (Pennsylvania) Brooks in the Class A New York-Pennsylvania League, he led the team with 19 victories with a 3.57 ERA before making his return to the Dodgers in September.

The hometown boy made his first major league start at Ebbets Field on September 12, 1936, against the second-place Cardinals and their ace Dizzy Dean, whose won-loss record coming into the game was 22-11 in his final dominant season for St. Louis. Eisenstat trailed 2-0 entering the fifth inning before Brooklyn shortstop Lonny Frey’s two-out error opened the flood gates, and six unearned runs crossed the plate.16

Eisenstat made his second start in the second game of a September 24 twin bill against the last place Philadelphia Phillies. He excelled, earning his first big league victory in a darkness-shortened, seven-inning complete game, permitting two runs (one earned) on seven hits while also collecting his first hit and walk at the plate. In all, he pitched 14 1/3 innings for the Dodgers in 1936, allowing 17 runs, of which only nine were earned.

“They seem to think my fastball hasn’t enough zip on it to get me by in the big leagues,” Eisenstat said after the season. “But I believe this to be bunk and will prove it before another season is over…I’ll be a regular in Brooklyn next summer.”17 The Dodgers fired Stengel after finishing in seventh place with a 67-87 record and brought another future Hall of Famer to manage the club, former Brooklyn pitcher Burleigh Grimes.

Eisenstat opened the 1937 season with the Dodgers as a reliever and spot starter and went 3-0 with a 1.59 ERA in his first six appearances. Grimes gave him three starts in the second half of May, but the Dodgers lost all of them. After three relief outings, Eisenstat made his final appearance for Brooklyn on June 10. Facing the Cubs, he was knocked out in the second inning and suffered his third loss.

Two days later, the Dodgers purchased 37-year-old Waite Hoyt from the Pirates. Hoyt – a fellow Brooklyn native who had attended James Madison’s rival Erasmus Hall High School – claimed Eisenstat’s role, making 19 starts for the Dodgers in his last full season. Meanwhile, Eisenstat was sent to the Louisville (Kentucky) Colonels of the Class AA American Association, where he went 8-9 in 25 games (17 starts) with a 3.83 ERA. It was his last trip to the minors, and he continued to prove himself a fine hitter for a pitcher, batting .273 with a triple in 55 at-bats. (He had hit .283 in Allentown the prior summer, with two doubles and two triples in 120 at-bats.)

Eisenstat wouldn’t pitch for Brooklyn again, though. He was declared a free agent by Commissioner Kennesaw Mountain Landis after the 1937 season because he had been optioned to the minor leagues four times, including in 1934 when he had only been in the organization for a few weeks and did not appear in a game for the Dodgers. Free to sign with any team, Eisenstat was recruited by none other than Detroit Tigers slugger Hank Greenberg, his friend and the most famous Jewish athlete in America. The Tigers had finished a distant second behind the New York Yankees the previous season and had only one left-hander of note on their roster, Jake Wade, who had gone 7-10 with a 5.39 ERA.

Eisenstat pitched only four times out of Detroit manager Mickey Cochrane’s bullpen in the first month of the 1938 season before he suffered a fracture over his right eye during batting practice that knocked him out of action for several weeks.18

He won his first game back with four shutout innings of relief and then made his first start of the season, against the Washington Senators at Briggs Stadium on June 18. Eisenstat pitched the second complete game of his career, allowing three runs (two earned) to earn the victory. He shuffled between the rotation and bullpen for the rest of the season, completing four of his eight starting opportunities between June and early September.

On July 30, the Philadelphia Athletics came to Briggs Stadium for a doubleheader. Though Eisenstat did not start either game, he won both ends of the twin bill in relief while Greenberg homered in the eighth inning of each contest. In the first game, Eisenstat came on in the top of the eighth, just in time for Detroit’s winning five-run rally in the bottom of the inning. In game two, Tiger starter Boots Poffenberger again spotted Philadelphia a big lead before Detroit rallied for eight unanswered runs and an 8-7 victory. Eisenstat pitched the final four innings without allowing a run for his second victory of the day. (Greenberg’s two home runs gave him 37 in 92 games, a pace of 62 for a 154-game schedule.)

After Eisenstat’s complete game loss to Cleveland on September 6, he pitched in relief the rest of the month before he started game one of a doubleheader on the season’s final day. It would be the game that Eisenstat was asked to talk about for the rest of his life.

Greenberg entered that final day of 1938 with 58 homers, two shy of the record 60 hit by Babe Ruth in 1927. He had homered three times in Cleveland in 1938, but all of them came at hitter-friendly League Park. The finale would be played at spacious Cleveland Stadium. As it happened, he didn’t make it to 60 homers (going 1-for-4 with a double, walk and two strikeouts in the opener and 3-for-3 with a walk in a seven-inning darkness-shortened season finale) but it proved to be a historic day, nevertheless.

Cleveland pitched phenom Bob Feller in the opener. In his unprecedented first start two years prior, the then-17-year-old had struck out 15 batters. Four starts later, he tied Dizzy Dean’s modern record of 17 strikeouts in a nine-inning game.

Feller fanned the leadoff batter, Benny McCoy, then recorded every out in the second, third, and fourth inning via the strikeout (while allowing two singles and a walk). He recorded the first two outs of the fifth on strikeouts as well, making it 11 outs in a row via the K. Meanwhile, Eisenstat had put a man on in each of the first five innings via a hit or walk, but he kept the game locked at zero. Detroit scored twice in the sixth and two more runs in the eighth while Eisenstat retired 11 batters in succession. Feller finished off Detroit in the top of the ninth with his record-setting 18th strikeout, but Eisenstat carried a 4-0 lead into the bottom of the frame. An error, two Cleveland singles and a sacrifice fly ruined his shutout, but – while Feller established the new single-game strikeout mark – Eisenstat prevailed, 4-1.

“Feller was throwing the ball at about 105 miles per hour and with a curve at about 95 miles per hour,” Tigers catcher Birdie Tebbetts remarked later. “He just mowed us down. Yet we were able to score off of him. Meanwhile, Eisenstat was throwing the ball at about 81 miles an hour and struck out three guys. And he beat Feller. It was kind of funny.”19

Eisenstat would dine out on the story for years, becoming a significant footnote to baseball lore: “Do you know who beat Feller when he set the record with eighteen strikeouts?”

Interestingly, the story twisted and was expanded over the years, as folklore tends to do. When speaking later in life, Eisenstat was fond of pointing out while Feller was striking out 18, it should be remembered that he (Eisenstat) had a no-hitter into the eighth inning. The trivia was repeated in several obituaries upon Eisenstat’s death in 2003. Alas, it’s too good to be true. Cleveland singled in the first and fourth innings, along with the two hits in the ninth.

Eisenstat completed 1938 with a career-high nine wins as Detroit rounded out the first division, going 84-70, 16 games behind the Yankees. Greenberg finished third in the American League MVP voting.

Eisenstat started the third game of the 1939 season for Detroit, again matched up with Feller who settled for 10 strikeouts and a 5-1 Cleveland victory. Eisenstat didn’t start again until June, giving up 14 runs in eight relief appearances in between. In his final appearance for the Tigers, starting the back end of a doubleheader on June 10, Eisenstat’s teammates gave him all the runs he needed to secure his final victory for Detroit, a 17-5 laugher over the Senators. Greenberg homered again in support of his friend.

Four days later, Eisenstat was traded to Cleveland along with cash for six-time All-Star outfielder Earl Averill. Then 37 and at the tail end of a Hall of Fame career, Averill was cleared out to make room for younger players in Cleveland’s outfield following years of contract squabbles with Vice-President Cy Slapnicka. With the Indians, Eisenstat continued to work as a swingman in manager Oscar Vitt’s bullpen.

Eisenstat made a strong first impression in Cleveland, pitching two perfect innings with three strikeouts on back-to-back days after his acquisition. He picked up a victory in his third appearance and earned his first start on July 5. Eisenstat lost despite giving up only two runs to Chicago. He then pitched a complete game victory on three days’ rest in his next outing, allowing one run to St. Louis. His only career shutout came on August 25, at Cleveland’s League Park against the Philadelphia Athletics, in which he scattered six hits. Eisenstat never started more than three consecutive appearances for Vitt, but he pitched effectively: 6-7 with a 3.30 ERA in 26 games (11 starts) after posting a 6.98 ERA with Detroit. Cleveland finished in third place with an 87-67 record.

Eisenstat settled primarily into relief work with Cleveland over the final three years of his career. A leg injury in late May 1940 caused him to miss six weeks. He returned with a start in Washington on July 16 that lasted just two innings.20 Over the next two months, he made 14 relief appearances, pitching to a 1.95 ERA in 32 1/3 innings over that span while Cleveland battled Detroit and New York for the pennant.

The summer of 1940 brought the infamous “Crybaby Indians” – a player-led rebellion against Vitt that garnered national attention as Cleveland players pushed back against their manager, whom they described as demeaning and cruel. Eisenstat was not directly part of the revolt, however, as the flare-up was at its hottest in mid-June when he was sidelined by his leg injury. He would later express his opinion on the matter.

Vitt gave Eisenstat another starting opportunity in the heat of the pennant race. A six-game losing streak in early September had erased Cleveland’s 3½ game lead, but an Indians’ victory on September 8 kept them tied for first with Detroit. On September 9, Eisenstat got the start against the White Sox – a win would have put Cleveland alone in first place with the Tigers idle. Eisenstat pitched well enough to win, yielding only two runs in eight innings, but the Indians managed only one run on four hits, and Eisenstat took a hard luck 2-1 loss. He lost his next start, 3-2, despite another eight solid innings, but Vitt seemingly closed the book on him. Cleveland lost the pennant by one game to the Tigers, and Eisenstat appeared in only one of the Indians’ last 12 contests. Unsurprisingly, Vitt was not asked to return as manager in 1941.

In January, the New York Daily News ran a long quote from Eisenstat addressing the Vitt controversy that was reprinted in the Cleveland Plain Dealer. Never a star player, it was likely the longest quote attributed to Eisenstat during his playing career:

The Indians did what any self-respecting men would do, explained Eisenstat. “The press was on Vitt’s side all along. I don’t blame ‘em. Ossie always was good copy for them, clowning and gagging and making sensational statements. He argued with the umpires only on Sundays, and you know what that means – he was arguing for the grandstand’s benefit, not his players’. But Vitt was not a good ballplayers’ manager. He’d never take the rap for himself, much less for one of his players. He’d ride his own players so cruelly when they went badly, you’d think he was managing the opposing club… All right, you’ll say we should have faced him man to man in the clubhouse with our complaint. We did! Rather, we tried. He would just laugh us down, and not listen. A ball player – no, any human being, can stand just so much ridicule… Another thing I want to get off my chest: Don’t let anyone think for a moment the Indians were dogging it the last month of the season. We were tearing our innards apart to win in the stretch, but we just couldn’t buy a base hit or a long fly when we got runners in scoring position.”21

Eisenstat pitched entirely out of the bullpen for new Cleveland manager Roger Peckinpaugh in 1941, going 1-1 with a 4.24 ERA and an uncharacteristically high 16 walks in 34 innings.

Peckinpaugh was replaced in 1942 by the Indians’ all-star shortstop, Lou Boudreau, who took the reins as a 24-year-old player/manager. Eisenstat bounced back with a 2-1 record and a 2.45 ERA in 29 games over 47 2/3 innings. He regained his excellent control, walking only six batters.22

Eisenstat made only one start in 1942, in a May 16 doubleheader against Washington.23 He was knocked out in the third inning, charged with four runs allowed, and suffered the final loss of his career.

Over his final 24 appearances, Eisenstat pitched 39 innings with a 2-0 record and 1.62 ERA. If the 26-year-old had more innings in his left arm, it would never be known. The war in Europe was raging and Eisenstat retired from baseball to join the effort.

His career record with Brooklyn, Detroit and Cleveland was 25-27 with a 3.84 ERA over 165 appearances (33 starts). His 11 complete games included one shutout. In 478 2/3 innings, he walked only 114 batters, a rate of 2.1 per nine frames.

Eisenstat spent the winter of 1942 in Cleveland training with the Weatherhead Company, an automobile manufacturer making aviation equipment for the war effort.24 He was called to report to the Army in June 1943 for the remainder of the war.25 He did his basic training at Mitchel Field on Long Island, New York, and was “assigned as a technical inspector for vehicles pertaining to airplanes.” He was eventually promoted to corporal.26

After the war ended in 1945, Eisenstat returned to Cleveland. “It was the last place I was before the service, and I sort of liked it for raising a family.”27 He ran a dry-cleaning business in East Cleveland in the 1940s and later opened the GAE Hardware Store at the Van Aken Shopping Center. He sold the business in the 1960s and worked for Curtis Industries as a sales manager and vice president until retirement.

Eisenstat was inducted into the Michigan Jewish Sports Hall of Fame in 1993, joining Greenberg, a 1985 inductee. Regarding antisemitism during his career, Eisenstat once said “In the minor leagues there was more antisemitism than the big leagues. I never used it as an excuse. A lot of people who were not successful used it as an excuse, (saying), ‘I didn’t get the job because I was Jewish.’”28

Eisenstat died on March 21, 2003, survived by Evelyn (Rosenberg), his wife of 64 years, their daughter Linda, and four grandchildren. He is buried at the Mount Olive Cemetery in Solon, Ohio.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Malcolm Allen and Rick Zucker and fact-checked by Tim Herlich.

The author would like to thank Ann Sindelar of the Western Reserve Historical Society for her time and Heber MacWilliams for his genealogical assistance.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted www.ancestry.com, www.baseball-reference.com, www.retrosheet.org, www.newspapers.com, and sabr.org/bioproject.

Notes

1 Russell Schneider, Tribe Memories: The First Century (Moonlight Publishing, 2000), 40.

2 Baseball-Almanac.com and the Jewish Baseball Museum.com list roughly 25 Jewish players who took the field in the decade prior to the U.S. entry into World War II. See https://www.baseball-almanac.com/legendary/Jewish_baseball_players.shtml and https://jewishbaseballmuseum.com/the-roster/.

3 Barney Kremenko, “Baltimore’s Titlists Face Picked Team,” Brooklyn Times Union, June 20, 1934: 3A.

4 Bernard I. Kremenko, “Scholastic Mirror,” Brooklyn Times Union, April 20, 1932: 3A.

5 Bernard I. Kremenko, “Scholastic Mirror,” Brooklyn Times Union, June 6, 1932: 2A.

6 Harold F. Parrott, “Madison Nine Beaten By Textile, 2-1, for City P.S.A.L Title,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 19 1932: C3.

7 Joseph J. Gorevin, “Madison Has Three on Eagle’s All-B’klyn 1932 Scholastic Nine,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 26, 1932: C5.

8 “Eisenstat Hurls Perfect Game as Madison Scores,” Brooklyn Times Union, May 30, 1933: 9.

9 Bernard I. Kremenko, “Times Union’s Brooklyn All P.S.A.L. Nines Listed,” Brooklyn Times Union, June 25, 1933: 2A.

10 Barney Kremenko, “Experienced Players Dominate Brooklyn’s Baseball All-Scholastic,” Brooklyn Times Union, June 14, 1934: 3A.

11 Si Burick, “Si-ings,” Dayton Daily News, August 14, 1934: 8.

12 Bill McCullough, “Stengel Will Drop at Least a Half-Dozen,” Brooklyn Times Union, August 13, 1934: 1A.

13 “Eisenstat Blanks Detroit for Five Frames; Dodgers Take Him,” Dayton Herald, March 25, 1935: 15.

14 Bob Husted, “The Referee,” Dayton Herald, September 12, 1935: 18.

15 Bill McCullough, “Several Dodgers Plan Early Spring Training Licks,” Brooklyn Times Union, February 15, 1936: 1A.

16 Frey made a league-leading 62 errors in 1936 playing shortstop and second base.

17 Bill McCullough, “Eisenstat Confident He’ll Stay in Majors Next Year,” Brooklyn Times Union, November 10, 1936: 5A.

18 “Eisenstat Hurt Badly in Drill,” Detroit Free Press, May 25, 1938: 17.

19 Ira Berkow, Hank Greenberg: The Story of My Life (New York: Random House, 1989), 119.

20 “Smith to Oppose Ken Chase Today,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, July 14, 1940: 1-C.

21 Gordon Cobbledick, “Plain Dealing,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, January 7, 1941: 17; Hy Turkin, “Fungoes,” Daily News (New York), January 5, 1941: 80.

22 Both baseball-reference.com and retrosheet.org have a discrepancy on Eisenstat’s 1942 earned run totals. Both sites list his season total as 13 earned runs allowed but the game logs individually add up to 14. If he had allowed 14 earned runs, his 1942 ERA is 2.64 and his career ERA is 3.85. The author has reached out to both sites with the discrepancy for further research. For more information, see https://www.retrosheet.org/DiscrepanciesWithOfficialData.pdf.

23 Eisenstat made more starts, appeared in more games, and won more games against the Washington Senators than any other opponent in his career. He made seven of his 33 career starts against Washington, finishing with a 7-4 record and 3.31 ERA in 108 2/3 innings.

24 “Ballplayers are Working in Plants,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, October 25, 1942: 4-C.

25 “Eisenstat Gets Call to Report for Induction,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, May 8, 1943: 16.

26 “In the Service,” The Sporting News, January 13, 1944: 11.

27 Margi Herwald, “Boys of Summer Look Back,” Cleveland Jewish News, July 6, 2001.

28 Herwald.

Full Name

Harry Eisenstat

Born

October 10, 1915 at Brooklyn, NY (USA)

Died

March 21, 2003 at Beachwood, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.