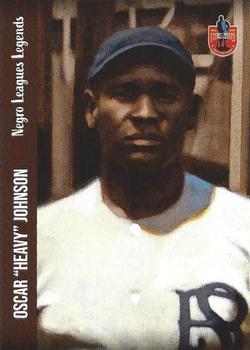

Heavy Johnson

Oscar “Heavy” Johnson was briefly one of the premier power hitters of the Negro Leagues. After spending nearly eight prime seasons playing for the U.S. Army’s 25th Infantry Wreckers (where he was the batterymate of Hall of Famer Wilber “Bullet” Rogan), Johnson joined the Kansas City Monarchs in 1922 and immediately won back-to-back Negro National League (NNL) batting titles and the 1923 Triple Crown.

Oscar “Heavy” Johnson was briefly one of the premier power hitters of the Negro Leagues. After spending nearly eight prime seasons playing for the U.S. Army’s 25th Infantry Wreckers (where he was the batterymate of Hall of Famer Wilber “Bullet” Rogan), Johnson joined the Kansas City Monarchs in 1922 and immediately won back-to-back Negro National League (NNL) batting titles and the 1923 Triple Crown.

Johnson is not a member of the National Baseball Hall of Fame—nor has he ever gotten particularly close. Despite that, there are very few players in history who can approach his offensive dominance. Among players with 1,000 or more major-league plate appearances, Johnson’s .370 batting average ranks second all time, just four points behind Josh Gibson (and four points ahead of AL/NL leader Ty Cobb). As early as October 1922, phrases like “Johnson is Babe Ruth,”1 “ Babe Ruth’ has nothing on ‘Heavy’,”2 “the Black Babe Ruth,”3 and “the Babe Ruth of the colored league”4 began appearing in papers to describe his hitting prowess.

Oscar Johnson was born April 20, 1895, in Atchison, Kansas. Also the birthplace of aviatrix Amelia Earhart, Atchison is about 50 miles northwest of Kansas City, Missouri and sits along the Missouri River. Johnson’s father (Frank, born October 1848) and mother (Harriet, born February 1857) were both born in Lebanon, Virginia, “almost certainly” as slaves.5 Frank, a laborer in a brick yard, and Harriet were married in 1872. They would have 11 children, with nine still living when the 1900 Census was taken. Oscar was the youngest of the nine. Not much else is known about his youth beyond the fact that he received a sixth-grade education.6

On December 10, 1913, Johnson (by then living in Youngstown, Ohio) enlisted in the Army at Columbus Barracks in Ohio. He listed 1892 as his birth year, adding three years to his actual age (21 instead of 18).7 He would use the 1892 birth date for the rest of his life.8

Johnson was assigned to Company K in the 25th Infantry Regiment, one of four all-Black US Army units formed in 1866 and collectively known as the “Buffalo Soldiers.” The 25th Infantry’s baseball team was established in 1893 by Colonel Andrew S. Burt.9 On January 15, 1913, the 25th Infantry arrived at Schofield Barracks on the Hawaiian island of Oahu. It was here that the regiment baseball team became known as the “Wreckers”—one of the top professional teams in the country. In this era before the founding of the NNL, playing baseball for Uncle Sam was among the steadiest paychecks a Black ballplayer could find.

In Hawaii, the Wreckers were part of an incredible melting pot of baseball talent. They played against other Army teams, civilian clubs (that were mostly organized by ethnicity), traveling All-Star squads made of major- and upper minor-league players, teams from the Pacific Coast League or universities, and anyone else who wanted to test their skill against the Wrecking Crew.

A “Johnson” appeared for the Wreckers in a contest against the 2nd Infantry on May 14, 1914, batting eighth and playing right field.10 He made at least six more appearances in 1914. The evidence is inconclusive, but this could be Oscar Johnson. Additionally, there is another “Johnson” who appeared in at least two games in the winter of 1913-14, but it is less likely (though not impossible) that this is Oscar.

In 1915 Johnson was definitely a full-time member of the team. The 25th Infantry team was in first place with an 8-1 record when the Schofield Barracks League finished play on September 22. That day, in a 7-3 win against the 1st Infantry in front of 8,000 fans, Johnson hit his first homer as a Wrecker. The Honolulu Advertiser wrote, “When Mr. Johnson connected, the ball went sailing to the score board. The score board is 475 feet from home plate. When [center fielder] Wheeler reached the ball, Johnson was drinking a pop on the bench.”11 In 34 box scores found for the 1915 Wreckers against all competition, Johnson batted .333 and slugged .552 in 24 appearances.12

The 25th Infantry opened 1916 with two games against the traveling Olympic Club of San Francisco. These games were the first that Walter “Dobie” Moore would play with the Wreckers. The Olympics’ arrival was highly publicized, but the last game of their tour was spoiled by a Johnson walk-off home run.13 In June, the Wreckers finished atop the Oahu Senior League with an 8-1 record. The Honolulu Star-Bulletin named Johnson to their All-Star team, along with teammates Rogan, Allie Crafton, Lemuel Hawkins, and Clyde Aulston.14

On August 27, Rogan (as pitcher) and Johnson (who had transitioned from the outfield to become the team’s primary catcher) combined for a dominant 10-0 win against the Cruiser St. Louis team. Rogan allowed just a lone single while striking out 20 and hitting a home run. Johnson clubbed two home runs, a triple, and a single. Of the 27 outs recorded by the Wreckers, Johnson had 21 putouts and four assists as he caught three soldiers stealing. He would have caught a fourth if his shortstop hadn’t dropped the throw.15

The 1916 Post League season stretched into January 1917 as the 25th Infantry (who finished 9-2) played a best-of-three series against the 32nd Infantry for the championship. The 25th won the opener, 14-1. Johnson and Rogan each collected three hits.16 A week later, the 25th earned the title with a 2-0 victory.17 In 39 box scores that have been located from the Wreckers’ 1916 campaign, Johnson hit .318 with a .563 slugging percentage in 38 games. In addition to five home runs, he legged out 10 triples and stole 15 bases. Rogan batted .312 while the rest of the team combined to hit .229.18

In 1917, Rogan went on furlough for three months. That didn’t stop the Wreckers from going 8-0 in the Oahu Service League. With Rogan back in action in September, Johnson hit for the cycle in a 16-2 win against a combined 1st and 32nd Infantry team. He had five hits in all, collecting two singles.19 He played in 31 of the Wreckers’ 33 games for which box scores have been found in 1917 and batted .379 with six homers and a .661 slugging percentage.20

During that season, Johnson’s nickname “Heavy” began to appear in the papers.21 In addition to his offensive prowess, he stood 5-foot-7 and weighed 200 pounds (though some sources list him as tall as 6-feet and 250).22 His “neck bulged and his chest was massive” while “his biceps matched most men’s thighs.”23 Johnson threw right-handed but there is no conclusive evidence that he batted either left- or right-handed.

The Wreckers steamrolled the rest of the Oahu-Service League in 1918, going 8-0 in the First Series, scoring 54 runs and allowing just 10. On May 26, Johnson caught Rogan’s no-hitter against Waikiki, tagging out a runner in the first inning who tried to steal home.24 Two weeks later, he caught a Rogan one-hitter and hit for the cycle again (with an additional single for another five-hit game).25

The Honolulu Star-Bulletin named Johnson the catcher on their All-Star team for the circuit.26 The Second Series began in late July. However, the Wreckers soon learned that they would be relocating to Arizona. Their final game in Hawaii was played on August 11. Johnson went 2-for-4 with a double in a 4-0 win against the Marines.27 In 12 available box scores from the 1918 season, Johnson hit .444 and slugged .711.28

Coverage of the Wreckers in Hawaii was extensive and descriptive. They were beloved by the locals and known across the country. The Spalding Company even approached them about sponsoring a West Coast tour, but it never came to fruition because of the team’s military obligations.29 Overall, between 1914 and 1918, Johnson batted .346 in Hawaii over his 111 appearances for which box scores have been located. In 422 at-bats, he also clubbed 18 doubles, 22 triples, and 14 homers for a .592 slugging percentage, with 101 runs scored, and 30 stolen bases. Only Rogan (.338 average, .624 slugging, 22 homers, 39 steals) could boast similar numbers among his teammates. Only Rogan (.338 average, .634 slugging, 22 homers, 38 steals) could boast similar numbers among his teammates.30

While the 25th Infantry was making its way to the mainland from Hawaii, the Battle of Ambos Nogales broke out on the United States–Mexico border on August 27. Four Americans and about 129 Mexicans were killed with approximately 330 wounded. As a result of the conflict, a two-mile barbed wire fence was installed to separate Nogales, Arizona and Nogales, Mexico. This was the first permanent border barrier constructed between the two countries.31

The 25th Infantry began arriving on August 30 and were assigned to guard the new border wall.32 “After that, not much baseball was played,” Wreckers teammate William “Big C” Johnson told author Phil S. Dixon.33 Once World War I ended in November, there would be more time for baseball.34

Oscar Johnson was honorably discharged from the Army in March 1919, but he soon re-enlisted (perhaps immediately).35 The Arizona District League commenced on June 14 with a 21-2 win over the 1st Cavalry.36 That summer, Johnson, Rogan, Moore, and pitcher George Jasper also played for the integrated Nogales Nationals.37

Pittsburgh Pirates outfielder Casey Stengel brought an all-star team of major- and high minor-league players to Nogales in November 1919. Stengel’s team arrived with an undefeated record, including a pair of victories over the Chicago American Giants, who would finish atop the Negro National League the following season.38 Though there are no known box scores for the Wreckers 1919 season, they were 22-2 leading up to a three-game series against Stengel’s squad.39 Johnson had definitely re-enlisted by this time and was available. However, the 25th Infantry would be without Rogan and other prominent players like Crafton, Hawkins, Fred Goliah, and Saki Smith.40

Despite the key absences, the Wreckers won the first game, 5–4. After Stengel’s team scored all of its runs in the first inning against Jasper, the 25th’s comeback was highlighted by a Moore home run. Pitchers named “Johnson” started the second and third games for the Wreckers, though it’s not clear whether it was Oscar or William Johnson. (By January 1920, “Big C” was no longer living in Nogales according to the census, but he may still have been with the Wreckers in November 1919.) Either way, the hurler was inexperienced—and it showed. Game Two was a slugfest with Stengel’s All Stars winning, 14-11.41

In Game Three, the Wreckers fell behind by six runs in the second inning. Jasper relieved Johnson (who moved to catcher) and shut Stengel’s side down the rest of the way while the 25th completed the 8-6 comeback win.42

Immediately after the third contest, two more games were added to the series. They received much less coverage. Game Four was won by the Wreckers, 8-6. The fifth and final game was a blowout with Stengel’s team winning, 19-3. One can only wonder which 25th Infantry pitchers were available for that game given the workloads of Johnson and Jasper throughout the series.43

In June 1920, the 25th Infantry were among more than 400 soldiers in St. Louis for the Olympic trials ahead of the 7th Olympic Games in Antwerp, Belgium.44 Although Rogan, Moore, and many of the Wreckers’ stars had already moved on, there was clearly immediate interest in some players from the 25th upon their arrival. On June 24, Johnson appeared in a game for the NNL’s St. Louis Giants against the Cuban Stars, coming off the bench to catch and collecting his first major-league hit (a single).45 When the 25th Infantry played those same Giants on June 28, Johnson was in the lineup for the Wreckers. The soldiers prevailed, 4-1.46

A few days later, the Chicago Defender reported that the Giants had signed Johnson, Mose Herring, and an infielder named Stewart (first name unknown) from the 25th Infantry. Johnson was described as “a catcher who is said to be the peer of them all.”47

On July 4 and 5, Johnson made two starts for the Giants, the first a 4-2 loss to the Kansas City Monarchs. The Monarchs lineup featured former Wreckers Moore and Rogan batting fourth and fifth. The next day, Johnson started behind the plate in St. Louis’s 10-6 win over the Cuban Stars. He had two hits—one a bases-loaded triple in the seventh inning.48 That would be Johnson’s last appearance for the Giants, however, as he “was kept out of the game after Monday by the Army authorities.” Herring and Stewart were allowed to stay with St. Louis.49 The Army didn’t seem to be in a rush to let its biggest diamond asset leave before they had to. Unfortunately, 25th Infantry results and box scores are very hard to come by for the rest of 1920 and 1921.

While Johnson was a great ballplayer for Uncle Sam, he did not have a great reputation as a soldier. Johnson “was the regiment misfit,” wrote William McNeil. He added that Johnson “was in the guardhouse as often as he was out of it. If an important baseball game happened to coincide with his sentence, however, the colonel would order Johnson’s release and, if Johnson played well in the game, the colonel would let him stay out of the guardhouse—until his next offense.”50

By May 1922, Johnson was finally honorably discharged. He joined many of his former Wreckers teammates (Rogan, Moore, Hawkins, Branch Russell, and William Linder) on the Kansas City Monarchs. On May 20, he made his first appearance, going 0-for-1 in a win against the St. Louis Stars. Against the same club the next day, he started and went 2-for-4 with a double. Johnson’s first Monarchs’ homer also came against the Stars, on June 2.51

By May 1922, Johnson was finally honorably discharged. He joined many of his former Wreckers teammates (Rogan, Moore, Hawkins, Branch Russell, and William Linder) on the Kansas City Monarchs. On May 20, he made his first appearance, going 0-for-1 in a win against the St. Louis Stars. Against the same club the next day, he started and went 2-for-4 with a double. Johnson’s first Monarchs’ homer also came against the Stars, on June 2.51

Johnson’s debut campaign for the Monarchs was magnificent. He finished with a .406 batting average and .715 slugging percentage in 68 games (including league and interleague contests, and games against major Blackball teams). He clubbed 19 doubles, 11 triples, and 11 homers while stealing nine bases.52

In 1922-23, Johnson played in the integrated California Winter League with the Los Angeles White Sox. His teammates included many Monarchs and Wreckers (Hawkins, José Méndez, Rube Curry, Bob Fagan, Pinky Ward, and George Carr) as well as Biz Mackey.53 Los Angeles won the championship and Johnson led the league in batting at .340 (16-for-47, just .0004 ahead of Mackey).54

The Monarchs opened the 1923 season at home against the Chicago American Giants on April 28. Johnson went 0-for-3 but, the next day, he had his first of many big performances that season. He went 4-for-5 with a home run, triple, and pair of doubles against Chicago, driving in five runs and scoring three. He hit .425 in May, highlighted by a 3-for-3 game on May 21 with a pair of home runs, a triple, and six runs batted in. By the end of the month, he had already hit nine home runs in just 25 games—seven in an eight-game span (all on the road).55

On June 4 against Milwaukee, Johnson had the first three-homer game in Monarchs history.56 He went 4-for-5 and drove in five that day. On July 1, he had another four-hit explosion, driving in six against Toledo.57 As part of a three-hit, five-RBI day on July 31, Johnson hit the first home run at Kansas City’s new Muehlebach Field (a stadium the Monarchs would share with the Kansas City Blues of the American Association before it became the home of the Kansas City Athletics in 1955).58

On August 1, Johnson married 23-year-old Juanita Powell of Kansas City. Unfortunately, nothing else is known about Juanita and their relationship beyond the fact that the marriage apparently didn’t last though the end of Johnson’s playing career.59

Johnson’s incredible 1923 campaign resulted in another .400 season and the NNL Triple Crown. His .406/.471/.722 slash line over 98 games included the league’s top slugging percentage, and he also paced the circuit in OPS (1.193), homers (20), RBIs (120), doubles (32), and runs scored (91).60

After the season, Johnson played his second and final season of winter ball. He joined the Santa Clara Leopardos, considered not only the best Cuban League team ever, but simply one of the best baseball squads, period. The roster boasted future Hall of Famers Oscar Charleston and Méndez, plus strong candidates like Johnson, Moore, Alejandro Oms, and Oliver Marcell. The depth of talent also featured Frank Duncan, Frank Warfield, Bill Holland, Dave Brown, Eustaquio Pedroso, and Curry. The Leopardos went 36-11-1 and won the league title comfortably by 11½ games. In 15 appearances, Johnson hit .370 and slugged .556 before he left the team early to return to the United States for an unknown reason.

The 1924 campaign was Johnson’s final season with the Monarchs. While he didn’t repeat his 1923 totals, he still batted .366 with five home runs and 55 RBIs, finishing third in the NNL in average and hits, and fourth in total bases. Including non-league competition, some sources report that Johnson hit more than 60 homers that year.61

After winning their third consecutive NNL title, Johnson and the Monarchs played in the very first Colored World Series against Hilldale of the Eastern Colored League (ECL). Johnson hit .296 in the series and slugged .407—modest totals for him, but well above the team figures of .228 and .295, respectively. Ahead of the pivotal Game Eight, the series was tied at three games apiece (one tie) with five wins needed to clinch the championship.

Johnson doubled, but he uncharacteristically dominated the game with his defense. In the fifth inning with the game scoreless, he robbed George Johnson of a triple. In the eighth with Hilldale up 2–0, he made a “shoestring catch” to rob Judy Johnson of a hit. Oscar Johnson kept the Monarchs’ deficit to just two by throwing out Carr at the plate on an Otto Briggs hit in the top of the ninth. In the bottom of the inning, he contributed to the game-winning rally by getting hit in the buttocks to load the bases with two outs ahead of Duncan’s decisive two-run single.62

Hilldale won the ninth game, forcing a winner-take-all Game 10. With Méndez starting against Script Lee, the game was scoreless through seven. In the bottom of the eighth, Johnson doubled home Moore for what proved to be the series-winning run. Kansas City tacked on four more to put the game out of reach, with Johnson scoring on Newt Allen’s single.

In March 1925, Johnson was traded to the Baltimore Black Sox of the ECL for Wade Johnston.63 Batting behind Jud Wilson and John Beckwith,64 Johnson hit .327 and slugged .538. Midway through 1926, Beckwith joined the Harrisburg Giants. After hitting .350, Johnson joined him that offseason. In Harrisburg, Johnson was part of one of the greatest outfields of all time with Fats Jenkins in left, Charleston in center, and Johnson in right (with Rap Dixon also playing when he wasn’t touring the Far East). In 1927, Johnson slashed .379/.461/.568 in 58 games to rank third in the ECL in batting, on-base percentage, and slugging.

Johnson returned to the NNL in 1928 with the Cleveland Tigers. Despite hitting .387 and slugging .547 in 20 games, Johnson was released along with several other players, general manager S.M. Terrell, and manager Duncan when owner M.C. Barkin cleaned house.65 Barkin complained that “several of the players were not keeping in condition and that the manager had no control over the players.”66 Johnson joined the NNL’s Memphis Red Sox for the remainder of the season and hit .331 in 49 games.

Outside of five appearances for Memphis spread out over a two-month span in 1930, it is not known what Johnson did over the next two years. He started 1931 with the independent Dayton Marcos but left the club to join the Louisville White Sox of the NNL in June. Johnson went 6-for-21 with a homer for Louisville before returning to Dayton.67

Johnson joined the Newark Browns of the upstart East-West League in 1932, once again recruited by manager Beckwith. Before the East-West League season even started, though, many players had jumped to other teams.68 Newark’s club lasted just four games before folding, losing them all. Johnson saw action in two of them, going 0-for-3. The Negro Leagues continued to suffer through the Depression and the East-West League folded before the end of 1932. By the time the second Negro National League commenced in 1933, Johnson’s major-league career was over.

Across all or parts of 11 seasons in major Negro Leagues, Johnson hit .370 with a .428 on-base percentage and .592 slugging percentage. Per 162 games, he averaged 109 runs, 215 hits, 39 doubles, 17 triples, 19 home runs, 141 runs batted in, 16 stolen bases, and six wins above replacement.69 Though he never played at the top level again, Johnson reportedly played for the independent Detroit Cubs in 1935 at age 40.70

On October 17, 1936, Johnson married Cora Mason in Wayne, Indiana. This marriage lasted at least through 1952 and likely until his death. Piecing together what Johnson did after his playing career is difficult, but public records provide some clues. In 1940, he was living in Dayton, Ohio and working as a laborer.71 Two years later in the same state, he was employed by the Chester Garage Company.72 Johnson and his wife lived in Cleveland as of 1950, with Cora’s daughter Louise and Louise’s family. Johnson was a flour blender for a baking company.73

Oscar Johnson died on October 9, 1960, in Cleveland, Ohio. There is no obituary. There is no gravesite. All we know is that a tremendous baseball player quietly passed.

In 2006 Johnson was one of 94 preliminary candidates for the National Baseball Hall of Fame via the Committee on African-American Baseball, but he did not make the final ballot. If his perceived lack of longevity was the sticking point, it’s worth noting that his former Wreckers and Monarchs teammate Moore received further consideration despite playing only six seasons in major Negro Leagues. When Johnson spent eight years in the Army, he did so, in part, because it was one of the few reliable options where a Black ballplayer could earn a steady paycheck while the American and National Leagues remained segregated. Although the competition he faced there varied greatly, Johnson’s statistics kept pace with Hall of Famer Rogan’s (and both were far above everyone else).

Johnson, who began his career as a catcher before shifting to the outfield, was also burdened by his reputation as an “unpolished fielder.”74 Modern metrics like Total Zone Rating agree that he was a below-average fielder, costing his team about seven runs per 162 games. But that pales in comparison to the 59 he added with his bat in the same span.75

Johnson might compare well with modern players like Manny Ramírez or Gary Sheffield—enormous bats who were among the worst defenders in history by advanced metrics. But he may have been closer to Harry Heilmann, a peer of Johnson’s (1914-32) who similarly dominated at the plate but was not as big a defensive liability.

In 2012, Johnson was inducted into the Kansas Baseball Hall of Fame along with 13 other Negro Leaguers.76 In 2021, a mural created in Atchison by artist Vaughn Schultz was painted that depicted Johnson in mid-swing.77

Thanks to the tireless work of researchers Gary Ashwill, Scott Simkus, Mike Lynch, Kevin Johnson, and Larry Lester of the Seamheads Negro Leagues Database, the statistics of Johnson and several thousand Negro League players are presented as major-league statistics on Baseball Reference. Because of that, we can apply tools such as Bill James’ similarity scores and Black Ink scores (a measurement of “how often a player led the league in a variety of ‘important’ stats”) to Negro League players. By these measures, Johnson’s most similar player is Hall of Famer Willard Brown and his Black Ink score is 31. The average Hall of Famer has a score of 27 (and Johnson’s score does not include his prime years in the Army).78

Yet, when more Negro Leaguers were considered for Hall of Fame induction in 2022, Johnson was not included on the Early Baseball Era Committee’s ballot. Oscar Johnson seemed to fade from memory as quickly as he burst on the Negro Leagues scene. Modern researchers have rebuilt his playing record from the box score up and contemporary analysis suggests he may be one of the greatest overlooked legends in Negro Leagues history.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Malcolm Allen and Rory Costello and fact-checked by Ray Danner.

Sources

In addition to sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted www.baseball-reference.com and game logs provided by Kevin Johnson of the Seamheads Negro Leagues Database.

Notes

1 “Famous Colored Ball Club to Tour State with Bears,” Black Dispatch (Oklahoma City, Oklahoma), October 5, 1922.

2 “Sporting News,” Buffalo (New York) American, October 26, 1922.

3 “Champion Monarchs Play at Rick Monday,” Birmingham (Alabama) News, September 16, 1923.

4 “Trident-Monarch Game a Thriller,” Morning Chronicle, August 19, 1923.

5 Gary Ashwill, “He Ain’t Heavy, He’s My Brother,” Agate Type, https://agatetype.typepad.com/agate_type/2007/09/he-aint-heavy-h.html, accessed July 21, 2022.

6 1940 United States Federal Census. Ancestry, https://www.ancestry.com/sharing/29955112?h=478d39.

7 Gary Ashwill, “Will the Real Oscar Johnson Please Stand Up?” Agate Type, https://agatetype.typepad.com/agate_type/2007/09/will-the-real-o.html, accessed July 21, 2022.

8 Ashwill, “He Ain’t Heavy, He’s My Brother”

9 Jerry Malloy, “The 25th Infantry Regiment Takes the Field,” The National Pastime, Vol. 15 (1995), accessed July 21, 2022.

10 “Saunder’s Outfit Star at Batting,” Honolulu Advertiser, May 16, 1914.

11 “Post Championship is Won by Twenty-Fifth,” Honolulu Advertiser, September 23, 1915.

12 Darowski, “25th Infantry Wreckers.”

13 “Burke’s Men Meet Defeat in Great Contest with Twenty-Fifth Infantry Diamond Stars,” Honolulu Advertiser, February 27, 1916.

14 “Schofield Has Say on Leading Diamond Stars,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, August 12, 1916.

15 “Navy Drops One to Sluggers of 25th Infantry,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, August 29, 1916.

16 “Wreckers Start Champ Series at Schofield, Beating 32nd 14 to 1,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, January 22, 1917.

17 “Wreckers Win Big Post League Pennant at Schofield Barracks,” Honolulu Advertiser, January 29, 1917.

18 Darowski, “25th Infantry Wreckers.”

19 “Great Slaughter at Moiliili Park,” Honolulu Advertiser, September 10, 1917.

20 Darowski, “25th Infantry Wreckers.”

21 “‘Heavy’ Johnson Breaks Up Game with Chinese on Sunday,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, July 23, 1917.

22 James A. Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues, (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 1994), 440.

23 Phil S. Dixon, Wilber “Bullet” Rogan and the Kansas City Monarchs, (Jefferson: McFarland & Company, 2010), 51.

24 “Rogan Pitches No-hit Game,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, May 27, 1918.

25 “Coast Defense Fails to Swat Pitcher Rogan,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, June 10, 1918.

26 “All-Star Squad of Oahu-Service League Selected,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, July 5, 1918.

27 “Wreckers Farewell with Hard-Earned Victory Over Pearl Harbor Marines,” Honolulu Advertiser, August 12, 1918.

28 Darowski, “25th Infantry Wreckers.”

29 William F. McNeil, Black Baseball Out of Season, (Jefferson: McFarland & Company, 2015), 57.

30 Darowski, “25th Infantry Wreckers.”

31 Carlos Francisco Parra, “Battle of Ambos Nogales signaled birth of border fence,” Nogales International, accessed July 21, 2022.

32 McNeil, Black Baseball Out of Season, 60.

33 Dixon, Wilber “Bullet” Rogan and the Kansas City Monarchs, 28.

34 McNeil, Black Baseball Out of Season, 61.

35 Ashwill, “Will the Real Oscar Johnson Please Stand Up?”

36 “Initial Game in Series of the Military District League,” Daily Morning Oasis (Nogales, Arizona), June 15, 1919.

37 Bill Staples Jr., “The Making of a Monarch: Dobie Moore, Casey Stengel, and the Lost Box Scores of 1919,” International Pastime, http://billstaples.blogspot.com/2019/12/the-making-of-monarch-dobie-moore-casey.html, accessed July 21, 2022.

38 Staples Jr., “The Making of a Monarch: Dobie Moore, Casey Stengel, and the Lost Box Scores of 1919.”

39 “Stengel to Play Camp Little Teams November 3, 4, 5,” Tucson Citizen, November 2, 1919.

40 “Nogales Doughboys Will Play Three Games with Casey Stengel’s Stars,” Arizona Daily Star, October 31, 1919.

41 Staples Jr., “The Making of a Monarch: Dobie Moore, Casey Stengel, and the Lost Box Scores of 1919.”

42 Staples Jr., “The Making of a Monarch: Dobie Moore, Casey Stengel, and the Lost Box Scores of 1919.”

43 Staples Jr., “The Making of a Monarch: Dobie Moore, Casey Stengel, and the Lost Box Scores of 1919.”

44 “400 Soldiers to Try out for Olympic Team,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, June 30, 1920.

45 Heavy Johnson Game Logs provided by the Seamheads Negro League Database, July 24, 2022.

46 “Infantry Team Beats St. Louis Giants, 4-1,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, June 29, 1920.

47 Gary Ashwill, “From the Wreckers to the St. Louis Giants,” Agate Type, https://agatetype.typepad.com/agate_type/2006/11/from_the_wrecke.html, accessed July 21, 2022.

48 “Giants Gain Victory Over Cuban Stars, 10-6,” St. Louis Globe Democrat, July 6, 1920.

49 Dr. Layton Revel and Luis Munoz, “Forgotten Heroes: Oscar “Heavy” Johnson,” http://www.cnlbr.org/Portals/0/Hero/Oscar-Heavy-Johnson.pdf, accessed July 21, 2022.

50 McNeil, Black Baseball Out of Season, 61.

51 Heavy Johnson Game Logs provided by the Seamheads Negro League Database, July 24, 2022.

52 Baseball-Reference.com, accessed August 16, 2022.

53 William F. McNeil, The California Winter League: America’s First Integrated Professional Baseball League, (Jefferson: McFarland & Company, 2002), 88.

54 McNeil, The California Winter League: America’s First Integrated Professional Baseball League, 87.

55 Heavy Johnson Game Logs provided by the Seamheads Negro League Database, July 24, 2022.

56 Dixon, Wilber “Bullet” Rogan and the Kansas City Monarchs, 52.

57 Heavy Johnson Game Logs provided by the Seamheads Negro League Database, July 24, 2022.

58 Phil S. Dixon [@NegroLeagueMan], “July 31, 1923, Oscar “Heavy” Johnson became the first Monarch to hit a home run at Kansas City’s Muehlebach Field with a first inning blast off American Giants’ Jack Marshall.” Twitter, July 31, 2018, https://twitter.com/negroleagueman/status/1024481195961270283.

59 Missouri, U.S., Marriage Records, 1805-2002. Ancestry, https://www.ancestry.com/sharing/29954889?h=5f94a8.

60 Baseball-Reference.com, accessed August 16, 2022.

61 Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues, 441.

62 Larry Lester, Baseball’s First Colored World Series: The 1924 Meeting of the Hilldale Giants and Kansas City Monarchs, (Jefferson: McFarland & Company, 2014), 162.

63 “Monarchs, And Sox in Big Trade,” Pittsburgh Courier, March 14, 1925.

64 Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues, 441.

65 “Cleveland Tigers (Baseball),” Encyclopedia of Cleveland History, Case Western Reserve University, https://case.edu/ech/articles/c/cleveland-tigers-baseball, accessed August 15, 2022.

66 “Cleveland Tigers Release,” Birmingham Reporter, June 9, 1928.

67 “Marcos Beat Foe Twice; Lose One,” Pittsburgh Courier, July 4, 1931.

68 “New League Follows Trail of Old,” New York Age, May 21, 1932.

69 Baseball-Reference.com, accessed August 15, 2022.

70 Revel and Munoz, “Forgotten Heroes: Oscar “Heavy” Johnson.”

71 1940 United States Federal Census. Ancestry, https://www.ancestry.com/sharing/29955112?h=478d39.

72 U.S., World War II Draft Registration Cards, 1942. Ancestry, https://www.ancestry.com/sharing/29955369?h=75a9ab.

73 1950 United States Federal Census. Ancestry, https://www.ancestry.com/sharing/29955205?h=967ef6.

74 Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues, 441.

75 Baseball-Reference.com, accessed August 15, 2022.

76 Mark Schremmer, “Ks. Hall inducts Topeka’s Negro League greats,” Topeka Capital Journal, https://www.cjonline.com/story/sports/2012/02/04/ks-hall-inducts-topekas-negro-league-greats/16443539007, accessed August 16, 2022.

77 Laura Spencer [@lauraspencer], “Oscar “Heavy” Johnson mural in @atchisonks. @NLBMuseumKC @nlbmprez” Twitter, July 16, 2022, https://twitter.com/lauraspencer/status/1548332326244868096.

78 Baseball-Reference.com, accessed August 16, 2022.

Full Name

Oscar Johnson

Born

April 20, 1895 at Atchison, KS (USA)

Died

October 9, 1960 at Cleveland, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.